Opinion: Mars rocks are a science prize the U.S. can’t afford to lose

- Share via

NASA does difficult, inspiring and ambitious things — and it does them, in the immortal words of President Kennedy, because they are hard. NASA’s most ambitious planetary project yet is Mars Sample Return, a partnership with the European Space Agency to robotically collect and bring back to Earth scientifically invaluable rocks from Mars for study in labs here. But the mission is in trouble.

Mars Sample Return represents the culmination of decades of planning by the planetary science community, and it has been the top-ranked scientific priority of the last two Decadal Surveys of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The surveys are exhaustive reports written by dozens of scientists over many months, designed to help NASA chart its agenda in 10-year increments.

There are compelling reasons to bring samples back from Mars.

With a final 2024 budget for NASA in place, the space agency has directed JPL not to cut any more staff working on the Mars Sample Return mission.

The technologies required for retrieving soil and rocks from Mars will underpin those needed for NASA’s Moon to Mars initiative, a grand plan to eventually send humans to Mars and bring them safely home. And successfully retrieving study samples from Mars would reaffirm the United States’ leadership in robotic space exploration at a time when China is eyeing that very same prize.

The samples have the potential to revolutionize our understanding of the Red Planet’s geological history and whether it might ever have hosted life. They will offer vital information about the environment Mars astronauts would encounter, and they will give us brand-new insight into the processes that shape planets generally. Just as scientists have done with 50-year-old Apollo moon samples, what is collected now can be studied for decades to come, making use of analytical capabilities yet to be invented and representing a scientific gift that keeps on giving.

Perseverance, NASA’s newest Mars rover, is living up to its name. It has already survived a hurdle no previous rover has had to face: a global pandemic.

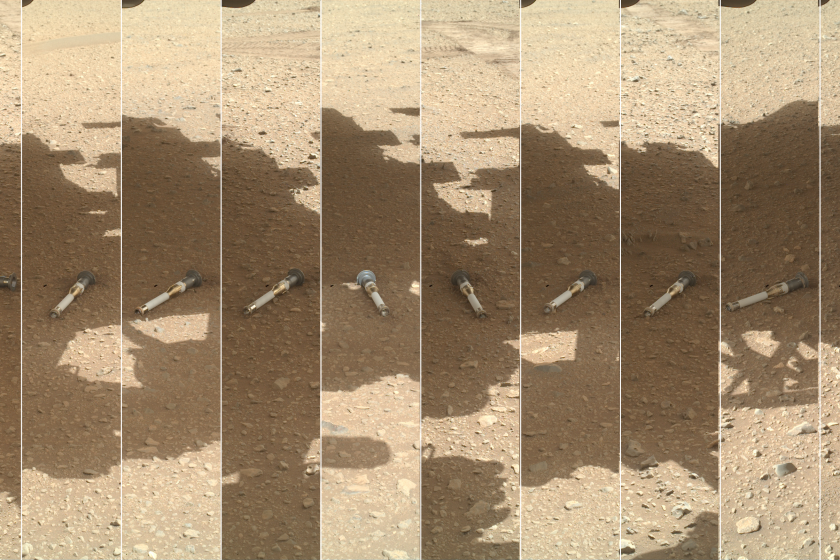

The first phase of Mars Sample Return has already begun. In February 2021, the rover Perseverance landed on Mars tasked with collecting air, rock cores and soil that would ultimately be returned to Earth. Equipped with a sophisticated sampling system, Perseverance has already filled 23 of its collection tubes and has 15 more.

The envisioned next phase is sending a Sample Retrieval Lander to rendezvous with Perseverance, transfering the samples and then launching them into space, to be picked up by an Earth Return Orbiter furnished by ESA.

Yet how, when, or even if those next phases will happen is far from certain.

Faced with rising costs, NASA commissioned an independent review of the entire program in 2023. The review didn’t pull punches, finding that the likely cost of the project had ballooned, its organizational structure wasn’t working, and that NASA hadn’t effectively communicated to the science community or the public why the massive effort was worthwhile in the first place. Despite that, the review emphasized that the scientific and geopolitical value of Mars Sample Return couldn’t be overstated, and that the project could be made affordable.

A hiring freeze wasn’t enough to avoid layoffs after NASA ordered cuts to the MSR mission. Some 530 employees and 40 contractors will lose their jobs.

Still, the Senate threatened to reduce the project’s budget substantially and even cancel it outright, which starkly contrasted with the House’s proposal to support the program fully. Congress now proposes to fund it at some level, but this uncertainty has driven NASA to “ramp back” its Mars Sample Return-related activities. As a result, Pasadena’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, NASA’s lead center for the project, laid off more than 600 staff members last month — highly skilled expertise that NASA can no longer access.

Now Congress has a choice: It can turn its back on Mars Sample Return or commit to funding the boldest robotic planetary science effort humanity has yet undertaken.

The sample project must be put on a financially affordable path as part of NASA’s overall program of U.S. planetary exploration — returning samples from Mars cannot happen at the expense of every other planetary science enterprise at the agency. A team began developing a cost-effective path forward last year, in response to the independent review’s criticisms. Its proposals are expected later in March.

But even a streamlined and fiscally sound project of the scale and payoff of the Mars Sample Return will require more money than previous planetary missions. That’s the nature of doing something that’s never been done before.

And let’s be clear: Abandoning the project would not only sacrifice work already underway, it would be a major blow to the Decadal Survey process, hurting not just planetary science but the other science communities that have relied on the survey process for establishing scientific and funding priorities going as far back as the 1960s.

Congress should sufficiently fund NASA to realize the generational goal of returning to Earth samples from Mars. For a fraction of the country’s annual non-defense discretionary spending — or about 5% of what Americans spend on pizza each year — the United States can set its sights on the Red Planet like never before. In doing so, we can answer fundamental questions of planetary science, bolster our relationships with our international partners and inspire the next generation of explorers.

Mars Sample Return is hard, but that isn’t its problem. For NASA, and for the United States, it’s perhaps the single best reason to do it.

Paul Byrne is an associate professor of earth, environmental and planetary science at Washington University in St. Louis. Vicky Hamilton is an institute scientist at Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo. Both have dealings with NASA but are not directly employed by the agency.