Op-Ed: As a Holocaust survivor, the most important thing I can do is share my story

From Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., antisemitism is once again on the rise, being echoed by celebrities with wide audiences such as Kanye West and Kyrie Irving. To Jewish people who remember the Holocaust — or those, like myself, who survived it — this shameless bigotry is nothing new. Although the Holocaust ended more than 75 years ago, these instances point to how hatred toward Jewish people is perpetuated to this day, along with Holocaust denial.

In a certain sense, I can understand the impulse to want to distance oneself from atrocities like the Holocaust that expose an evil side to humanity. In a few instances, I have been confronted by people who are skeptical or in denial that the Holocaust even happened. Though it is difficult to confront those who outright deny my experience, these interactions only underscore the importance of my work.

As a survivor, I have made it my mission to honor the memory of the Jewish people by sharing my story with the world. I have come to view education as one of the most powerful tools we have to prevent violence and foster peace and understanding. Through interviews and speeches over the years, I have given my account of the Holocaust and the ways that antisemitism continues to endanger our society. I have visited schools and libraries and attended many events to tell my story as a Jewish person in World War II.

Recently, I had the honor of speaking at the Reagan Presidential Library as it announced its historic exhibit, “Auschwitz: Not Long Ago. Not Far Away.” For the Holocaust deniers and doubters, this exhibit is a stark reminder that truth cannot be compromised but must be faced head-on and defended in every generation.

I feel fortunate to be a voice for the millions of voiceless victims who were killed by the Nazi regime. But it is not only my duty — it is the duty of every one of us to keep the memory of the Holocaust alive in the face of an apathetic world.

The Nazi regime killed more than 6 million people. The regime sowed hatred among the German and European people and thrived by making our differences into dangers and inferiorities. During the war, close to 100 of my family members were among the Jewish people who lost their lives in the Nazi concentration camps. My mother and brother were just two of many.

After living for years in the Lodz Ghetto, a region in Poland established by Nazis where Jewish people were exploited for their labor, I was sent in 1944 to Auschwitz, where I survived the remainder of the war. After the war ended, I began to rebuild my life, first in Sweden, and then eventually in the United States.

At the start of the war, Germany was considered an enlightened country. Germans had long been at the forefront of culture, art, music and philosophy. Still, Nazism rose and festered throughout German society, culminating in genocide. In the United States today, we are not yet facing the climate of Germany in those prewar years, but it’s important that we remain vigilant against the rise in antisemitism before it takes off. According to the Anti-Defamation League, there have been more than 1,500 antisemitic incidents in the U.S. this year alone. We must not grow complacent and desensitized to these acts of hatred.

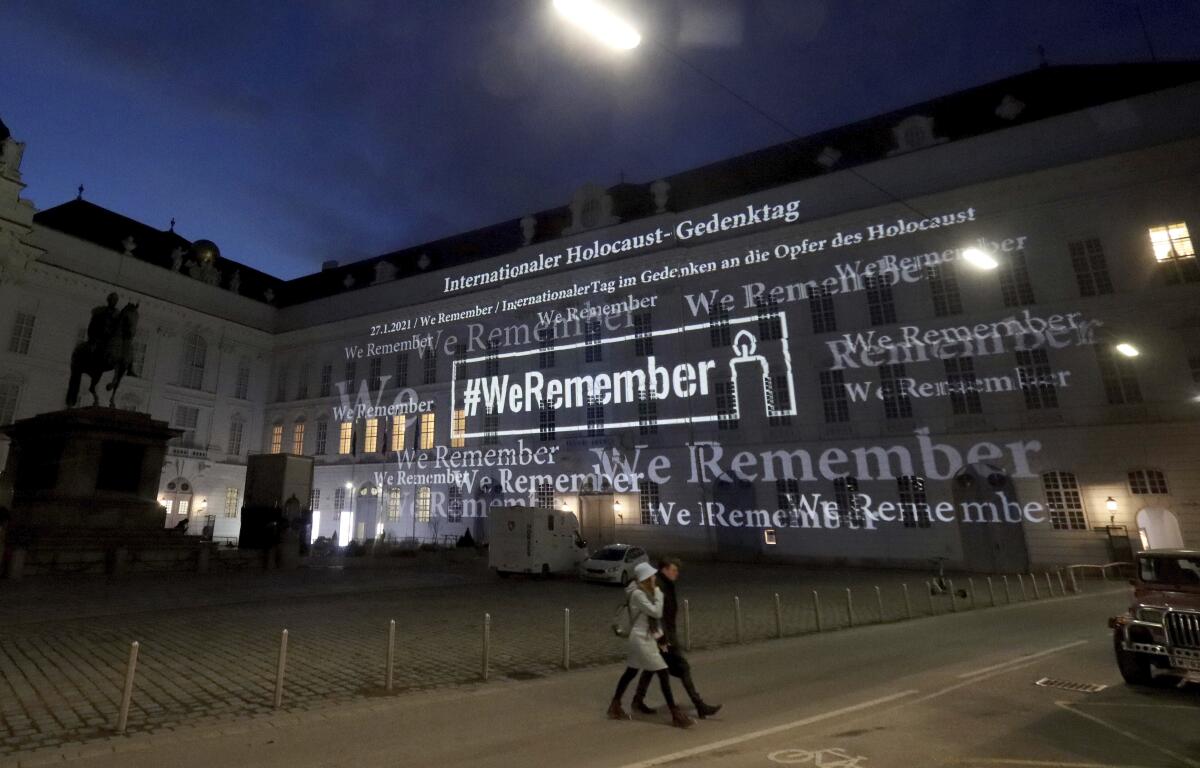

We owe it to Holocaust victims, those who lost their lives and those who survived, to remember them. Scholars have said that “the final act of genocide is the denial of genocide.” We must acknowledge the horror they endured lest we deny them their humanity once again.

The Jewish people will never get back all they lost during the Nazi regime, but the world owes it to them to continue to speak and listen, to teach and learn, to ensure that our suffering will never be forgotten.

As the number of Holocaust survivors and citizens of the world who lived through World War II dwindles, it is through stories, objects and memories that the Jewish people’s legacy lives on. Survivors like me need to know that our experiences have meaning and that our community cares about what becomes of us. To make sure atrocities such as the Holocaust never happen again, we need to keep these stories alive.

David Lenga, 95, is an Auschwitz survivor. He lives in Woodland Hills.