Editorial: Congress wants to make health insurance more affordable — but only for some, and only temporarily

- Share via

One of the many lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic is that a health insurance system that relies on employer-sponsored policies is poorly equipped to handle a disease-induced recession. Millions of Americans lost their coverage when the economy plunged, taking their jobs (and badly needed health benefits) with it.

Fortunately, Americans under 65 had a double-layered safety net: Medicaid to cover people with little or no income, and the state Obamacare exchanges to offer private insurance policies to the rest of the uninsured. The 2010 Affordable Care Act created the exchanges to serve people not eligible for coverage by a large group health plan, with income-based subsidies for Americans earning up to four times the federal poverty level.

For people who were still earning more than a minimal amount of money, however, the coverage could be costly even with subsidies. Premiums were capped at almost 10% of household income for people earning three to four times the federal poverty level, and there was no cap for people with higher incomes. Combined with steadily rising deductibles, high premiums have been one of the biggest challenges not just for the ACA but for the entire U.S. healthcare system.

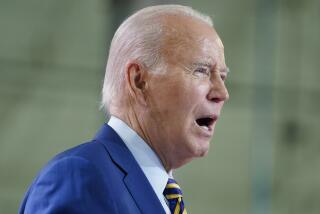

This week, Congress is expected to take a major step toward easing the costs of Obamacare plans. The version of President Biden’s $1.9-trillion COVID relief bill that lawmakers are poised to approve includes larger premium subsidies for ACA policies, lowering the percentage of income that anyone would have to spend on insurance through 2022. Even people earning more than four times the poverty level will pay no more than 8.5% of their income for coverage this year and next year.

That’s a big (albeit temporary) improvement in affordability, especially for working-class Americans with moderate incomes. In California, for example, the average savings could be $100 a month for people earning less than four times the poverty level, said Peter V. Lee, executive director of Covered California. But it’s not cheap — the Congressional Budget Office estimated that the extra subsidies will cost taxpayers about $34 billion.

The challenge for Congress will be to find a permanent solution to the affordability problem, and not just for people enrolled in the ACA. Treatment costs have been growing faster than inflation for years, and though the ACA experimented with ways to give doctors and hospitals more incentive to limit spending, the industry remains on an unsustainable path.

Higher subsidies are a straightforward response to the growing costs, but they’re the equivalent of a pill that treats the symptoms without curing the disease. Actually restraining the growth of healthcare spending — reducing unnecessary procedures and getting more value out of every dollar spent — is hard and controversial work. Biden’s relief bill buys lawmakers a little time, but they need to get cracking.