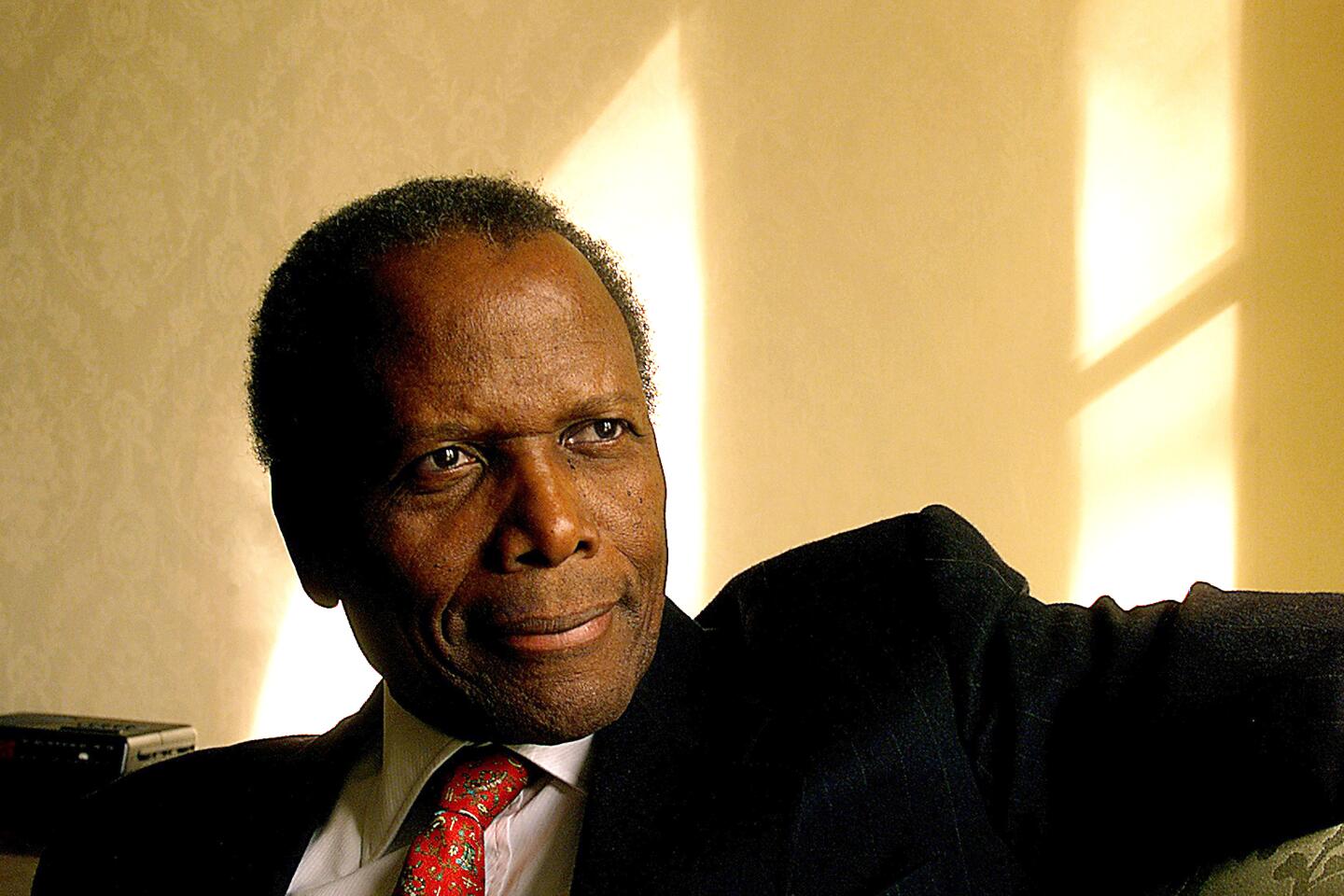

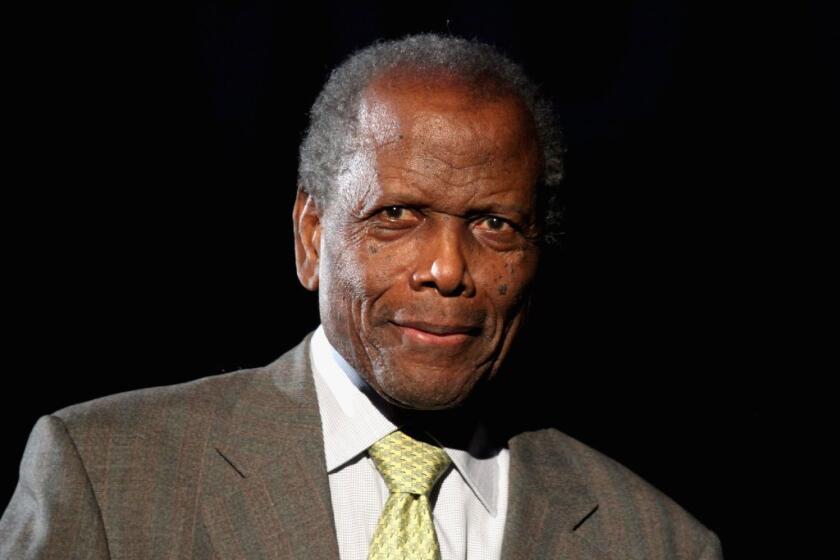

Sidney Poitier, trailblazing star who helped break down Hollywood color barriers, dies at 94

Sidney Poitier, who made history as the first Black man to win the Oscar for lead actor and starred in “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” has died.

- Share via

It was the most unlikely of beginnings. Newly arrived from the Bahamas with a thick West Indian accent, Sidney Poitier fumbled his lines so badly when he tried out for the American Negro Theatre in Harlem that he was advised he’d be better off getting a job as a dishwasher.

Humiliated but unbroken, Poitier bought a $13 radio and spent hours listening to the announcers, mimicking their pronunciation and the rhythms of their speech. When he returned to the theater, his audition was little better, but when another unknown actor, Harry Belafonte, pulled out of a performance, Poitier stepped into the limelight.

His ascent was meteoric, smashing through the Hollywood color barriers during a time when Black people on the Hollywood studio lots were generally kitchen workers and janitors. On film they were often cast in singing and dancing roles, footage that could easily be snipped when the movies rolled out in the Deep South.

At the height of the civil rights movement as the nation heaved with racial tension, Poitier arose as one of the top box-office draws of the 1960s in films such as “In the Heat of the Night” and “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” cementing it all as he became the first Black performer to win an Academy Award for lead actor.

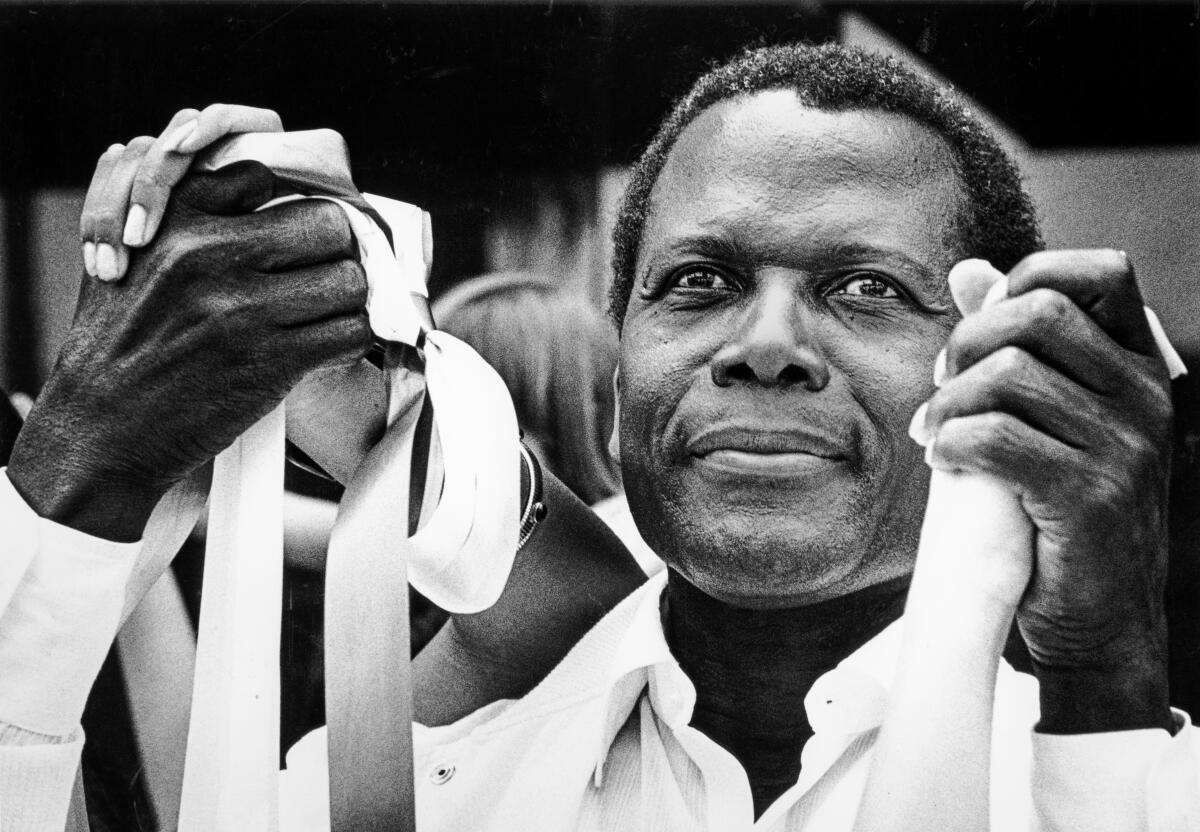

A towering role model for succeeding generations of Black actors, Poitier died Thursday at his home in Los Angeles, Latrae Rahming, the director of communications for the prime minister of Bahamas, told the Associated Press. He was 94.

“This is a big one. No words can describe how your work radically shifted my life,” actress Viola Davis wrote on Instagram. “The dignity, normalcy, strength, excellence and sheer electricity you brought to your roles showed us that we, as Black folks, mattered!!!”

Former President Obama said Poitier opened doors that had long been firmly closed to Black Americans. “Sidney Poitier epitomized dignity and grace, revealing the power of movies to bring us closer together,” Obama wrote on Twitter.

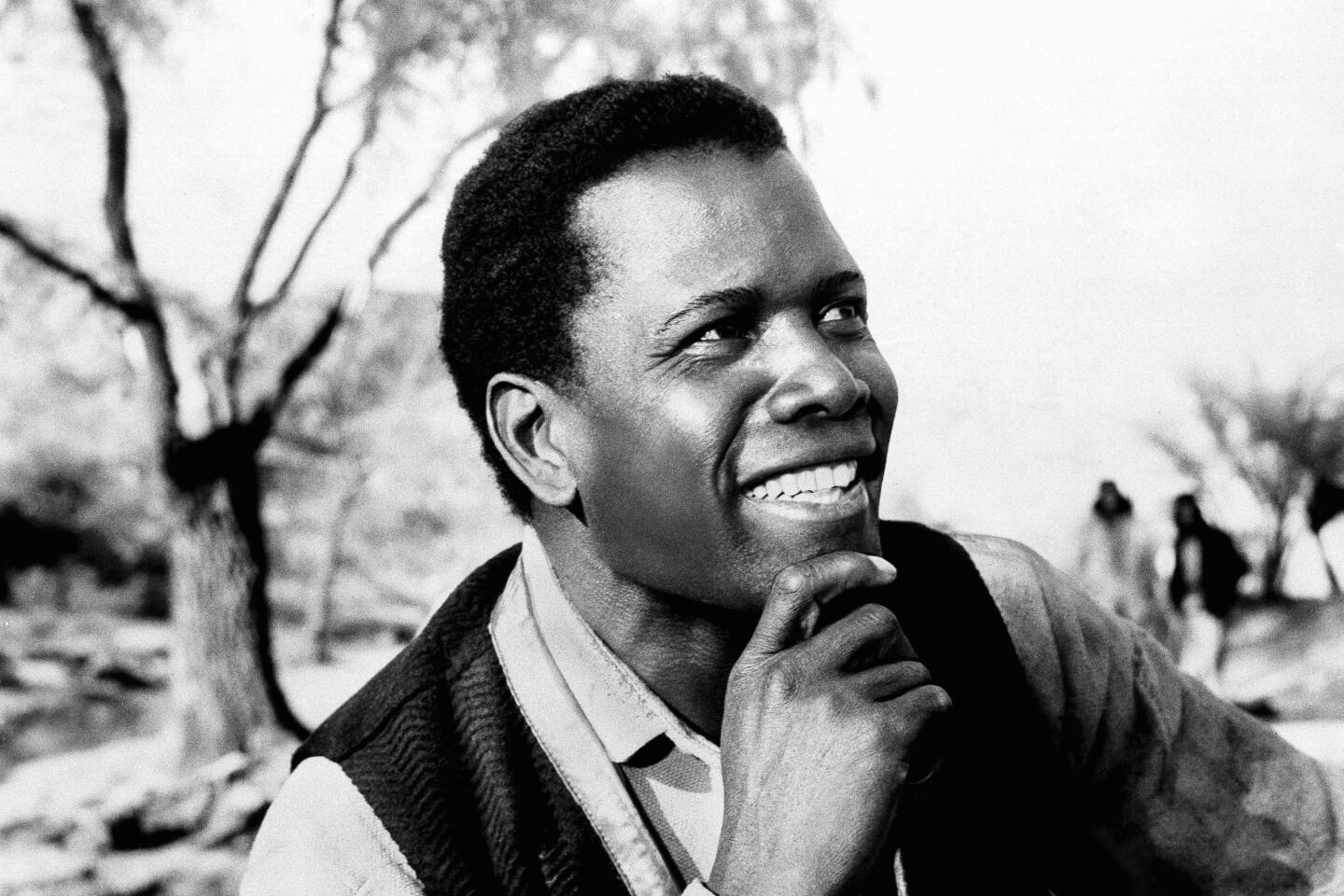

Tall and handsome, with a low and seductively smooth voice and what one writer called an “almost princely bearing,” Poitier projected an air of quiet dignity in roles that shattered stereotypes.

“He’s a major figure in American history because he truly represents the complete breakthrough of the Black American actor into stardom,” Jeanine Basinger, founder of the film studies program at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Conn., once told The Times.

Basinger said Poitier “had everything it took” to be the screen’s breakthrough Black actor.

Actor James Earl Jones agreed: “When he became a star, everyone, white and Black, said, ‘I like this man.’“

Poitier made his feature film debut in 1950 playing a young intern in a county hospital prison ward in “No Way Out,” director Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s explosive look at racial prejudice starring Richard Widmark.

Poitier began his film career at a time when roles for Black actors were few and far between. But it also was a time when Hollywood studios were increasingly willing to deal with controversial and sensitive subjects.

Racial stereotyping in the movies was still in full force when Poitier appeared in “No Way Out.” But, as former Los Angeles Times arts editor Charles Champlin wrote decades later, the film “reflected the stirrings toward more significant roles ... and better representations of the Black experience in American society.”

Indeed, although he initially experienced a lean period, Poitier appeared in 15 films over the next dozen years, including “Cry, the Beloved Country,” “Blackboard Jungle,” “Edge of the City,” “The Defiant Ones” and “A Raisin in the Sun.”

The 1961 “Raisin” saw Poitier reprise his role as the mercurial Walter Lee Younger in the film of Lorraine Hansberry’s groundbreaking 1959 Broadway play about a Black family.

Stanley Kramer’s 1958 film drama “The Defiant Ones,” in which Poitier and Tony Curtis starred as escaped convicts who are shackled together, was a breakthrough role for Poitier, earning him an Oscar nomination for lead actor — a first for a Black performer.

But it was his Oscar-winning starring role in “Lilies of the Field,” a low-budget, black-and-white film directed by Ralph Nelson, that provided the high-profile next step in propelling him to superstar status. “Song of the South” actor James Baskett had been given an honorary Academy Award in 1948, but Poitier became the first Black man to win the Oscar for lead actor.

As Homer Smith, Poitier played an ex-GI drifter who meets five refugee nuns from East Germany after his station wagon overheats in the Arizona desert, and he is talked into building a chapel for them. A high point of the film comes when Poitier leads the nuns in singing the Baptist spiritual “Amen.”

At the peak of his popularity, in 1967, Poitier starred in three of the highest-grossing movies of the year: “In the Heat of the Night,” “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” and “To Sir, With Love.”

In 1968, according to a poll of movie exhibitors, Poitier was the No. 1 box-office star of the year.

Sidney Poitier still delivers ‘Heat’

Director Norman Jewison’s “In the Heat of the Night,” in which Poitier played a smart and sophisticated Philadelphia police homicide detective who is pulled into a murder investigation in a small town in Mississippi, provided the actor with two of his most memorable onscreen moments.

In one, Rod Steiger, in his Oscar-winning role as the redneck police chief, used a racial slur while saying that “Virgil is a funny name” for a Black man from Philadelphia. Then he asks, “What do they call you up there?”

With steely eyes, Poitier responds with the line that became his signature: “They call me Mr. Tibbs.”

The racially charged crime drama’s other memorable moment came in the greenhouse of the town’s most influential citizen, a racist cotton plantation owner played by Larry Gates: When the wealthy white man realizes that the Black police detective is there to question him about the murder, he slaps Poitier’s Tibbs in the face.

Without hesitation, Tibbs gives the white man a backhanded slap in return.

It is, said Basinger, “a defining moment in film. It’s like, ‘Times have changed, buster; I’m the hero, not you.’ It was great and done with great dignity.”

What is canon in American film history? Maya Cade’s Black Film Archive sets out add ignored Black titles.

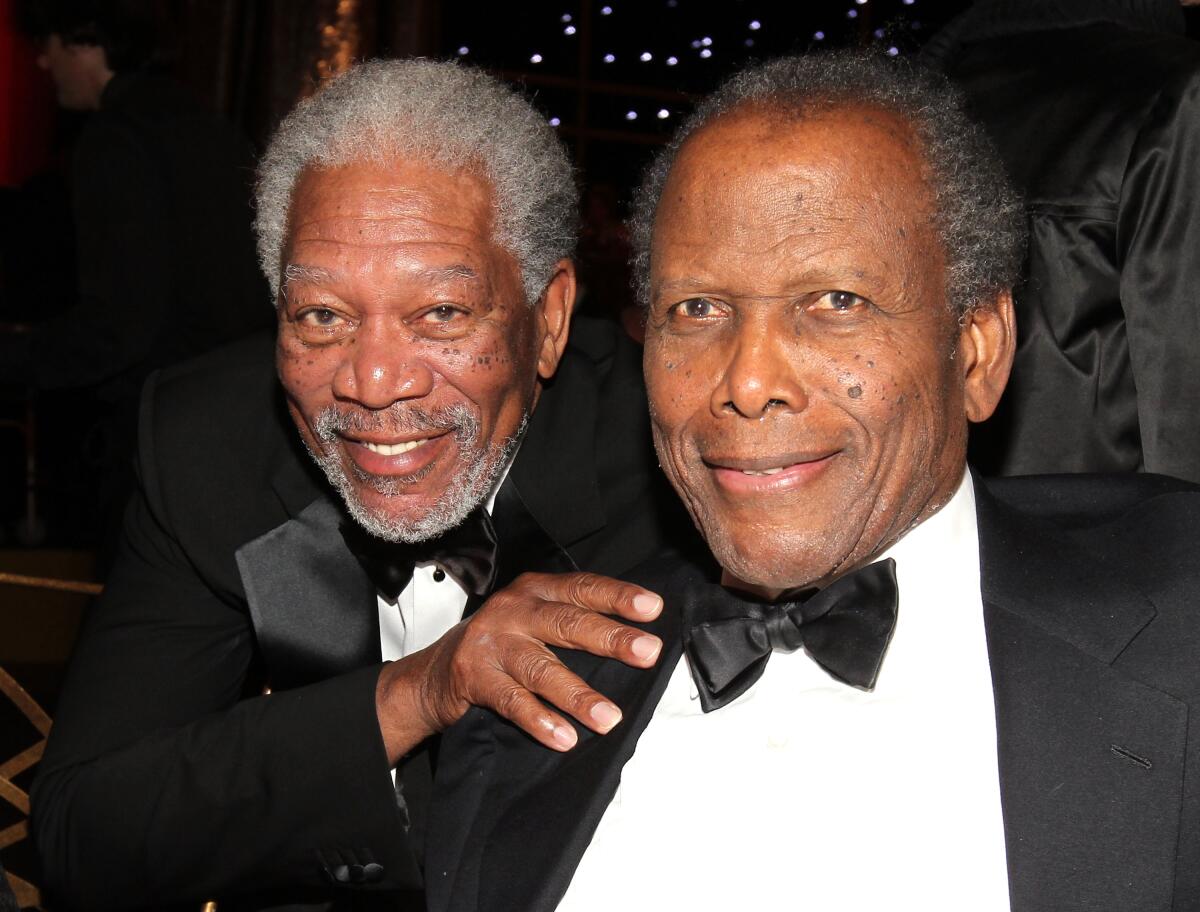

Poitier’s success inspired legions of Black actors over the years, including Danny Glover, who once told Poitier, “You have made it possible for me to dream bigger dreams.”

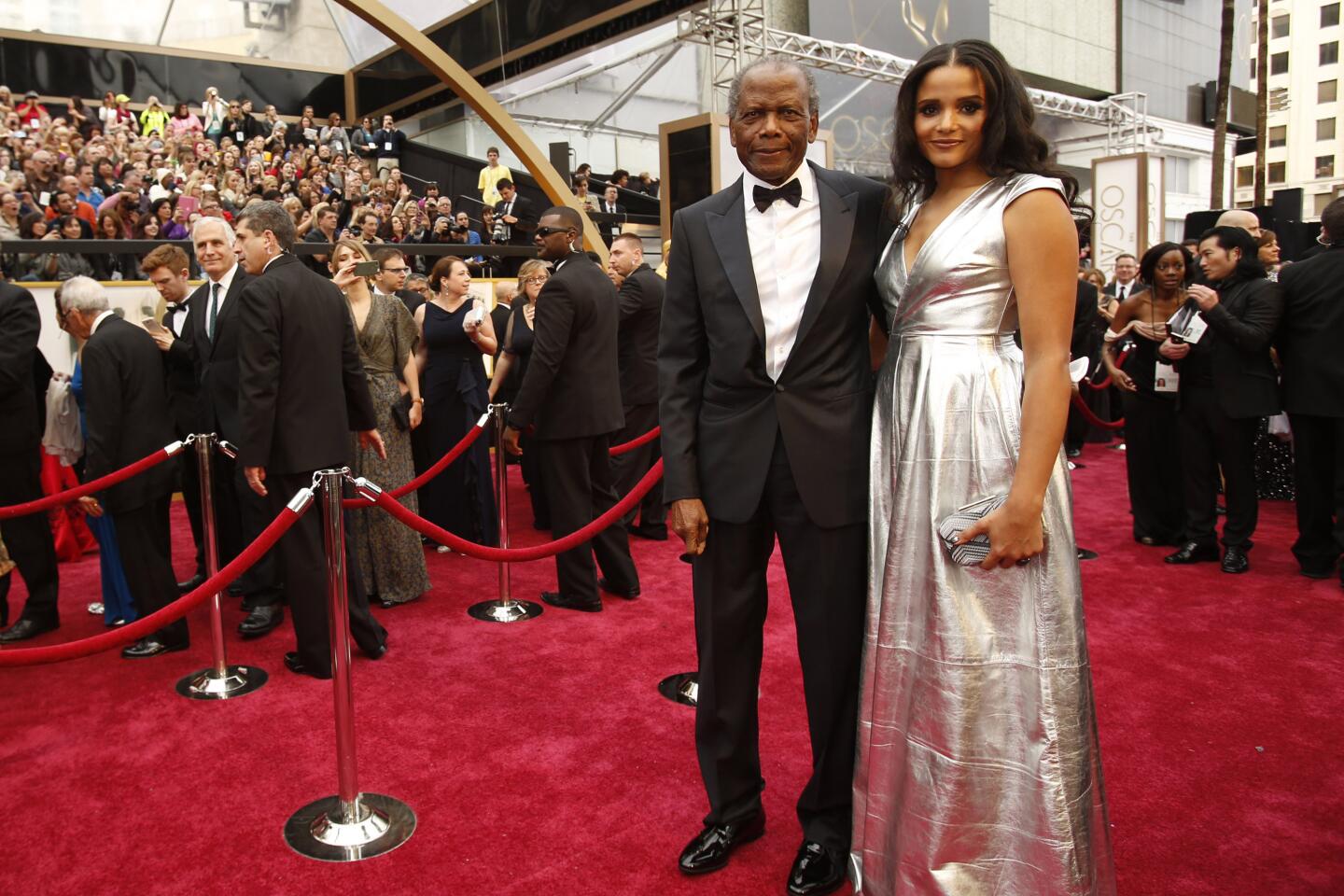

Denzel Washington called Poitier a source of pride for Black Americans. He acknowledged him onstage at the Academy Awards in 2002, when Washington became the first Black performer to win the lead actor Oscar since Poitier.

“For 40 years I’ve been chasing Sidney,” Washington said. “I’ll always be following him. There’s nothing I’d rather do.”

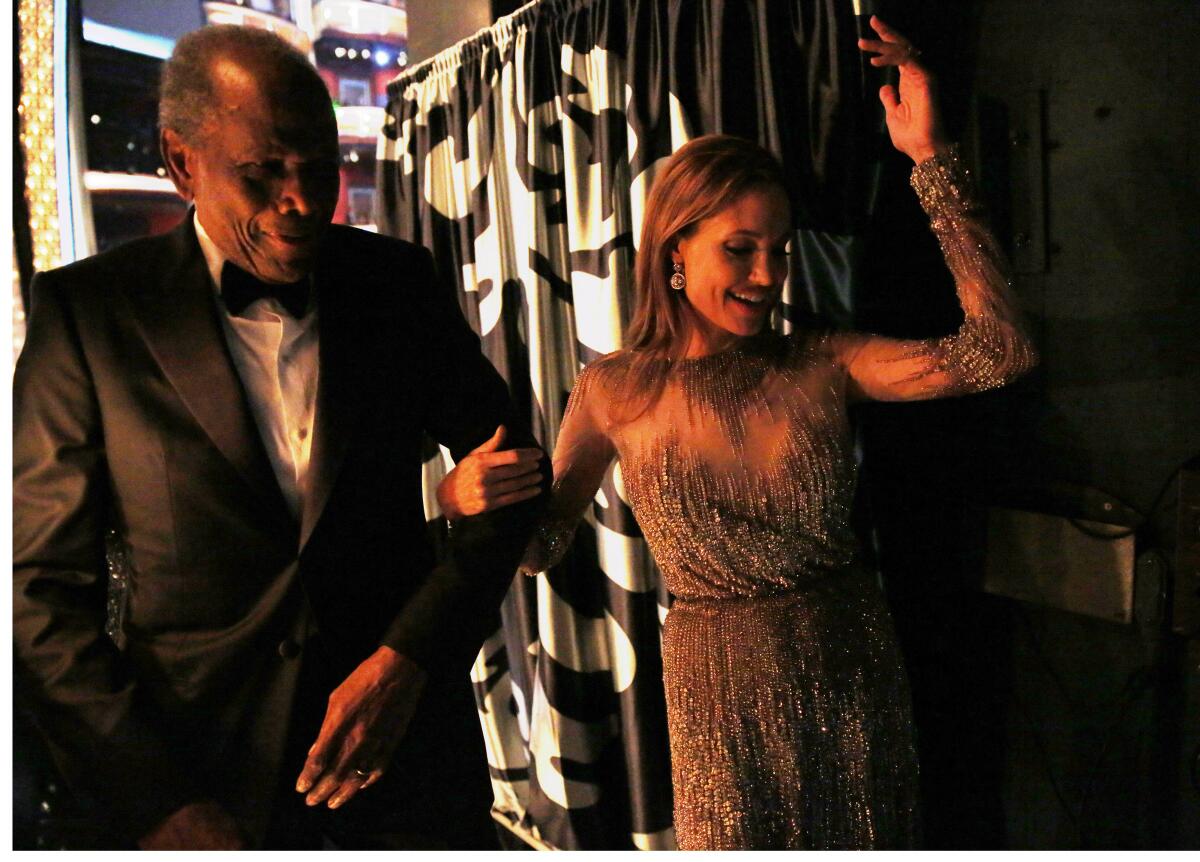

The same night Washington received his Academy Award — and Halle Berry became the first Black woman to win the lead actress Oscar — Poitier received an honorary Oscar for his five-decade career.

“I accept this award,” Poitier said in his acceptance speech, “in memory of all the African American actors who went before me in the difficult years and on whose shoulders I was privileged to stand to see where I might go.”

Poitier was born Feb. 20, 1927, in Miami, making him an American citizen purely by chance: His parents, Bahamian tomato farmers, were visiting Miami to sell their tomatoes at the Produce Exchange.

The last of his parents’ seven surviving children, Poitier grew up on Cat Island in the Bahamas, an impoverished, 45-mile-long narrow strip of land with no plumbing or electricity, few jobs and little schooling.

After the U.S. government placed an embargo on the importation of tomatoes from the Bahamas and the island’s tomato farmers succumbed to the economic disaster, the Poitiers moved to Nassau, the capital of the islands.

At 13, after only a year and a half of formal education, Poitier dropped out of school and worked briefly as a water boy for ditch diggers and later as a laborer in a warehouse.

Two years later, in 1943, he and some friends were jailed overnight for stealing ears of corn, and his father, worried his son might get into deeper trouble, sent him to live with his older brother, Cyril, in Miami.

There, he worked as a delivery boy and parked cars and, for the first time, encountered institutionalized racism. To escape the racism of the Deep South, he headed north, to New York City.

Sidney Poitier’s roles as a historical marker

Arriving alone with less than $4 in his pocket, the 16-year-old Poitier slept in pay-toilet cubicles and on the roof of the Brill Building before landing a job as a relief dishwasher in restaurants and moving into a $5-a-week-room in Harlem.

After a stint in the Army — he had lied about his age to get in, saying he was 18 rather than 16 — he returned to Harlem upon his discharge in late 1944 and resumed working as a dishwasher.

One day, while scouring the want ads in the Amsterdam News, a Black newspaper, he saw an advertisement: “Actors Wanted by Little Theatre Group.” It was an ad for the American Negro Theatre.

At his audition at the theater, Poitier recalled in a 1992 interview with The Times, he was handed a script and told to read one of the parts. But with only a year and a half of formal education, he read haltingly and with a thick West Indian accent.

As Frederick O’Neal, one of the founders of the theater, came up onstage and physically marched Poitier to the door, he angrily told him to stop wasting people’s time and added, “Why don’t you get yourself a job as a dishwasher or something?”

Poitier was shaken by the comment and remembered thinking, “Was there a mark on me that my destiny is that of a dishwasher?”

Defiantly determined to become an actor, if only to prove to O’Neal that he could be more than a dishwasher, Poitier worked on his enunciation while listening to his cheap radio and reading the city’s many newspapers aloud.

Perhaps the best way to throw a successful black-tie award gala is to have entertainment so dazzling that midway through the evening, it’s forgotten that nights like this are by tradition terminally boring.

Six months later, Poitier returned to the American Negro Theatre to audition for a new class of actors.

Despite another poor audition, he was accepted on a three-month trial basis — an arrangement that was extended when he made a deal to serve as the theater’s janitor in return for acting lessons.

After nine months of training, Poitier became the understudy to Belafonte, as the lead in the annual student production.

At rehearsal one night, Poitier had to step in for Belafonte. A Broadway producer who had stopped by was so impressed by Poitier’s performance that he cast him in a small role in an all-Black version of the Greek comedy “Lysistrata” on Broadway.

The 1946 play closed after only four performances. But despite fumbling his lines on opening night, Poitier won praise from several reviewers.

That led to his being hired as an understudy in the road company of the hit Broadway show “Anna Lucasta,” a play about a Polish family that had been transformed into a story about a Black family.

Then, in 1949, came the 22-year-old Poitier’s first big break — a screen test for his role as the young intern in “No Way Out.”

During the height of his career in the late 1960s, Poitier faced criticism from Black militants and others who labeled him “a showcase Negro” and “the white man’s Black man.”

Poitier also was aware of the “hostility” some fellow Black actors had against him over the many professional opportunities he had received.

“I can tell you what I think the flak was about,” he told the Washington Post in 1995. “For a long time, I got all the jobs — one picture after another after another. And the roles I played were very unlike the average Black person in America at the time.

“The guy always had a suit, a tie, a briefcase. He was a doctor, lawyer, police detective. Middle class. The characters weren’t reflective of the diversity of Black life. I don’t know that I wouldn’t have had resentments myself, had I been an actor on the outside looking in.”

Nevertheless, he said, “I was at peace with the fact that what I was doing was compatible with the social revolution across the country. I’ve never done an acting job that I was ashamed of.”

It’s early morning at the Polo Lounge in Beverly Hills and all eyes in the crowded restaurant are glancing over at Sidney Poitier.

Over the years, Poitier told the Washington Post in 1997, he tried to choose roles “with great care, to use the talent I had to the very best ends. Because I knew how many hopes and dreams were riding on how I portrayed myself, in my characters.”

Beginning in the early 1970s, a period that gave rise to blaxploitation films such as “Shaft” and “Superfly,” Poitier was increasingly absent from the screen.

After reprising his “In the Heat of the Night” detective in two sequels, “They Call Me Mister Tibbs!” and “The Organization,” Poitier launched a new phase of his career as a director, beginning with the 1972 western “Buck and the Preacher,” in which he co-starred with longtime friend Belafonte.

Poitier directed eight more films over the next 18 years, including two popular comedies in which he co-starred with Bill Cosby, “Uptown Saturday Night” and “Let’s Do It Again,” and the Gene Wilder-Richard Pryor comedy hit “Stir Crazy.” He also played an FBI agent in two films, “Shoot to Kill” and “Little Nikita.”

On Thursday night, at festivities to be televised later, Sidney Poitier will become the American Film Institute’s 20th Life Achievement Award winner (a succession that began with John Ford in 1973 and has included James Cagney, Orson Welles, Bette Davis and Alfred Hitchcock, among others).

He resurfaced in the 1990s, mostly in TV movies, notably “Separate but Equal” and “Mandela and de Klerk.”

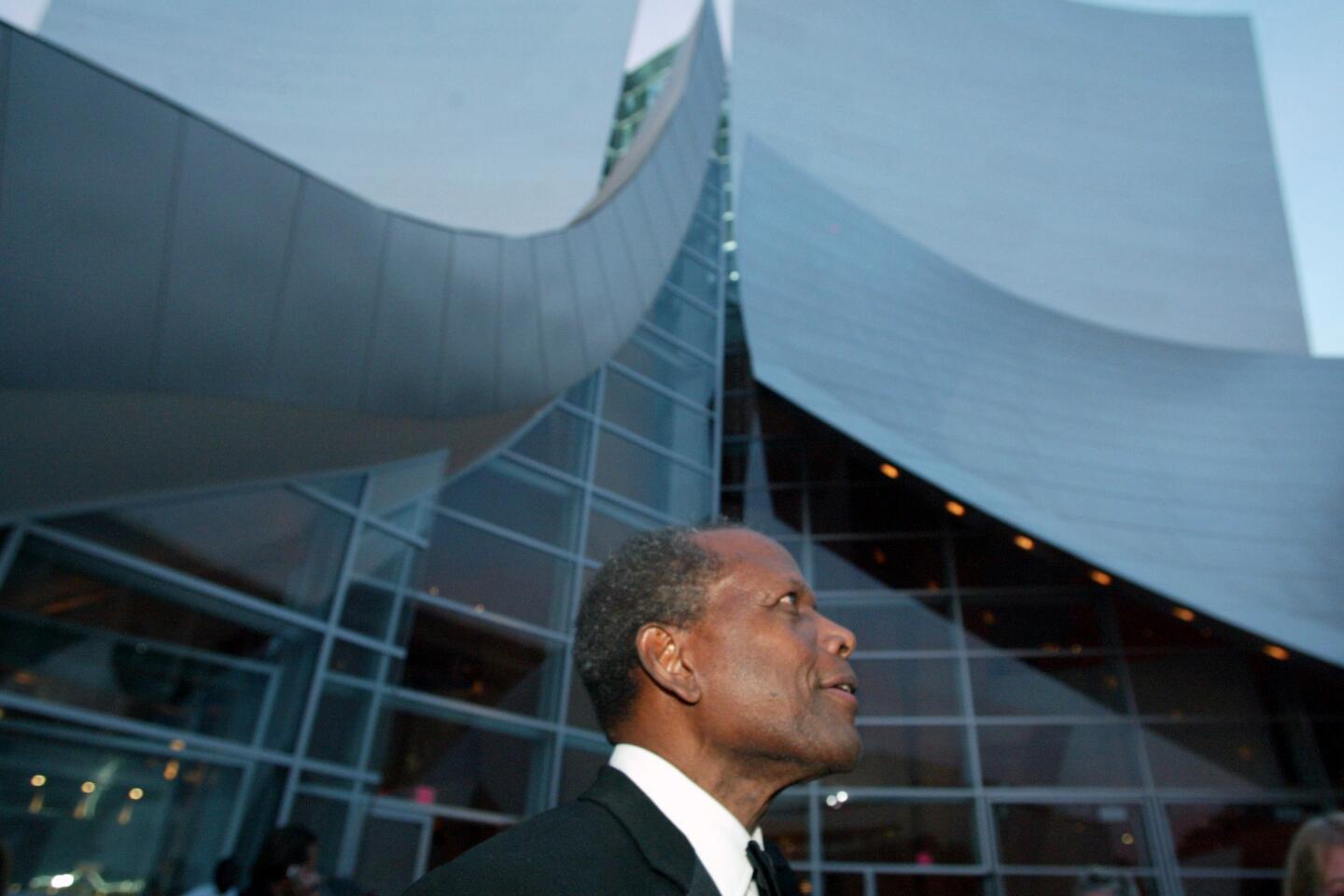

In 1992, Poitier became the first Black person to receive the American Film Institute’s Life Achievement Award. Three years later, he received a Kennedy Center Honor.

Poitier, who was active in the civil rights movement in the 1960s and marched with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., also received the NAACP’s Hall of Fame Award for his depiction of positive screen images and a lifetime achievement award from the Screen Actors Guild.

In 1997, Poitier, who had dual American-Bahamian citizenship, was appointed as the Bahamian ambassador to Japan. When Hurricane Dorian hit the Bahamas in September 2019, Poitier said he had 23 relatives who went missing.

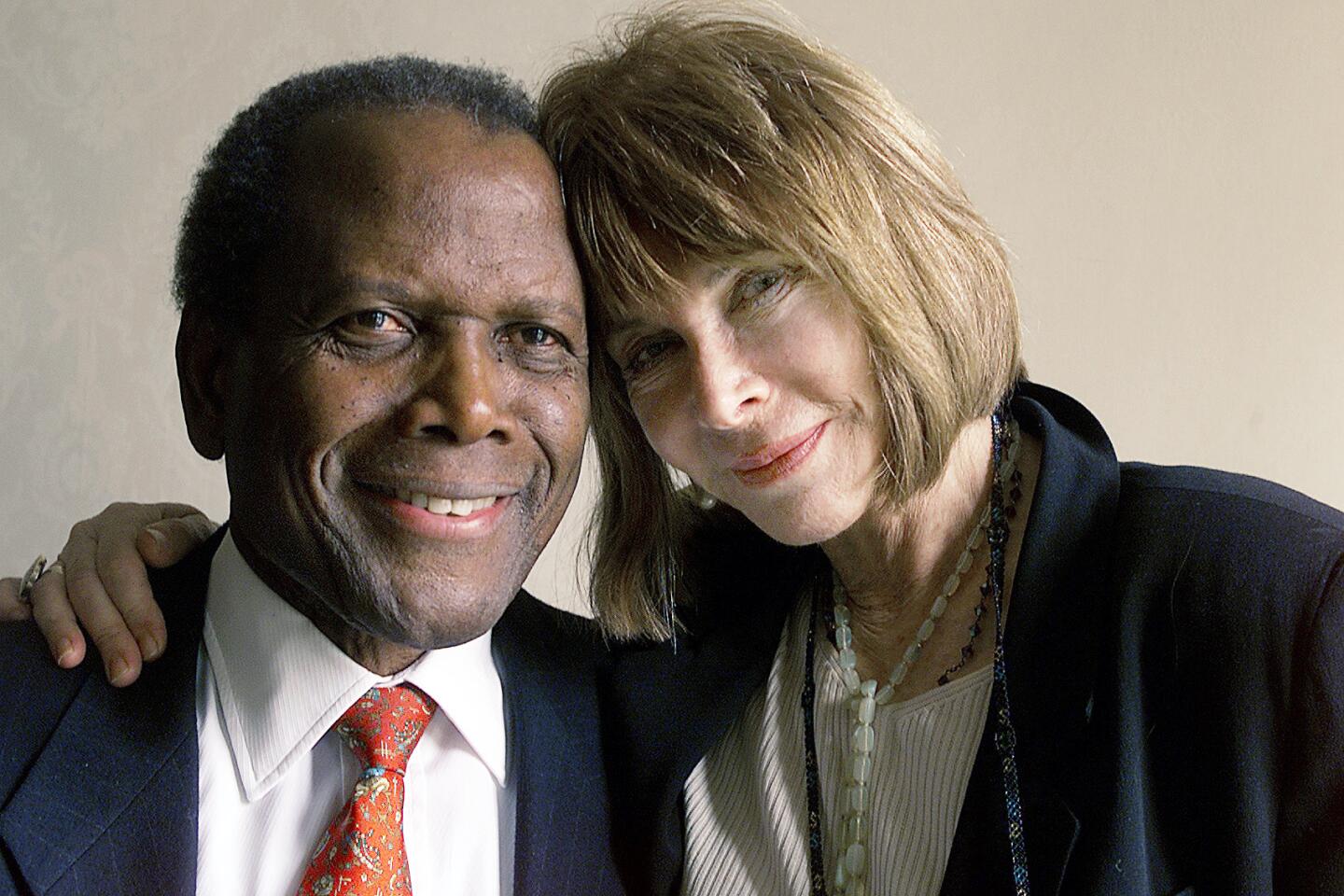

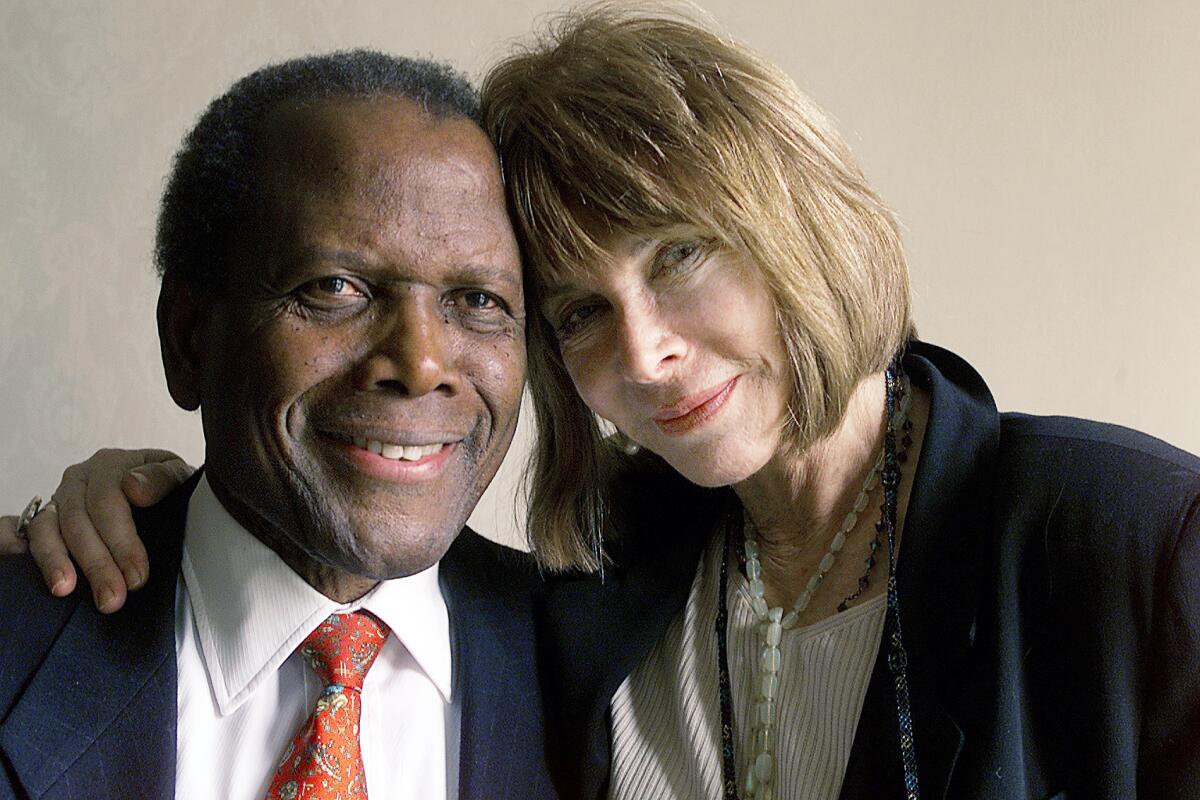

Poitier‘s first marriage, to model-dancer Juanita Hardy, with whom he had four daughters, ended in divorce in the mid-1960s. In 1976, he married Canadian-born actress-model Joanna Shimkus, with whom he had two daughters.

Dennis McLellan is a former Times staff writer.