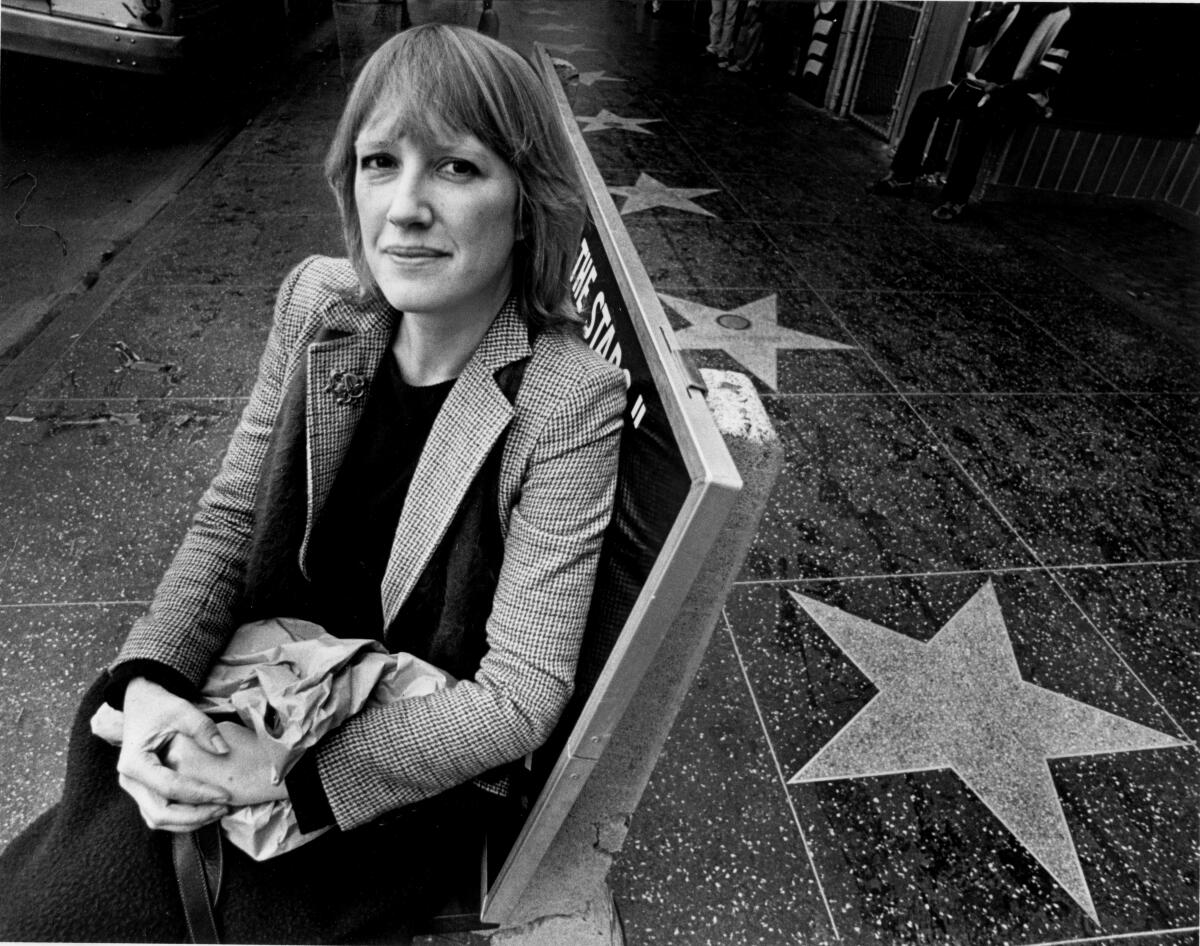

Author Eve Babitz, who captured and embodied the culture of Los Angeles, dies at 78

Eve Babitz, the author known for her hedonistic chronicles of Los Angeles drawn largely from her own life, died Friday at 78.

According to her sister, Mirandi Babitz, the cause of death was complications from Huntington’s disease. Babitz, who after living for many years in West Hollywood had most recently been in a Westwood assisted-living facility, died at UCLA Medical Center.

Babitz’s books wove back and forth between fiction and nonfiction, but all of it was rooted in her own experiences. Her books included “Eve’s Hollywood,” “Slow Days, Fast Company,” “Sex and Rage,” “Black Swans” and the collection “I Used to Be Charming,” published in 2019.

Her writing described a world of decadent glamour with fine-tuned detail but also a sense of open-hearted joy, often shared with the dishy candor of a close friend deep into a soggy late-afternoon lunch. The outsize details of Babitz’s own life — among her known former lovers are Jim Morrison, Ed Ruscha, Harrison Ford and Steve Martin — at times threatened to draw focus from her work.

The title essay of the last collection covers an accident that nearly took her life in 1997: Babitz was severely burned when a cigar she was smoking while driving set fire to her skirt. (“I used to be charming,” she told a caregiver about her appearance as she healed.)

Afterward, she largely withdrew from public life. Once a ubiquitous presence who pervaded the Los Angeles worlds of art, literature and rock music, she fell into relative obscurity until, over the last few years, a new generation revived her reputation and legacy. This was in part thanks to the work of a biographer, Lili Anolik, who published “Hollywood’s Eve: Eve Babitz and the Secret History of L.A.” in 2019.

“She could be difficult, she could be perverse, but she was always a delight,” said Anolik. “I only knew her when her health was failing, and she was down maybe a marble or two, and she was still almost indecently charming: an easy laugher, loved to eat, and, if you got her talking about the past, told the best stories. Her bravura knowingness was intact until the end.”

Writer Brian Moore once said that despite its criticisms, Los Angeles is never provincial: “People in Southern California never look anywhere else in the world for instructions about what to think or how to behave.”

“I think it meant a great deal to her,” said Mirandi Babitz of her sister’s late-in-life literary comeback. “She was very thrilled that all these things had happened. I think she said a few times that it’s a little hard in your 70s to have all this attention, but she was very happy about it, that people really got her work.”

This story was originally published in October 2019. Iconic Los Angeles writer Eve Babitz died Friday at 78.

Even when writing about serious incidents, including the accident that changed her life, Babitz never lost her cutting yet curiously buoyant wit. “My friends would kill me if I died,” she recalled of the moment a paramedic arrived.

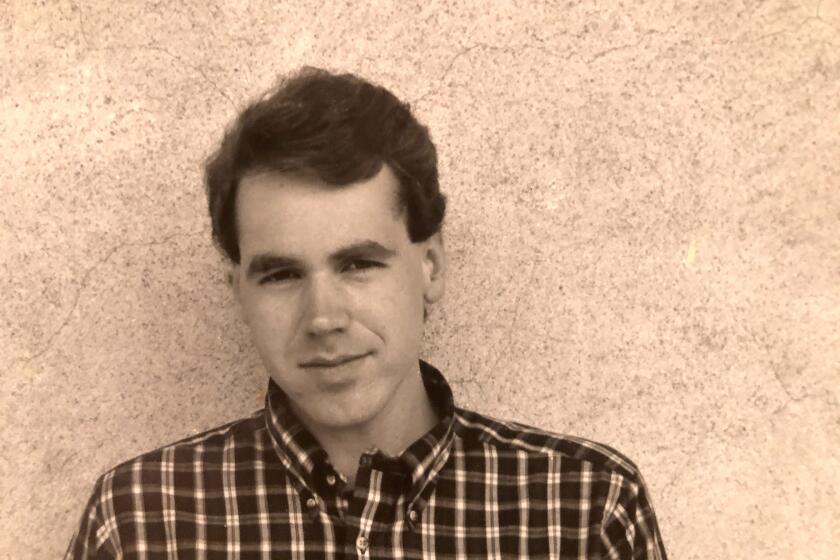

“She knew what she was doing,” said author Matthew Specktor, who wrote an introduction to the 2016 reissue of “Slow Days, Fast Company.” “She understood what she was writing and the way she was writing was not frivolous at all. But she was able to maintain a certain lightness of spirit or lightness of tone that doesn’t cancel out the work’s seriousness of purpose.”

Babitz was born in Los Angeles on May 13, 1943. Her father, Sol Babitz, was a violinist with the 20th Century Fox Orchestra, and her mother, Mae, was an artist. Her godfather was the composer Igor Stravinsky, and her young life was surrounded by bohemian friends of her parents. She attended Hollywood High School.

Eve Babitz’s resurgence reached its zenith Tuesday, with the publication of her first “new” (read: previously uncollected) work in decades.

In 1963, Babitz posed nude while playing chess opposite artist Marcel Duchamp in a photograph by Julian Wasser that would gain international notoriety. Babitz would later write in detail about the encounter in a piece collected in “I Used to Be Charming.”

After a time designing album covers for Atlantic Records, including releases by Buffalo Springfield, The Byrds and Linda Ronstadt, she turned her attention to her writing. Her first book, “Eve’s Hollywood,” was published in 1974.

Babitz was frequently compared to Joan Didion, who also channeled the spirit of Los Angeles in essays, though in style or affect they were near opposites. Among the uproarious, absurdly long dedications in “Eve’s Hollywood” — which also included the eggs benedict at the Beverly Wilshire and the sand dabs at Musso and Frank — Babitz mentioned Didion and her husband, John Gregory Dunne, by thanking “the Didion-Dunnes for having to be who I’m not.”

“Eve was perfectly in tune with the ultra-decadent, ultra-debauched 1970s, which happens to be the decade she was doing her best work in, and yet she was more or less ignored,” Anolik said. “Joan Didion, on other hand, became a superstar with 1967’s ‘Slouching Towards Bethlehem,’ a dark and anxious essay collection, written at the apex of the super-groovy, flower-child era. So Didion’s success — or at least the timing of Didion’s success — is as counterintuitive as the timing of Eve’s late-blooming vogue.

“Eve only became truly famous in the last six or seven years, during a period that could be described as puritanical or neo-Victorian, certainly not as fun-loving, which she and her books always were,” Anolik said. “My personal theory is that there’s a dominant mood to the moment; but then there’s a mood underneath that mood, and when you tap into the underneath-mood, you’ve really got something. If Didion was our secret superego then, Eve is our secret id now.”

Lili Anolik’s ‘Once Upon a Time ... at Bennington College,’ on the school days of Bret Easton Ellis, Donna Tartt and Jonathan Lethem, concludes this week.

Over time, Babitz’s work had largely fallen out of print. After the publication of a piece by Anolik in Vanity Fair in 2014, followed by reissues of her old books, the revival began to take off, with a new generation discovering the work, the persona and the survivor behind it. The unabashed quality of Babitz’s writing, its energy and unvarnished honesty, presaged the era of the online personal essay — perhaps another reason for its rediscovery.

“She’s a tremendously literary writer who carries that very effortlessly and that’s appealing, that’s kind of a good model for everybody,” said Specktor. “And of course, the fact that she cut such a figure, who wouldn’t want to be that on some level, who wouldn’t want to live that way? She had some fun and was not ashamed of both having that fun and interrogating it as a literary subject.”

She would bring her writing and say, ‘Who is going to kill me if I write this?’

— Mirandi Babitz on her sister, author Eve Babitz

Blurring the lines between essays and fiction, memoir and storytelling, Babitz made her life her art and her art her life in a way that might have been easier to envy from afar than it was for those caught in her orbit.

“She would bring her books to me before she published them,” recalled Mirandi Babitz. “She would bring her writing and say, ‘Who is going to kill me if I write this?’

“And of course sometimes I would get mad at her and I would give her cautionary warnings,” she added, “but I knew she was going to do it anyway. Because she had written it and it was always good, it was always true and interesting. So why not?”

People love an artist’s muse. The glamour of the position is naturally implied.