For the record:

10:16 a.m. Aug. 9, 2021This article incorrectly states, and earlier version of the headline incorrectly said, that Bobby Bowden had the most wins among major college football coaches. Penn State coach Joe Paterno had 111 wins reinstated by the NCAA in 2015, making him the career major football wins leader.

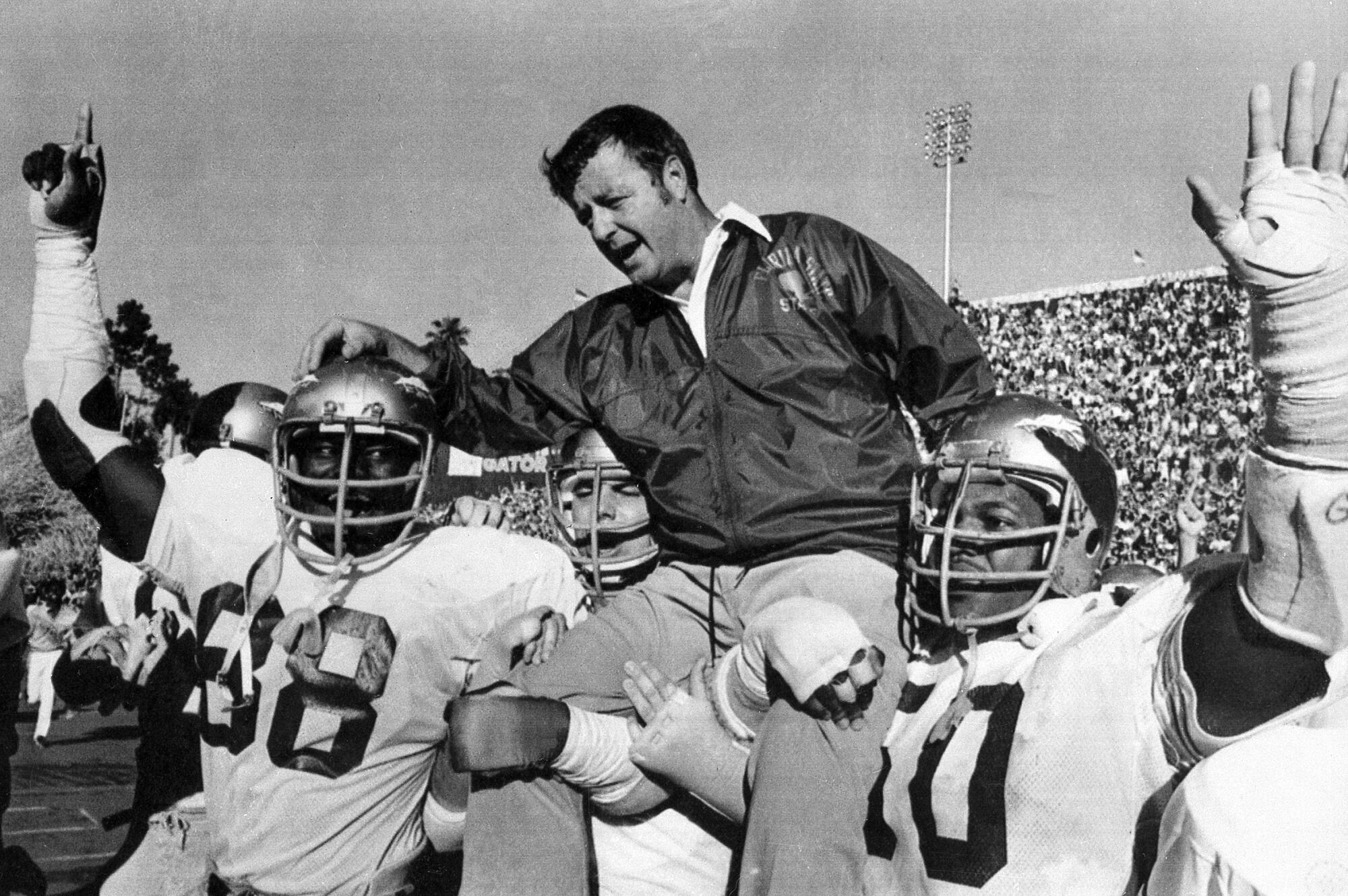

Bobby Bowden was an avuncular yarn-spinner who fused “fast-break” football and Southern charm to transform Florida State into a national college football powerhouse.

By the end of his career, he had more wins, 377, than any major college football coach.

Considered one of the greatest coaches and great characters in the game, Bowden died early Sunday morning at his northwest Florida home surrounded by his family after battling pancreatic cancer, his son Terry Bowden told reporters. He was 91 and had struggled with health issues since falling ill with COVID-19 in late 2020. In July 2021, Bowden told the Tallahassee Democrat he had been diagnosed with a terminal medical condition.

“I’m at peace,” he said.

As with most things involving Bowden, there’s a story that goes with his rise to the top.

He and his good friend Joe Paterno were once in a fast-track race to become the first major-division coach to reach 400 victories. The two stubborn icons battled it out into their 80s.

Paterno, Penn State’s longtime legend, won the race and finished with a Division 1-A record of 409 before his death in 2012.

Bowden ended with 389 wins, but 12 of those were vacated by the NCAA as part of academic fraud penalties levied on Florida State’s athletic department, leaving him with 377.

More than two years after his forced resignation in 2009, however, Bowden moved back to No. 1 as a result of the Jerry Sandusky sexual abuse scandal at Penn State.

Crippling NCAA sanctions handed down against Penn State included stripping Paterno of 111 wins, putting Bowden back on top.

“I wasn’t expecting it like this and didn’t want it to happen like this,” Bowden told the Gainesville Sun in 2012.

Bowden’s head-coaching arc spanned 44 years at three schools, and his accomplishments, primarily at Florida State, earned him a place in a pantheon alongside Paterno, Paul “Bear” Bryant, Knute Rockne and Pop Warner.

Florida State Coach Bobby Bowden sits in the vast leather chair behind the great wooden desk in his plush wood-paneled office and considers his 38-year career.

He was inducted into college football’s Hall of Fame in 2006. He insisted for years that Paterno should be remembered as the best, but a reassessment was required after the Sandusky story broke in November 2011.

Bowden thought the scandal involving an assistant Penn State coach who was convicted of molesting boys “put a taint” on Paterno’s legacy, and he reluctantly advocated for the removal of Paterno’s statue outside the Nittany Lions’ football stadium.

“I hate what happened at Penn State,” Bowden said, “but I hate more what happened to those young men.”

Bowden, like Paterno, was essentially fired at the end of a stellar tenure — albeit under extraordinarily different circumstances. Paterno couldn’t survive his connection to Sandusky, while Bowden’s ending was tied strictly to wins and losses.

After resurrecting Florida State over three decades from an also-ran to a national power, Bowden was forced out at age 80 after a 6-6 regular season in 2009. T.K. Wetherell, the school’s president, gave Bowden the option of returning for one last year as a figurehead coach, something Bowden would not accept.

Bowden finished with an overall record of 377-129-4, winning 304 games in 34 seasons at Florida State. He coached in 32 bowl games, but he never made a Rose Bowl appearance.

His last game, a 33-21 victory over West Virginia in the 2010 Gator Bowl, secured Bowden’s 33rd straight winning season.

“I wanted one more [year] and couldn’t have it,” he said after his final game. “They wouldn’t let me have it. But I can’t complain about nothing, y’all.”

FSU officials later worked to repair their relationship with Bowden, who was named an ambassador for the program, spoke at booster events and publicly supported his successors — Jimbo Fisher, Willie Taggart and Mike Norvell — through wins and losses. He was cheered again at Doak Campbell Stadium as he planted the traditional spear into the turf pregame in October 2013 and visited practices at the invitation of coaches. Bowden also regularly spoke to regional football clubs and at high school coaching clinics, staying connected to the game he loved until the COVID-19 pandemic forced him to shut down his public activities.

Florida State had won a total of four games in three seasons before his arrival in 1976. Four seasons later, Bowden led an 11-0 team to the Orange Bowl before losing to Oklahoma.

The day Bobby Bowden retires as Florida State coach will go down as one of the darkest days in the history of . . . sports journalism.

Bowden injected competitiveness, levity and foot speed into a step-slow program. His infectious personality and recruiting trail tenacity allowed him to attract some of the nation’s finest and fastest players to sunny Tallahassee.

He won two national titles (in 1993 and 1999), coached two Heisman Trophy-winning quarterbacks in Charlie Ward and Chris Weinke, and ushered in a fleet of talented players that included Deion Sanders, Warrick Dunn, Terrell Buckley, Marvin Jones, Corey Simon and Derrick Brooks.

Bowden was a Southern Baptist who didn’t drink or curse. He spoke in a colloquial cadence, punctuated with “dad-gummits,” that sometimes tempered the off-field controversies that periodically visited his program.

He was minister, motivator and historian, steeped in the study of World War II generals. Bowden related to modern players as he pined for days when criminal matters involving athletes were discreetly settled between, as he put it, “the coach and the chief of police.”

Criticized in 1999 for reinstating Peter Warrick after the star receiver was charged with receiving department store merchandise at a reduced cost, Bowden playfully wondered where a head coach might find that kind of discount.

Bowden had his limits.

“If I had a player commit murder, well now, I would just have to let him go,” he said before the 2000 Sugar Bowl.

Bowden’s game plan for putting Florida State on the football map included taking on the toughest competition. In 1981, the Seminoles played, in consecutive road games, at Nebraska, Ohio State, Notre Dame, Pittsburgh and Louisiana State — all national powers — and won three of five.

Bowden correctly calculated that once his teams started beating top programs, Florida State would quickly ascend in the polls.

In 1987, Florida State began an unprecedented string of success, compiling 14 straight 10-win seasons and 14 consecutive years with a final top-five Associated Press ranking.

Bowden’s teams won 11 straight bowl games in one stretch, and Florida State posted the best record in the 1990s — 109-13-1.

He also presided as unofficial patriarch of college football’s first family. He was married 71 years to Ann, his childhood sweetheart. Two of Bobby’s four sons, Terry and Tommy, became head coaches at Auburn and Tulane, respectively, among other schools. He is also survived by two other sons, Steve and Jeff; daughters Robyn and Ginger; and numerous grandchildren.

Bowden finally achieved perfection in 1999, leading 12-0 Florida State to its second national title. The Seminoles became the first team to go “wire-to-wire” as the No. 1 team in the Associated Press poll, from the beginning of the season until the end.

Florida State’s biggest scare that year was a road game that pitted Bobby against son Tommy, then the coach at Clemson.

Ann Bowden nervously watched, wearing a stitched-together jersey of both schools, although if push came to shove she was rooting for her husband.

Florida State’s hard-fought 17-14 win that night earned Bowden his 300th career victory.

Robert Cleckler Bowden was born Nov. 8, 1929, in Birmingham, Ala., in the belly of football country. Sometimes he and his father, Bob, a bank teller, would climb on the roof of the family’s home to watch football practices at nearby Woodlawn High, where Bobby would later star.

![In a crowd in the bleachers, a woman stands, holding a handwritten sign that says "We [heart] you Bobby."](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/b97450a/2147483647/strip/true/crop/3047x2120+0+0/resize/2000x1392!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F66%2Fcd%2F24ddddfa4d849fa555a5c1995ffb%2Fnc-state-florida-st-football.JPEG)

War and football were Bowden’s childhood companions.

At 13, he was stricken with rheumatic fever and spent his days monitoring radio accounts of World War II.

While bedridden for months, he became fascinated with the military giants — Erwin Rommel, George Patton, Douglas MacArthur — who plotted strategies and led soldiers in battle.

Bowden’s office bookcase at Florida State was filled with military biographies. He admired MacArthur’s cunning power and Patton’s fearlessness. Bowden kept figurines of Rommel and Patton in a cabinet behind his office desk.

In 2006, after Florida State finished 6-6 and was resigned to playing UCLA in a lower-tiered bowl in San Francisco, Bowden told The Times that even Napoleon had his Waterloo.

“He played in the Emerald Bowl, too,” Bowden quipped.

He recovered from his childhood disease to become a four-sport star in high school. A good enough quarterback to earn a scholarship offer at the University of Alabama, Bowden lasted only one semester in Tuscaloosa as lovesickness drove him back to Birmingham to marry Ann Estock. He was 19, she 16, when the couple eloped to Georgia in 1949.

Alabama didn’t allow married players on scholarship, so Bowden enrolled at Howard College (renamed Samford University in 1965) in Birmingham and earned honors at quarterback. He also earned a bachelor’s degree in education and, later, a master’s, also in education, from George Peabody College in Nashville.

He returned to Howard as head coach in 1959 and began making Tuscaloosa treks to cull wisdom from his idol, Alabama’s Bryant, who had become the Crimson Tide coach a year earlier.

Bowden left Howard in 1963 for an assistant’s position at Florida State and later served four years as West Virginia’s offensive coordinator before taking over as head coach in 1970.

Bowden had a 42-26 record in six years at West Virginia, but they weren’t all happy times. After his 1974 team finished 4-7, disgruntled fans staked “For Sale” signs in Bowden’s front lawn.

After a 9-3 rebound season and a Peach Bowl bid in 1975, Bowden accepted the challenge at Florida State. The school had gone 4-29 in the three seasons before Bowden’s arrival. He joked that the bumper stickers on West Virginia cars read “Beat Pitt,” the ones at Alabama read “Beat Auburn” and ones at Florida State read “Beat Anybody.”

Bowden went 5-6 his first year but never again suffered a losing season.

He turned Florida State football around quickly and would post nine 10-win seasons before finally earning his first national championship in 1993.

Many saw Florida State as a stepping-stone for Bowden. It made sense that he might some day return to Alabama to coach where the legendary Bryant coached, and there were opportunities that didn’t pan out.

But Bryant continued as a guiding influence.

Bowden worshipped Bryant but had his own style. He ushered in the era of the head coach as CEO. His strengths were procuring talent and delegating responsibility.

Bowden might have garnered more national titles if not for nemesis Miami.

Four times Miami handed Bowden teams their only defeat of the season. And Bowden’s 1991 team was 10-0 when it suffered a 17-16 loss at home in Tallahassee after kicker Gerry Thomas’ 34-yard field goal attempt skirted right of the upright.

Florida State lost its next game to Florida and finished 11-2.

A year later, in what became known as Wide Right II, Florida State kicker Dan Mowrey missed another late field goal that could have tied Miami. And, in 2000, Bowden endured Wide Right III, when Mike Munyon missed a late field goal in a three-point loss.

Bowden, years before his death, crafted the epitaph for his tombstone.

“But he played Miami,” he said.

Dufresne is a former Times staff writer who died in 2020.