Raymond Kappe dead at 92; California architect promoted prefab as environmentally friendly

For the record:

7:55 a.m. Nov. 26, 2019An earlier version of this story stated that Finn Kappe, one of Raymond Kappe’s sons, is a supervising architect with LivingHomes. Finn Kappe did spend time working with the company, but has since moved on.

Raymond Kappe’s first attempt to shape the future of California architecture ended in failure. After starting the architecture program at Cal Poly Pomona in 1968, he was fired as the department’s chairman. Kappe said it was because his program was too “free-swinging.”

Undaunted, he recruited six faculty members — future Pritzker Prize winner Thom Mayne, Ahde Lahti, Bill Simonian, Glen Small, Jim Stafford and Kappe’s wife, Shelly — to open a progressive architecture school. The New School, soon to become the influential Southern California Institute of Architecture, or SCI-Arc, opened in 1972 with 75 students at its original Santa Monica campus.

Kappe, who died Thursday at age 92, laid out SCI-Arc’s mission by placing an emphasis on social and cultural concerns. He used his stellar reputation in his role as founding director to attract faculty and students and served as director for the first 15 years and as chairman from 1998 to 2002.

Nearly 50 years later, alumni of the school — now an anchor of downtown L.A.’s Arts District in its location adjacent to the Los Angeles River — include architects Michael Rotondi, Dean Nota and John Souza, members of the so-called Santa Monica School of modern architecture, as well as Shigeru Ban, whose Naked House was named the Best House in the World by the World Architecture Awards in 2002.

“SCI-Arc would not have been possible without Ray Kappe,” said Rotondi, who went on to serve as SCI-Arc’s director, in a statement on Kappe’s passing. “His personality and character, his ideas, and most of all his visions were unique. Many of us would not have been possible without SCI-Arc.”

Kappe (pronounced KAP-ee) was also a prolific architect in his own right. He worked on more than 200 architectural projects, many of them embodying the California ideal of seamless indoor/outdoor living. Decades ahead of his time, his graceful modern houses were to advance the benefits of green building and, in some cases, revitalize communities.

“I design from the inside out,” Kappe told The Times in 1987. “My main concern is how a building works for the user and how it relates to and incorporates its surroundings.”

Experimentation boom

Kappe began his architectural career in the early 1950s, a golden time for residential and commercial experimentation in booming Southern California. And he remained a force until his death, passionately promoting prefabricated homes as an environmentally friendly, economic solution for hilly urban lots and flat desert outposts.

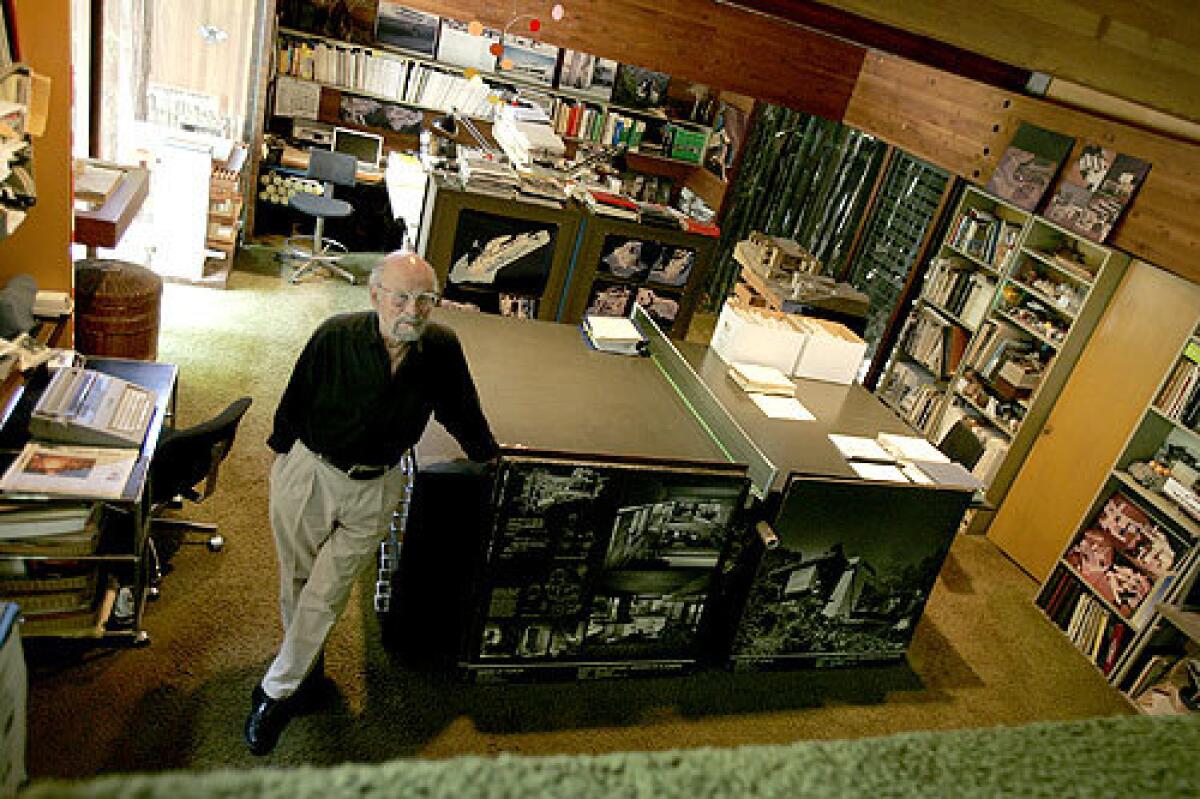

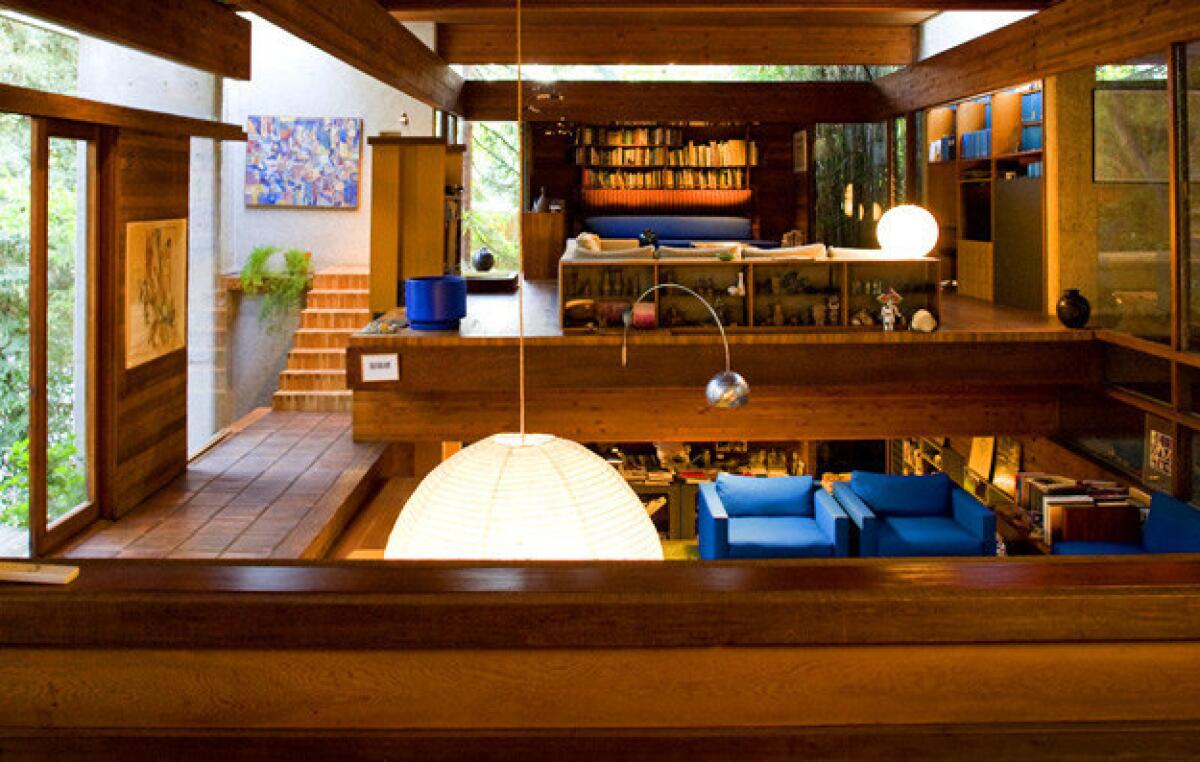

In 2006, Kappe unveiled an elegant, tiered house in Santa Monica made of 11 steel modules wrapped in sustainable cedar siding and glass. Ever the teacher, he wanted to show that a new breed of prefab boxes could be built quickly and efficiently in a factory, then delivered on a flatbed truck to the site and assembled by cranes on several levels. He was able to remove walls between rooms by staggering floors, a technique he used on his own Pacific Palisades residence, which allowed him to look up from his home office and see into his living room.

His 4,000-square-foot house, which he started designing in 1965 and had lived in since 1968, levitates on six concrete towers over a small stream, touching ground on only 600 square feet. He was able to buy the steep lot in 1962 for $17,000 because it had been deemed unbuildable.

The now-famous redwood dwelling was designated a historic cultural monument by the city of Los Angeles and has appeared in numerous publications and architectural books, including his 1999 monograph, “Themes and Variations: House Design Ray Kappe Architects/Planners (House Design, 3),” which he wrote with Michael Webb.

On the same Pacific Palisades street are six more of his keenly engineered houses, creating what was referred to as the Kappe Colony.

“I’m very into the idea of regionalism, trying to make places more appropriate to their location,” he once said. “People [in Southern California] are rather informal. We were attempting to be much more democratic and open after World War II, and L.A. exemplifies that.”

‘You know, architecture doesn’t have to do it all. The natural layer should show through too.’

— Ray Kappe

For most of his half-century career, his approach to modern was less about cold steel and more about arranging horizontal bands of Douglas fir and other wood to bridge gullies and creeks. He was adept at adapting multistory designs to slopes instead of cutting into hillsides and leveling the ground.

In many of his houses, walls of windows pressed against the branches of mature trees outside, creating a feeling of living in nature. He once told a reporter, “You know, architecture doesn’t have to do it all. The natural layer should show through too.”

Joe Addo of the A+D museum said before a 2004 exhibit of Kappe’s work, “His houses don’t shout at you, ‘I’m sexy.’ ... Ray’s is not only architecture, it’s home.”

Although he distinguished himself by designing timeless houses, Kappe took pride in his public and community projects. He practiced what he taught his students: Everyone benefits from thoughtful urban design and planning.

While he was with Kahn Kappe Lotery Boccato Architects/Planners in Santa Monica from 1968 to 1981, the firm created revitalization programs for Inglewood, a 255-unit affordable housing project in Pasadena, a conservation and land use plan for the city of San Clemente, a master plan for the Watts Community Arts Center and the Ramona Gardens Park with Barrio Planners, which was started by a group of Kappe’s former Cal Poly Pomona students.

Not one to pump the ego-stroking and sometimes career-making publicity machine, Kappe was well rewarded by architecture organizations such as the prestigious American Institute of Architects, but he sometimes felt overlooked by writers for national publications. He took offense in his soft-spoken way at journalists who elevated the role of 2005 Pritzker Prize winner Mayne in starting the private, tuition-funded SCI-Arc.

But no one at the school doubted his dedication to SCI-Arc. Often, he sacrificed his private practice and pay for his students. He once traded his consultation fee from modern furnishing retailer Design Within Reach for $31,000 in furniture for the SCI-Arc library, which he started in 1974 with a collection of his art and architectural books. In the early 1990s, it was named the Shelly & Ray Kappe Library.

Architect and former SCI-Arc director Eric Owen Moss mourned his colleague’s passing in the form of a poem: “Ray Kappe: The toughest task. Make something. From nothing. Not many do that. SCI-Arc, No, To SCI-Arc, Yes. An aspiration. Realized. Teach it. Draw it. Exhibit it. Lecture on it. Build it. Make it new. Ray Kappe: SCI-Arc. From nothing to something. History became the history he wrote.”

And in 2002, Mayne said, “Ray Kappe, long ago my mentor, had the vision, commitment and energy to initiate a totally unique ... educational model. Without his selflessness and his ability to mediate the diverse personalities necessary for a vital and creative architectural discourse, SCI-Arc could not have emerged into the institution it is today. His imprint remains at the core of this continuing experiment.”

Modern man

Kappe started his career in education in the early 1960s when he taught classes at USC. In 1977, he gave the keynote address at the national American Institute of Architects convention on the future of architectural education. Six years later, he founded SCI-Arc’s European program in Vico Morcote, Switzerland. In 1990, he received the Topaz Medallion, the highest award for excellence in architecture education, from the American Institute of Architects and the Assn. of Collegiate Schools of Architecture. In 2000, he helped secure a Santa Fe Railway freight depot building for SCI-Arc’s main campus downtown. And in 2006, he was given the Lifetime Achievement Award in Education at the American Institute of Architects convention in Los Angeles.

Kappe didn’t like the term “modernist” because he felt it was too trendy; he wanted his contributions to last. He embraced the term “modern” instead because it represented a desire to be current with the latest ideas, technologies and materials, he said. In the 1960s, he designed modular, prefabricated student housing for Sonoma State University that was never built. And in the 1970s, before the first Earth Day, he used recycled redwood and energy- and water-saving systems in houses. His prefab Santa Monica house for LivingHomes in 2006 was the first residence to receive the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design highest rating from the U.S. Green Building Council.

Kappe was born Aug. 4, 1927, in Minneapolis. As a child, he liked to draw and did well in math and science. He grew up living in an apartment and told reporters that he would often stand at the windows looking out. “It’s been kind of a theme in my work, to extend out to the views,” he said. “I’ve always sought out the edges ... and a feeling of expansiveness. That’s the common denominator in my architecture.”

After graduating from UC Berkeley in 1951, he worked for the San Francisco firm of Anshen + Allen, a designer of modern houses for middle-class buyers built by Joseph Eichler in the Bay Area and Southern California. He also worked for Los Angeles modern architect Carl Maston, who designed apartment buildings.

Kappe opened his own practice in Santa Monica in 1953, and while living with his wife in Sherman Oaks, he built post-and-beam houses with living rooms that lead into patios in the San Fernando Valley.

After dissolving his partnership with the other urban planning architects at Kahn Kappe Lotery Boccato Architects/Planners in 1981, he continued his private practice under the name of Kappe Architects Planners. From 1985 to 1990, he partnered with his two sons, Ron Kappe, an architect who now has a community and residential practice in San Rafael, Calif., and Finn Kappe, a Santa Monica-based architect, who for a time worked with LivingHomes. The father-and-sons firm worked on the University Faculty Office building for Cal State San Bernardino, the Hilton Beach Hotel in Oxnard, a mixed-use project in Oakland and several custom homes.

Kappe’s death came after contracting pneumonia, according to the Architect’s Newspaper. His passing was confirmed by SCI-Arc.

In addition to his sons and wife Shelly, whom he married in 1950 and collaborated with throughout their careers, Kappe is survived by his daughter, Karen Kappe, a psychologist and artist in Vancouver, Canada.

When his sons launched their own firms, Kappe went back to his one-man shop specializing in custom residences and prefabricated modular housing.

“I think it’s easier to do a lot than a little,” he once said. “You use your support better. And I always designed quickly. Houses are a great laboratory for experimenting with design and construction ideas.”

In 2007, when many named architects were seeking the highest bidder for their archives, Kappe donated thousands of his drawings, wood-block models and notes to the Getty Center to make them accessible to designers, students, homeowners and neighborhood preservation groups.

Before the Getty Research Institute took possession of the archive, head of special collections Wim de Wit said the Getty was willing to repair, store and open the archive to the public because “Ray Kappe is incredibly important and his importance will grow. He designs beautifully detailed wood structures and he was one of the earliest to use sustainable materials and to understand that we can live in an environment without damaging it.”

Eastman is a former Times staff writer. Randall Roberts contributed to this report.