Obama marks ‘Bloody Sunday’ anniversary: ‘Our march is not yet finished’

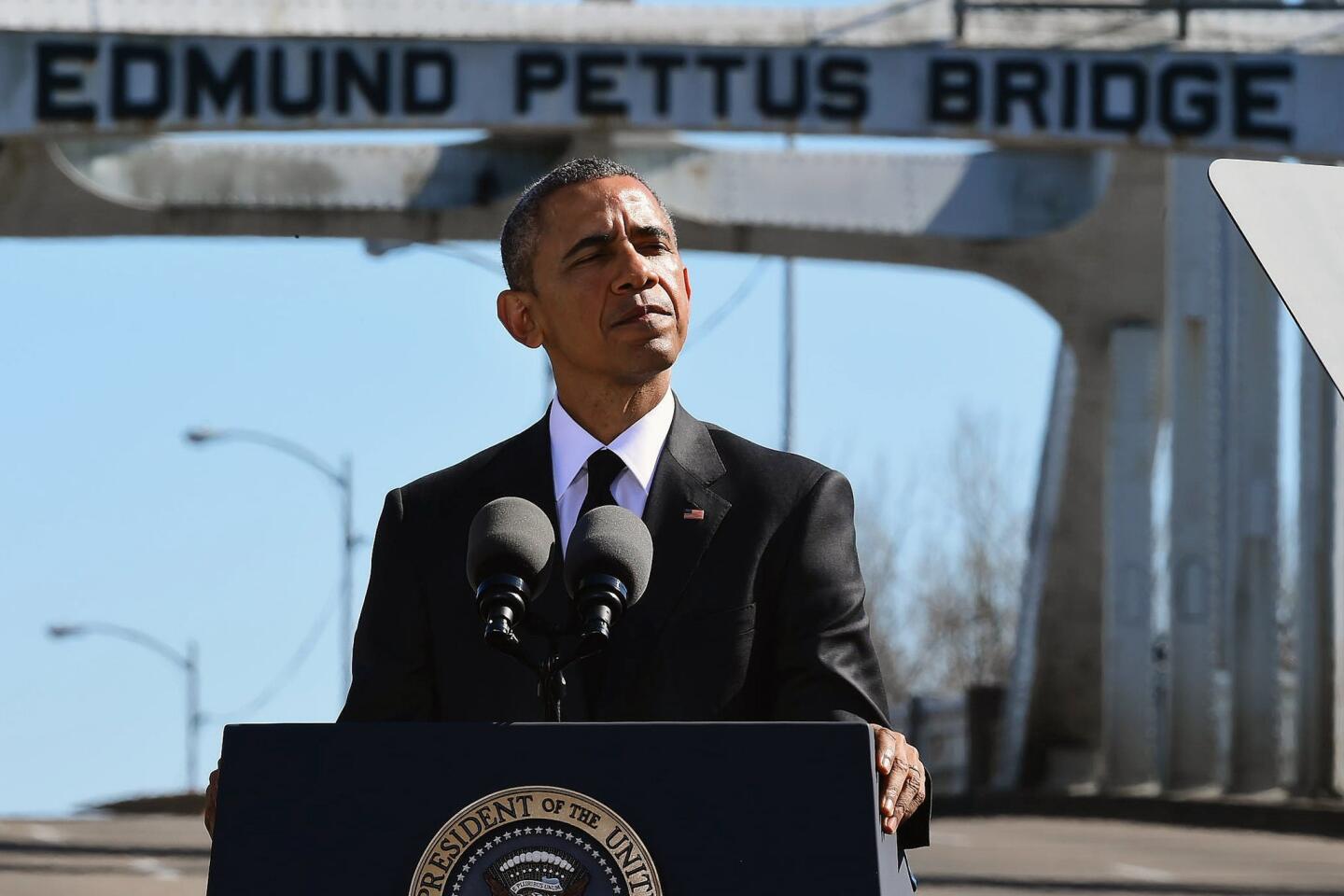

Reporting from Selma, Ala. — Standing before the landmark Edmund Pettus Bridge to commemorate a historic moment in the civil rights movement, President Obama on Saturday called upon Americans to acknowledge progress the nation has made in easing racial tensions but remain vigilant for the hard work still ahead.

“Fifty years from ‘Bloody Sunday,’ our march is not yet finished,” Obama told a crowd of several hundred black and white faces gathered on the 50th anniversary of the Selma march, when Alabama police brutally beat black protesters demanding access to the ballot.

“But we are getting closer,” Obama said. “Our job’s easier because somebody already got us through that first mile. Somebody already got us over that bridge.”

As the nation’s first African American president, Obama has often been expected to serve as a bridge himself, for America’s racial divide. Following the unrest triggered last summer by the shooting death of an unarmed black man by a white police officer in Ferguson, Mo., and incidents in other cities, the president has struggled to help define and guide a civil rights movement for the next generation.

In a soaring speech delivered at nearly the same time and spot that demonstrators were attacked by state troopers and local law enforcement 50 years earlier, Obama urged Americans to shed cynicism and complacency, and embrace individual responsibility and the “imperative of citizenship.”

As the president spoke, the crowd drowned out the ends of his sentences with applause and cheers. Teenagers strained to see and take pictures with their smartphones. Older faces were wet with tears.

His address came just days after the Justice Department released a report excoriating the city of Ferguson for a pattern of discrimination against blacks. But Obama dismissed the idea that the injustice in Ferguson showed that race relations hadn’t changed much in the U.S.

True, he said, the report’s narrative was “woefully familiar.”

“But I rejected the notion that nothing’s changed,” Obama said. “What happened in Ferguson may not be unique, but it’s no longer endemic. It’s no longer sanctioned by law and custom. And before the civil rights movement, it most surely was.”

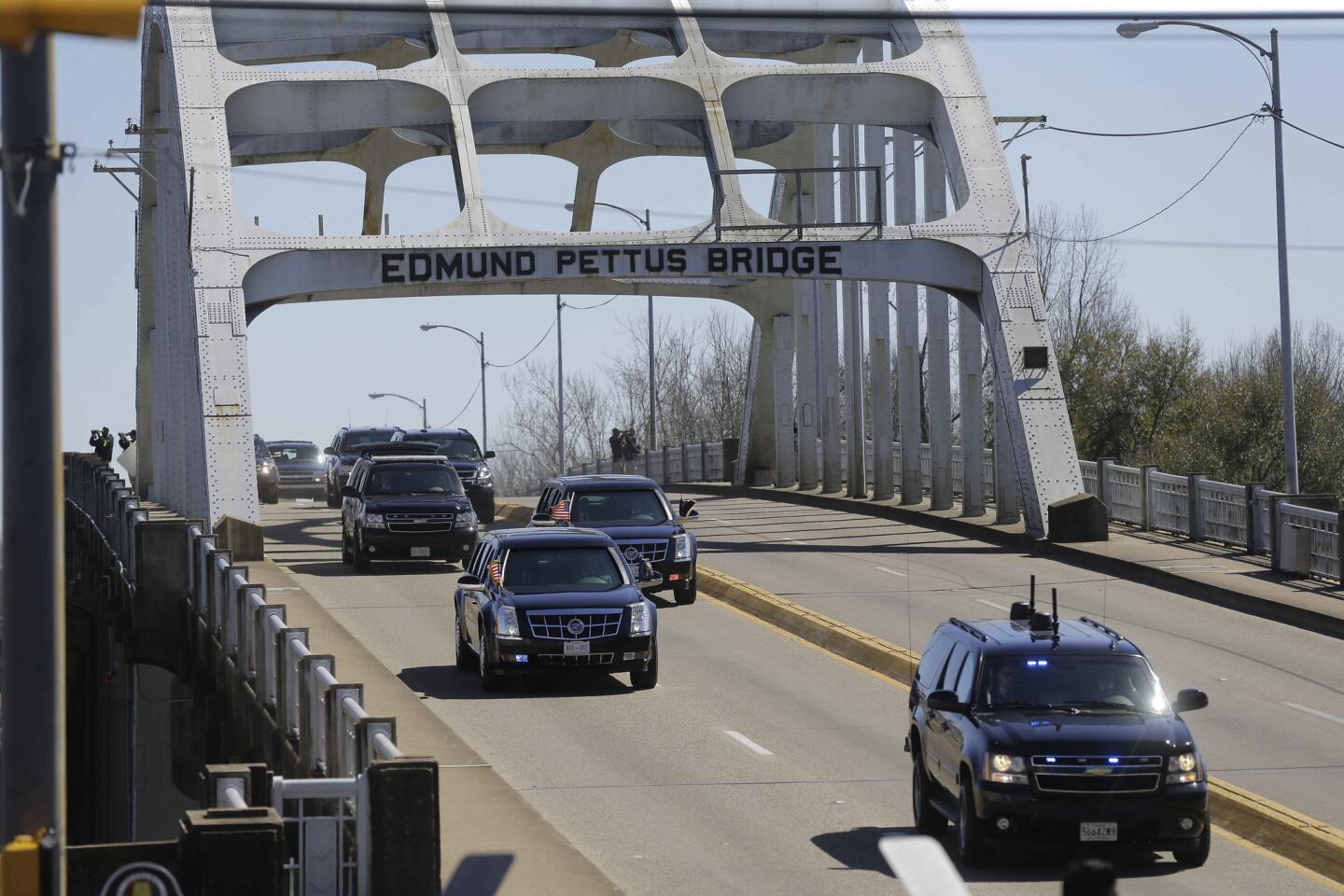

When he was finished, the president, first lady and their daughters, Malia and Sasha, joined U.S. Rep. John Lewis of Georgia, who was badly injured in the original Selma march, former President George W. Bush and about 100 officials in a symbolic march across the steel bridge, painted white with black block letters spelling out the name of a onetime Ku Klux Klan leader.

Obama used the opportunity to call on members of Congress to restore the full protections of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. And he admonished Americans for too often squandering their voting rights, noting that it was a privilege that past generations had fought hard to win.

He questioned how Americans today could turn out in such small numbers to vote and tolerate passage of new state and local laws designed to make it harder for people to do so.

The Voting Rights Act, “the culmination of so much blood and sweat and tears, the product of so much sacrifice in the face of wanton violence, stands weakened, its future subject to partisan rancor,” Obama said.

“How can that be?” he asked. “The Voting Rights Act was one of the crowning achievements of our democracy, the result of Republican and Democratic efforts. President Reagan signed its renewal when he was in office. President George W. Bush signed its renewal when he was in office.

“One hundred members of Congress have come here today to honor people who were willing to die for the right it protected,” he said. “If we want to honor this day, let that hundred go back to Washington and gather 400 more, and together, pledge to make it their mission to restore that law this year.”

Dozens of lawmakers, Republican and Democrats alike, made the pilgrimage to Selma to mark the occasion. Rep. Martha Roby, a white Alabama Republican, co-hosted the event with Rep. Terri A. Sewell, a black Alabama Democrat and Selma native.

As Obama spoke, a group of about 20 young people, mostly black, began to wave signs reading “Black lives matter” and chanted, “We want change,” as a drummer thumped out a beat.

Alabama state troopers stood by and watched as a group of older black men waded into the crowd and began to talk to the demonstrators, who quieted after about five minutes.

The Selma marchers of 1965 saw a different response to their protest. Images of the brutal attacks of that day, now viewed as a galvanizing moment of the civil rights era, shocked the country and helped to fuel passage of the Voting Rights Act a few months later. The law prohibited state or local officials from enacting any voting law that results in discrimination against minorities.

Today, though, the law stands weakened by a 2-year-old Supreme Court decision that freed states, mostly in the South, to change their election laws without getting federal approval in advance, basically doing away with the enforcement mechanism of the 1965 act. Many believe that voter identification laws passed since have particularly inhibited minority voters.

In its 2013 decision, the court majority said Congress could still impose federal oversight in states where voting rights were at risk. Lawmakers have not forged an agreement on where federal oversight is needed.

The job doesn’t just belong to Congress, Obama said. Even if every new voter suppression law were struck down today, he said, the U.S. would still have one of the lowest voting rates of any democracy in the world.

“Fifty years ago, registering to vote here in Selma and much of the South meant guessing the number of jelly beans in a jar or number of bubbles on a bar of soap,” he said. “It meant risking your dignity, and sometimes your life.

“What’s our excuse today for not voting?” Obama said. “How do we so casually discard the right for which so many fought? How do we so fully give away our power, our voice, in shaping America’s future?”

Obama called the Selma march a defining moment in U.S. history that resonated around the world, inspiring others to rise up against oppression and tyranny.

“There are places and moments in America where this nation’s destiny has been decided,” he said. “Selma is such a place.”

The standoff, the president said, was “not a clash of armies, but a clash of wills; a contest to determine the true meaning of America.” He said the march proved that “hope can conquer.” Marchers did reach Montgomery, on the third attempt, days later.

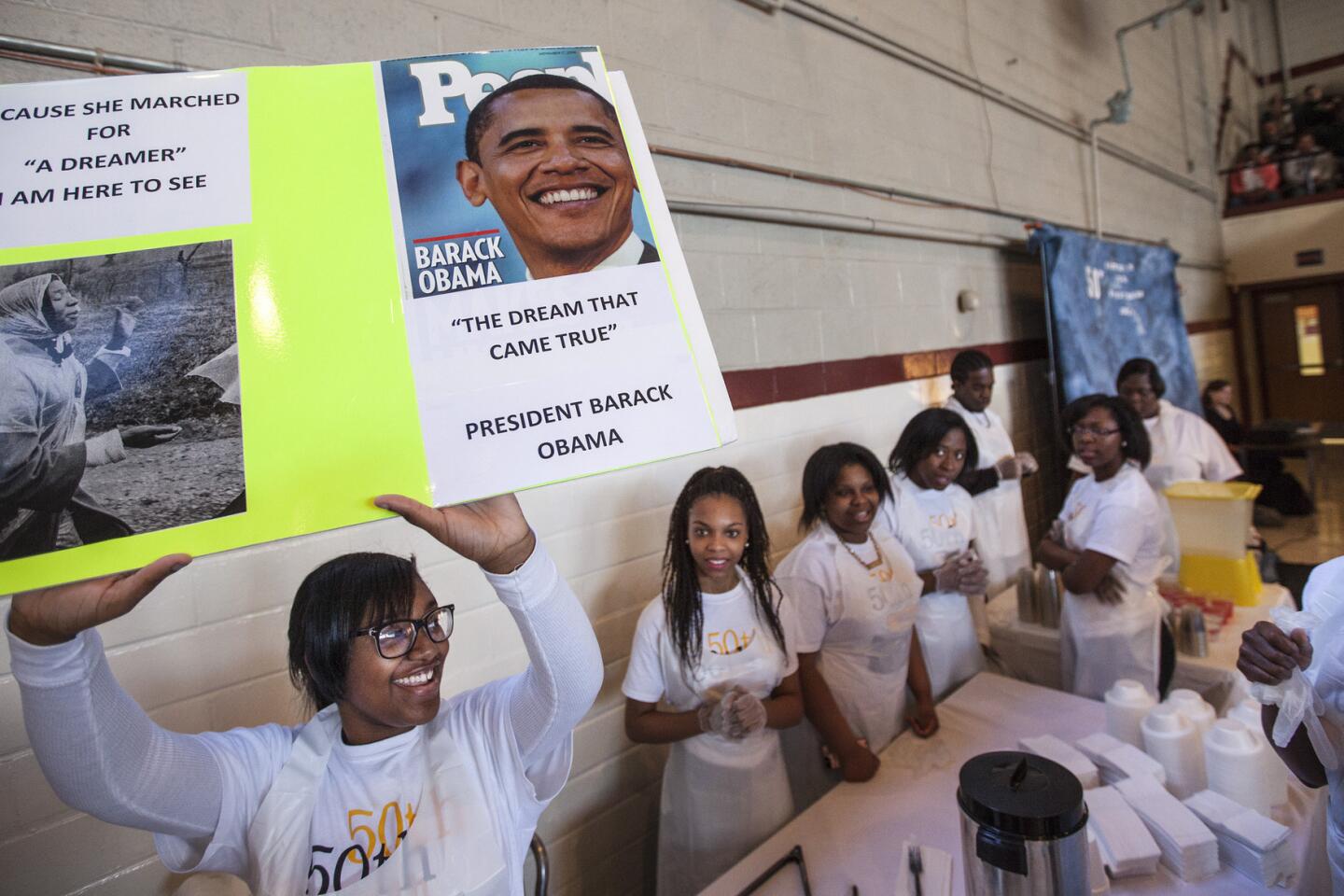

The image of the first African American president standing in front of the empty Edmund Pettus Bridge was a powerful one for Melanie Campbell, 50, a community organizer who traveled from Virginia for the anniversary.

“Seeing him at that bridge, thinking how far we came to get him there, that makes me feel like we’ve come so far,” Campbell said.

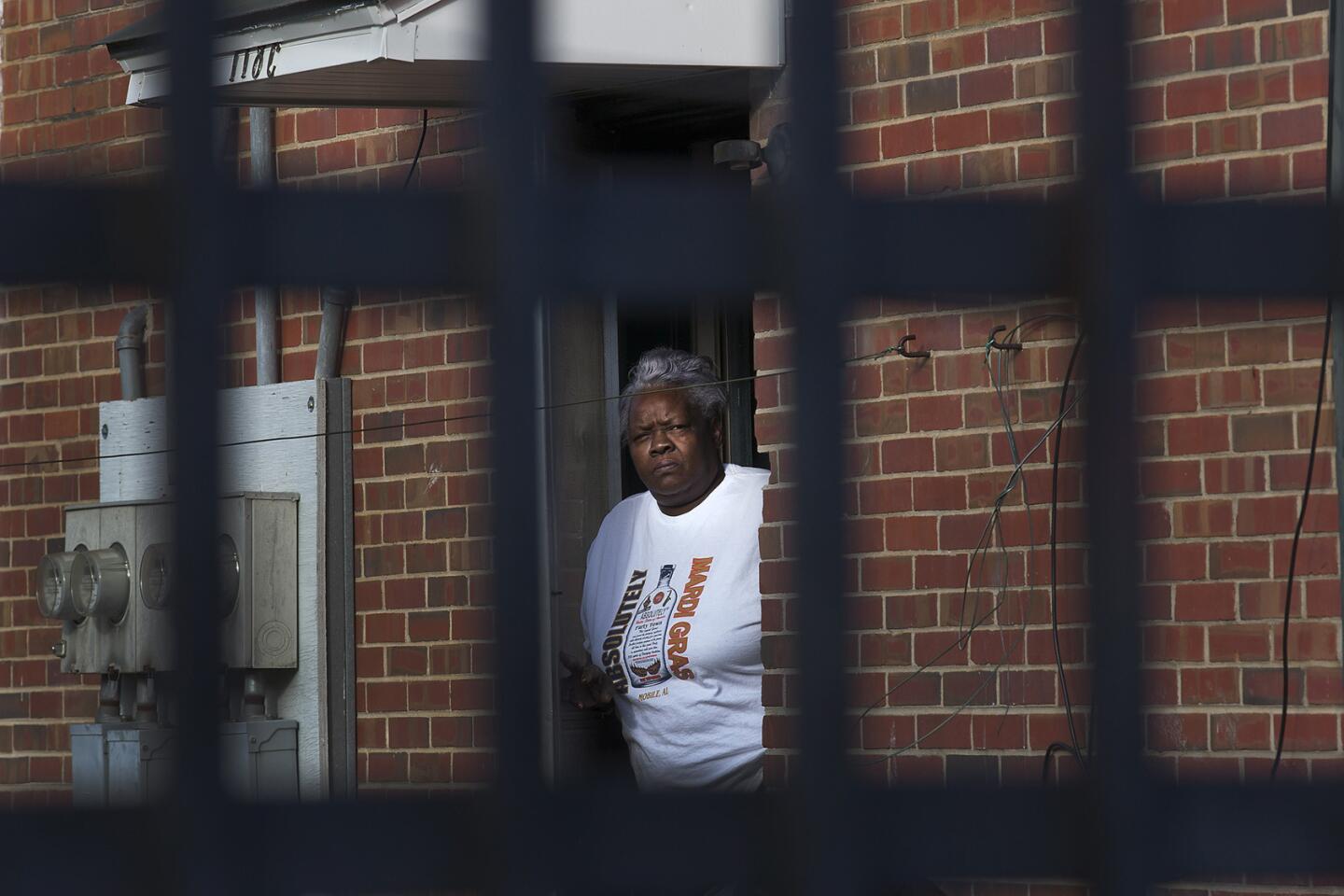

At the same time, another political activist in the crowd said she felt a pang of sadness because, she said, the country was still fighting the same fight.

“I hear that we can’t get a new Voting Rights Act, and I want to know, why not?” said LaTosha Brown, 44, a Selma native who works as a project director for a group called Grantmakers for Southern Progress.

“How can you be against that?” she asked. “We are hoping people will be inspired by what the president says.”

The struggle for voting rights continues to be a “sacred fight” for Americans, said Jonathan Bass, a civil rights historian and head of the history department at nearby Samford University.

“In this historical context, it’s a stark contrast when you look at all of these limitations placed on the franchise,” said Bass. “It’s disturbing for many black activists who are seeing a slow retrenchment of the voting rights that were earned in the ‘50s and ‘60s.”

Still, the appearance Saturday of the first black American president speaks as a partial fulfillment of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream, he said.

“I think he would be deeply moved by that,” said Bass. “In an age of hyperpartisanship, an age where nothing is done without some sort of political calculation, this truly transcends politics.”