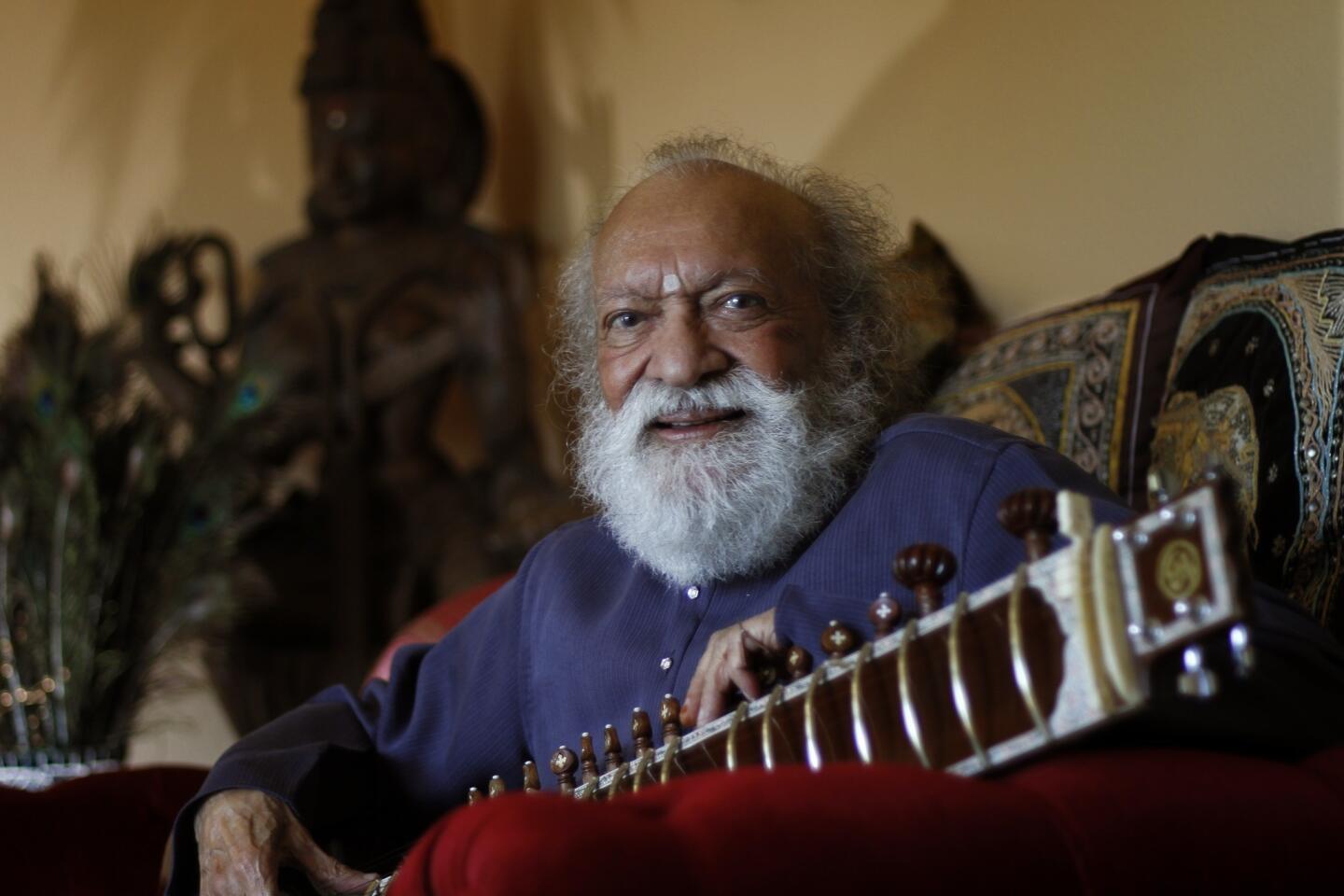

Ravi Shankar dies at 92; sitar master

Ravi Shankar was already revered as a master of the sitar in 1966 when he met George Harrison, the Beatle who became his most famous disciple and gave the Indian musician-composer unexpected pop-culture cachet.

Suddenly the classically trained Shankar was a darling of the hippie movement, gaining widespread attention through memorable performances at the Monterey Pop Festival, Woodstock and the 1971 Concert for Bangladesh.

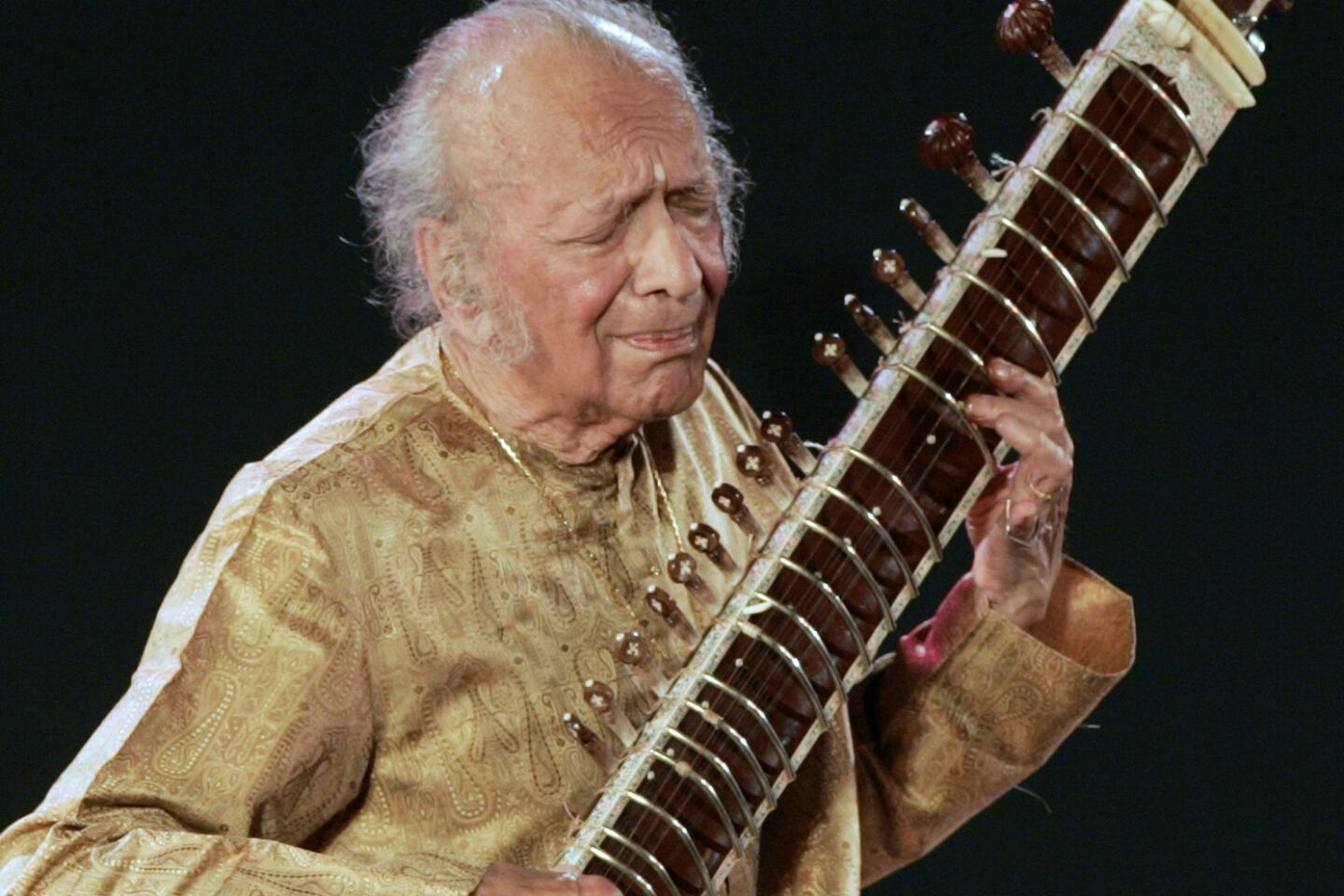

Harrison called him “the godfather of world music,” and the great violinist Yehudi Menuhin once compared the sitarist’s genius to Mozart’s. Shankar continued to give virtuoso performances into his 90s, including one in 2011 at Walt Disney Concert Hall.

PHOTOS: Ravi Shankar | 1920 - 2010

Shankar, 92, who introduced Indian music to much of the Western world, died Tuesday at a hospital near his home in Encinitas. Stuart Wolferman, a publicist for his record label Unfinished Side Productions, said Shankar had undergone heart valve replacement surgery last week.

FOR THE RECORD:

Ravi Shankar: The obituary of Indian sitar master Ravi Shankar in the Dec. 12 LATExtra section said that his son Shubhendra died in 1989. Shubhendra Shankar died in 1992.

Well-established in the classical music of his native India since the 1940s, he remained a vital figure on the global music stage for six decades. Shankar is the father of pop music star Norah Jones and Anoushka Shankar, his protege and a sitar star in her own right.

Before the 1950s, Indian classical music — with its improvised melodic excursions and complex percussion rhythms — was virtually unknown in America. If Shankar had done nothing more than compose the movie scores for Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray’s “Apu” trilogy in the 1950s, he “would be remembered and revered,” Times music critic Mark Swed wrote last fall.

PHOTOS: Notable deaths of 2012

Shankar was on a path to international stardom during the 1950s, playing the sitar in the Soviet Union and debuting as a soloist in Western Europe and the United States. Two early albums also had considerable impact, “Three Classical Ragas” and “India’s Master Musician.”

During his musical emergence in the West, his first important association was with violinist Menuhin, whose passion for Indian music was ignited by Shankar in 1952. Their creative partnership peaked with their “West Meets East” release, which earned a Grammy Award in 1967. The recording also showed Shankar’s versatility — and the capacity of Indian music to inspire artists from different creative disciplines.

He presented a new form of classical music to Western audiences that was based on improvisation instead of written compositions. Shankar typically played in the Hindustani classical style, in which he was accompanied by a player of two tablas, or small hand drums. Concerts in India that often lasted through the night were generally shortened to a few hours for American venues as Shankar played the sitar, a long-necked lute-like stringed instrument.

At first, he especially appealed to fans of jazz music drawn to improvisation. He recorded “Improvisations” (1962) with saxophonist Bud Shank and “Portrait of a Genius” (1964) with flutist Paul Horn, gave lessons to saxophonist John Coltrane (who named his saxophone-playing son Ravi), and wrote a percussion piece for drummer Buddy Rich and Alla Rakha.

On the Beatles’ 1965 recording “Norwegian Wood,” Harrison had played the sitar and met Shankar the next year in London.

Shankar was “the first person to impress me,” among the impressive people the Beatles met, “because he didn’t try to impress me,” Harrison later said. The pair became close and their friendship lasted until Harrison’s death in 2001.

Harrison was instrumental in getting Shankar booked at the now legendary Monterey Pop Festival in 1967. They partnered in organizing the Concert for Bangladesh and were among the producers who won a Grammy in 1972 for the subsequent album. They toured together in 1974, and Harrison produced Shankar’s career-spanning mid-1990s boxed set, “In Celebration.”

But Shankar came away from his festival appearances with mixed feelings about his rock generation followers. He expressed hope that his performances might help young people better understand Indian music and philosophy but later said “they weren’t ready for it.”

“All the young people got interested … but it was so mixed up with superficiality and the fad and the drugs,” Shankar told The Times in 1996. “I had to go through several years to make them understand that this is a disciplined music, needing a fresh mind.”

When Shankar was criticized in India as a sellout for spreading his music in the West, he responded in the early 1970s by lowering his profile and reaffirming his classical roots. He followed his first concerto for sitar and orchestra in 1971 with another a decade later.

“Our music has gone through so much development,” Shankar told The Times in 1997. “But its roots — which have something to do with its feelings, the depth from where you bring out the music when you perform — touch the listeners even without their knowing it.”

In the 1980s and ‘90s, Shankar maintained a busy performing schedule despite heart problems. He recorded “Tana Mana,” an unusual synthesis of Indian music, electronics and jazz; oversaw the American premiere of his ballet, “Ghyanshyam: The Broken Branch”; and collaborated with composer Philip Glass on the album “Passages.”

With his wife, Sukanya, and daughter Anoushka, Shankar moved to Encinitas in 1992 but spent several months a year in India. He devoted much of his time to establishing the Ravi Shankar Foundation for Indian music education, based in Encinitas, and a similar center in New Delhi. In 2001, he received his final Grammy, in the world music category, for “Full Circle.”

He was born Robindro Shankar on April 7, 1920, in Varanasi, India, to a Brahmin family. The youngest of four sons who survived to adulthood, he changed his name to Ravi, meaning “sun,” when he was 20. His father, Shyam Shankar, was a scholar and lawyer who was absent for most of Ravi’s childhood.

At 10, Ravi moved to Paris with his mother to tour with his brother Uday Shankar’s Company of Indian Dancers. In 1938, the great sarod player Allauddin Khan joined the troupe as a guest artist in the U.S., and Shankar was drawn back to Indian classical music. He returned to India to study the sitar with Khan for seven years.

His 1969 autobiography, “My Music, My Life,” is considered one of the best general introductions to Hindustani music.

When Shankar performed last year at Disney Hall, Times reviewer Swed wrote that “he opened ears and remade sensibilities” — and deserved to be called a legend.

Shankar’s personal life was complicated. In 1941, he married Annapurna Dvi Allaudin, the daughter of Allauddin Khan and sister of master Indian musician-composer Ali Akbar Khan. The couple had a son, Shubhendra, and divorced in 1958. His son died in 1989.

Shankar had relationships with dancer Kamala Sastri, Sukanya Rajan and concert producer Sue Jones, who is Norah’s mother. He married Rajan in 1989.

Besides his wife and daughters, he is survived by grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Times staff writer Valerie J. Nelson contributed to this report.