Disaster after disaster, California keeps falling short on evacuating people from harm’s way

Reporting from Paradise, calif. — Leigh Bailey, 54, was awakened not by her phone, warning her about an incoming fire that would soon destroy her town, but by a neighbor pounding on her door.

Bailey had no idea how bad the fire was about to become. So she went back inside around 9:15 a.m., had a cup of tea and ate some coffee cake and slowly packed some clothes and her dog and cat before heading out of her home in Magalia, just north of Paradise.

She escaped — but barely, on a narrow dirt road she stumbled on despite driving through thick smoke and the failure of her GPS.

“We had absolutely no evacuation orders,” Bailey said. “No call, no emergency text, nothing — and neither did anyone I know.”

This has been a recurring problem.

More than 140 people have died in California over the last 13 months from various calamities, ranging from the fires in wine country to the mudslides in Montecito.

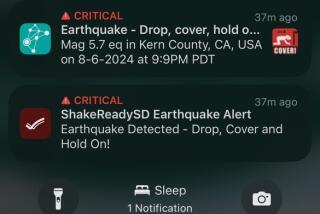

In many of these disasters, officials have acknowledged flaws in the evacuation plans, including the failure to use the latest technology to broadcast Amber Alert-style warnings on cellphones ahead of deadly disasters.

But when the worst fire in California history moved into Paradise this month, the evacuation plan fell short, with officials using an older alert system that reached only a fraction of the town instead of the federal government’s Wireless Emergency Alert system, known as WEA, which would have reached far more people.

“In both the [wine country] fire and the [Paradise] fire, if you look at the growing number of fatalities — they were people who were in their house or running to their car. That’s indicative of a population that was never alerted. They didn’t see anything on their TV, radio, nothing,” said Thomas Cova, director of University of Utah’s Center for Natural and Technological Hazards. “We are not using all the tools we could to communicate with people.”

LIVE UPDATES: The latest on the California wildfires »

In both of those fire areas and in many other local jurisdictions, officials rely on older emergency warning systems that reach a dwindling number of landline phone lists and cellphone numbers voluntarily submitted by residents. Those numbers represent only a fraction of the population.

“They’re using outdated technology,” Cova said. “We’re learning the same things from the Camp fire that we already learned from the Tubbs fire.”

Emergency managers should use all the available tools in getting the word out about a risk to life — whether it be Wireless Emergency Alert texts or going door-to-door, said Richard Rudman, vice chair of the California Emergency Alert System’s emergency communications committee.

“They need to open up the entire toolkit and use everything,” Rudman said. “You never know who you’re going to miss, or who you’re going to hit.”

The Times has reported that Paradise officials initially limited evacuation orders to just the side of town closest to the fire — hoping to keep the limited exit routes clear for those who needed to escape first. Some residents heard of the evacuation order from police cars driving by, barking the warnings through a loudspeaker. Others had to find out by door knocks or text messages from neighbors.

The strategy failed — the fire moved too fast. By the time officials issued an order to evacuate the rest of the city, the CodeRed telephone warning system was too slow to blanket the town with an immediate warning.

It’s a scenario hauntingly similar to what happened in wine country last year.

Sonoma County Sheriff’s officials faced criticism for not sending a blanket alert over the Wireless Emergency Alert system as the Tubbs fire leaped from wildlands into town. Officials defended the decision, saying the system wasn’t precise geographically and could needlessly warn people outside of the immediate zone of danger, unnecessarily causing them to jam roads. There was also a discussion of the limits of WEA text messages, which allow only 90 characters.

Yet the result was that many people were caught unaware about the fire’s path until it put them at risk; some were awakened when the flames were on their doorsteps. At least 22 people died as the flames swept into populated areas overnight; many who survived said they heard of the danger only from door knocks and firefighters shouting at sleeping residents to flee.

“A timely abbreviated message is preferable to a thorough message delivered too late,” concluded the report by the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services.

The chairman of the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors, James Gore, said during emergencies, government should “do everything in our power to notify everybody” in harm’s way.

“The first thing is that people need to know what the hell is going on,” Gore said. “And if you have situational awareness, you need to share it. Would that have changed anything? Who knows. But at least we would’ve known we did that.”

It’s true there are problems with the system, he acknowledged. “But in imperfect times, you have to be relentless about getting word out and letting people know what’s going on,” Gore said.

Another problem in recent fires was how the wind-whipped blazes moved so fast that firefighters weren’t always certain where the flames were. Local governments need to improve their ability to quickly understand where the fire is headed — the Tubbs fire leaped over a length in four hours that it took the Hanley fire of 1964 a day and a half, Gore said.

As a result, Sonoma County is investing in fire camera systems, approving earlier this year spending $500,000 to install eight of them for live broadcasting on www.alertwildfire.org. They are infrared cameras — helpful to see the heat of the fire through smoke. During the Tubbs fire, the smoke was so thick it was difficult to track the progress of a fire that was moving the length of a football field every minute, Gore said.

“You’re talking about a fire line that is shooting mortar fire in front of it,” Gore said.

Deadly California fires prompt bold thinking about prevention »

Sonoma County is also looking at installing siren systems, such as in areas without reliable cellphone service, as well as along the coast to warn of a tsunami and near dams to warn of a breach.

“You can’t trust tech all the time,” Gore said. During the Tubbs fire, “the connections to the cell towers burned down…. Verizon was completely off the grid for everybody in our community. Comcast was down for a week.”

Some cities still use air sirens, like San Francisco, which tests its citywide system every Tuesday at noon. In a real emergency, residents can get emergency information from their radios. Newport Beach recently installed three emergency sirens on its coast.

Sometimes local officials don’t issue alerts on the Wireless Emergency Alert system because they lack information on how to use it. After criticism of San Jose’s lack of widespread warning to residents of incoming floodwaters in January 2017, an internal report said “there was a general lack of institutional knowledge” on how to broadcast alerts on that system.

This past January, a WEA message wasn’t sent out until hillsides were already dissolving into a river of mud, debris and boulders in Montecito, killing more than 20 people. When rains returned in March, officials sent out a WEA message 12 hours before the storm was estimated to arrive, telling people that an evacuation was underway and that they should visit a county website for more information.

In Los Angeles, Controller Ron Galperin in August criticized officials for not sending a Wireless Emergency Alert to notify residents of an initial evacuation order for last year’s Creek fire in Sylmar.

The city should err “on the side of more information to ensure the widest possible audience during potentially dangerous situations,” Galperin wrote.

Los Angeles recently used the Wireless Emergency Alert system to notify residents in an area of West Hills during the Woolsey fire, said Kate Hutton, a spokeswoman for the city’s emergency management department.

“There is a level of comfort that grows as you use the system,” Hutton said. “We have not ever, in my experience, had any panic from the public.”

Last year, state officials took an unprecedented step of issuing a Wireless Emergency Alert for seven Southern California counties that simply said: “Strong winds overnight creating extreme fire danger. Stay alert. Listen to authorities.” Experts thought it was a prudent use of the system.

In areas where telephone coverage is unavailable, buying a so-called National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration weather radio may be a good option. Weather radios can have features that beep before an urgent message is broadcast about an imminent fire warning issued by local law enforcement, which the National Weather Service can transmit over its frequency.

Track key details of the California wildfires »

Malibu residents are demanding improvements in emergency notifications.

Movie director Damien Chazelle, who lives in Malibu, said it took friends miles away from the Woolsey fire, in West Hollywood and Los Angeles, to warn him and his wife to evacuate.

“And as we got on the road and drove out, we passed several people, just out walking dogs — and we would kind of pull over, ask if they’d heard about the evacuation,” Chazelle told the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors. “And in all cases, they hadn’t heard anything.”

“There was not really a system of everyone finding out what was going on,” Malibu resident Shelby Meade said. “How can we — with knowing we’re going to have possible landslides coming — have a better way to notify everyone, [like] an Amber Alert? What is our system so we can get it out there?

“We were all left in the dark,” Meade said. “And that was the scariest thing.”

Los Angeles County officials did not respond to a request for comment.

The Ventura County sheriff’s department sent out three Wireless Emergency Alerts during the first hours of the Hill and Woolsey fires to various parts of the county, depending on what area was at greatest risk — first at 4:41 p.m. on Nov. 8 to the Camarillo and Thousand Oaks areas, then 11:26 that night to the Oak Park and Thousand Oaks areas, and then at 1:59 the next morning in the Westlake Village, Thousand Oaks, Sherwood and Hidden Valley areas.

Kevin McGowan, assistant director for the sheriff’s Office of Emergency Services, said Ventura County doesn’t have a way to confirm whether people received Wireless Emergency Alerts, but said he believes many people did receive them. The county also sent law enforcement to knock on doors and issued alerts through VC Alert, an alert system that can send out longer text messages and include links in them but requires residents to voluntarily provide their email addresses and phone numbers ahead of a disaster.

“You might not have received a message from every tool,” McGowan said, but added that if you heard about the evacuation order and left, then the effort was a success.

Some residents who were in mandatory evacuation areas told The Times they didn’t get an alert over their cellphones. Vanessa Christopher, 31, woke up at midnight on Nov. 9 to the sound of wind howling. It was only on Twitter that she first found out law enforcement had ordered the evacuation of her neighborhood in Thousand Oaks.

“This is kind of terrifying, but neither my husband nor I got emergency alerts to our phones,” she said.

Her neighbors later told her that police came by later to knock on doors to make sure everyone evacuated.

Serna and St. John reported from Paradise, Calif., and Lin from Los Angeles. Soumya Karlamangla and Sean Greene contributed from Thousand Oaks, and Nina Agrawal and Bettina Boxall from Los Angeles.

Twitter: @JosephSerna

Twitter: @paigestjohn