Lessons from disastrous wine country fires helped in battling Southern California infernos

Both sieges began in darkness with fierce winds that made the flames impossible to stop.

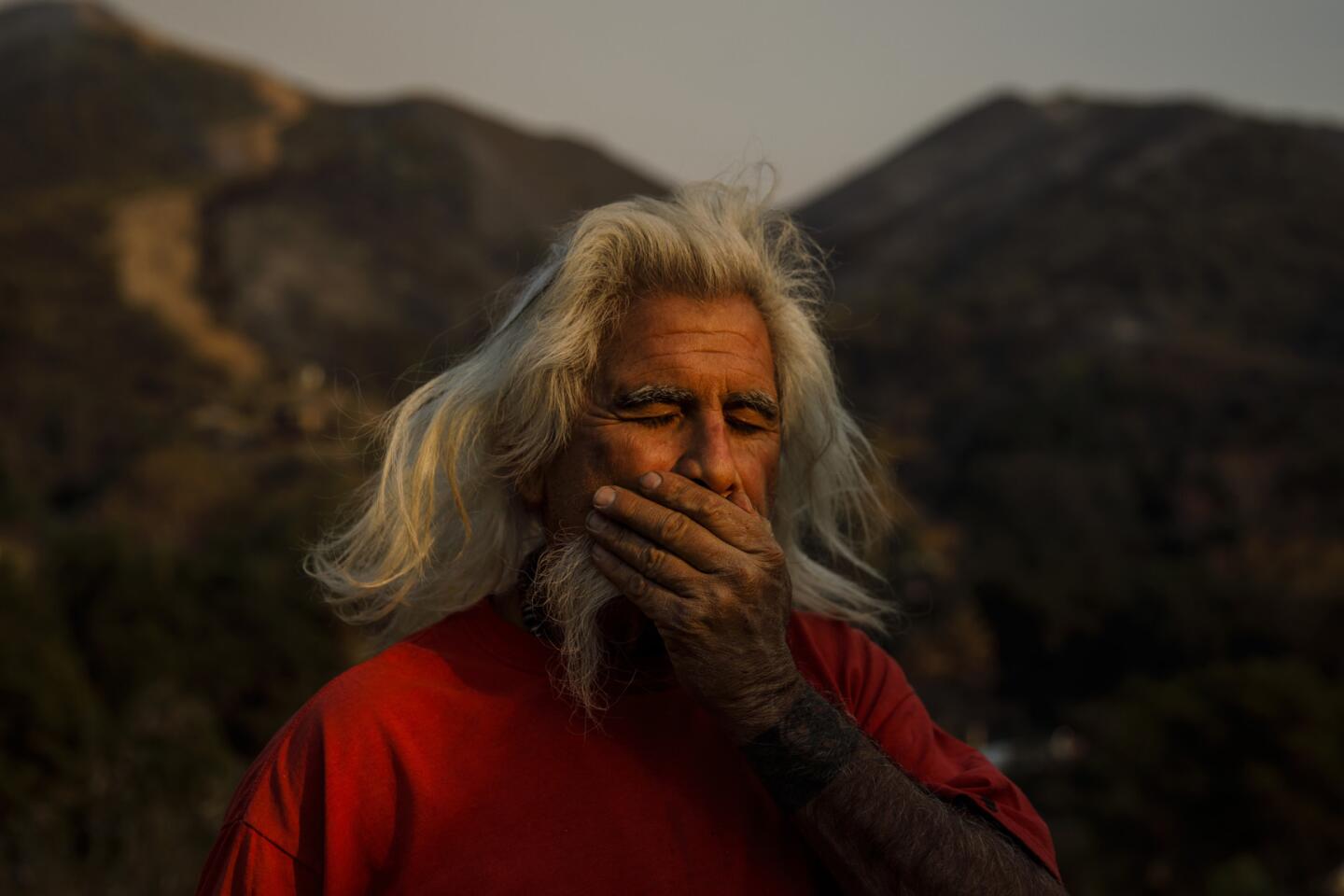

Hurricane-force gusts pushed the flames over highways that should have been barriers and into neighborhoods so quickly that officials said they were helpless to protect the homes in their path.

The wine country fires that ravaged Northern California in October and the firestorm in Southern California this month have capped the most destructive year for fires in state history.

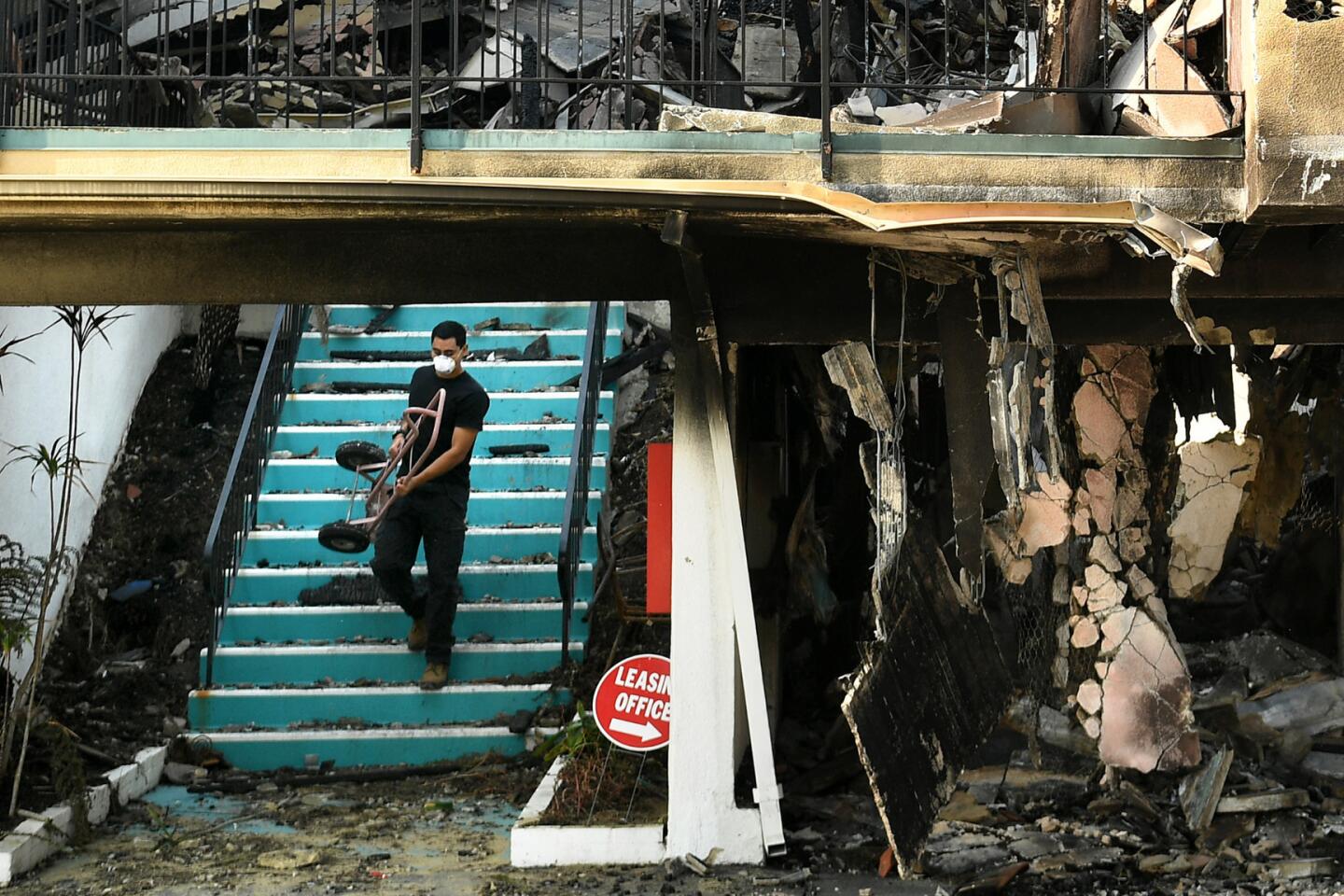

The wine country fires were far more destructive, killing 44 people and wiping out more than 10,000 homes. By contrast, the Southern California fires have destroyed about 1,000 homes and left two people dead, with the massive Thomas fire continuing to rage amid strong winds.

Southern California took key lessons from the disaster in the north. Issues that have caused so much debate since the wine country fires — a lack of communication and warnings, limited firefighting resources and the possible role of electric lines in sparking the blazes — were addressed in the early stages of the Southland fires.

GETTING THE WORD OUT

Aggressive alerts warned of dangers

In Northern California, there were fewer broad public warnings of the match-ready conditions.

In Mendocino County’s Redwood Valley, where nine people would die, a major vineyard owner went to sleep the night of the fire unaware of the hazardous conditions — only to wake up hours later in the midst of a panicked evacuation through mountain trails.

“Had he known, he could have turned the sprinklers on,” said Chris Boyd, a retired deputy fire marshal from Orange County who lives in Redwood Valley. The watered vineyard would have provided a safe spot to shelter in place.

Sonoma County has been the focus of sharp criticism for failing to use a federal alert system to loudly buzz cellphones and send alerts the night of the fire to wake those in jeopardy.

County officials have said they feared causing a broad panic that would gridlock evacuation routes. Similarly, in Mendocino County, sheriff’s officials said they held off evacuation orders until they could decide where it was safe to send fire refugees.

Both counties relied on messaging systems to which only a small fraction of residents subscribed, and which broke down when cell towers themselves fell to the blazes. Fire officials also repeatedly underestimated the speed of the fires, attempting to evacuate neighborhoods the blazes had already jumped while those in their path were without notice.

Aware of these problems, California state emergency officials decided last week to send unprecedented cellphone warnings to some 12 million residents in seven Southern California counties.

“We saw the potential for a similar firestorm to what we saw in Santa Rosa — the most severe part was going to be happening in the overnight hours when people were sleeping. That’s when people died,” said Kelly Huston, deputy director of crisis communications for the California Office of Emergency Services.

The warnings, which went out on a Wednesday, were timed to arrive at 8:30 p.m., after Southern California residents were home and settled but before they went to bed — with the idea of raising fire awareness so they would pay attention if local evacuation orders came. Huston said the broad alert was considered a success and will be added to the toolbox for future conditions.

San Diego-area resident Scott Butler said there were no fires within 50 miles when he got the alert, but by that Thursday his home in East Oceanside was under evacuation orders from the Lilac fire. “The early warning kept everyone vigilant,” he said.

GETTING TO THE SOURCE

Shutting off power lines

The Northern California fires began as falling trees brought down power lines and transformers blew. In addition to 14 fires large enough to be named, dispatchers reported the start of many more small blazes. The regional utility, Pacific Gas & Electric Co. turned off power to lines at the request of firefighters seeking access to blazes already in progress.

Though the cause of the Tubbs fire is still under investigation, numerous residents who lost homes have sued PG&E, saying that power lines downed by the winds sparked the blaze. PG&E has suggested the fire might have been caused by third-party power lines not owned by the utility.

When fires broke out Thursday in San Diego County, San Diego Gas & Electric Co. was proactive. It powered down lines in rural areas ahead of the blazes — catching criticism for preventing firefighters from tapping groundwater supplies because electric pumps were inoperable, but also preventing downed lines from igniting new spot fires like those in Northern California that sapped already-limited resources.

FIGHTING THE FLAMES

More resources, better prepared

Federal meteorologists placed both regions under red flag warnings for fire, triggered by forecasts of extremely low humidity and extremely high winds. In Northern California, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection put bulldozer crews on standby, but it did not pre-stage any firefighting resources. Instead, the agency sent a crew south to stand ready for blazes there.

As the wine country fires exploded, it quickly became clear the rural counties didn’t have the resources to put up a fight.

Throughout that first night, fire commanders sent out mutual aid requests for resources that weren’t available or had already been sent to neighboring counties that called for help first. It would take days for the state to send fire crews from across California. For the all-important first night, rural counties such as Mendocino relied primarily on volunteer fire departments that sent single engines or two.

On the ground, departments diverted precious resources to try to pin down reports of more fires, leaving stations bare. One firefighter grabbed an agency pickup truck, drove to the Redwood Valley fire and wound up fending off the flames with his mother’s garden hose. As the sun rose, he joined state troopers to look for bodies. Nine people had died.

Southern California simply has more resources at the ready, and it showed. The Thomas fire was the responsibility of the Ventura County Fire Department, with five battalions and more than 600 firefighters at the ready before mutual aid began to roll in. Ventura also had access to firefighters from the city and county of Los Angeles, as well as numerous suburban fire agencies.

By the third day of both fire sieges, the state had more than 2,700 firefighters on the ground. In Southern California, they were battling three fires covering some 70,000 acres. In Northern California, that same staffing was spread across 19 fires covering 328,000 acres.

DIFFERENCE OF SCOPE

14 wildfires at one time

Though both firestorms generated great attention, experts say the wine country blazes were worse for many reasons.

From a single sunset to sunrise in early October, 14 wildfires started across a seven-county area. The greatest death toll came from the Tubbs fire, which started on the outskirts of rural Calistoga and swept west down mountain valleys into suburban Santa Rosa. It ultimately decimated housing subdivisions that officials had thought safe from the reach of a wildland fire.

The Southern California fires kicked off in slower succession, taking a week to spawn half as many blazes and, after the first, providing area residents a clear idea of what to expect from the brittle-dry terrain and hot winds.

The Tubbs fire ignited at 9:45 p.m., but the Thomas fire in Ventura was reported at 6:23 p.m., growing slowly enough that firefighters were able to go door-to-door to move people out of a mobile home park in harm’s way. The difference in timing proved key to making people aware of the fires and getting them out of their homes.

“People are up, they’re paying attention, they’re aware … as opposed to waking up out of a dead sleep,” said Cal Fire spokesman Scott McLean.