Seismic Upgrade Plan Targets 80,000 Buildings : Quakes: But owners’ costs, which could run into the millions, pose significant obstacle to city program.

- Share via

Haunted by the possibility of a future earthquake far worse than the Northridge temblor, Los Angeles city officials are preparing a program of unparalleled dimensions for strengthening buildings--including 50,000 single-family homes.

But the cost--amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars, to be borne by businesses and households--presents a formidable political obstacle.

A package of ordinances to be submitted to the City Council in the coming months would call for retrofitting an estimated 80,000 residential and commercial buildings in a process that could last a decade or more. Supporters are convinced that such a program would someday save thousands of lives and billions of dollars.

Compliance with the standards would cost from $3,000 for a small single-family home to millions for a large commercial building.

Most of the suspect structures are in the older parts of the city south and east of the Santa Monica Mountains, and were spared the most violent shaking in the 6.7 Northridge earthquake of Jan. 17, 1994.

But because of the poor performance of several types of structures in recent earthquakes, engineers have concluded that thousands of buildings would fail during a large quake on a fault near Downtown--an event seismologists consider probable in the next 50 years, according to Richard Andrews, director of the California Office of Emergency Services.

The potential value of retrofitting was highlighted again last month when researchers at Stanford’s Risk Management Solutions raised their damage estimates for a 7.0 quake on the Inglewood-Newport fault to $145 billion with 8,000 deaths.

Los Angeles City Councilman Hal Bernson, who represents the west San Fernando Valley and is the city’s strongest seismic safety advocate, said he plans to push hard for adoption of the Building and Safety Department’s plan.

“We’ve seen what happened after Northridge,” Bernson said. “What if it was Downtown? There wouldn’t be a city left there. We’ve got to move forward.”

So far, deliberations on what to do about vulnerable buildings have been mainly technical, centering on how to codify complex seismic remedies.

In the next phase, building officials will face the more volatile task of deciding how hard they can push cash-strapped owners without touching off a political revolt.

The strategy taking shape combines voluntary and mandatory elements. Retrofitting would be mandatory to reduce the most urgent hazards--probably concrete buildings up to 17 stories and wood-frame apartments of two or more stories. For less dangerous buildings, the city is searching for funds to offer financial incentives, but would require retrofitting only when structures are sold or substantially improved.

Even limited mandatory retrofitting is likely to be opposed by many owners.

“If a building is built to code when it’s built, I think it’s pretty sad when they come back and say you have to do something to it,” said Dan Faller, president of the Apartment Assn. of Southern California. “They put themselves up as being gods and they want to protect us. We don’t need their protection.”

Elected officials are wary of forcing financial hardships on their constituents.

“You never know what’s going to happen when the council gets hold of it,” Bernson said. “I don’t know whether we’re going to do it all, but we’re sure going to give it our best shot.”

Councilman Richard Alarcon, who heads the city’s public safety committee, has convened a task force to seek financial help from the federal government, banks and insurance companies.

Without the incentives, Alarcon said, “some businesses could very well go out of business.”

But Alarcon conceded that all the help the city can get will not cover the need.

“I think that in all likelihood there will be a series of ordinances and that some of them will be initiated before the incentives are created, and some of them will be held off in order to put some incentives in place,” he said.

The city has already moved on the most startling and unexpected hazard highlighted by the Northridge quake by requiring owners to inspect steel-frame buildings and repair any damage. The buildings were long considered safe, but dozens were severely damaged in the temblor, raising the possibility of collapse in a larger quake. Although the repairs can cost several million dollars per building, they are considered “repairs,” not mandatory retrofitting.

Immediately after the Northridge earthquake, the city identified 2,100 pre-1976 concrete tilt-up buildings (made of concrete slabs that are poured on the ground and lifted into place) in need of mandatory retrofitting. But because of delays in processing, it has sent notices ordering the work only to about a third of those, according to Karl Deppe, assistant chief of the Department of Building and Safety’s building bureau.

Officials later recognized that tilt-ups erected after the 1976 code enhancements suffered similar problems; the city is seeking mandatory retrofitting for an unknown number of additional structures.

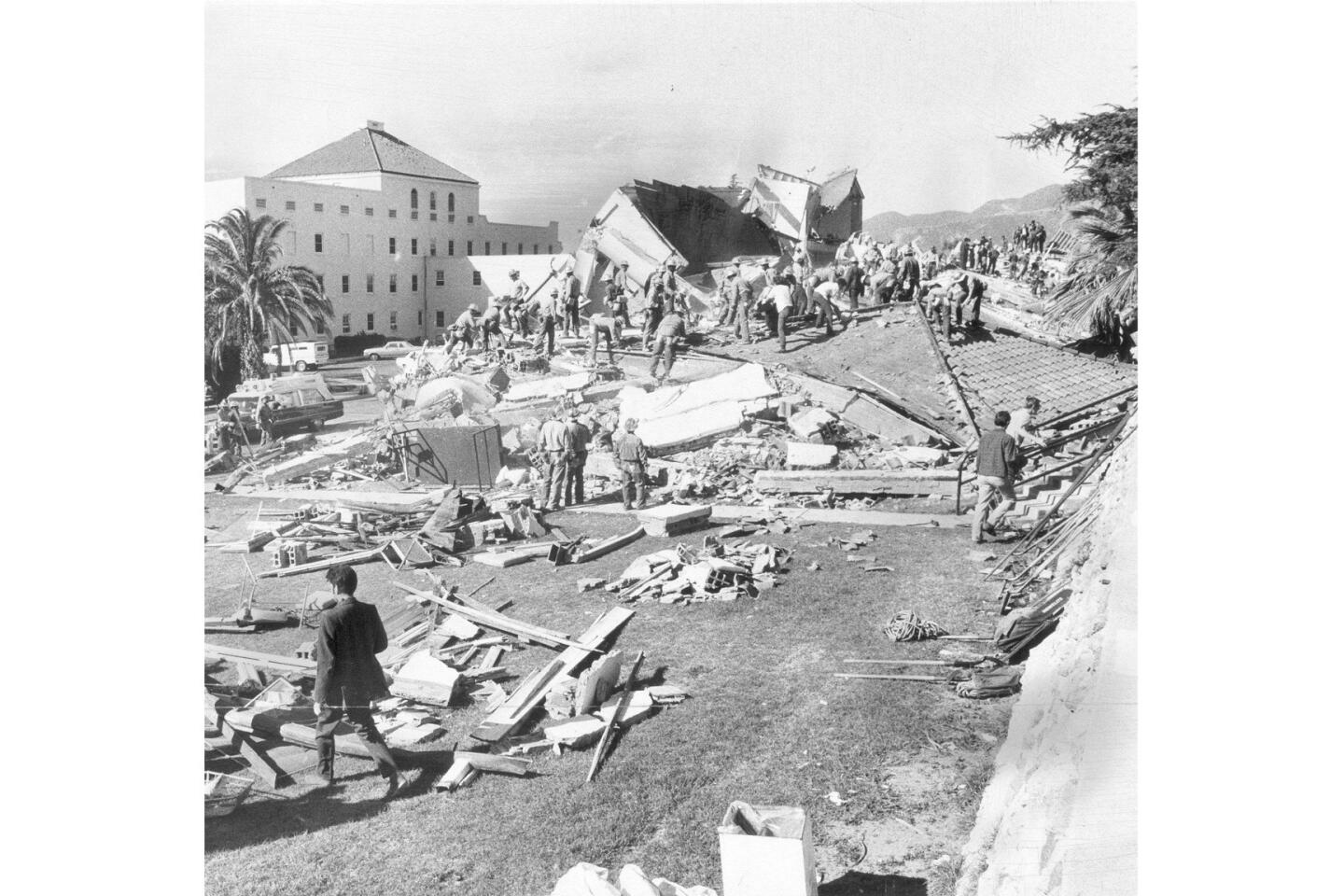

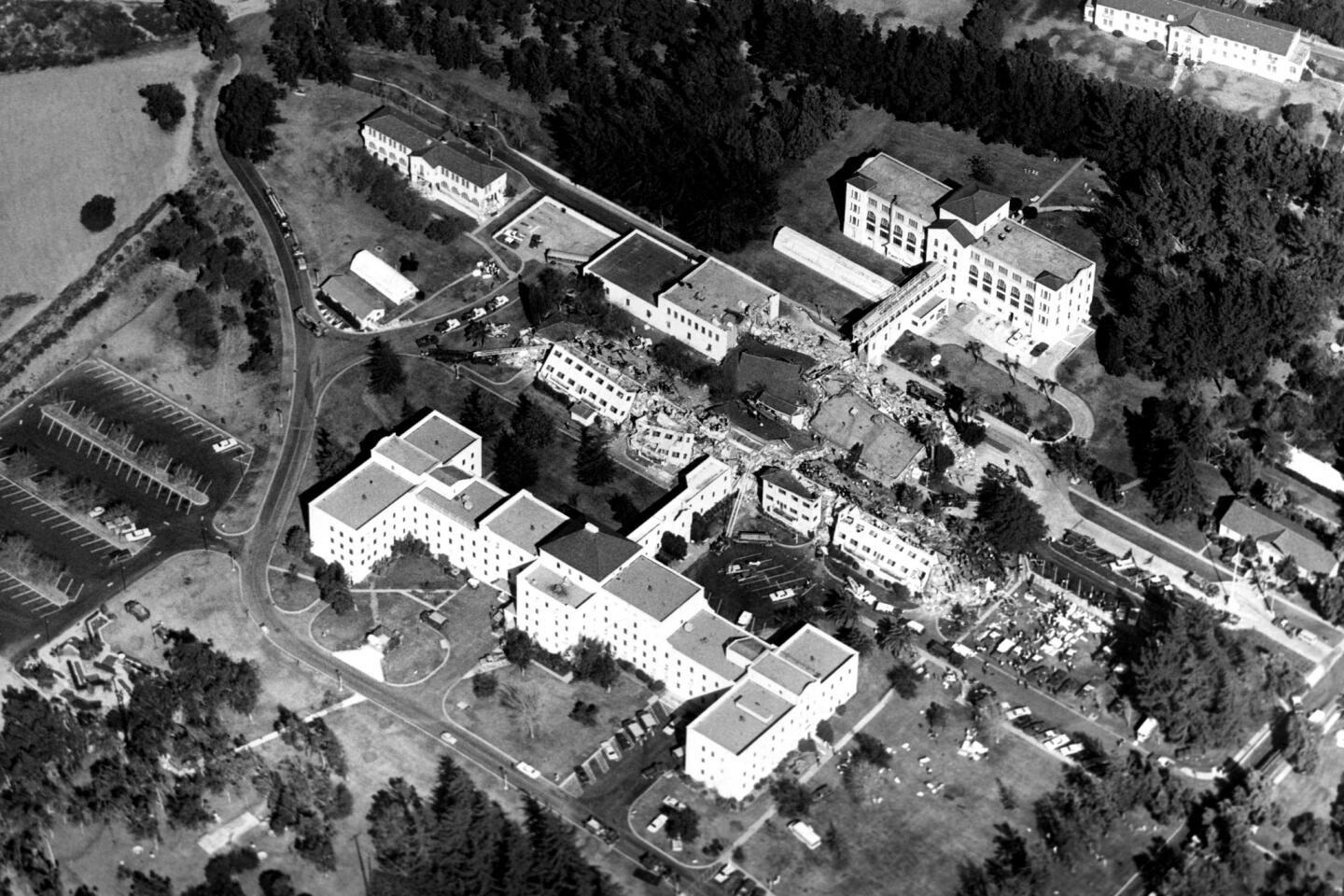

Los Angeles’ only previous experience with seismic retrofitting resulted in the strengthening or demolition of about 7,700 unreinforced masonry buildings, whose life-threatening weakness was exposed by the 6.4 Sylmar earthquake in 1971, which killed 58 people.

The unreinforced masonry retrofitting cost $4 to $12 per square foot, borne entirely by the owners. It was credited with saving hundreds of lives in the 1994 Northridge quake, which killed 57 people. Dozens of buildings cracked or shifted, but did not collapse, as they probably would have without the added reinforcement.

But the program also left a residue of resentment among building owners, who felt that retroactively imposing new, costly standards was unfair.

Building officials now think they have no option but to impose yet more standards because of the unexpectedly poor performance of several types of buildings in the Northridge earthquake. Besides covering about 1,200 older concrete buildings and about 20,000 apartments, the proposals would apply to more than 1,000 concrete tilt-up buildings, about 7,000 hillside dwellings and 50,000 older single-family houses.

The extraordinary scope of the proposals taking shape reflects the fact that officials are for the first time attempting to limit the cost of massive disaster repairs, as well as protect lives.

The goals have been endorsed at the state and federal levels, but they must be put into effect by local elected officials--who weigh potential savings in a future disaster against the present cost to their constituents.

As a prime example of the benefits of the new approach, building officials cite the historic homes in the 6000 block of Selma Avenue, near Gower Street, in Hollywood.

In mid-1993, homeowner Billy Martin paid a contractor $3,500 to strengthen his bungalow. It came through the earthquake undamaged except for the chimney, which had to be replaced. Twenty other houses on the block were seriously damaged, including eight that were torn from their foundations. Building permits reflect a blockwide damage estimate of almost $1 million. Two homes were demolished and rebuilt at a cost of about $150,000 each.

Seismic safety officials have begun to take a critical look at the immense public resources that must be spent to repair damage that could have been prevented for a fraction of the cost.

Such examples led the California Seismic Safety Commission to urge the introduction of “performance standards”--calculations on the amount of shaking a building could sustain without damage--into building codes that historically dealt only with “life-safety” standards.

Performance standards are particularly applicable to wood buildings such as apartments and the estimated 50,000 older single-family houses with subfloor crawl spaces. The short walls, called cripple walls, that hold the house off the foundation can collapse in an earthquake, causing serious destruction, but not usually endangering occupants.

The older houses can be strengthened to standards being prepared by the city for $3,000 to $5,000 per house, or $10,000 to $15,000 if the foundation is weak. Retrofitting hillside houses, complicated by multilevel foundations and taller cripple walls, would cost about $7,000 to $15,000, city officials believe.

At one time, building officials considered mandatory retrofitting for single-family homes, but eventually rejected it because the cost would most often fall on middle- or low-income families, Deppe said.

In a recent interview, James Lee Witt, director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, added his support to damage-reduction measures, proposing a national hazard-mitigation trust that would be funded by a percentage of the agency’s annual $320-million disaster appropriation.

In the meantime, local officials have only meager FEMA resources available to stimulate voluntary retrofitting.

In the absence of federal assistance, city officials are asking insurance companies, banks and the federal government to help in a long-range effort to induce homeowners to make the improvements.

The city has obtained a $750,000 FEMA grant, and is spending $250,000 of its own, to retrofit 50 houses yet to be selected across the city, and to inspect 500 others. The inspections will be used to devise an earthquake-worthiness rating system. City officials will urge insurance companies to offer premium reductions for safer houses, creating an incentive for doing the work, Deppe said.

As a last resort, the city plans to propose mandatory retrofitting of other houses when they are sold or when at least 30% of the house is remodeled.

“Why can’t we encourage the banks, instead of loaning $80,000, to loan $84,000 and just do it?” Deppe asked.

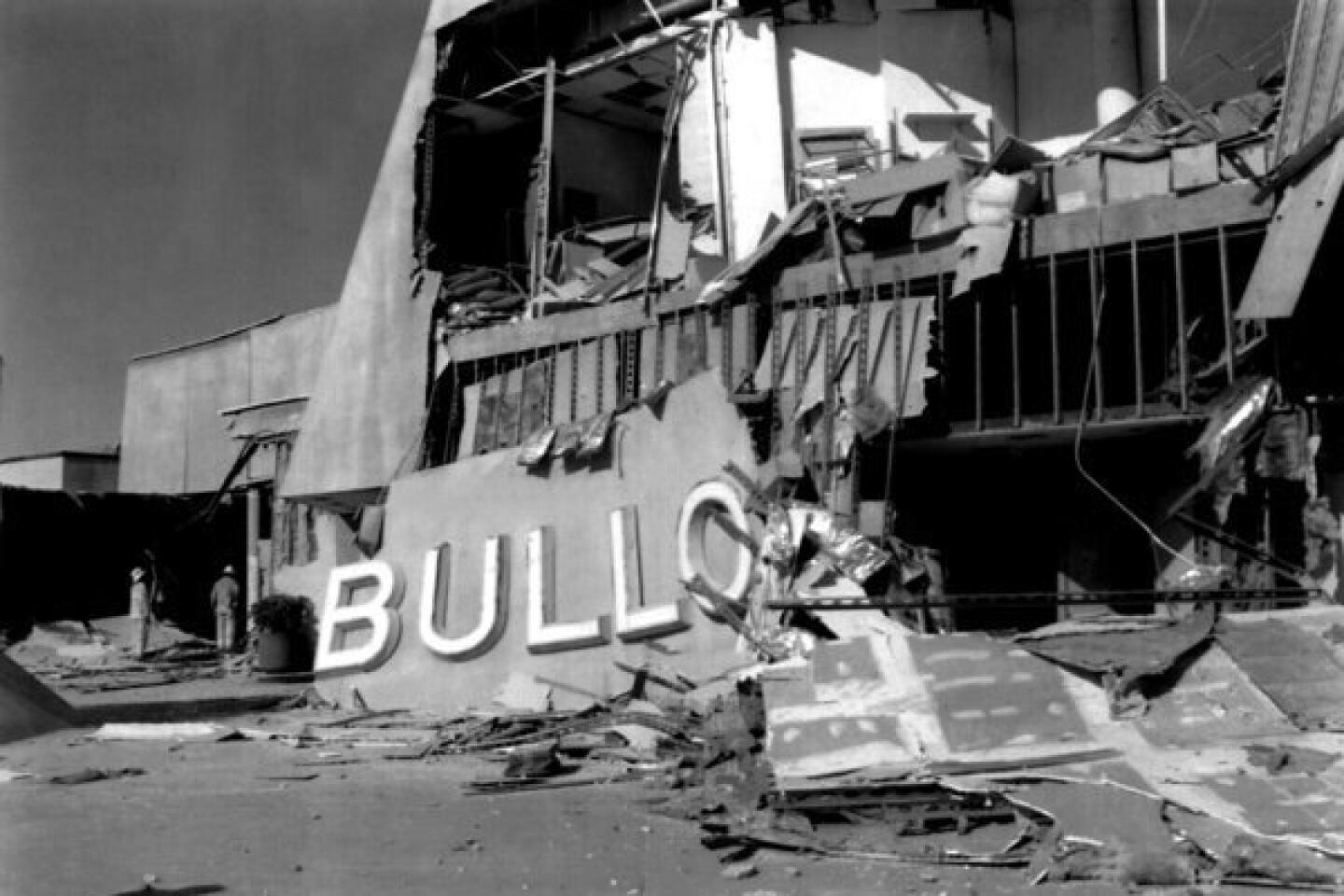

The first to feel the bite may be the owners of about 1,200 older concrete buildings such as mid-rise offices, enclosed malls, parking structures and hotels.

Especially shocked by the failure of concrete buildings during the earthquake in Kobe, Japan, Los Angeles officials consider them the city’s most unsafe. Two such structures--a West Los Angeles office building and a Kaiser Permanente medical office in Panorama City--were condemned immediately after the Northridge temblor.

Also targeted for mandatory retrofits are masonry buildings constructed after 1976. Although code changes inspired by the Sylmar quake required reinforcement of new masonry buildings, the Northridge quake proved the new standards were inadequate, Deppe said.

It may be difficult to persuade the City Council to push ahead with mandatory measures, Deppe said, because the owners of many of these buildings, especially in Downtown, are already financially strapped.

The most volatile proposal probably will be for mandatory retrofitting of an estimated 20,000 multistory wood-frame apartment houses like the Northridge Meadows complex, which collapsed in the quake, killing 16 people.

The method of strengthening involves removal of either the exterior stucco or interior drywall and installation of a sheath of plywood. The cost ranges from $2,500 to $5,000 per apartment unit, engineers estimate.

Deppe said the city plans to deal first with the most vulnerable apartment houses--those with open parking spaces under part of the first floor.

Whatever Los Angeles ultimately does, it is not likely that other cities and counties will quickly follow suit, said Fred Turner, staff structural engineer of the California Seismic Safety Commission.

Historically, mandatory retrofitting has been slow to take hold across the state.

About half the unreinforced masonry buildings outside Los Angeles have yet to be retrofitted. And in 1990, then-Gov. George Deukmejian, under pressure from the real estate industry, vetoed legislation that would have required retrofitting of single-family houses when they were sold.

Turner said he sees no prospect for reviving that proposal.