Property Owners May Be Forced to Retrofit : Quakes: Plan could affect 100,000 homes, apartment buildings. If mandatory, city would include financial aid.

- Share via

Aiming to lessen residential damage in future earthquakes, Los Angeles city building officials are proposing a massive and costly program that could require thousands of owners to strengthen their wood-frame houses and apartment buildings.

Building officials are considering whether the retrofitting program--potentially the most extensive ever undertaken in the city--should be mandatory.

If a mandatory program is chosen, it would include financial assistance to ease the burden on property owners, who could be required to beef up foundations and walls at costs ranging from $1,000 to $18,000 per structure.

The plan, which officials say could affect 100,000 or more structures, is expected to spark debate when submitted to the City Council for approval early next year.

Pre-1950 houses with horizontal wood siding and those with inadequate foundation bolting are particularly vulnerable to quakes, building officials said. Newer homes can also be at risk if stucco provides their only form of seismic bracing.

Officials are debating the politically volatile question of how to get full compliance without making unacceptable financial demands on homeowners, particularly those in older neighborhoods. One option under consideration would require seismic upgrades only when a house changes hands.

An early staff proposal for mandatory retrofitting was sent back for revisions by top building officials who insisted on an accompanying package of financial aid.

“We don’t think a lot of these homeowners have the money and we don’t want to chase them out of their homes,” said Karl C. Deppe, chief of the Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety’s building bureau.

The proposal for retrofitting of dwellings is part of a comprehensive seismic safety program developed by the department after the Jan. 17 earthquake.

Building officials outlined the plan Saturday at a conference of the Structural Engineers Assn. of Southern California.

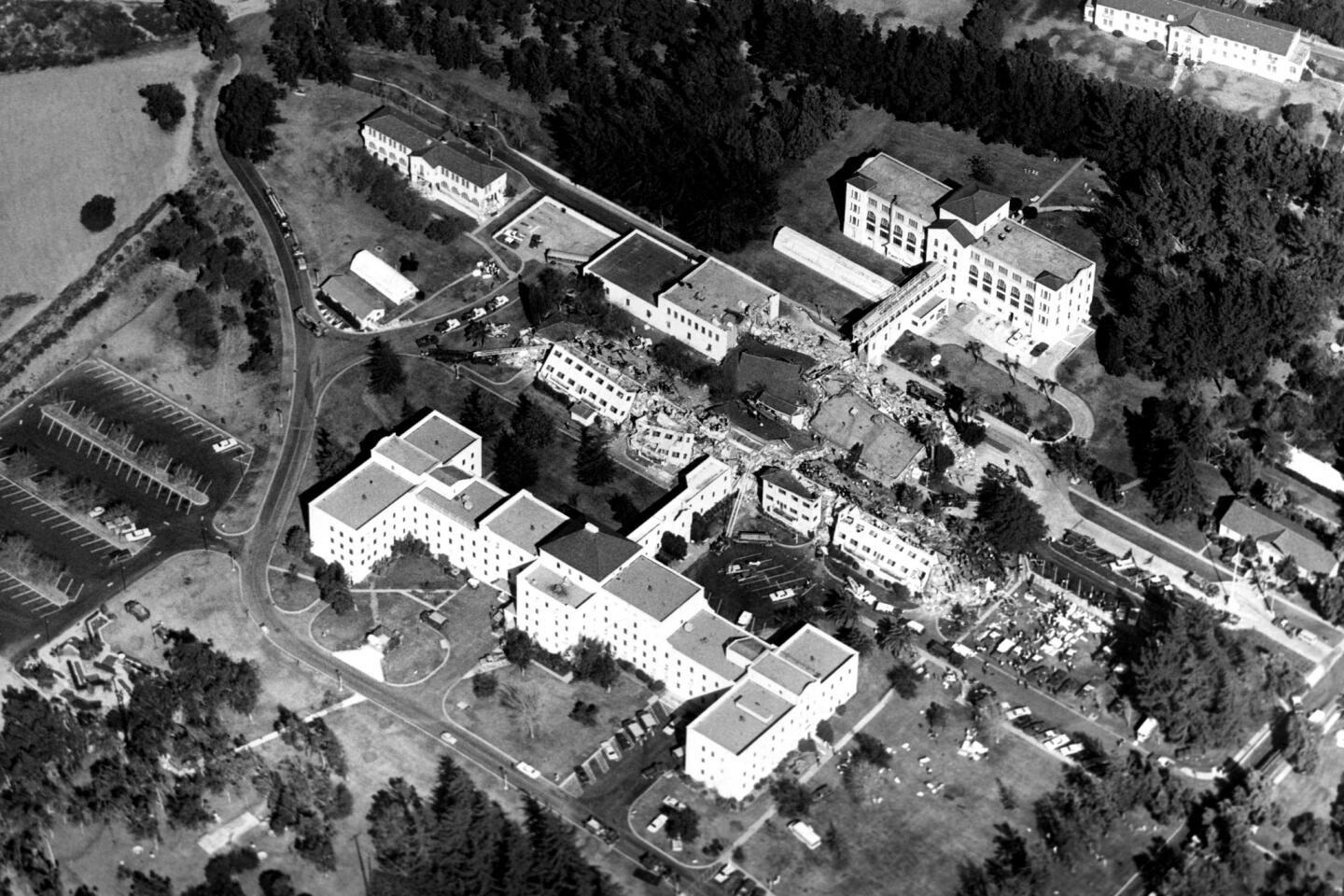

The officials told about 500 engineers that the Northridge earthquake, far exceeding any other American disaster in property damage, was only a “near miss” for flexible-frame buildings outside the Valley and Westside, where its force was strongest.

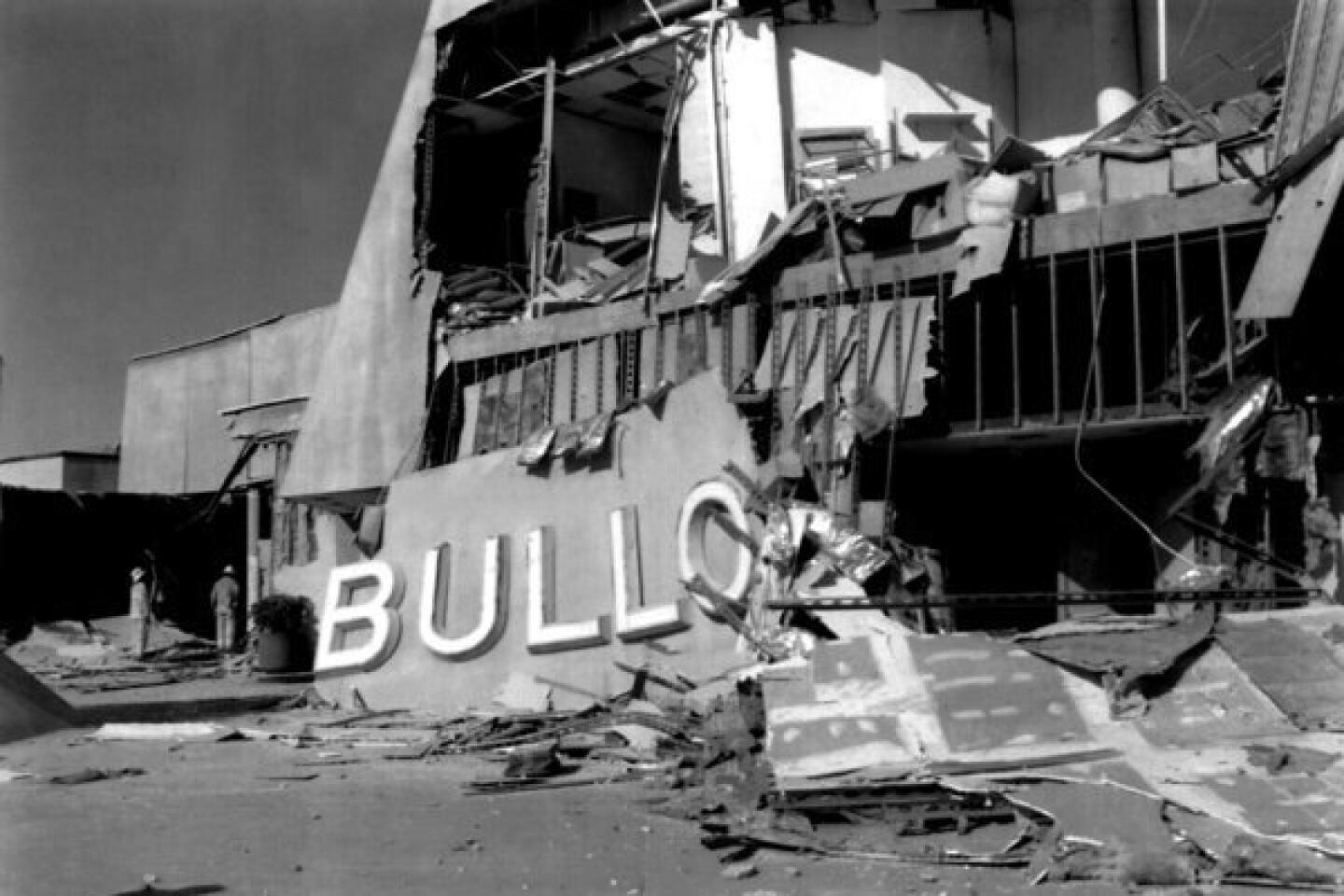

Rick Ranous, senior structural engineer with the California Office of Emergency Services, said the relatively low death toll showed that the building code is adequate to protect human life--its primary purpose. But he said the estimated $17 billion that will be spent repairing damaged structures is not acceptable.

“I think now is the time we need to start looking at our building code in terms of property protection, not so much for the individual property owners, but for the taxpayers of California and the country as a whole,” Ranous said.

The city’s wood-frame house proposal is designed to minimize public and private expense from future quakes. It “would reduce the number of uninhabitable homes and avoid the increased public assistance costs to repair damage and provide temporary housing after future earthquakes,” according to the plan’s report, prepared by a committee of building officials and seismic consultants.

Repair costs for wood-frame buildings damaged in the Northridge earthquake have been estimated at more than $2 billion.

The building department is developing recommendations that would cover new construction and standards for retrofitting all types of structures, including wood-frame houses and apartments, steel-frame office buildings and concrete structures. These include building code changes to ensure that new structures are more earthquake-safe, and they call for mandatory seismic strengthening of hundreds of existing steel and concrete buildings.

The current recommendations for wood-frame homes do not cover hillside dwellings, described by a review committee as posing “the greatest life safety risk of any damaged dwelling (type) investigated.” A set of more exacting retrofit standards is being drawn up for hillside houses with multilevel foundations.

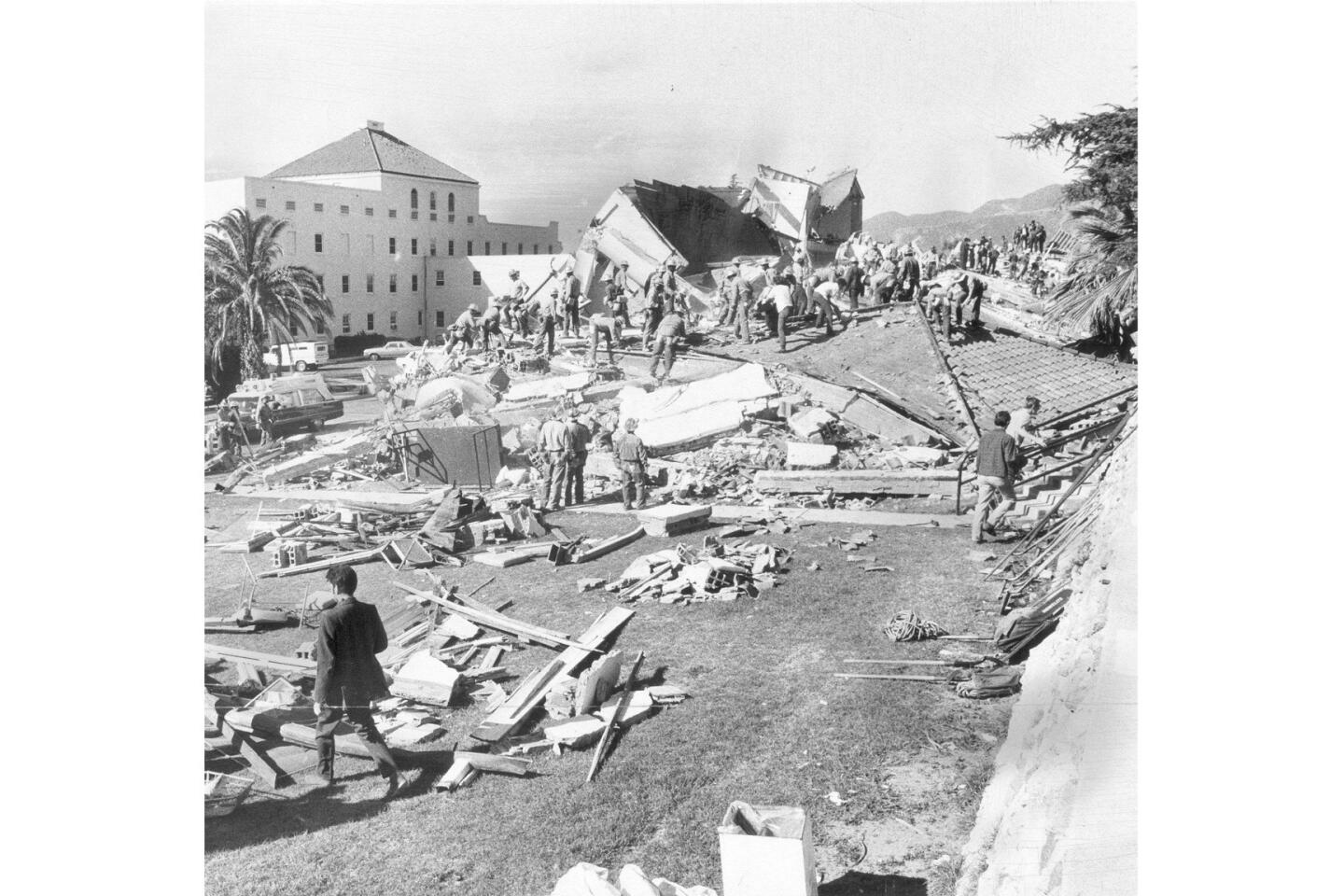

Although the strengthening of steel-frame and concrete buildings will prove the costliest earthquake programs, officials said the numbers of wood-frame buildings that need work would dwarf any retrofitting program in the city, including the repair of more than 8,000 unreinforced masonry buildings after the 1971 Sylmar earthquake.

Officials said there are many thousands of homes with unbolted foundation plates, foundations of inferior quality materials and poorly braced cripple walls--the short wall holding the floor off the foundation.

Although older houses are most vulnerable, inspectors found “serious damage was very common in houses of all ages where stucco was the only bracing material.”

“Locating and inventorying buildings with these characteristics would be necessary to determine the true scale of a mandatory retrofit program,” the report said.

Finding all the houses that need retrofitting, much less mounting an inspection program, will be a daunting job, Deppe said. “That would start with our automated records and go from there,” he said. “You really have to go out and look at every building.”

In examining hundreds of damaged wood-frame structures, inspectors found that the stucco either cracked under stress or separated from the wood framing, negating its seismic-bearing strength.

Houses with crawl spaces commonly had failures of the short wall holding the first floor off the foundation or separation of the house from the foundation because of inadequate hold-down straps or bolts.

Even houses built on concrete slabs are vulnerable to foundation failures because of the practice of pouring the foundation first and the slab later. Apparently, sand spread under the slab often spills onto the foundation, preventing bonding of the joint, officials said. Also, the bolts that hold the house down often extend only into the slab, not into the foundation.

To solve those problems in new construction, the committee is recommending tougher rules for bracing walls and bolting down foundation sills--wooden plates where wall studs are attached--and new procedures to improve the bonding of foundation and slab.

For existing houses with defects, the remedies include removing stucco and backing it with plywood, installing additional sill bolts or straps by drilling into the foundation, and reinforcing the bracing of the short walls between the foundation and floor.

In most cases, building officials said, the cost for the repairs would range from $2,000 to $4,000, but could go as high as $18,000 on large houses in which access to the work area is restricted.

Building officials believe that homeowners who make relatively inexpensive repairs could save themselves huge losses in a future earthquake striking closer to Downtown Los Angeles.

“The city is going to have to take a stand on hazard mitigation related to earthquakes,” said Nicolino Delli Quadri, chief of the building department’s training and emergency management division. “What are we going to do? We can’t just ignore it.”

Hoping to defuse potential opposition from homeowners who cannot afford such work, building officials are soliciting state and federal agencies and the private sector to come up with solutions.

Deppe said he is working with bankers and insurance executives on Mayor Richard Riordan’s blue ribbon panel on hazard reduction to develop a package of financial incentives that could lessen the burden.

Among the ideas being pursued are insurance rate breaks for retrofitted houses and allowances to add repair costs to the new loan when a house is sold. Federal and state tax deductions or credits also are being explored.

While the debate goes on, building department staff members worry that those who voluntarily upgrade their houses may not have the city guidance now to do it right.

“What are they going to retrofit to?” asked Delli Quadri. “We don’t have a standard to hold them to.”