California’s broken charter school law has defied reform. Can Newsom break the gridlock?

California is home to about one out of every five charter schools in the United States, but state oversight of them is far from a national model.

Since the Charter Schools Act of 1992 was passed more than a quarter-century ago, a political standoff in Sacramento has made it almost impossible to repair even the parts of the charter law that no one disputes are broken.

Even though Democrats have a firm grip on the Legislature, they are not united on charter schools. Torn between allegiances to pro-charter philanthropists and the powerful teachers union, lawmakers have for years begun each legislative session by introducing a handful of bills favorable to one side or the other. Many have died in committee. Those that have made it to a governor’s desk often have been vetoed.

With the arrival of Gov. Gavin Newsom, there are signs that the gridlock is ending.

Part 1: How a couple worked charter school regulations to make millions

Part 2: Small districts reap big profits by approving charter schools with little oversight

Shortly after he was sworn in, Newsom instructed lawmakers to fast-track charter legislation that politicians had been arguing over for years. The law he signed earlier this month makes charter schools subject to the same public records, open meeting and conflict-of-interest laws that apply to traditional public schools.

“Leadership matters. Who is at the top matters,” said state Sen. Connie Leyva (D-

How far Newsom will go to tighten regulation of charters remains to be seen, however — and there’s reason to be cautious in predicting legislative support.

For 27 years, the teachers union and pro-charter advocates have been fighting a custody battle over California’s public schoolchildren and the state funding that follows them.

Although the California Teachers Assn. and the California Charter Schools Assn. insist that they are willing to negotiate with each other, there has been scant evidence of cooperation. Both organizations have spent millions to sway public opinion far beyond Sacramento. In charter-packed L.A. and Oakland, school board elections have become proxy wars.

The result mostly has been policy paralysis. With the exception of a few tweaks around the edges, charters’ regulatory framework has remained frozen in amber — a reflection of ideas that made sense more than two decades ago, when the schools were new and rare.

The two sides have rejected even each others’ most modest suggestions for change. At times, each has pushed aggressive measures wholly unacceptable to the other when compromise might have been possible.

Neither has fought for the kind of change that experts say could be most meaningful — stronger regulations that are already in place in many other states.

“There’s been almost no political action to think about how we can do this better,” said UCLA education professor John Rogers.

Of the 44 states that have charter school laws on the books, at least half have enacted quality control measures that don’t exist in California, according to a recent analysis by Harvard University researchers.

Many states hold authorizers to a set of performance standards. Some sanction authorizers or don’t let them approve new schools if they are negligent, sponsor charters with poor track records or try to block every applicant.

Six states and Washington, D.C., have created independent chartering boards on the theory that forcing state education agencies to act as authorizers distracts them from their main jobs and often leads to weak oversight.

“The good news, and frustrating news, is we know how to do this. You can go to places and see good authorizing. It’s not like we’re trying to put a person on Saturn,” said Greg Richmond, president and CEO of the National Assn. of Charter School Authorizers, citing New York, Washington and Boston as examples of success.

As the founder of a nonprofit that helps launch new charter schools, Dirk Tillotson knows the problems with California’s charter law.

Tillotson has spent more than 20 years bouncing between Oakland and New York City, where he helped open 17 charter schools. Both cities have experienced astonishing charter booms, which have been followed by backlashes led by progressives alarmed by the influence of ultra-wealthy charter school backers.

New York, Tillotson said, is a far better place to open a charter school, and not just because state funding is more generous.

Rather than deputizing every school district to approve, deny and supervise charters, New York reserves that job primarily for the State Board of Regents and the State University of New York Board of Trustees. Though neither of the institutions can claim to be completely impervious to shifting political winds, they have developed expertise, consistent methods and scale.

“New York is much better than here because there’s predictability,” Tillotson said. “There’s a set of standards that are relatively equally applied across the board.... But in California, the politics of it make it a crapshoot. Here, it’s the Wild West.”

Over the years, study after study has come to a similar conclusion — that California’s system of charter authorizers needs an overhaul.

Fifteen years ago, in 2004, the Legislative Analyst’s Office called for the Legislature to build checks and balances into the process by creating basic criteria for authorizers and empowering the state to bar those that failed to meet those standards from future charter supervision.

In 2010, the nonpartisan Little Hoover Commission called the system “dysfunctional” and urged lawmakers to assign charter-oversight duties to an independent state commission.

In 2016, the National Assn. of Charter School Authorizers, in a report on California’s law, said that the state allowed far too many authorizing bodies.

“There are some advantages to local oversight, including direct familiarity with student needs and relationships with social services,” the association said. “But the current policy has produced a crazy quilt of charter oversight characterized by extreme variances in authorizing attitudes, practices, and quality from one district to the next.”

Neither the state’s labor unions nor charter proponents have been eager to embrace — and push legislators to embrace — the prescriptions for how to solve these well-documented problems.

The problem is that making changes requires those who have certain powers and freedoms to be willing to give them up.

The California Teachers Assn. has opposed the rapid expansion of charter schools, which are mostly not unionized. But if those schools keep multiplying, then the union would prefer keeping regulatory authority at the local level, where the association has been able to forge relationships with and help elect school board leaders.

As a result, the teachers union has become a defender of local control, arguing that school districts are the best gatekeepers of charter schools and that they need more power to make decisions, not less.

“We believe that charter schools should be authorized by local school boards. Those are the ones accountable to the voters,” said California Teachers Assn. President Eric Heins. To those who argue that local control leads to inconsistent regulation, Heins says: “It’s like saying democracy is chaotic. Well yeah, but democracy is the best system we have.”

The argument for local control resonates in districts like Oakland, where about 26% of the 50,000 students enrolled in charter schools last year, and Inglewood, where 29% did. Students leaving their local schools for charters have helped push those already financially struggling districts to the brink of fiscal crisis, and have led to calls for a moratorium on new charters. Without such a step, supporters say, the districts will never recover financially or academically.

Lawmakers aligned with the union have repeatedly proposed legislation to allow districts to reject charters if they pose a “financial hardship” to traditional public schools. They also have argued for reducing appeals, giving districts final say on most charter petitions.

Many charter supporters, however, say that a system that allows school districts to authorize charter schools is like putting the taxi industry in charge of regulating Uber and Lyft. Because school districts view charter schools as competition, they argue, they have an inherent conflict of interest.

“There was supposed to be a dynamic tension, and a certain amount of it is healthy and good,” said Myrna Castrejón, president and CEO of the California Charter Schools Assn. “But often in a highly politicized environment, without clear guardrails, it can really easily devolve.”

Some in the pro-charter movement suggest that it would be better to create a system that left charter authorization decisions to county boards, which are not direct competitors. But others counter that charter school proponents would then just try to stack the county boards of education with pro-charter people.

Former state Sen. Gary Hart, the author of the original charter school law, said in an interview that after the 1992 law passed, he quickly realized that it was wrong to assume that school board members would have the time and inclination to monitor charter schools properly. He still believes that districts should play a role but now tends to think that California needs authorizers insulated from day-to-day politics.

“If I had to do it all over again, I’m not sure granting chartering authority to school boards makes a lot of sense,” he said. “It was a little bit of a pipe dream.”

Newsom was not many charter advocates’ favorite candidate for governor.

Though he was supportive of charter schools as mayor of San Francisco, he did not share Gov. Brown’s personal connection as a former charter school founder. On the campaign trail, Newsom was endorsed by the California Teachers Assn. and called for a moratorium on new charters. Also, charter supporters spent $23 million in the gubernatorial primary to try to elect former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa.

But Newsom’s election isn’t the only reason those who want to change the charter law now see opportunity.

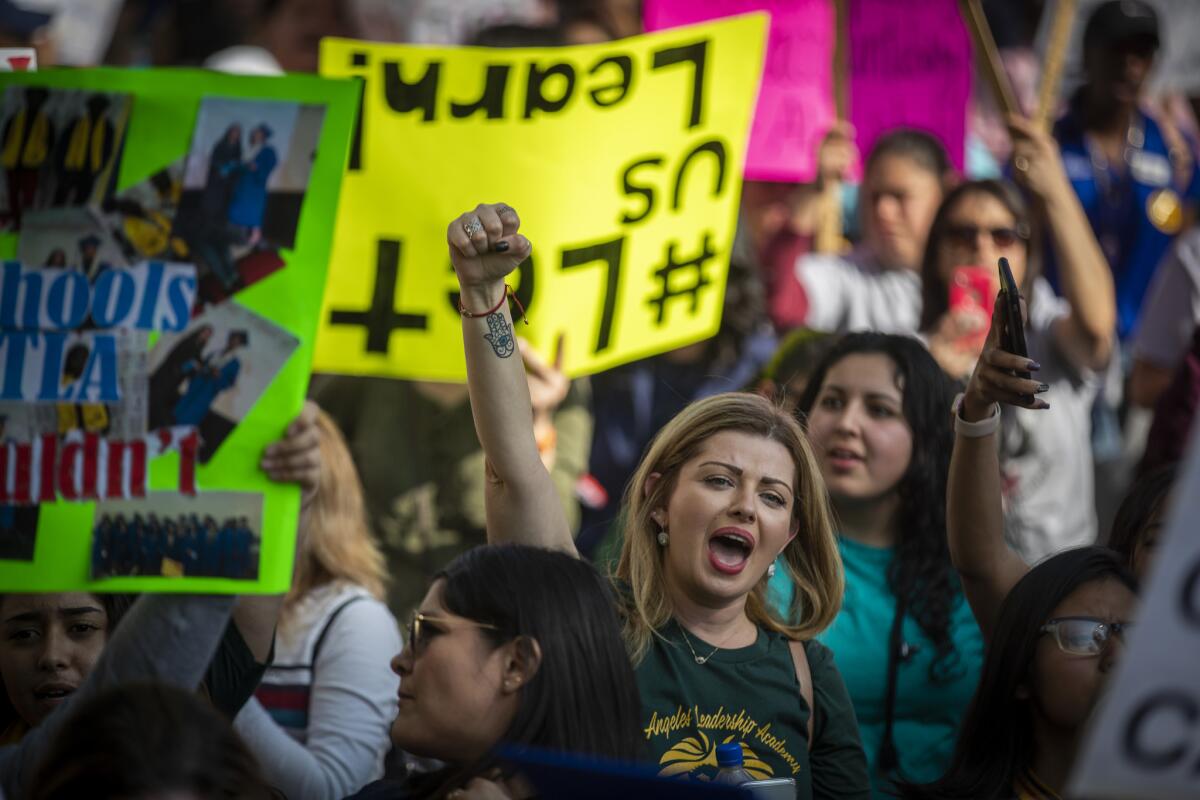

He’d been in office just about a week when L.A. teachers staged their first strike in 30 years.

In the national spotlight, they called for higher pay, smaller class sizes, more funding for public education. They also spoke out forcefully about charters — schooling the public about the financial consequences when charter schools woo away traditional public school students and the funding that goes with them.

The teachers union asked for a cap on new charters. It asked for tougher regulation.

After the strike ended, the L.A. school board voted to call for a temporary moratorium on new charter schools in the district while it studies their effects on traditional schools.

The next month, striking Oakland teachers won a pledge from their district to put opening new charters on pause.

Even if Newsom’s preference might have been to push off charter school issues in favor of other projects, Rogers said, “he doesn’t have the luxury of not attending to it because of the political dynamics.”

Charter advocates know they’re on shaky ground. They have tried to ally themselves with striking teachers’ calls for more public school funding, while rejecting the premise that charters contribute to district schools’ money woes.

Meanwhile, a package of union-friendly bills that would cap charter school growth, restrict charters’ right to appeal and allow districts more latitude to reject their petitions has been introduced in the statehouse. Other proposed legislation would bar charters from opening schools outside their authorizing districts.

These combined proposals would have the effect of concentrating power in the hands of school districts. Castrejón claimed they would force the closure of the majority of charter schools within five years. “To me, that seems like their end goal,” she said.

California lawmakers could, of course, remain paralyzed, trapped between opposing sides, fearful of incurring either the unions’ or the charter backers’ wrath.

The system could default to doing what it has done in the past: addressing peripheral issues and leaving the core problems in the charter law unresolved.

Last summer, former Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson convened a panel of experts to consider ways to improve the law. The group disbanded without agreeing on a set of recommendations.

Newsom has requested a new task force to study the fiscal impact of charter schools on school districts. It’s supposed to report back in July.

Twitter: @annamphillips