Santa Barbara County knew mudslides were a risk. It did little to stop them

During severe winter storms, Cold Springs Creek above Montecito turns into a torrent of mud, uprooted trees and shed-size boulders as it drains three square miles of sheer mountain front.

The only thing protecting the people, homes and businesses below is a low dam that the Army Corps of Engineers built in 1964 at the mouth of the creek’s canyon, forming a basin between the steep banks to catch the crashing debris.

Over the decades, the basin filled up with sediment and grew thick with brush and trees.

Over the years the Cold Springs Creek basin has repeated a cycle of filling and cleaning. By 2017, the basin was almost unrecognizable. (Google maps, UC Santa Barbara Library)

Few officials gave much thought to the condition of the old structure — or to that of the 16 other basins built along the mountains’ edge from Santa Barbara to Carpinteria — until the Thomas fire last December left the slopes bare and vulnerable to rapid erosion. On Jan. 9, a storm unleashed mudslides that ravaged Montecito, killing 23 people, destroying 130 homes and causing hundreds of millions in damage.

An eight-month Times investigation found that government officials did not heed decades-old warnings to build bigger basins that could have made the mudslides far less catastrophic — and that Santa Barbara County failed to thoroughly empty the existing basins before the disaster, drastically reducing their capacity to trap debris.

County flood control officials and the Army Corps had known for half a century that there were too few catchments and that the ones they had were far too small to stop the enormous debris flows that the Santa Ynez Mountains were prone to produce.

In 1969, the Corps’ district engineer for the region, Col. Norman E. Pehrson, issued a dire warning to the county about the Montecito area.

“The danger of loss of life and the menace of public health is great,” said a memo summarizing Pehrson’s conclusions five years after the Cold Springs Creek basin and five others were built in 1964.

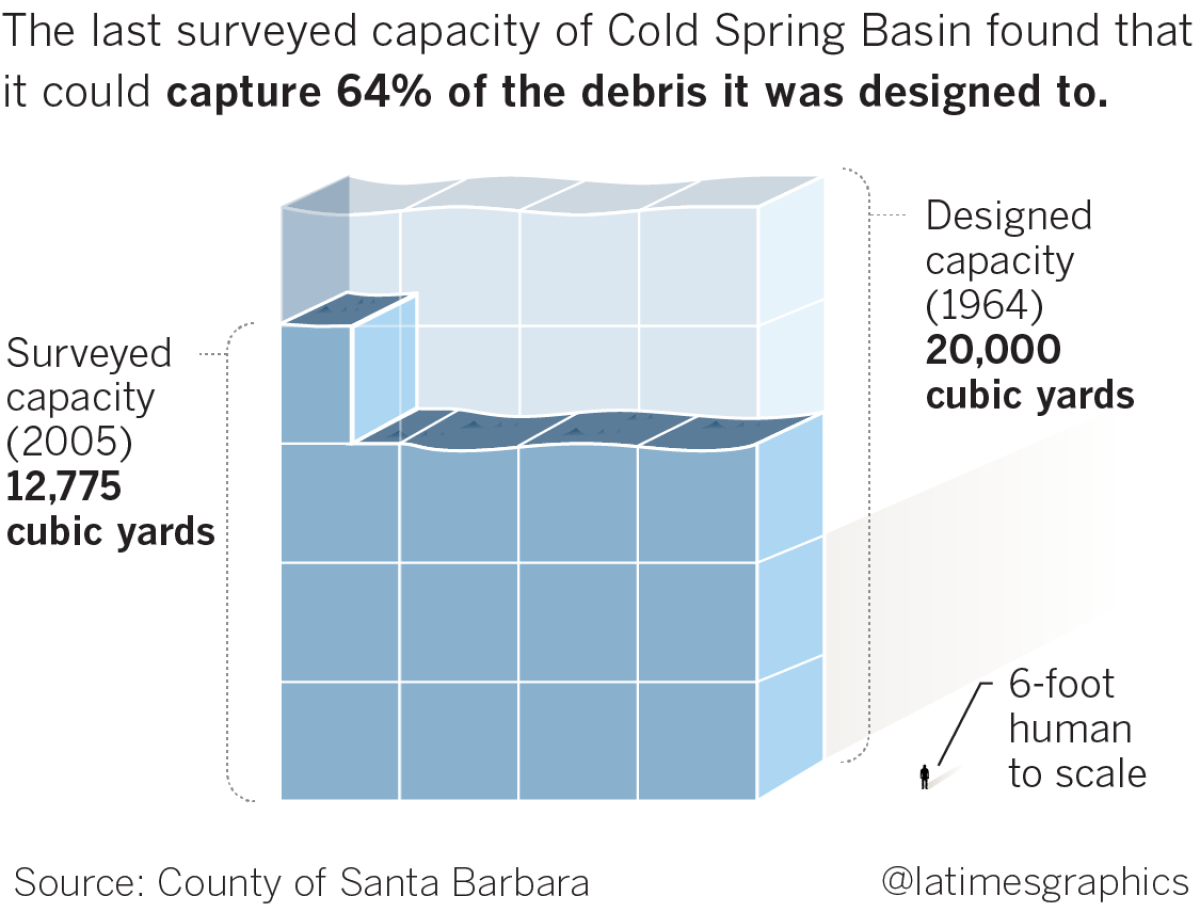

The catchment on Cold Springs Creek — about the size of a Little League baseball field — has a 16-foot high dam with a culvert at the bottom to let water and mud pass through. It was designed to stop 20,000 cubic yards of debris.

But even after it was cleared out in 2005, the basin still only had two-thirds of its capacity, a county survey indicated. During a major mudflow, that reduction would enable 7,000 cubic yards of storm debris that could have been trapped to flow into Montecito. (A cubic yard is about the size of a washing machine.)

It wasn’t only the Cold Springs Creek basin that had shrunk, according to records included in a 231-page county report on state of the flood control system, published online six months before the January disaster. Altogether, the 11 catchments surveyed had only 44% of their designed capacity.

But neither the flood control agency nor the community was worried. In documents released to The Times — in response to a public records request seeking all communications or records about the condition of the basins — no officials remarked that the catchments were more than half full with sand and rocks.

At the time, the mountains were stable, covered in thick chaparral.

Then last December, the fire came.

::

Montecito clings to a sliver of coastline against the Santa Ynez Mountains that abruptly rise 4,800 feet above the Pacific. The semirural small-town atmosphere, the ocean views and proximity to Los Angeles have made it a haven for Hollywood celebrities and the ultrawealthy — Oprah Winfrey, Ellen DeGeneres, Jeff Bridges, Natalie Portman and on and on.

But the instability of the slope has always made living there risky in the long term. The Army Corps began analyzing the debris threat in Santa Barbara and Montecito in 1964 as more people moved into the region.

That September, the Coyote Fire burned 65,000 acres above the towns, and with winter rains on the horizon, flood control engineers acted swiftly. Crews started building six basins — including the one for Cold Springs Creek. To avoid the state permitting required for larger dams, and with limited time and money, the Army Corps capped the barriers at 20 feet high.

The weather didn’t wait for them to finish. A storm rolled in on Nov. 9, 1964.

Jesse M. Williams, a foreman working on the Cold Springs Creek basin, had just given orders to a Caterpillar operator digging out the channel when he looked up the canyon.

“To my horror, I saw a mud and log flow about 3 feet high approaching down the channel at approximately 15 mph,” he recounted in a Corps report.

Williams ran up the side of the bank. The Cat operator spotted the mud surrounding his equipment, leaped out and ran with Williams. The mud rose over the top of the Caterpillar.

“We were running for our lives,” Williams said.

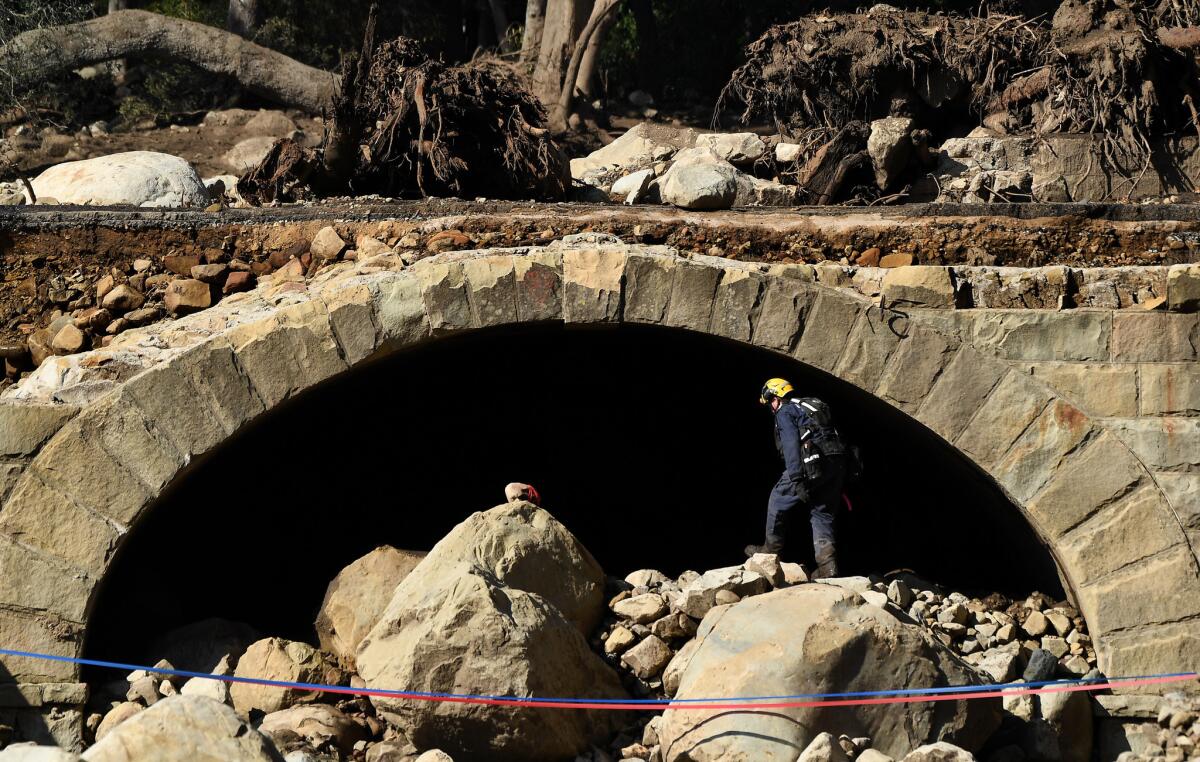

The mudflow roared down the creek, and its boulders and trees clogged the culvert under Hot Springs Road, diverting the debris down Olive Mill Road following the freeway overpass over U.S. 101.

The basins, built at a total cost of $860,000, were intended to be preliminary measures; the Army Corps was planning to construct a more comprehensive system.

The California Dept. of Water Resources, in summing up a confidential report from the Corps in 1965, noted the structures were designed for the level of flooding that could be expected every 10 years on average, but would be overwhelmed during severe storms.

“Considering the possibility of future fires in the area and the high rate of debris production in the watershed, the capacity of the debris basins should be increased …,” the state water agency concluded.

The agency implored county zoning and flood control officials to limit development in vulnerable areas and to put in place a strict regimen to keep the basins emptied. (While the Corps built the catchments, the county owns them and is responsible for their maintenance.) But building continued in the flood zones by the creeks, and the county did not allocate money to properly clean the basins.

In 1968 the Army Corps noted “a lack of adequate maintenance for the removal of the sediment buildup” at the Cold Springs Creek basin and two others.

El Niño flooding in January 1969 made it clear that the military engineers had vastly underestimated the amount of debris the mountains could produce. Boulders crashed through homes along Romero and San Ysidro creeks, and 70 residences were destroyed.

“Computed damages did not contemplate complete destruction of homes by debris,” wrote Pehrson of the Army Corps.

County Supervisor George Clyde and the manager of the flood control district at the time, Jim Stubchaer, lobbied Congress for more money to study the potential destruction from these creeks when a heavy storm follows a fire.

But a devastating oil spill off the Santa Barbara coast just weeks after the flooding changed the political climate, triggering opposition not just to more offshore drilling, but to any project viewed as threatening the natural environment. Plans for big debris basins or concrete storm channels suddenly faced strong push-back from the community.

In February 1971, an engineer with the U.S. Forest Service, Mike Rebar, surveyed Cold Springs Creek and its tributaries high in the Los Padres National Forest. Rebar proposed 30 to 50 low dams going all the way up the canyons — compared to one in the entire watershed today.

But seven months later, the Romero fire erupted east of Montecito and shifted priorities toward Carpinteria. The Corps focused on the immediate danger below the burn zone, building seven small basins.

With little community or political will to pressure the Army Corps to build more basins, the main creeks threatening Montecito receded into their oaken tranquility.

In recent interviews with The Times, Stubchaer, 88, said locals did not trust the Corps because the agency did not consult the public about its projects. He noted that the USDA Soil Conservation Service, working with residents and community leaders, managed to build a giant debris basin in 1977 with a 60-foot-high dam on Santa Monica Creek just east of Montecito, above Carpinteria.

Cleaning the county’s basins was difficult. With inadequate budgets, Stubchaer recalled, workers would simply shovel the sediment to the side, clearing a narrow channel so water could reach the dam’s culvert and continue down the creek.

At a county board of supervisors meeting in 1987, residents railed for 90 minutes against Stubchaer’s crews chain-sawing trees and plowing brush in the waterways, according to the Santa Barbara News Press. A Sierra Club member said it was time for him to stop his “nefarious activities.” The creeks, she said, “are not his private preserves to do as he pleases.”

When he left the agency in 1989, Stubchaer knew the channels and aging debris basins were not adequate for large floods.

Channels once proposed to be widened to 70 feet mostly span just 16 to 32 feet today, according to a private engineering report conducted for a citizens group this year.

The only catchment added in 47 years in Montecito was a very small basin built in 2002 on Montecito Creek, below where the worst damage had historically occurred.

Other regions with similar debris problems have been more proactive. After mudslides killed more than 41 people and demolished 146 homes in the Montrose area in 1934, Los Angeles County urged the Army Corps to build basins to protect the foothill communities of the San Gabriel Mountains. Today, there are 119 debris basins countywide, with 17 of them bigger than 100,000 cubic yards.

Of the 17 basins in Santa Barbara County, only one is that large — the one above Carpinteria.

By 2016, the fear of serious flooding in Montecito was so low that Santa Barbara County agreed to remove five of the basins, including Cold Springs, to comply with a federal requirement to provide habitat and passage for southern steelhead trout. The dams blocked the fish’s passage to potential spawning areas.

In June 2017, the county released its plan to take down those five catchments by 2026.

Six months later, the massive 281,000-acre Thomas fire roared through every watershed above Montecito and Carpinteria, burning deep into the rainy season in late December. The threat of catastrophic erosion loomed as county crews cleared out the debris basin at Cold Springs Creek and four others.

Many of the catchments were packed with river cobble and coarse sand, leaving less room to hold back the debris — despite county policy that they be emptied whenever they became 25% full.

Tom Fayram, the deputy director of public works, alerted state emergency officials and the Army Corps that the county needed help cleaning out basins and creek channels before the first storm of the rainy season. He feared that Montecito and Carpinteria could be in the direct path of a major mudslide.

“As it is Dec. 10, we have precious little time,” he wrote to Col. Kirk E. Gibbs, the commander of the district. “We all need to work extremely fast. The watersheds burned were almost totally burned so our assumption is worst case.”

Starting on Dec. 21, crews worked for two days and took a three-day break over Christmas. They worked for three days, took a four-day break over New Years and resumed for three more days, wrapping up by Jan. 5. Dump trucks took more nearly 1,200 loads to an out-of-commission landfill on Foothill Road. Fayram reported that the catchments were “cleaned out.”

But the work was only done in five of 11 basins below the burned section of the mountain front. And county officials said they didn’t have the original Army Corps designs to guide them. At Cold Springs Creek, a big portion of the basin was not dug out — a third of the dam’s length was buried under sediment and vegetation. On top of that span, an 18-year-old oak grows. Historic aerial photos showed the county last emptied that area in 1969.

After the excavation, a county surveyor, Scott Brichan, set out to calculate the capacities of the basins. Brichan’s findings, which were not released to the public at the time, might have unsettled residents.

Of Montecito’s three main basins, he reported to the flood control district, Romero Canyon’s had a capacity of 7,821 cubic yards, compared to a design capacity of 27,000. There was no explanation why the number was so low.

San Ysidro’s basin had a volume of 6,112 cubic yards, compared to its design of 11,000, he wrote. If correct, this meant that even after digging out an estimated 3,000 cubic yards of material, the basin remained 44% full.

The January storm came before Brichan surveyed Cold Springs Creek.

Fayram, the deputy public works director, said that the surveys were wrong or misleading, insisting the Montecito basins were emptied to their full original capacity. On Romero Canyon’s reported capacity, he said there was “no way” it was more than two-thirds full before the storm.

“Sorry, it’s flat out wrong.”

He did not respond to questions about why the numbers would have been off, and why they have not been corrected. The surveyor, Brichan, declined to comment.

“I guess I never considered that anyone could, or would ever, question the completeness of our work,” Fayram wrote to The Times in March.

After several exchanges, the county’s attorneys advised Fayram and other flood control officials not to speak with The Times. Questions were referred to a county spokeswoman, Gina DePinto. She didn’t address the surveyor’s numbers but said: “It’s very simple, and we have said many times, they cleaned out what was actually present.”

In one internal email before the clean-outs, Fayram assured a county supervisor he would “minimize the amounts” of sediment brought to the landfill on Foothill Road, which was in her district. It was the only place trucks took the excavated material.

With a Pineapple Express storm forecast for the night of Jan. 8, county officials issued mandatory evacuations — but only in the neighborhoods closest to the mountains, north of East Valley Road, even though many communities outside that area were in greater danger. FEMA had long ago mapped flood zones along the creeks all the way to the ocean.

Residents had no idea of the devastation that the Santa Ynez Mountains could let loose in a major storm after a fire. They expected water or mud damage at worst, especially those living far from the rugged canyons. They put sandbags across their driveways and plywood across their front doors.

Few considered how the giant sandstone monoliths adorning yards and parks arrived there; or that the gentle slope they lived on was the product of violent rock-and-mud flows that had taken place periodically over thousands of years.

The creeks they knew were mostly tame, even in the wet season, gurgling along, feeding the aquifer and the wildlife and the gnarl-armed oaks that gave the area its natural allure.

The Johnson family loved the wildlife — the hawks, rabbits and bobcats — in the mostly dry streambed behind their home. They lived two miles below the Cold Springs Creek basin on a relatively flat stretch of Olive Mill Road, twice as close to the ocean than to the canyons. They never saw mountain boulders as a threat.

The Johnsons were in a voluntary evacuation zone, and with the rain coming, Berkeley “Augie” Johnson recalled that he was mainly worried the creek might get high and water might seep into the house. So he stacked two rows of sand bags in front of his doors before sitting down to dinner. He watched Alabama beat Georgia in the college football championship and went to bed.

The storm rolled in after midnight and at 3:30 dropped 0.66 inches of rain in just 15 minutes. The downpour was more intense than anyone predicted, breaking records.

Fast-moving mud and ash picked up the sandstone boulders and burned trees and surged down the mountain. Within half an hour, the basins were overflowing. Mud gushed over the dams on Cold Springs and San Ysidro creeks with such velocity that it fractured both dams in places and coated nearby trees 30 feet high.

Below its basin, Cold Springs Creek joins another stream to form Montecito Creek, which runs through the center of town. The debris quickly clogged up bridge culverts, then spilled into the same neighborhoods flooded in 1964 and 1969.

Johnson woke up to the heavy rain and walked outside to check new gutters on his roof. He looked a few hundred yards up the creek and saw foliage rustling hard — in little wind. Trees started falling as if they were being slapped down. A low rumbling vibration grew louder.

He squinted to see better. Blurry movement in the distance sharpened into a mass of boulders, logs and metal rolling toward him, more like an avalanche than a flood.

As he ran inside, his back wall imploded, mud raced in and rose to his waist. He rushed upstairs where his wife, 13-year-old daughter and 20-year-old son had gone to sleep just in case the downstairs bedrooms got flooded.

The house groaned from the force of debris pushing against it, wood beams cracked, windows exploded. Boulders had ripped away the master bedroom without a trace, and he feared the second floor above it would cave in. The family crawled onto the roof.

Johnson stood by his chimney in disbelief. A 30-foot cylindrical tank floated by spewing gas, and boulders thudded against the house, tearing it away piece by piece.

“It’s a good thing we put up those sand bags, Dad,” his son deadpanned.

Throughout Montecito, the deluge obliterated concrete landscape walls and wiped away cars and houses, sweeping up more wreckage as it rushed to the ocean, two to three miles from the mountains. People living on high ground blocks from the destruction woke up thinking there was an earthquake.

As it had in 1964 and 1969, debris followed Olive Mill Road down to U.S. 101, crossed an overpass, spilling over the sides, and emptied into the Pacific.

By daybreak, Montecito Creek had taken 17 lives. Four more were killed by San Ysidro Creek debris flows. Two others died on Romero and Hot Springs creeks. Bodies were found more than a mile from their homes.

Seventeen of the 23 deaths happened outside of the mandatory evacuation zone.

The Johnsons survived, but their house was destroyed.

At sunrise, residents far from the disaster zone saw strange rain ruts running straight down the mountains — a rare glimpse of the immense hydrogeological forces that created the foothills and coastal plain they lived on.

No one, not even county officials, could fathom the destruction.

The consequences of decades of inaction were starkly drawn: In Carpinteria, no one died, and no homes were lost, because of the giant basin the USDA built 41 years ago on Santa Monica Creek.

“It really saved Carp from untold misery, probably not that different from what Montecito had,” Fayram told a local online news site, Coastal View.

::

With the mountainsides still bare, Montecito remains in danger. The U.S. Forest Service predicted that the Cold Springs and San Ysidro watersheds would see three to four times their normal peak flows during heavy storms until 2028.

Significant parts of the dam and basin at Cold Springs Creek are still buried.

A view of Cold Springs Creek Basin from before and after the Montecito mudslides. (Google maps)

Patrick McElroy, a Santa Barbara city fire chief who retired in March, started a nonprofit with wealthy investors to study the ongoing risk and team up with the county and three engineering firms to prevent another catastrophe.

The Partnership for Resilient Communities has been calling for emergency measures, including a debris monitoring system and 14 removable steel-hoop retention fences at points along the creeks in Montecito. The group is privately raising $5 million to buy and install the nets and scrambling to get the necessary permits. Once the vegetation grows back, McElroy said, the fences would be removed.

He was hoping to have them installed before the rains hit, but is still trying to get them permitted by the county.

A Colorado engineering firm hired to review his group’s plans and convince regulatory agencies of the danger noted that the rain that occurred Jan. 9 was rare, but not unprecedented. Storms with twice the intensity hit the county in 1998 and 2015 when the mountains were not bare.

McElroy added that federal climatologists are predicting January 2019 will have a 70% chance of El Niño conditions, which normally bring above-average rains.

“Urgent action is needed to protect life and property in Montecito from the impacts of future debris flows,” the Colorado engineers wrote in June.

That month, county officials filed papers to request FEMA funding to fortify and expand the basins at Cold Springs, San Ysidro and Romero creeks in the next two years. The county would also acquire property to build one additional basin each on San Ysidro and Montecito creeks by 2022.

The hard-hit areas are still disaster zones, with mud lines marking walls and eaves of ruined houses. A small number of residents are starting to rebuild, often in the same spot. Some, not all, are raising the building pads of their new houses.

Alison Hardey, 56, a Montecito cafe owner who has lived there and in neighboring Carpinteria her whole life, wonders if people are once again falling into a state of willful amnesia.

She often hikes in the canyons above the debris basins. She loved climbing these great sandstone rocks as a girl. Now they give her a chill — they look like they’re just “waiting to come down.”

“You feel how enormous this thing was,” she said.

“We’re like ants against these mountains. We probably should have never been here to begin with.”

Produced by Swetha Kannan.

Graphics: Lorena Iñiguez Elebee, Swetha Kannan.