This LAX-adjacent ghost town is now ‘priceless coastal real estate’ for rare owls

When the Los Angeles beachfront community of Surfridge disappeared decades ago to make way for the jet age, nature was slow to reclaim the sandy dunes and upscale lots that once dominated the path of planes taking off from Los Angeles International Airport.

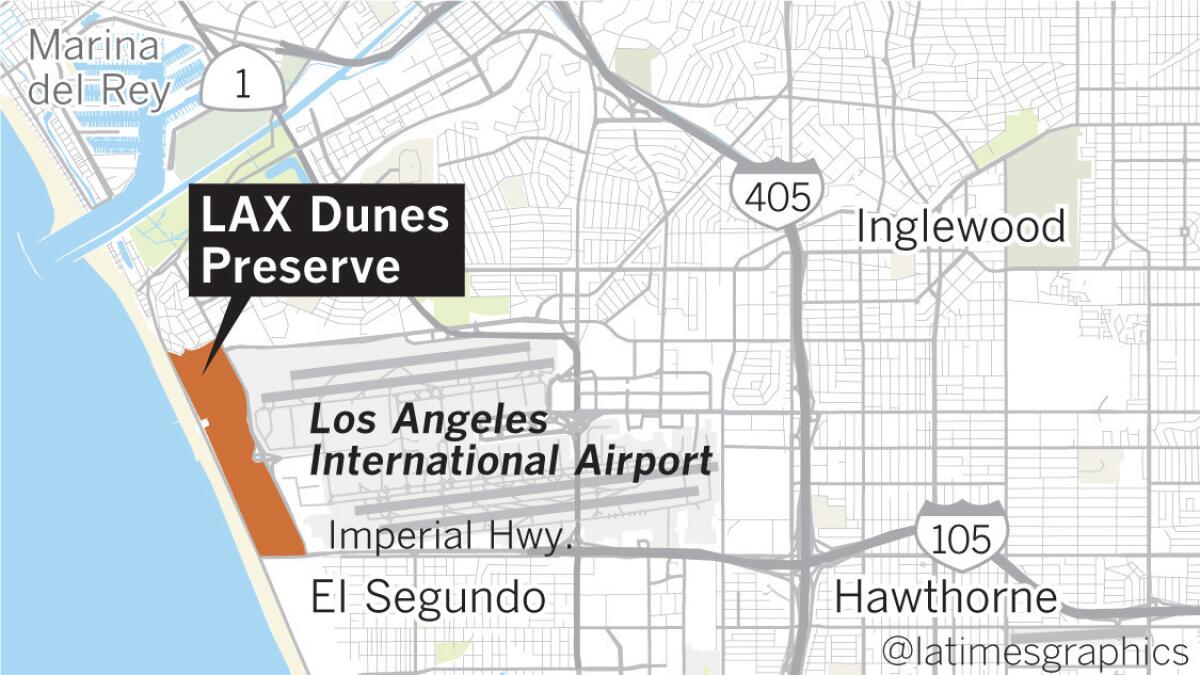

Today however, this 2-mile ghost town of vanished homes supports a growing list of protected and endangered species that have somehow adapted to the throttled-up roar of passenger jets. Surrounded by hurricane fencing and “no trespassing” signs, the LAX Dunes Preserve is now a haven for some of the rarest creatures in California.

Scientists were elated by the recent discovery of 10 burrowing owls hunkered down in the 302-acre preserve — the most seen here in four decades. Among the raptors are a breeding pair that stand guard over a nest and hiss at occasional passersby.

“This is very exciting — a real stunner,” said Pete Bloom, a biologist and avian expert who was helping to conduct a wildlife survey this month.

“For wintering owls, this tiny chunk of land has become priceless coastal real estate,” he said, raising his voice over the deafening roar of aircraft a few hundred feet overhead. “That’s because there is no place else left for them to go in the city of Los Angeles.”

The owls are the latest species to add complexity to an undulating habitat of sand, native brush and invasive weeds — a small wild island surrounded by asphalt, subdivisions and freeways.

The reappearance of owls after a long absence signals the success of a restoration program that began in the 1990s and is now recognized as one of the most successful in Southern California.

It is also a sign of nature’s resilience, experts say.

“For biologists, the preserve has become an ecological hot spot sandwiched between a popular beach and the third-busiest airport in the nation,” said Robert Fisher, a U.S. Geological Survey biologist. “We aim to make sure things stay that way.”

The range of biodiversity in the windswept landscape — which is off-limits to the public — underscores the difficulty that government wildlife biologists face ensuring the survival of rare species in an urban setting.

Biologists believe there is a chance that juvenile burrowing owls might become permanent residents of the preserve, which is just one small fragment of a dune system that once stretched along the Pacific Coast from Point Conception, west of Santa Barbara, to Mexico.

It is already home to 900 species of plants and animals, including federally endangered El Segundo blue butterflies, whose numbers were in steep decline due to habitat loss. Today, thousands of blues flutter over robust stands of buckwheat during certain times of the year.

Other species on the rebound in the isolated dunes include native evening primrose and California gnatcatcher. A recent survey of the federally protected bird found three pairs and six juveniles.

A colony of Blainville’s horned lizards has expanded its range throughout the preserve, along with the harvester ants that sustain them.

Ongoing genetic tests aim to determine whether the prehistoric-looking creatures belong to a subspecies unique to the dunes, Fisher said. Up until a few years ago, the 4½-inch lizards resided only on the preserve’s southern boundaries.

Then there are the legless lizards, which were recently discovered in the windswept dunes.

The legless lizard remains one of the most poorly studied reptiles in California, so researchers were thrilled to find six elusive specimens this month. A team led by Fisher and USGS ecologist Adam Backlin found them after turning over a few boards that were placed there earlier to create the kind of moist, cool area the reptiles prefer.

Fisher reached down and scooped up one of the lizards for a closer look. They measure about 8 inches long and are as thin as a drinking straw. “How cool is that?” he asked out loud as the creature wriggled in the palm of his hand.

Federal scientists are discussing proposals to reintroduce animals that roamed the dunes a century ago but are no longer there. One candidate could be the Pacific pocket mouse, a critically endangered, thumb-sized mammal previously found only on a gun range at Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, about 115 miles south.

In the meantime, volunteers organized by nonprofit organizations such as the Bay Foundation and Friends of the LAX Dunes have been working with authorities and the preserve’s owner — Los Angeles World Airports — to help restore the landscape.

Each month, they uproot the invasive weeds that sprout along the cracked, forgotten roads of Surfridge. Developed in the 1920s and ’30s, Surfridge was an isolated playground far from downtown — at least up until the time it was purchased by LAX and cleared of homes that sat just beyond the western edge of the airport’s runways.

Today, after three years of weed removal, “we’re seeing a surge in native vegetation in some of the places we’ve cleaned up,” said Melodie Grubbs, director of watershed programs for the Bay Foundation. “Invasive plants including mustard and Russian thistle, for example, are being replaced by lupine, deer weed, evening primrose, buckwheat and California poppies.”

Weeds weren’t the only invading species, however. There was a time when voracious feral cats prowled the dunes. But strategically placed wildlife cameras suggest that is no longer the case.

Against cats, burrowing owls don’t stand a chance.

The nearest other burrowing owl is a lone bird about 27 miles away at the Naval Weapons Station Seal Beach in Orange County, biologist and avian expert Bloom said.

Though burrowing owls were once among the state’s most common birds, their numbers have been dropping steadily since the 1940s due to urban development, eradication of the rodents they feed on, pesticides, predation by domestic animals, vehicle strikes, collisions with wind turbines and shootings.

“With almost no place left for migratory burrowing owls to rest and bulk up in the winter months,” Bloom said, “the dunes have become critical to the survival of the species.”