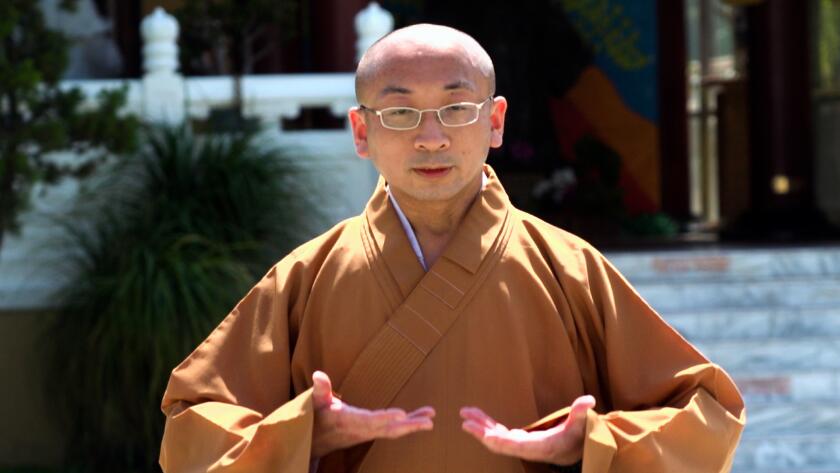

When we think of meditation, we often picture someone sitting as still as a statue, said Venerable Hui Cheng, a monk at Fo Guang Shan Hsi Lai Temple.

But that’s just one form of meditation. For the monastics at Hsi Lai Temple, meditation isn’t a singular activity.

“It is a way of life — and an attitude of life that we carry in everyday existence,” he said. “Everything we do in our lives, as long as we are able to apply the mind correctly, with focus and attention, can be meditation.”

Since the pandemic started, Venerable Hui Cheng has seen more people turning to faith leaders for mental health guidance.

For the record:

9:32 a.m. June 2, 2023A previous version of the story stated that Hsi Lai Temple opened in 1989. It opened in 1988.

Hsi Lai Temple is a monastery in the hills of Hacienda Heights. The architecture, statues and gardens resemble the buildings and grounds of Chinese monasteries of the Ming and Qing dynasties. The Fo Guang Shan Buddhist Order, which was founded by the late Venerable Master Hsing Yun, has more than 300 temples worldwide. The headquarters is in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, and the Hacienda Heights temple, which opened in 1988, was the first branch built outside of Taiwan. “Hsi Lai (西來)” means “coming to the West.”

The temple promotes Humanistic Buddhism, a philosophy that uses Buddhist teachings to assist in day-to-day activities and relationships.

Venerable Hui Dong, the Abbot at Hsi Lai Temple, explained that the teachings of Humanistic Buddhism can benefit people of any religion and background. It’s a practice that helps people find clarity of mind.

Fo Guang Shan advocates the three acts of goodness: Do good deeds, say good words, and have good thoughts.

Meditation is one way to fulfill these acts and purify the mind. “We are inspired to not hold onto things that are inherently fluid and transient in nature,” said Venerable Hui Cheng, who works with the temple’s department of social education and outreach. “And that is where sustainable happiness is allowed to grow and develop.”

The Times visited Hsi Lai Temple to learn about the different types of meditation that are done at the mountain monastery. Here are some tips shared by the temple’s monks.

Sitting meditation

The Hsi Lai Temple’s traditional sitting meditation sessions take place in its meditation hall, with a Buddha at the center.

After taking off your shoes, you are encouraged to sit in the quarter lotus position — legs crossed with one ankle on top of the other shin — if you are a beginner. Sit up straight and put your hands in front of you in a meditation mudra: palms up, left hand on the bottom, right hand on the top with the two thumbs touching.

“We tuck in our chin and have the tips of our tongue against the palate, our eyes closed, and then we relax the body as we slowly bring our focus to the point between the nose and top lip,” Venerable Hui Cheng said. “As we bring the focus to the top lip, we allow the mind to be aware of the sensations of breathing in and out naturally.”

They typically meditate for 30 minutes.

Venerable Hui Cheng recites the goal of mindfulness while meditating: “What has happened in the past is history. Nothing for us to bother ourselves over. What has yet to come is the future. Something that does not require speculation. The most important thing at this particular point is now — just to become aware of the present moment.”

It’s natural for what he calls “our monkey minds” to wander around as we try to focus. For some, the barrage of unwanted thoughts and emotions may feel like a “rude awakening,” he said. But he reminds us to observe our thoughts and feelings without judgment — and slowly, gently focus our minds back on our breathing.

“The moment we give our mind a task to do, we’re training it,” he said. “We are refining the art of attention, and once we are focused on the present moment, we are afforded the opportunity to be inspired by our wisdom to act prudently and with wholesomeness.”

The Venerable Hui Dong brings it back to the teachings of Humanistic Buddhism. “Whenever the mind gives rise to greed, cravings, anger and hate, [you can] train the mind to say good words, have good thoughts and try to calm itself,” he said. “Sometimes it just requires people to practice patience — being patient [with] all these upsurges of emotion.”

Walking meditation

“Many times when we walk in our daily lives, our minds are elsewhere,” Venerable Hui Cheng said.

When doing walking meditation, the focus is on relaxing the body, centering yourself and uniting the mind and body.

There are two types of walking meditation: slow, where the focus is on the feet and very slowly transferring the weight from heel to toe as we walk; and brisk, which involves swinging the arms high while taking big strides.

“The focus should be on the entire body and just becoming at ease with the movements,” he said. “The reason we swing the arms nice and high is so that we’re activating the lymph glands. It releases tension and a lot of poisons inside the body.”

When the monks do walking meditations, they adjust the speed based on how their bodies feel in the moment, Venerable Hui Cheng said.

“If the body is tired, if it is full of torpor, then we do our walking very quickly, and that allows the mind to freshen up,” he said. “When the mind is busy, we do it slower, so the mind can anchor itself on a point of meditation.”

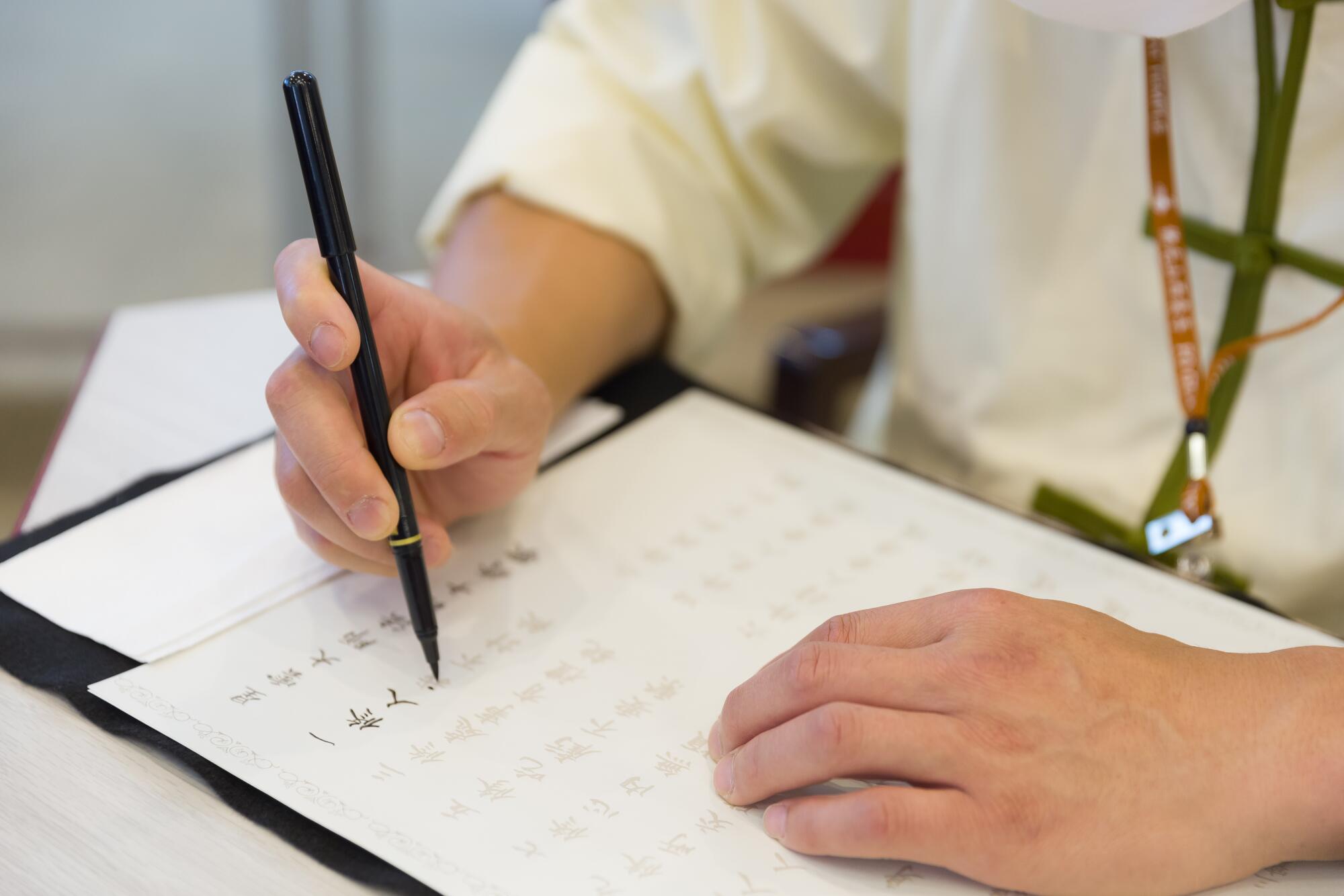

Sutra calligraphy

Activities such as calligraphy that put you in a zone for a long period of time can act as a good transition into a quieter state of mind, Venerable Hui Cheng said.

Every year on May 16, to commemorate the founding of the Fo Guang Shan Buddhist Order, the temples hold an event where members, family and friends around the world simultaneously transcribe the Heart Sutra together.

“It is a way to connect with wisdom,” he said. “The Heart Sutra is all about living a life that is free of the commitments that create suffering.”

It takes about an hour to write the entire thing, he said.

To do Chinese calligraphy, think of the brush as a dancer as you write, he said.

“The purpose of sutra calligraphy is to allow the mind to have a meditation object,” he said. “And in this case, it’s going to be the tip of the brush. As we put the brush down to paper, we focus on the tip, as it very naturally goes through the motion of transcribing.”

Eating meditation

Eating can also be meditation. The temple’s dining hall hosts a vegetarian buffet — serving fresh dishes without onion and garlic. But eating meditation is less about the type of food being eaten than about the time spent focusing on the food and appreciating each element of the meal.

In our daily lives, we often are multitasking when we eat. But “there’s a saying in Buddhism that when we walk, we only walk,” said Venerable Hui Cheng. “ When we stand, we only stand. When we sit down, we only sit down. And when we recline, we only recline — and do nothing else.”

Visitors to the Hsi Lai Temple dining hall are encouraged to participate in five meal contemplations:

- Assess the amount of work involved; weigh the origins of the food.

- Reflect on one’s own moral conduct; perfect or not, take this offering.

- Safeguard the mind against all error; do not give rise to hatred or greed.

- Regard this food as good medicine; so as to treat the weakened body.

- In order to accomplish the Way; one deserves to accept this food.

Yi Jin Jing

Yi Jin Jing is a series of 12 exercises coordinated with breathing. In Chinese, “yi” (易) means change, “jin” (筋) means tendons, and “jing” (經) means methods.

Venerable Hui Shiuan, who also works in the temple’s department of social education, has been practicing Yi Jin Jing for 17 years.

Yi Jin Jing is often done before a sitting meditation, he said. The movements help with blood circulation and the body’s meridians — which in Chinese medicine refer to the pathways that energy, or qi, flows through.

Venerable Hui Shiuan likes teaching Yi Jin Jing because the movements are relatively gentle and simple. Many people can learn the movements in only 20 minutes, he said. And you can circle through the 12 movements in about six or seven minutes. For a longer workout, you repeat the movements, counting each recurrence by the breath.

When Venerable Hui Shiuan taught Yi Jin Jing in Malaysia, he had students of all generations. In the U.S., his classes draw an older crowd. “When you get older, if you need help lifting up your feet to walk up stairs or lifting your arms up, doing Yi Jin Jing can help achieve those results relatively quickly,” he said in Chinese.

He encourages beginners to be patient. When learning, at first you might feel tired, he said. But after a couple of weeks, doing Yi Jin Jing should make you feel good.

“If you practice it in the morning, you’ll feel like you have more energy,” he said. “If you do it at night before you go to bed, you’ll be sure to sleep soundly.”

Meditation in action

Altruism is one of the core concepts of Humanistic Buddhism. The Hsi Lai Temple hosts regular Day of Giving events, where volunteers can come “support the temple, form affinities and cultivate merits.” They help do chores, including gardening and wiping down the Buddha statues.

“In Buddhism, we say that everything we do has a purpose, and everything is practice,” Venerable Hui Cheng said.

So if you’re cleaning the environment around you, use it as an opportunity to cleanse your mind, he said.

“Most people have a tendency to be overly preoccupied with one’s self, one’s likes and dislikes and what one endeavors in life,” Venerable Hui Cheng said.

Getting rid of the ego and serving the community is what helps us find joy, he said.

Last takeaways

Venerable Hui Dong encourages those interested in Humanistic Buddhism to learn more about its teachings and gain greater understanding of how our minds work. A place to start is with one of the many books by Venerable Master Hsing Yun, the monastic order’s founder, including “For All Living Beings: A Guide to Buddhist Practice” and “Being Good: Buddhist Ethics for Everyday Life.”

The temple also offers classes, both in person and online, as well as Dharma services.

Some people may do meditation as a way to relax, but the goal is to “really release themselves from the anger or the attachment to the materials or to other things in their life, which eventually would cause the stress and the pain,” he said.

It’s about finding peace amid the hustle and bustle of daily life, Venerable Hui Cheng said.

“As soon as we allow the mind to focus on the body, to able to slowly bring it back and anchor it on a particular point — no matter how chaotic the world outside can be, our minds are very still.”

About The Times Utility Journalism Team

This article is from The Times’ Utility Journalism Team. Our mission is to be essential to the lives of Southern Californians by publishing information that solves problems, answers questions and helps with decision making. We serve audiences in and around Los Angeles — including current Times subscribers and diverse communities that haven’t historically had their needs met by our coverage.

How can we be useful to you and your community? Email utility (at) latimes.com or one of our journalists: Jon Healey, Ada Tseng, Jessica Roy and Karen Garcia.