- Share via

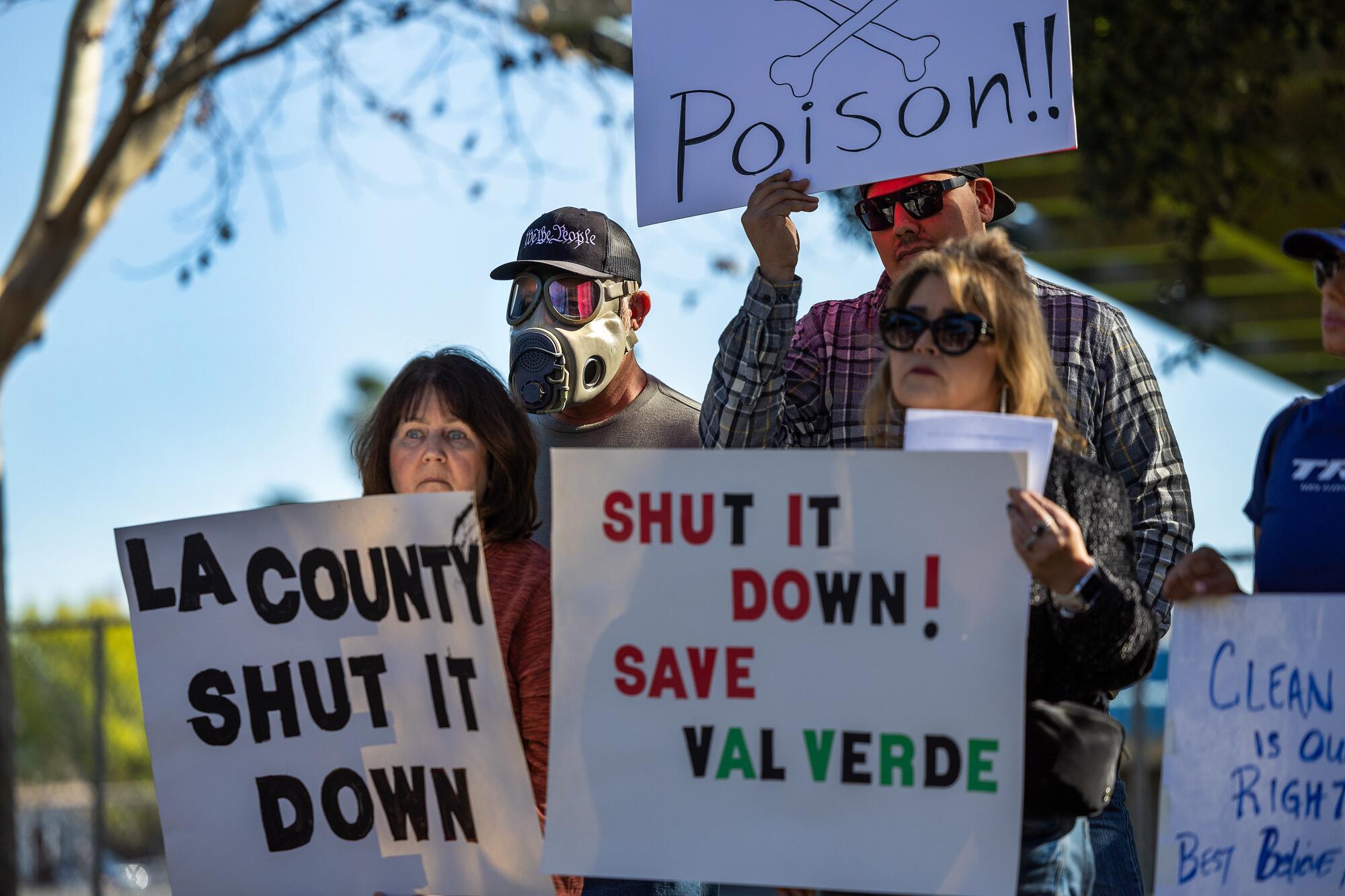

Federal regulators say it’s an imminent danger, a Los Angeles County supervisor says she has “lost faith” in its management and aggrieved neighbors have filed two lawsuits demanding an end to its operations. Some residents recently complained that its odors are so pungent they have been made to gag or vomit.

As owners of the troubled Chiquita Canyon Landfill struggle to contain noxious fumes and contaminated runoff caused by an underground garbage fire, residents and public officials increasingly are calling for the Castaic facility’s closure.

Yet even as efforts to shut down the facility gather strength, some officials and environmental advocates are skeptical such a move will help. They say that not only would closing the landfill fail to solve the crisis, it would strain the region’s system of waste collection, raise fees and increase truck traffic and pollution.

“It’s not going to do anything to help with the existing problem,” said Jane Williams, executive director of California Communities Against Toxics. “If you decide you want to close the landfill because it’s a god-awful mess, then you should do that. But that’s not going to help the potential endangerment problem.”

The U.S. EPA orders Chiquita Canyon landfill to take immediate action to safeguard the public. Meanwhile, nearby residents have filed suit to close the facility.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, a heat-producing chemical reaction likely started deep within a closed portion of the landfill in May 2022. Since then, increasing heat and pressure have created volcano-like conditions, triggering eruptions of benzene-contaminated water and the release of noxious gases. The agency, which is overseeing efforts to control the reaction, has called the situation an “imminent and substantial endangerment” to nearby communities.

Because the smoldering conditions are occurring in an area of the dump that has been closed for decades, shutting down the active portion of the landfill would not stop it, according to officials. Equally concerning, some say, is that it remains unclear whether similar chemical reactions could occur in the county’s other aging landfills, as officials have yet to determine an exact cause.

Los Angeles County Supervisor Kathryn Barger, who was initially resistant to closing the facility, said recently that she had lost confidence in the landfill’s leadership. She is now calling on state officials to step in and decide whether the landfill should be closed for public health reasons. Barger argues that if the county closes the landfill on its own, the decision would face legal challenges.

“While the prospect of closing the facility presents formidable challenges, if deemed warranted by state experts I am hopeful that they will exercise their authority to do so,” Barger said at a recent meeting.

Among those officials calling for the landfill to be closed is Assemblymember Chris Holden (D-Pasadena). U.S. Rep. Mike Garcia (R-Santa Clarita) has also called for the landfill’s operations to be paused until there is a clear path toward abating the health effects.

Chiquita Canyon accepts about 2 million tons of garbage annually — roughly 34% of all municipal solid waste disposed of in the county. Its closure would likely require policymakers to institute drastic reforms on how the nation’s most populous county handles waste. Those changes would come at a time when California is already struggling to implement recycling and composting programs.

Among those who are arguing to keep the landfill open are officials with Waste Connections , the landfill’s operator.

“Calls to close the landfill are misguided as it would have no effect on the ongoing (reaction),” read a company statement. “The Chiquita Canyon Landfill is the second largest landfill in the County and it plays a vital role in the County’s ability to safely and quickly gather, process, and dispose of thousands of tons of waste, six days a week.”

Miki Esposito, assistant director of L.A. County Public Works, said other county landfills have the capacity to accept more waste in the event of Chiquita Canyon’s closure. However, garbage haulers would likely need to drive longer distances, burning more fuel and releasing more pollution.

There’s also the risk that shuting one of L.A. County’s six major landfills could exacerbate tensions in communities surrounding the other landfills.

The possibility that trash bound for Chiquita Canyon could end up in Sunshine Canyon Landfill — some 12 miles away in Sylmar — has residents there worried.

The North Valley Coalition of Concerned Citizens has been complaining about odor issues at Sunshine Canyon — the county’s largest landfill — for years. The problem has grown even more pronounced due to heavy rainfall overwhelming its pollution control systems. The landfill typically receives more than 7,000 tons daily, but its permit allows it to accept up to 12,100 tons.

Wayde Hunter, president of the community group, said he empathized with Chiquita Canyon residents, but “as much as I want to see their problem fixed, we hope it would never mean we would somehow have to absorb the trash that they weren’t taking.”

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

Residents surrounding Chiquita Canyon and Sunshine Canyon have both pleaded for the county to explore a long-sidelined plan to use trains to haul garbage to a remote desert landfill about 100 miles east of San Diego.

Experts point out that closing a landfill and redirecting waste elsewhere will likely result in higher garbage collection fees.

Mike Mohajer, a retired engineer with the L.A. County Department of Public Works, said he supports the landfill’s closure as a matter of public health. However, he wonders if the prospect of increased fees is causing officials to delay action.

“Nobody wants to address it, because they are all worrying that if Chiquita closes, the landfill tipping fees are going to be raised. And with the coming election is not going to be the time that you want to increase fees,” Mohajer said.

A county-hired environmental firm found that toxic gases released by Chiquita Canyon Landfill do not pose a significant cancer risk. Residents are skeptical.

Environmental advocates say the crisis at Chiquita Canyon has exposed the need for major changes in how county residents and officials approach solid waste. They say policymakers should be working harder to increase recycling, as well as converting organic waste, such as food scraps and tree trimmings, into compost for farming and gardening.

In addition to alleviating landfill capacity issues, advocates say composting would reduce lung-irritating hydrogen sulfide and planet-warming methane, which are both produced by organic waste decomposing in landfills.

But the state has fallen far short of its waste reduction goals.

In 2016, the Legislature passed a law requiring Californians to divert 50% of all organic waste from landfills by 2020, and 75% by 2025. However, the state has cut its annual tonnage of organic waste from 21 million to 19 million since the law was passed — only a 10% reduction, according to CalRecycle, the state agency overseeing waste disposal and recycling.

The law also required homes and businesses in almost every community to have green bins for organic waste by 2022. But some communities still haven’t deployed the new containers. The rollout, experts say, has been plagued by a lack of funding and interruptions from the Covid-19 pandemic.

Amid the discussion of a landfill closure and composting, however, lies a deeper and more troubling question of whether similar chemical reactions could erupt in any of the roughly 100 active or inactive landfills across the Greater Los Angeles Area. Such reactions can take years to dissipate, according to CalRecycle.

“Is Chiquita Canyon the first of many?” Barger asked recently. “We don’t know because this is not a part of the landfill that’s currently intaking any of the garbage. It’s actually in an area that’s been dormant for about 30 years.”

The chemical reaction brewing inside Chiquita Canyon appears to be “caused by oxygen intrusion,” according to an EPA report that cites interviews with landfill staff. This is consistent with a CalRecycle assessment that found the landfill’s gas collection wells had experienced elevated levels of oxygen.

Similar to oil drill sites, landfills have an extensive network of underground wells to extract gases produced when waste decomposes. But if the landfill overdraws these gases, these wells can introduce oxygen, which can speed up waste decomposition and produce heat.

The South Coast Air Quality Management District has previously approved several requests by the landfill to operate with oxygen and temperature levels higher than its permit allowed. This included the gas well CalRecycle identified as the “point of origin.”

The air district said these levels remain consistent with federal standards but emphasized that the EPA has not officially determined the cause of the reaction.

“The current situation at Chiquita Canyon is unprecedented and is unlike anything South Coast AQMD has observed at any landfills — active or inactive,” said Nahal Mogharab, a district spokesperson.

Amid thousands of complaints, Waste Connections has vowed to provide funding for residents to relocate temporarily, or to make home improvements that would mitigate odors.

However the company disputes government assertions that an incursion of oxygen triggered the reaction. They also deny that the chemical reaction is an “underground fire,” and describe it instead as an “elevated temperature” event.

Officials say temperatures have risen above 200 degrees in the affected area and have forced liquid waste to erupt in geysers or to leak from fissures in the face of the landfill.

Water sampling has shown an increasing amount of cancer-causing benzene in this liquid waste, which experts say is generally an indication of rising temperatures. Some of this contaminated water contains enough chemicals to be considered hazardous waste and potentially ignitable.

Chiquita Canyon, which had been sending the polluted water to two Southern California facilities, is now transporting some of this hazardous liquid waste to Utah.

The landfill is also stockpiling about 2 million gallons of this liquid waste in scores of metal storage containers on site. Its workers have been adding hydrogen peroxide and iron to the liquid waste to reduce the benzene concentrations.

One worker was injured when a hose used to apply hydrogen peroxide burst.

For some, the incident was yet another indication that the landfill’s staff is not fit to handle the situation.

“The landfill is the problem,” said Mohajer, the retired public works engineer.