Arts Preview: Meet Ivo van Hove, the most provocatively illuminating theater director right now

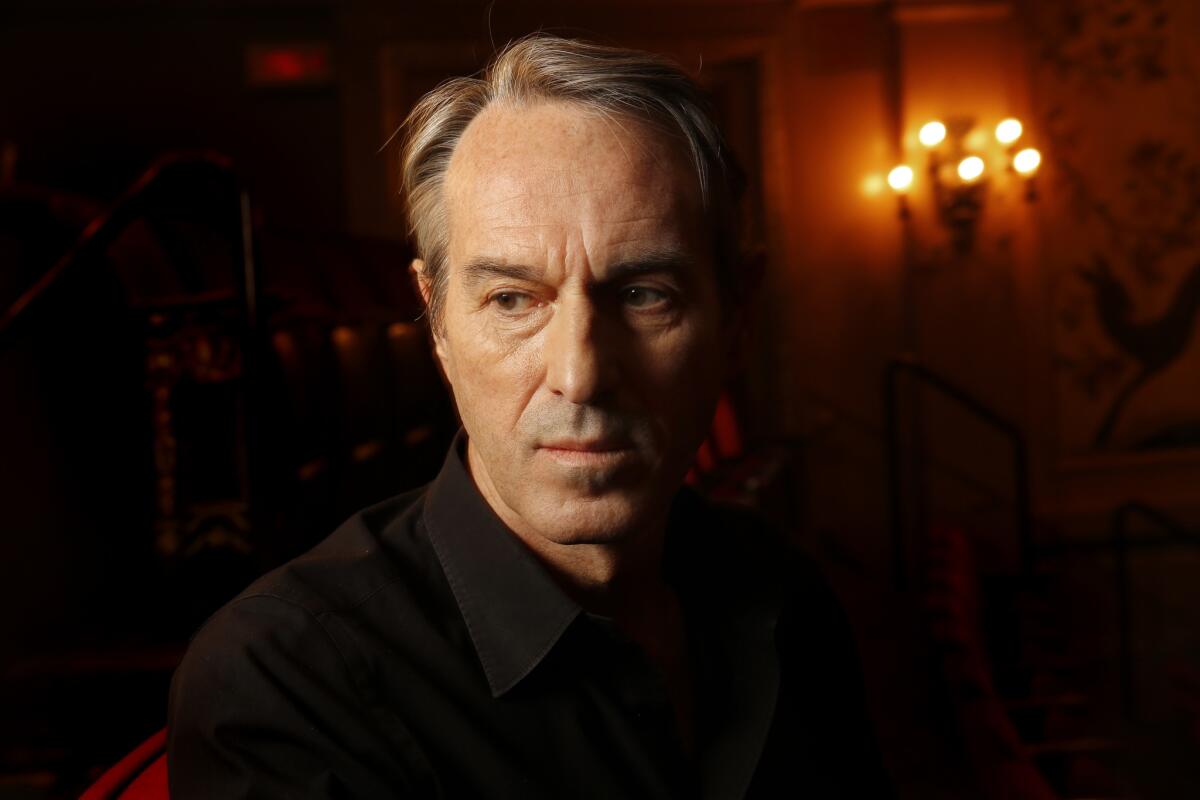

Flemish director Ivo van Hove photographed at the Walter Kerr Theater on Broadway.

Reporting from NEW YORK — For those who have been tracking the thrilling career of the Belgian-born, Amsterdam-based director Ivo van Hove, the last place you’d expect to find him working is Broadway.

But the Flemish auteur, whose radical deconstructions of modern classics at New York Theatre Workshop have brought him an ardent U.S. following, has found unexpected welcome on Broadway with two Arthur Miller staples.

Last fall, van Hove’s erotically supercharged “A View From the Bridge” opened to sterling reviews at the Lyceum Theatre for a limited run that ended in February. And he’s about to unveil his version of “The Crucible,” which officially opens March 31 at the Walter Kerr Theatre, with a cast that includes Ben Whishaw, Saoirse Ronan, Ciarán Hinds and Sophie Okonedo.

FULL COVERAGE: Spring 2016 arts preview | Exhibits | Theater | Dance | Pop music | Books

To call these high-profile offerings surprising is an understatement. If satire, as the Broadway adage has it, is what closes on Saturday night, deconstruction is what never even makes it to Tuesday.

When asked if he ever expected to be directing on Broadway, van Hove didn’t mince words in his lightly accented English: “No, never, ever.” He thanked producer Scott Rudin for this break, though he was quick to point out that he regularly works in large houses in Europe, where his aesthetic isn’t so alien from the mainstream.

Van Hove has an apartment in the East Village, not far from New York Theatre Workshop, where last fall he directed “Lazarus,” collaborating with David Bowie before the singer’s death in January. The Dutch company Toneelgroep Amsterdam, where he works closely with his production designer (and life partner), Jan Versweyveld, is still his main artistic home. But at the moment, New York and the cultural capitals of Europe are locked in heated competition for his time. Los Angeles will get its turn in September when van Hove’s production of “A View From the Bridge” comes to the Ahmanson Theatre.

Seated in the balcony of the Walter Kerr after an afternoon rehearsal, van Hove, a grayingly handsome 57, gave the impression of an enfant terrible in his distinguished middle years. His aura of European urbanity is unmistakable, but there’s nothing bourgeois about his manner.

He waved away my introductory niceties, almost wincing when I said it was an honor to sit down with him. Rhetoric, even when heartfelt, isn’t his style.

I’ve been writing passionately about van Hove’s work since his groundbreaking 1999 New York Theatre Workshop production of Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire” that starred a fierce Elizabeth Marvel as Blanche and featured a scene-stealing bathtub, in which actors were routinely dunked. I interviewed him for a Village Voice feature in 2000 on Susan Sontag when he was resurrecting her recalcitrant drama “Alice in Bed” at New York Theatre Workshop. At the end of 2014, I singled out van Hove as the most inventive director of the year for his staging of Ingmar Bergman’s “Scenes From a Marriage” — a comprehensive theatrical transfiguration that was at the same time profoundly faithful to the spirit of the original.

This balancing of textual fidelity with directorial freedom is a hallmark of van Hove’s work, and it’s the reason I consider him to be the most provocatively illuminating stage director since Bergman. Liberating his contemporary stagecraft from the obligation of surface literalism, van Hove disinters the subterranean forces that are in violent collision in the dramatic masterworks of such canonical pillars as Ibsen, O’Neill, Williams and now Miller.

Given his attraction to American literature, it was perhaps inevitable that van Hove would get to Miller. But the match in sensibilities isn’t obvious. Miller favors prose, van Hove poetry. Miller is explicitly political, van Hove implicitly so.

“Listen, I have to admit that I always considered Arthur Miller a very politically correct author who writes about good and evil in a very clear way,” he said. “But I must say I was totally wrong. When I reread ‘A View From the Bridge,’ it struck me how ambivalent this play was — and how disturbing.”

“The Crucible,” a morality tale about accusations of witchcraft among the Puritans, was written by Miller partly in reaction to director Elia Kazan’s controversial testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee. But van Hove believes that for many contemporary Americans, McCarthyism is as distant a reality as the Salem witch trials.

“It doesn’t make sense to me to go back to the birth of this story for Miller,” he explained. “When you listen to the Republican debates and when you hear how people blame, scapegoat and call one another liars, you realize that this story resonates with what’s going on right now.”

The challenge for a director, he said, is “to reinvent the play for our time.” For van Hove, this means opening “the Pandora’s box” and releasing what will be most powerful for a particular audience. A line from “A View From the Bridge” — “I just don’t understand this country” — didn’t stand out for him in London, but when staging the play in America, the issue of foreigners trying to live here and not finding a way to be part of the society suddenly presented itself to him as a master key.

Van Hove is drawn to dramas in which “the private world and the public world seem to be separate but collide with each other, creating a huge uproar and conflict.” What fascinated and frightened him about “The Crucible” was the way neighbors in this tight-knit Christian community in 17th century Salem are capable of inflicting such cruelty on one another.

“Miller knows very well that small, simple, mundane grudges can turn people into monsters,” van Hove said. “There’s a wonderful scene with Cheever, a small character but the best friend of John Proctor. He turns against him and is able to dehumanize him. And when you dehumanize somebody you can do whatever you want with him or her, because then it’s just a prop, an object, not even an animal. You can dump it.”

Van Hove doesn’t want to efface the punitive severity — the whippings, the torture, the starvation. “This really shocked me when I read the play, but in my research I didn’t see this presented as clearly.”

The word “shock” crops up quite a bit in van Hove’s conversation. He describes the experience of encountering Bergman’s films as a young man as “big shocks.” And these words aptly characterize the effect of his own stage productions, which have polarized audiences.

Not every theatergoer appreciates being shocked. But there’s another issue: The risks that van Hove takes to stun theatergoers into a new awareness of a play inevitably lead to questionable choices. (That bathtub in his “Streetcar” worked for me, but many critics found its use sensational and silly.)

Audiences have a volatile relationship with van Hove. Not only do his productions provoke antithetical reactions among cultivated theatergoers, but it’s possible for an individual to love and hate the same production, as I did his unbalanced 2004 staging of Ibsen’s “Hedda Gabler” that soaked Marvel (one of his American muses) this time not in a bathtub but in tomato juice.

Devotees have grown used to the roller coaster. (Like a baseball team that wins enough to offset the losses, van Hove is hard to quit.) Van Hove’s Toneelgroep Amsterdam production of Tony Kushner’s “Angels in America,” which came to the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 2014, was considered a revelation by those who caught the work during its brief New York run. (Van Hove admitted he was overjoyed when Kushner told him “it was the best production of the play he ever saw.”)

But van Hove’s poorly received staging of Sophocles’ “Antigone” with Juliette Binoche last year at BAM provoked quite a bit of vitriolic commotion on my Facebook feed from theater friends, a good many of whom were extolling “A View From the Bridge” a few weeks later.

The bewilderment of critics didn’t at all dampen the box office fervor for “Lazarus.” Even before Bowie’s death galvanized interest, the show (headed to London) was an impossible ticket.

Indifference might be the biggest insult to van Hove. He never plays it safe, though he was relieved to have made his Broadway debut with his Olivier Award-winning production of “A View From the Bridge.”

“Everybody thought it was going to have a hard time when the production moved from the Young Vic to the West End, but it was sold out every night,” said van Hove. “Producers in London called it a game-changer. It showed that it was possible to make adventurous work in a commercial circumstance.”

Mark Strong’s virile performance in “A View From the Bridge” anchored van Hove’s staging, but the production itself was the star. The director relishes this achievement not out of vanity but out of his deep appreciation for theater as a collaborative art.

“I’ve been working in New York now for several months, and I’ve seen Al Pacino here, Bruce Willis there,” he said. “But these are not always the productions that work best anymore. Audiences are not stupid. Al Pacino is a great actor, but sometimes he gets connected in a play that perhaps is not the right play. Theater is, at the end of the day, about the mixture of an artistic team — a fantastic play, great actors. If you can make that chemistry work, then it will be successful.”

When asked to account for his own directorial alchemy, van Hove spoke about his reliance on instinct for casting, his love of American actors (“The Crucible” reunites him with Bill Camp, Jason Butler Harner, Thomas Jay Ryan and Tina Benko), and his proclivity for rehearsing with performers who are off book so that the physical life of the drama can be fully explored.

“The text is the engine for the car to start — it’s not the whole thing,” he said. “Bodies also talk. I’m very sensitive to bodies. Where people stand, how they enter, can tell a whole story. That’s one of my specialties.”

But the most important element for him — the secret of his success, if you will — is his unique bond with Versweyveld, his partner onstage and off for 35 years. More than once, van Hove described the relationship as “intense,” personally as well as creatively. The two met in Antwerp (“city of punk, disco bars and dark avant-garde places,” is how he conjured the 1980s ambience). Although Versweyveld was a painter without a theater background, they immediately felt a compulsion to work together — and the feeling hasn’t let up.

“I was hesitant to do ‘A View From the Bridge,’ but Jan said, ‘Ivo, you have to do this.’ He pushed me to do it, and I’m so glad. I should listen more to him. I consider us a team. Of course, I’m the director. I direct the actors. But Jan has a lot to say about how I direct the actors. And I have a lot to say about the lights and scenography. We’re not really interested in which idea comes from whom. Every production for us is like a production that should be in the Olympic Games, not in the national games. We want to break the Olympic records. Sometimes you’re successful and sometimes you fail, but that’s what we want.”