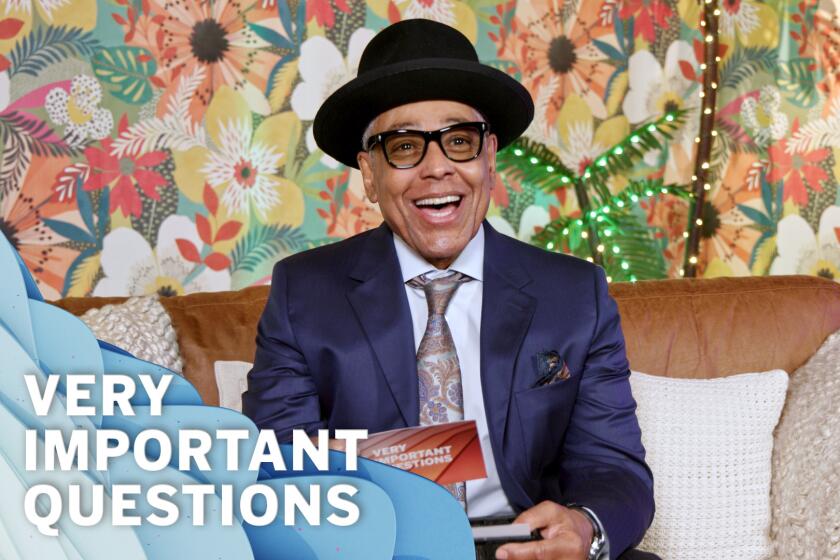

Giancarlo Esposito knows how to play the villain. In ‘Parish,’ he steps into the antihero role

- Share via

For years, Giancarlo Esposito’s performance as stoic and ruthless cartel distributor Gustavo Fring was pivotal in helping “Breaking Bad” and its prequel spinoff, “Better Call Saul,” become prime examples of antihero-centered shows. Fring’s illicit power and reign of terror established a spectrum of villainy to measure against Walter White and Saul Goodman’s moral ambiguity.

In AMC’s crime drama “Parish,” Esposito now gets to be the leading man who pushes the fine line between right and wrong. He plays Gracián “Gray” Parish, a man who is coping with the death of a son and struggling to keep his luxury car service in New Orleans afloat, when his criminal past resurfaces, entangling him with a local Zimbabwean mob family. Esposito is also an executive producer on the six-episode drama, which is based on the U.K. series “The Driver.”

“Parish” follows the release of Netflix’s “The Gentlemen,” Guy Ritchie’s stylish British crime caper, in which Esposito plays Stanley Johnston — with a “T” — an impeccably dressed, wine-loving American drug baron billionaire.

Esposito spoke with The Times about how the themes of “Parish” aligned with his own story, putting his driving skills to the test for the series, and his relationship with ambition. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

The show captures the pressures that many people feel right now — trying to make ends meet while shouldering whatever problems torment us. While few would rob a bank, start a drug empire or find themselves entangled with a mob family, many are forced into bad life choices to get by. Is there a moment in your life where you felt that kind of desperation, especially as a father?

Oh, absolutely. I had four daughters, I lived in Connecticut beyond my means — put the strike and the pandemic together. No work. This is going back 10 to 15 years. [I was] desperate; the mortgage is due on the house. I just went belly up and couldn’t get it together — beg, borrowed and stole from everyone I could. I relate to this story deeply.

When I first saw the original [series], I recognized there’s a man who’s about to collapse and cave in and be conquered. It’s reflective of some elements of my life that were real. I not only lost my house, I lost my family. I got a divorce and they went one way and I went another way. But I was so committed that, with every last penny I had, I had to take care of them; I wanted to take care of them. That was my desire, so that my kids wouldn’t have to suffer what I suffered when I was young. That was my impetus to pull out. I sacrificed everything I have to be able to get back on an even keel for them. But I carried shame for many years. I’ve been through it and came out the other end and I have a great relationship with my children and my former wife, amazingly so, but I look at myself differently. I feel differently. Because the shame that was choking me, the shame and trauma that Gray is going through, the depression that he’s in is heavy duty. This show appealed to me on all these levels because there was a relationship that I had to the element of what the character was going through. Because if you still feel that pain, it means you still have work to do. If you still have that work to do, this might help you be a little bit more honest with yourself about that part of your life that you don’t want to talk about.

How did you pull through? I’m sure the wild thoughts creep in: ”Can I rob a bank”? What do you remember about that time of your life?

You’re so astute. My former wife, the mother of our beautiful children, her family was in insurance. I found myself asking these pointed questions in a roundabout way: “How does that insurance policy work? How much am I insured for? Oh, and what are the premiums?” Just trying to be laissez faire about it because in my mind, I thought, “OK, is suicide covered?” It’s not covered. But I thought maybe I could find someone to knock me off so that my family can really make it. That’s where my mind was. The other part of it is I’m an actor, a master of disguise, a voice of physicality. So you brought it before right to the forefront: I could rob a bank. I’ve done it before on TV. I can do it in real life. You think of horrible ways and things to do that would be the least harmful for you to 1) not get caught and 2) be able to continue to live with yourself after doing something reprehensible. But then, if something goes wrong, then what are you going to do?

In our story [of “Parish”], things go wrong, they don’t go according to plan. Then you often think about, “What would I do? And where does that put my children and my family then?” So I just started to dig deeper and deeper, to figure out how to re-create myself and eventually, I started to work again and find spaces where I could find my niche. Thank goodness my family was really strong. It was really the impetus for me to start the journey of this show [years ago]. Of course, “Breaking Bad” pulled me out, and “Better Call Saul” continued it. A few years ago, I was doing five different shows as a guest artist at one time. I became very in demand and still am, juggling a lot of different balls. But what it taught me was tell your passionate story.

We were talking earlier about the points of connection to Gray. Does a performance feel truer to you when you feel like you can relate to the character?

Well, it does, but it doesn’t have to. It’s the elements of the character that I like to be able to relate to. In “The Gentlemen,” I’m playing the richest man in the world. Oh, my gosh, that’s a dream. I’d love to be the richest man in the world. I kind of know how to do that. I’m a prince. I’m a king. Most certainly, the imagination soars that you can walk through that door and be that. To me, it’s always important to have one thing, even if it’s just one little thing, that you can connect to that will open the door to 10 things.

But this project, [“Parish,”] has been different. This really reflected my heart and soul because it’s personal. It’s become so personal to me to be able to just be proud of myself for not having succeeded in my own self-annihilation. Because I’m a guy who loves life. I love my children. But I also relate to being the martyr; I relate to saving people; I relate to being a hero. But I want to live. So my gratitude runs deep because not everyone gets a shot to be who they really are on the level that I have.

In “The Gentlemen,” based on Guy Ritchie’s film of the same name, Theo James plays a British aristocrat who discovers his father’s estate is part of a weed empire run by Kaya Scodelario’s Susie.

Do you consider Gray an antihero?

Yes, partly I do, because he’s resorted to going back to an old life that’s slightly underhanded to save the above-board life he really wants. He’s equal parts of both because his intentions are good; he’s struggling against the dark intention he’s held in his life for a long time. And as we progress, knock on wood, we’ll learn about his life before his family — his wife and child. And that would be a great clue as to what he’s carrying and why.

When you’re watching someone else play the “true villain,” is it hard not to wonder how you would play a line if you were in that role?

It is sometimes because I think our true villains, many of them are stereotypical. We don’t take the time to draw them as complete human beings. I think that’s part of my success when I’m presented with playing the possibility of a villainous character; I want to make him a complete human being, not a stereotype. But we want the shorthand or we’ve resorted to the shorthand for a long time in our business, I believe. That’s what makes the difference in good film and good television that allows you to see what made that person who that person is.

The actor waited 10 years to make his TV directorial debut. He spoke to the Times about getting the call and key creative choices in ‘Axe and Grind.’

We obviously need to talk about the driving in “Parish.” I long to get on a highway and just go pedal to the metal even though it would terrify me. I know you’re a car person. How much of it were you able to do and how was it to lean into that?

It was really wonderful. I think as a driver who has taken a couple of driving courses — not as much as the stuntmen take — when they asked me to come down and show them (it’s happened on [a few] movies: “Maze Runner,” I did a moment driving in that movie; “Harley Davidson,” “The Marlboro Man”), I can spin this pickup truck around or come and show us how you could stop on a dime if that rock is the camera and it’s right in front of you. I have to prove it. And when they asked me to do the same for “Parish,” take the driving course with them and learn a reverse 360 and practice spinning the car around and weaving, I thought, “Oh, I know how to do that.” But it takes practice. Even if you know how to do it, you need a refresher course. I drove my butt off on “Parish.” I don’t want to say too much because there were a few moments where I’ll just say I was chided. I did what you wanted to do on the very narrow streets of New Orleans. I learned a lot about my own self-control. I learned a lot about my reflexes and being safe. Andy [Dylan], our stuntman, was amazing. We had amazing car people, we had amazing first ADs [assistant directors] who were able to guide me, and I was able to push it to a limit, but not over that limit, and feel as if I still had control.

I do want to ask you about “The Gentlemen.” You play Stanley Johnston, who occupies the opposite end of the economic spectrum to Gray in “Parish.” How was it navigating that elite and perilous world?

Oh, so much fun for me. I wanted to be very specific about who Stanley was. I really wanted to research and work with Loulou Bontemps, who had such great clothing design [on the show]. It put me in a space where I felt like I was the king. The king doesn’t worry about anything. The king worries about his presentation and takes care of his business. It allowed me, through my conversations with Guy Ritchie, who was familiar with a person — African American, as well — who had that kind of stature in our world, [to] realize that that was always a dream of mine; and I could make it possible in this reality, in this show “The Gentlemen.” What I loved about it, is it’s a way of carrying yourself. My character, Stanley Johnston — with a “T” — knows all about British history, he knows about their culture and their rulers, he knows about their politics. He’s educated himself because he’s fascinated with that culture. It allows him to have an upper hand on being ahead of what he’s about to offer you. He’s also persistent. And he also has all the means in the world. There’s a lightness about Stanley that I really enjoyed incorporating into the wolf in sheep’s clothing.

Let’s take a step back. Your mother was an opera singer and your father a stagehand. You’ve been acting since you were very young, making your Broadway debut when you were 10. Did you feel ambitious as a kid?

I felt ambitious to get out of the situation I was in. I didn’t like my home life. My mother and father — leading up to their divorce — weren’t nice to each other. I had a brother who dominated my personality, in that he was the stronger one. I was always reluctant to show who I was. I chose that path. I felt like I had a vision for my life but didn’t know quite what it was. I think the ambition was to be the best I could be. I love the story of [explorer Ernest] Shackleton. I loved adventurers. And I think that’s what led me to be an actor. Because in my acting life, I feel like somewhat of an adventurer. I’m in this world where I’m navigating something I don’t know — and it’s unsure and unsafe and edgy, and I’ve got to find a way to survive in it and to move forward. I have these Giancarlo-isms, one of them is: If you don’t know where you’re going, you’re never gonna get there. So it’s like, choose something, otherwise, the choice gets made for you.

So the stories I want to tell, and I continue to tell, there’s something about me sharing them on a personal level that allows someone sitting at home, eating Cheerios or pork and beans — like I was at 29th and 8th Street, my mother, brother and I were sleeping in one bed that rolled into the middle, we had plastic on the windows in the middle of the winter because it had no glass, [it] was a flat pass — and sees this interview or reads me in the L.A. Times and one thing, who knows what it’ll be, in this conversation it will allow them to go: “Oh, wait a minute. I’m not going to stop, I’m going to keep trying.”