‘Lois & Clark’ at 30: How the Superman series led to a new era of superhero TV

When Mark Pedowitz, chief executive of the CW, left the network last year, some fans of worlds where men wear masks and capes and women can fly saw it as the death of, well, Superman.

Under Pedowitz’s reign, the basic cable channel went from a harborer of flashy teen dramas like “Gossip Girl” to the headquarters of series based on comic book characters from the DC Universe — ones that happened to be owned by then-parent company Warner Bros. (In 2022, Nexstar acquired a controlling stake.) Shows like “Arrow,” “Supergirl,” “The Flash” and, the lone survivor, “Superman and Lois,” are all produced by partners Greg Berlanti and Sarah Schechter’s Berlanti Productions and all rely on a solid formula of stories about superheroes saving the world mixed with the office romances and familial dramas associated with nighttime soaps.

But 30 years ago, another TV show helped lay the groundwork for these types of superhero series: ABC’s “Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman,” which premiered Sept. 12, 1993. It saw comics’ infamous power couple as 20-something reporters working together to investigate stories for their esteemed newspaper, the Daily Planet, and take down corruption in the city of Metropolis. In reviewing the pilot, then-Times TV critic Howard Rosenberg described it as “relentlessly witty” and “a series that flies.”

The less-than-rhapsodic fall season continues to unfold Sunday with a loud confrontation that will help determine which network takes second place in the ratings that night behind “60-Minutes”-led CBS.

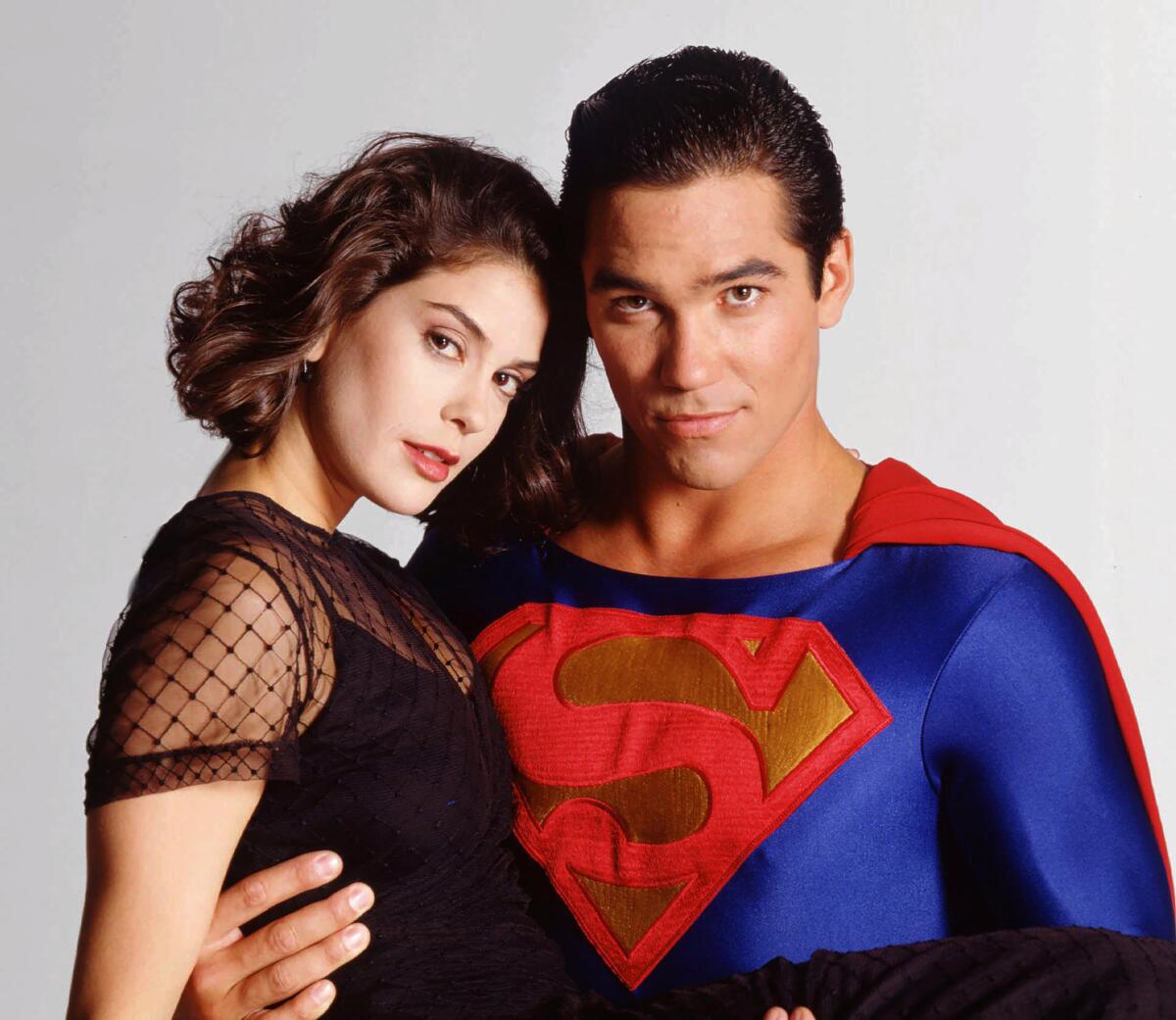

Starting with its title, creator Deborah Joy LeVine wanted to make a statement that this show was not like past TV and film interpretations of these characters. In her version, she says now, she wanted investigative reporter Lois Lane (Teri Hatcher) to be “smart and sassy” and “an equal” to Dean Cain’s Clark Kent — a mild-mannered reporter fresh off the bus from Smallville who just happened to have superhuman powers.

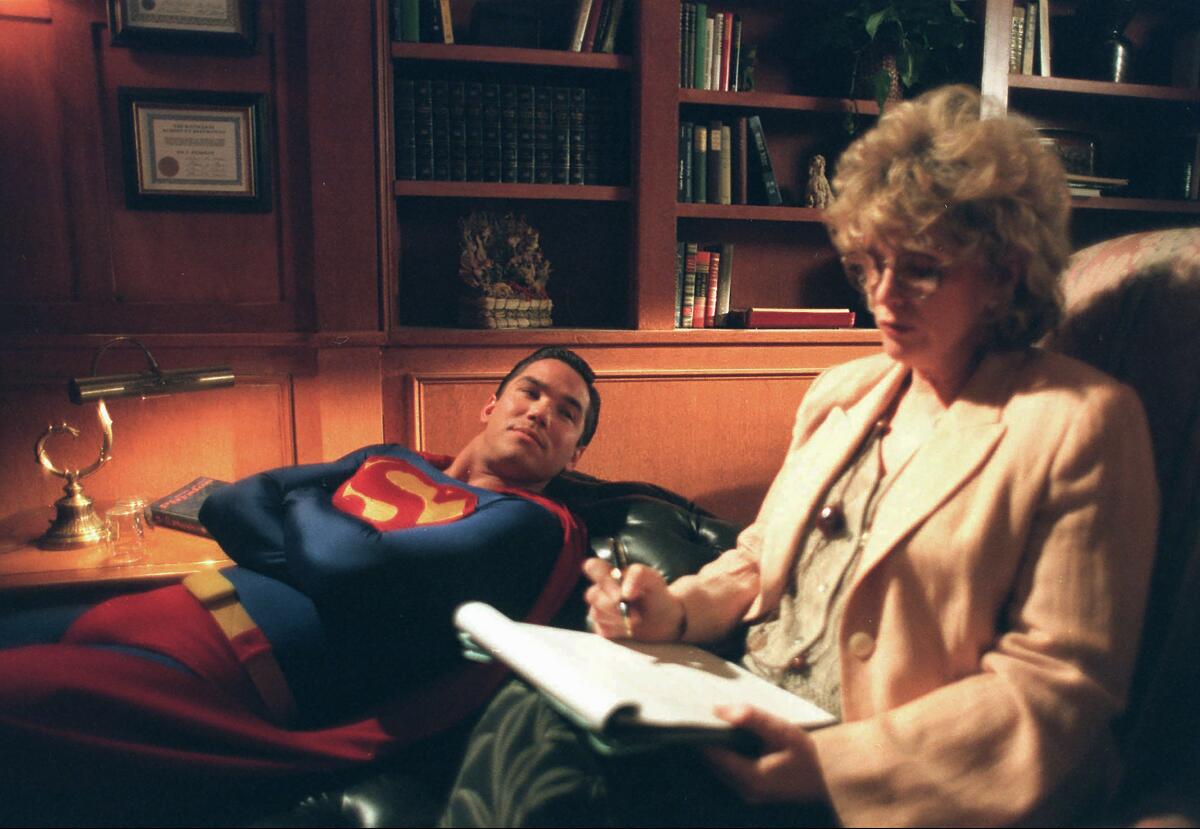

“I didn’t want to make him perfect either,” LeVine says. “Superman, at that time, could do no wrong. Since then, they’ve gotten a lot more sophisticated about it. But, at that point, they hadn’t and I wanted to show flaws as well as attributes.”

Eventually running for four seasons, “Lois & Clark” was never a ratings behemoth. But it did show that you could take the live-action superhero formula out of the kids arena (see: the Adam West-starring “Batman” and the George Reeves-starring “Superman”) — or even the procedural and action spaces like “The Incredible Hulk,” which starred Bill Bixby and Lou Ferrigno, and John Wesley Shipp’s “The Flash” — and find an adult, mainstream audience.

And while superhero films released before the early ’90s, such as “Superman” and the Michael Keaton-starring “Batman” movies, had proved to be box office successes, CNN media critic Brian Lowry notes that “Lois & Clark” fit in with shows such as the Robert Hays series “Starman” (which was a follow-up to the 1984 movie of the same name) as a “genre of series that were built around recognizable titles but were more scaled-down, character-driven versions of them.” He remembers one executive saying at the time that “Lois & Clark” was “aimed at women; not aimed at comic book fans” — which, according to Lowry’s translation, meant “lonely, middle-aged guys.”

From George Reeves to the new “Superman & Lois,” the superhero and his alter ego, Clark Kent, have thrived most on TV’s patient character development.

LeVine gave the edict that instead of modern-day costumes, Lois should wear 1940s-style broad-shouldered skirt suits and suggested to Hatcher that she have a more conservative and wake-and-go hairstyle (the actor came to work the next day with her long hair lopped off).

Storylines in the first season involved everything from the exploitation of abandoned kids, which mirrored Clark’s own questions about where he came from, to going undercover at a gin joint to take down the mob (where Hatcher sang in a sparkly dress). There was also a “Big Bad” central villain in the form of John Shea’s devilish and debonair Lex Luthor, whose own narcissism and obsession with Superman led to his ultimate destruction.

“I didn’t really want to do the ‘Superman’ of the 1950s and ’60s where they just sort of put on an outfit and save the day,” LeVine says. “I wanted to get more into the psychological factors going on with Clark Kent and how Lois was being a single woman and how crazy [and] f— up Lex Luthor was and all the interesting things he did.”

She says she wanted to examine “Lois’ life: Here she was, the single woman, and she meets this guy who turns out to be a superhero. What the hell does that do to you?”

But there’s also a playfulness to the show. LeVine’s favorite scene in the pilot is a montage of Clark, with the help of his mother, Martha (K Callan), testing out supersuits. It’s scored to Bonnie Tyler’s “Holding Out for a Hero” and has references to other superheroes’ costumes. Later, when the public spots him in his costume for the first time, they wonder, “Is it a bird?” and “Is it a plane?” before someone responds, “No, Just a guy in a pair of tights and a cape.”

“In the back of my mind, I was purposely [not] doing a superhero show,” LeVine says. “I was just doing a really good drama. And I think that that influenced me.”

Executive producer Robert Butler says that, in directing the pilot, he and cinematographer Chuck Minsky specifically avoided what Butler calls the “jelly bean colors,” like the bright reds of other superhero shows. Instead, he says, “We wanted a softer light to make it look more naturalistic.”

They also had to capture the energy of the flirtatious banter between Lois and Clark as well as the fast-paced cross-talk among all the journalists at their newspaper.

“I discovered somewhere during my directorialship that restlessness introduces reality,” he says. “If your cast is restless, at the water cooler or anything, there seems to be a transfer that [audiences] understand them or they’re more relatable. And the fact that the dialogue is fast-paced is certainly you joining the club.”

LeVine left the show at the end of the first season over creative differences with Robert Singer, who had directed episodes in the first season and stepped in as showrunner. One of the earliest changes was hiring visual effects supervisor Mark Zarate, whom Singer credits for pushing what was possible for that medium at the time. But he restaffed other parts of the production, from the writers room to replacing Michael Landes with Justin Whalin as Jimmy Olsen, Lois and Clark’s newsroom buddy.

Like LeVine, Singer says he didn’t come onto the show as what he calls a “comic-book person.” He says he instead aimed to “put out a bit of drama within the context of what the show could be without paying too much attention to that world.”

“We knew we had gold with the two leads and [so we did] whatever you can do to make that relationship interesting and let them really carry the ball.”

Without a main villain like Shea’s Lex, Singer and his writers got creative with specific kinds of baddies as well as the actors who played them. Drew Carey played a shady real estate agent who accidentally summons the ghost of a dead housewife (Kathy Kinney). Peter Boyle played a member of Metropolis high society who was really a crime boss. Tony Curtis played a mad scientist who was creating frog-eating clones of powerful people. And in one memorable episode, Lane Davies played a man from the future who point-blank asks Lois about the show’s frustrating central conceit: How can such an intelligent woman not realize that Clark is Superman? (Too bad for her that her memory is wiped at the end of that episode and she has to go back to not cracking his disguise of glasses and a different hairstyle.)

“I think we injected a little more humor into it than just the Big Bads were bad and that they were evil and they pose a real threat,” says Singer, whose credits also include the long-running CW fantasy series “Supernatural,” which also had stand-alone mysteries and drawn-out investigations. “When you’re writing these shows, it’s important to not make them cookie-cutter, cardboard villains and give them a life of their own. And when you have a blank canvas, it encourages you to come up with original villains.”

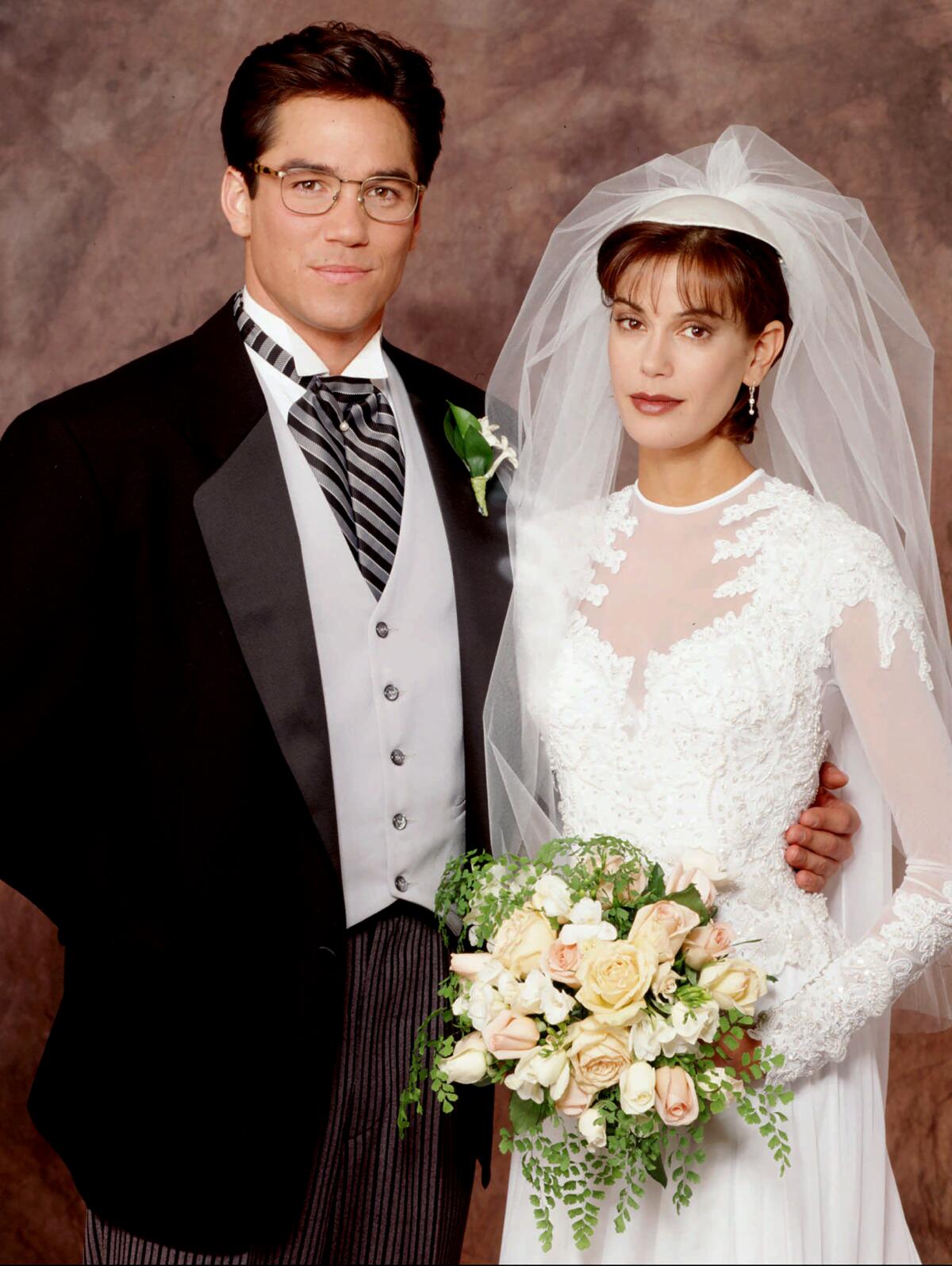

And, as opposed to today’s Marvel Cinematic Universe, which intricately intertwines plots and characters from all of its forms of media, Singer says, “We really didn’t have much congress with the comic-book people.” However, DC Comics did release “Superman: The Wedding Album,” a comic that features Lois and Clark tying the knot at the same time that the couple married on the show — both worlds finally putting an end to this will they/won’t they saga.

Singer says now that the couple’s nuptials on the show probably wasn’t “the wisest choice” because, as is the problem with so many long-running series, there wasn’t anywhere else to go after that.

Otherwise, he says he’s proud of the work. “I thought we were doing pretty well. I thought we had some really good characters and that there was some interesting stuff that we did.”

It also ended by keeping the ethos of LeVine’s forward-thinking vision: In the final season, Lois and Clark’s mentor, Lane Smith’s Perry White, is promoted and Lois takes his job as the editor of the Daily Planet. She gives it a go but realizes she’d rather be a reporter — and Clark’s equal.