Commentary: Michael Jordan docuseries ‘The Last Dance’ is more than a TV show. It’s a cultural event

In 1998, on the home stretch of his sitcom’s final season, Jerry Seinfeld submitted to a courtside interview about the era’s premier sporting dynasty.

“The similarity between ‘Seinfeld’ and the Bulls?” he repeats for the camera, before heading to the locker room to greet the game’s star, Michael Jordan. “The show of the ‘90s, the team of the ‘90s.”

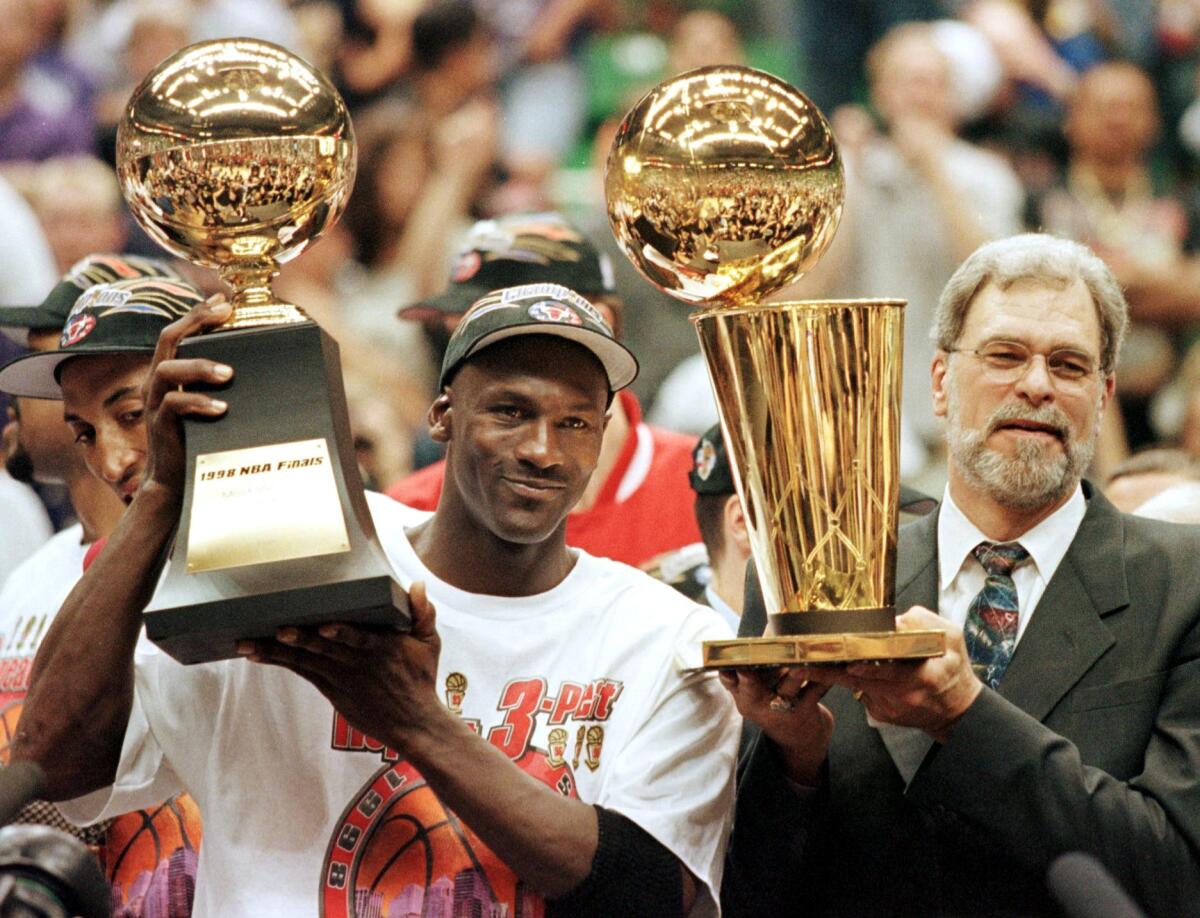

By the time spring turned to summer, his comparison would be borne out: Love it or hate it, the series finale of “Seinfeld” became an epochal TV event (76.3 million total viewers), and Jordan led Chicago to its sixth NBA championship in eight seasons before retiring, not for the last time, at age 35.

While it’s the latter that forms the backbone of Jason Hehir’s extraordinary new docuseries “The Last Dance” — a co-production of ESPN, the worldwide leader in sports, and Netflix, the worldwide leader in just about everything else — it’s the series’ attention to Jordan’s place in the broader cultural firmament that suggests its ambition, and its achievement.

Woven from archival video, in-depth interviews with Jordan and his contemporaries, and never-before-seen footage shot by a camera crew embedded with the Bulls for the 1997-98 NBA season, “The Last Dance” jumps between the basketball dynasty’s farewell tour and the arc of Jordan’s remarkable career, with detours into the lives of teammates Scottie Pippen and Dennis Rodman and coach Phil Jackson.

In the process, its multi-layered treatment of what sportscaster Bob Costas calls “one of the most consequential teams in American sports” emerges as the latest in a line of TV series, fiction and non-, to reconsider that decade and its defining figures: the post-Cold War, pre-9/11 period in American life that was the monoculture’s last dance too.

Live sports are on hold until the threat of the virus outbreak has passed. So we asked a sports fan to recommend TV shows that provide a sports fix.

It seems at once a cruel caprice and an eerie reminiscence, then, for the 10-part, five-week event to arrive at a moment marked by the shared experience of the COVID-19 pandemic, in which the vast majority of us are staying home to halt the spread of the coronavirus and the world of sports is in suspended animation. When the first two episodes of “The Last Dance” premiere on Sunday, they will of course compete with other new TV shows, streaming movies, video games, beloved albums, countless books, not to mention TikTok dance challenges, stress baking, doomscrolling, sex. But for the diehard (and fair-weather) sports fans missing March Madness, The Masters and Major League Baseball’s opening day, the series may feel like manna from heaven: For the time being, “The Last Dance” is one of the only games in town.

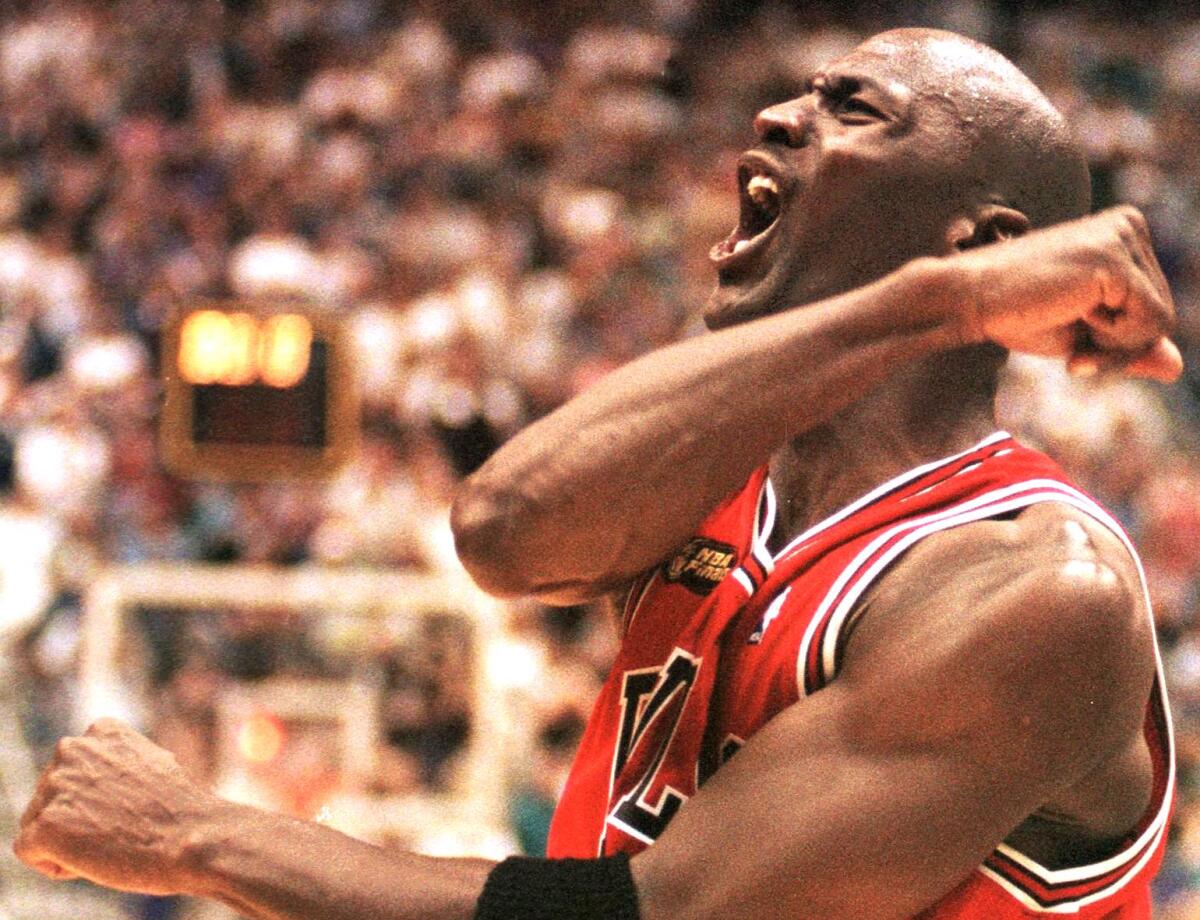

For anyone capable of feeling a flutter at what one thickly accented Chicago fan calls Jordan’s “poetry in motion,” there’s no shortage of fodder. In the absence of postseason fever, “The Last Dance” employs the star’s on-court fireworks to approximate the playoffs’ particular intensity — with his outrageous, record-setting 63 points against the ’86 Boston Celtics, for instance, or with the buzzer-beater known as “The Shot” against the ’89 Cleveland Cavaliers.

But the series — reliant as it is on the “SportsCenter” segments and Finals broadcasts of yore — is as much about the media landscape Jordan swept into as his athleticism or competitive drive. Even its rendering of the locker-room drama swirling around the ‘97-98 season has a familiar tabloid feel, like a purloined special of “Inside Edition” in which the Bulls come to reflect the tropes of fiction: the epochal hero, his trusty sidekick, the misunderstood rebel, their inscrutable sage. (There’s even a villain of sorts in general manager Jerry Krause, though he is the most underdeveloped, and thus unsatisfying, of the central figures. Krause died in 2017.)

Hehir and company lean into this angle from the outset, with an operatic score and a title sequence that emphasizes “back-stabbing” over points and rebounds; to wit, one of the most compelling subplots in “The Last Dance” is the bitter rivalry between the Bulls and the Detroit Pistons, which can be understood even if your primary point of reference is Sharks versus Jets. For every comparison of Jordan to Babe Ruth or Muhammad Ali, there is another to Oprah Winfrey, Barack Obama, the Beatles, the pope. McDonald’s sponsors an international basketball exhibition in Paris. Spike Lee appears as Mars Blackmon to promote Nike’s Air Jordans. Gatorade commands us to “Be Like Mike.”

We polled more than 40 TV critics and journalists, inside and outside The Times, on the best TV show to binge while stuck at home.

“It was the first time that sports were being sold in a cultural way,” NBA commissioner Adam Silver says of The Dream Team’s dominant performance at the 1992 Olympics, comparing the U.S. export of sports to that of fashion or music. “You were selling Americana.”

And what is modern Americana if not salesmanship itself? As I once wrote of Jordan’s friend and fellow sports icon Tiger Woods, our nostalgia for the monoculture’s mid-’90s zenith — in which a sitcom’s finale could attract fully one quarter of the U.S. population, and Game 6 of the NBA Finals more than one-tenth — cuts both ways. One person’s “fracture” or “fragmentation” is another’s hard-won time to shine.

“The Last Dance” trades on this nostalgia, and given the strange, fraught moment of its debut, may do more than that: It is not only an ode to the years in which “everyone knew Michael Jordan,” as journalist Willow Bay says in the series, but also an attempt to recapture their magic. As such, while Hehir’s vision is not terribly sophisticated when it comes to race or politics or the long arc of social history, it is extraordinarily perceptive about celebrity — what makes it, what breaks it, what shapes its character and magnitude. Without downplaying Jordan and his teammates’ remarkable prowess, the series tacitly acknowledges that fame, even in sports, is a function of framing, of timing — that what the show of the ‘90s and the team of the ‘90s had in common, as Seinfeld intuited, was first and foremost the ‘90s.

The nature of change means the phenomenon of Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls, like that of the “Seinfeld” finale, is unlikely ever to be replicated. But it can be relived, or at least revisited, in the cultural time machine of “The Last Dance.”