How the ‘cool aunties’ of pop culture flout the growing restrictions imposed on women

- Share via

In the great taxonomy of aunts in popular culture, there are stern aunts, maternal aunts and cruel aunts (like malevolent Aunt Petunia in the “Harry Potter” tales). But these days one particular category of aunt appears to be on the rise: the cool aunt.

You’ve probably encountered some version of the cool aunt online or IRL. She is also known as the rich auntie, the eccentric aunt, the savvy aunt, the sexy aunt, the wild aunt or the PANK, a.k.a. Professional Aunt No Kids (because capitalism will turn any phenomenon into a market segment). The cool aunt often carries herself with an air of glamour and authority — Edna Mode of “The Incredibles” has strong cool aunt energy. She’s also a bit of a rule breaker. It’s the cool aunt who will take you to a dirty ballet at 14 and let you have your first sip of Champagne.

These days, cool aunts seem to be popping up everywhere — and the timing is likely no coincidence. At a moment in which women’s bodily autonomy is being constricted by a slew of anti-abortion laws, the cool aunt offers a model of self-assured sexual independence. The cool aunt also provides a critical alternative to the limitations of the nuclear family. For queer teens, a cool aunt can be a source of emotional and material support.

“Aunts offer alternatives,” says Patty Sotirin, author of the 2013 book “Where the Aunts Are: Family, Feminism and Kinship in Popular Culture.” “They offer different ways of connecting us and give us a sense of other possibilities. These days, they are so important.”

When we should be celebrating a half-century of progress, it is depressing to be grieving instead for rights that have been withdrawn.

In December, comedian Ego Nwodim appeared on “Saturday Night Live’s” “Weekend Update” as a character called Rich Auntie With No Kids, armed with a martini, a fur stole and a dismissive attitude toward maternity. A few weeks later, Universal Television announced that the “Rutherford Falls” creative team of Sierra Teller Ornelas and Jana Schmieding were developing a comedy series called “Bonnie” about a cool aunt who returns to the reservation to help raise her brother’s children.

My social media feeds as of late have been awash in cool aunt memes — both in English and Spanish. On Instagram, there are nearly 182,000 posts tagged #richauntyvibes, featuring women looking fashionable as they lead their best life, while on TikTok, hashtags like #coolaunt and #cooltia turn up thousands of videos with millions of collective views. Among my favorites is one of a series of posts by Fernando Pacheco, an architecture student from Venezuela who goes by the handle @fertris.7, that shows him posing as a glamorous tía cool — complete with large handbag and even larger sunglasses. The aunt he portrays is a woman “who is modern, who is always going to be fashionable,” he tells me. She is “a personality who is down for anything.”

But the cool aunt is much more than her trappings. She is a woman who defies the limitations of gender proscribed on women — and therein lies the appeal. “With the mother, you have all of these cultural expectations,” says Sotirin. Mothers are expected to be wholesome and nurturing. “But not the aunt. You don’t have the same thing with the aunt.”

The archetype of the cool aunt is hardly new. In the 1958 comedy “Auntie Mame,” for example, Rosalind Russell played a delirious bohemian who assumes the care of her 10-year-old nephew after the sudden death of his father. (Among other things, she schools him in the art of making a martini “because knowledge is power.”) In more recent years, the cool aunt has been transformed into an economic niche as marketers have set their sights on the disposable income wielded by an increasing number of childless women. Lifestyle sites such as Rich Auntie Supreme peddle auntie-themed merch while a variety of auntie-themed podcasts offer everything from relationship to financial advice.

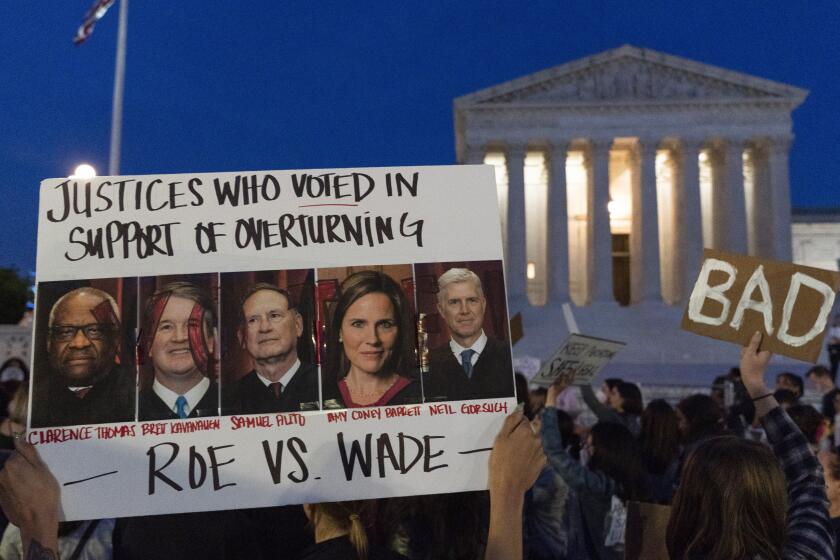

But what makes the cool aunt such a meaningful figure right now is that her increasing prominence lands at a time in which women are losing hard-fought gains. Last year, the Supreme Court overturned Roe vs. Wade, which has resulted in severe restrictions to a woman’s right to abortion in almost two dozen states. Last month, a study published by the Journal of the American Medical Assoc. estimated that there were more than 26,000 rape-related pregnancies in Texas in the 16-month period since restrictions went into effect, essentially turning women into birthing vessels against their will. (Texas offers no exceptions for rape or incest.) Recently, a woman in Ohio faced potential criminal charges for how she handled a home miscarriage. (Thankfully, the grand jury deciding her case declined to indict her last month.)

Meanwhile, an ascendant right wing is busy flogging the concept of the nuclear family — heterosexual, natch — with men as breadwinners and women maintaining the home and raising children. Prominent on social media these days are “tradwives” (slang for “traditional wives”), who take to TikTok in flowery dresses to extol the virtues of home-cooked meals and submitting to their husbands. What two consenting adults do in the privacy of their home is nobody’s business but theirs. (Though the highly aestheticized frontier look can be unsettling if your ancestors happened to be on the receiving end of Manifest Destiny.)

By not having children, I gave myself the space to consider what I prefer to do as opposed to the “shoulds” set before me by the church, gender roles and society.

But, as the feminists say, the personal is political. And tradwives are often used by right-wing media to drive a wedge between groups of women, pitting feminists against homemakers in the culture wars. The phenomenon also fetishizes “traditional” gender roles, creating a hard binary between men and women, between who occupies the public sphere and who does the child-rearing. Never mind that, as English demographer and anthropologist Rebecca Sear has written, family bonds and the raising of children across societies are generally not confined to an isolated family unit, but instead depend on a complex web of relationships in and out of the family.

The figure of the cool aunt cheekily subverts the controls imposed on women — which is probably why she is currently a darling on social media.

“When you have this pullback and restriction,” says Sotirin, “you have to have something — other possibilities, other ways to empower ourselves ... The auntie is the perfect model for that.”

Moreover, within family structures, cool aunts serve a function that goes beyond simply being a sassy role model. “Where do you learn about sex?” Sotirin says. “If you have a question and it’s too embarrassing to ask your parents, you ask the cool aunt.”

It’s a phenomenon that is drawing the attention of scientists. A longitudinal study published December in the sociology journal Socius, which followed 83 LGBTQ+ youth in California and Texas over two years, reported that “aunts (including heterosexual aunts) can challenge cisheteronormativity, can serve as an important social support network for youth and can serve as housing support for young people.”

Los Angeles feminist artists such as Constance Mallinson and Merion Estes laid the roots of Pattern and Decoration, which challenged Minimalism.

Sotirin says this is something she has seen in her own research on “aunting.” Queer youth, she says, might find acceptance with a cool aunt that they don’t get from their parents. “I interviewed a student who is gay and belonged to a religious community, but he talked to his aunt and, through his childhood, she supported him.”

Pop culture has turned the cool aunt into a cartoon character: a wearer of large sunglasses and bearer of designer handbags. Like so much in our culture, it’s the acquisitiveness that gets highlighted. But cool aunts are much more than their accessories. (I say this as a cool aunt who doesn’t own a single designer anything but will take you to a dirty ballet.)

Cool aunts may be glamorous. But, more importantly, they are subversive — a powerful statement of noncompliance to chauvinist systems of control.