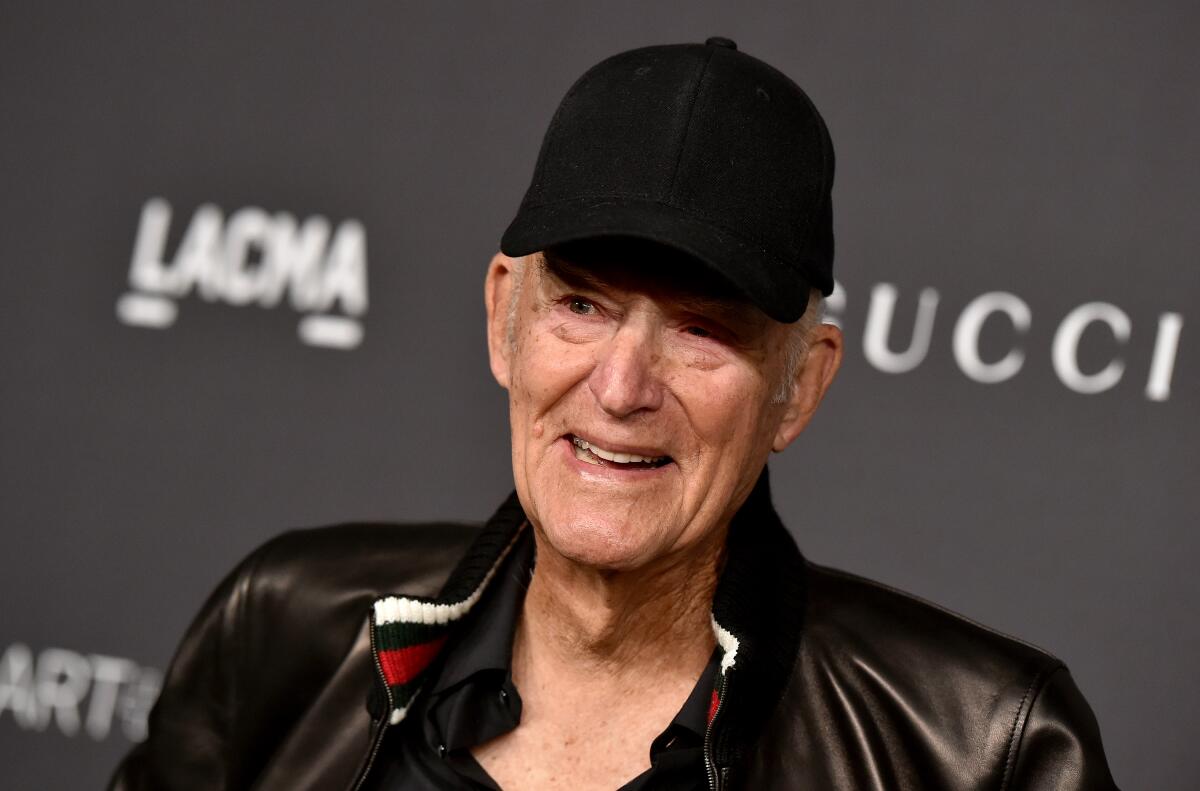

Robert Irwin, pioneer of Light and Space art who designed Getty’s Central Garden, dies at 95

Dressed unassumingly in jeans, a chambray shirt, work boots and a baseball cap — the sober worker’s uniform of a typical mid-1970s male artist — Robert Irwin would stride into the university seminar room wearing one additional enhancement: a sly and blissful grin.

This will be a pleasure, the smile silently signaled to the small assembly of students, all prepping for an imagined future as artists or art historians.

A casual seminar format was conceived by Irwin, one of the most important American artists of the late 20th century, who died on Wednesday in San Diego at the age of 95. Irwin’s death was confirmed by Pace Gallery, which represented the artist.

Irwin was the leading figure in Light and Space art that emerged in the 1960s, the only wholly original art movement to begin in Los Angeles. His seminar aim was evangelical — to spread an artistic gospel to schools across the country. Like his paintings and installations, forged in a city historically identified with popular culture, the unusual project embraced a sense of being outside art’s institutional norms.

The presentation had less to do with traditional lectures in college classrooms than it did the campus teach-ins of the recent Vietnam War era or the sweeping, crowd-pleasing intellectual rambles of an R. Buckminster Fuller, where seemingly unrelated elements would suddenly reveal themselves as an interconnected whole. Soon these college kids would be engaged with Irwin’s wide-ranging, largely self-taught intellect on a surprising tour through Western art of the previous five or six hundred years — culminating, of course, with his own radical work.

Irwin didn’t project slides of paintings and sculptures on a classroom screen to illustrate his points, historical or current. The omission, rare for a graduate student seminar, was in keeping with his stubborn refusal to allow publication of photographs of his stripped-down abstract paintings, sleek acrylic sculptures and room-size installations. (He later lifted the ban.) The works he had been making since 1962 weren’t exactly photogenic, assembled from modest materials like translucent plastic scrim, solid planes of color or black electrical tape. But you were either in the presence of the actual art or you weren’t, his reasoning went, and no photographic representation of it could help but interrupt — and corrupt — the perceptual experience.

Same with art history. In his seminar, Irwin chronicled the changing narrative of primary values within Western painting since the Middle Ages. The red blood of a crucified Christ became the red robe of the king, which became the red cassock of a church cardinal, which became a merchant’s red cloak, which became a handmaiden’s red shawl, which became red poppies dotting a field, which became an artist’s red studio, which became a red rectangle, which became — lastly — just plain red.

Color was pure abstraction materialized — light experienced in space. The centuries flew by, finally arriving at a dramatic ending: In the modern world, the clarity and depth of individual aesthetic experience had become, for Irwin, art’s primary value.

‘Robert Irwin: A Desert of Pure Feeling,’ a new documentary premiering at DOC NYC, chronicles the long, often unlikely career of the 94-year-old artist.

With that, Irwin had explained why he stopped painting in 1966 to begin experimenting beyond the conventional picture frame. Perception crystalized through light within the complex structure of a specific space, home to its merit and meaning, was the critical consequence of Irwin’s artistic practice.

The art he would produce over the next 50 years took a stunning array of forms. It might be a seemingly empty but ethereal storefront on a shabby street near Venice Beach, an extravagant and ever-changing garden in a ravine between buildings at Brentwood’s Getty Center, or a nearly indescribable built environment for shadow and light constructed atop the ruins of a defunct Texas military hospital.

Irwin was born in Long Beach on Sept. 12, 1928, to Goldie Florence Anderberg, a homemaker, and Overton Earnest Irwin, who worked in the local shipyards. His sister, Pat, was born the following year. The family soon moved to a modest stucco house on South Verdun Avenue in a working-class Los Angeles neighborhood at the southeastern edge of Baldwin Hills, just north of Inglewood.

Irwin described his childhood as sunny and uneventful, marked by ordinary kid things like working after school selling the weekly magazine Liberty door-to-door, washing dishes in neighborhood coffee shops or ushering at movie theaters to make a bit of pocket money. While at Dorsey High School he became a keen competitor in swing-dance contests, a national craze in the late 1930s and early ’40s, racking up prizes for his exuberant skill at the Lindy Hop.

His hobby was customizing old cars, honing their component parts with painstaking precision, even if those things couldn’t be seen without lifting the hood.

“The car was your home away from home,” he would later tell author Lawrence Weschler, whose “Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees” (1982) remains the artist’s standard biography. (First published in multiple parts in the New Yorker, the book was reissued in an expanded version in 2009.) The fastidiousness with which Irwin detailed a ’32 roadster or lowered a ’34 coupe eventually would be cited as instigating the meticulous exactitude he brought to abstract paintings in the 1960s, room-size perceptual installations in the 1970s, outdoor environmental sculptures in the 1980s and the sweeping design and lavish plantings of the 134,000-square-foot Central Garden at the Getty Center, which opened in 1997.

In June 1946, immediately after high school graduation, a rather aimless Irwin joined the Army, enticed by a vague awareness of promised G.I. Bill benefits down the road. Stationed unhappily in postwar Germany, he signed up for three years of stateside U.S. Army Reserve service that would cut his European tour of duty short. The benefits came in handy when, back in L.A. in 1948, he enrolled at Otis Art Institute — the first of three art schools he briefly attended (the others were Jepson and Chouinard, now CalArts).

Equipped with a natural drawing ability, he had drifted into art school mostly to learn techniques. Irwin churned out conventional genre scenes and pictures of friends, employing gently Expressionist and mildly Cubist skills learned from such popular teachers as Howard Warshaw and Rico Lebrun.

Once he was getting skills under his belt, he wasn’t sure what to do with them. Becoming an artist wasn’t exactly planned.

Periodically, Irwin headed back to Europe to knock around a bit.

Speaking no foreign languages, he spent most of his time alone. Paris, Madrid, Florence, Amsterdam — for something to do, he began to drop into churches and museums, which he hadn’t bothered with during his Army stint. Almost no such opportunity to see a wealth of historical European art had existed in Los Angeles.

Paradoxically, the more examples of Old Master and 19th century paintings and sculptures that he saw, the less interested he became in learning their lessons. On a whim, he hopped a boat to the small bohemian island of Ibiza, off the coast of Spain in the Mediterranean. There, he promptly underwent an experience that would change everything.

Robert Irwin’s ‘unlights’ make use of fluorescent tubes, colored gels, electrical tape — and not a spark of electricity at the gallery Kayne Griffin.

Like St. Paul retiring to a cave in the Egyptian desert or the Zen Buddhist hermit Ryōkan withdrawing to a placid Japanese monastery in the mountains of Honshu, he rented a tiny, lonely cabin near a remote fishing village. Without intending it, he conversed with almost no other human beings for the duration of his stay. Months passed, and seasons. Save for the rustlings of the environment, all was relative silence.

“I realized I was in the 20th century,” he later explained to Weschler, recalling the simple outcome of the isolated experience. “And I wasn’t at all interested in historical forms.”

Back in Los Angeles, he wasn’t sure how to proceed. He married Nancy Olsburg in 1956 (they would divorce, remarry and divorce again) and, to pay the bills, headed to the Hollywood Park racetrack to become a professional gambler.

Later, in the 1980s, after dustups over the precarious launch of L.A.’s new Museum of Contemporary Art, where Irwin had been among the most vocal members of the founding Artists Advisory Council, he would do something similar. Wounded by personal attacks, he left the city for Las Vegas and earned a living at the casino sports books. He told no one of his departure and left no forwarding address. When the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation chose him in 1984 for one of its first two fellowship grants awarded to artists, they had trouble locating him.

MOCA would organize a retrospective of Irwin’s work in 1993. The show traveled to museums in Paris, Madrid and Cologne, Germany.

Artistically, when he got back to L.A. from Ibiza, Irwin merely picked up where he left off, making tepid if skillful abstract paintings with landscape overtones, selling a few here and there. He snagged his first solo show in 1957 at Felix Landau Gallery on La Cienega Boulevard, then the city’s premier showroom.

He also dropped into a rambunctious space newly opened just up the street from Landau. Ferus Gallery started out slowly, but by the time it closed in 1966, had become one of the nation’s most adventurous art spaces, showing Jay DeFeo, Craig Kauffman, Kenneth Price, Andy Warhol and many more. Irwin jumped from Landau and grew with Ferus.

In the competitive Ferus environment, he went through a series of almost methodical refinements in painting. Each body of work revealed questions he attempted to answer in the next body of work.

He started with small, thickly painted works barely 8 inches square, framed in wood as exquisitely polished as the finish on his old hot rods. The paintings were meant to be held in the hands and examined as refined objects. He hoped to give gestural abstraction a material heft that would correspond to a viewer’s physical presence.

Impractical, those gave way to “line paintings,” roughly 5-foot-square monochrome canvases with a few thin, horizontal lines, carefully spaced so not all of them could be taken in at once. In matching or contrasting hues that demanded close looking, they erased traditional distinctions between figure and ground.

Irwin worked slowly, taking two years to make 10 paintings.

Next came “dot paintings,” slightly bowed square canvases featuring thousands of tiny green and red dots. When viewed from several feet away, the dots coalesced into a halation of amorphous color. The surface appeared to dissolve into an optical cloud.

The dot paintings created an uproar when shown at the 1965 São Paulo Bienal, which coincided with the start of a conformist military dictatorship in Brazil. Two were physically attacked and destroyed.

These were followed by disks of aluminum or clear acrylic, mounted on posts to stand in front of the wall and illuminated by spotlights. The brightly lighted curve visually erased the sharp, angled edge that made any rectilinear painting into a figure standing against the wall’s ground.

Object, line, color, edge — in an 11-year span, Irwin had worked his way through abstract painting’s fundamentals. Subsequent experiments with light-and-space-bending geometric resin columns brought him out of the private studio and cloistered art gallery and into the everyday world. In 1970, when he was 42, he sold, gave away or destroyed the contents of his studio.

One place he went was to teach at the new UC Irvine campus in Orange County, where fellow faculty and students would include Kauffman, Vija Celmins, Chris Burden and Alexis Smith, all of whom went on to important careers. Over the next decade he also went to the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and the new Malinda Wyatt Gallery next door to his old studio on Market Street in Venice, where he installed spare perceptual installations that rocked viewers back on their heels.

Two years were spent developing a three-room installation commissioned by Italian collectors Giuseppe and Rosa Giovanna Panza di Biumo for their villa outside Milan. That artist-collector relationship helped to seed the subsequent gift-purchase by MOCA of the coveted Panza collection of American Abstract Expressionist and Pop art.

The 1980 Wyatt Gallery installation was among the most remarkable. After opening the skylights and painting the gallery walls and ceiling a uniform white, Irwin grabbed a sledgehammer and knocked down the building’s front wall. He replaced the impenetrable brick facade with a delicate plane of translucent white fabric. Day and night, illuminated by the passing sun or automobile headlights, the interior view from the street was transformed into a foggy, fluid volume of luminous space.

The penumbral environment sparked eager word of mouth that brought a steady stream of slack-jawed visitors during the show’s two-week run. Miraculously, given the general rough and tumble in the neighborhood, the vulnerable stretched-fabric scrim remained untouched.

This was a quintessential example of what was soon called Light and Space art. A wide variety of L.A. artists, creating similarly perceptual installations, became linked to the movement.

The earliest was Doug Wheeler, whose mysterious, perceptual light chambers are perhaps closest conceptually. Later, James Turrell would be the most fashionable, his platforms constructed to enclose views of the sky. Sculptors including Larry Bell, Peter Alexander, Helen Pashgian and DeWain Valentine made related objects of resin and glass, while installation artists Maria Nordman, Phillip K. Smith III and, in Europe, Olafur Eliasson expanded the genre into the present.

The now hugely popular 1997 Central Garden commissioned by Getty Research Institute director Kurt Forster for the new Getty Center would represent one pinnacle in Irwin’s long career. Opposed by Getty architect Richard Meier but constructed nonetheless, the expensive, elaborately detailed plan required moving an entire hilltop access road to more than double the available space.

The design’s path, meandering downhill beneath a canopy of London plane trees and crisscrossing a stream, led viewers into a sunken oval bowl teeming with a luxurious planted garden. Surreptitiously, Irwin put a strolling visitor’s back to the vast, spectacular hilltop-view out over the city and the Pacific Ocean. Now in intimate physical contact with densely planted floral beds and stands of flowering trees, a visitor looks up, facing north over an azalea maze that appears to float beneath a waterfall cascading into a manmade pond.

Meier’s imposing Getty Museum rises at the right and research library at the left. The heck with the ocean view. The site-determined cultural reasons for the garden’s very being frame the aesthetic experience.

Such works are sometimes erroneously described as site-specific art. Irwin rejected the term as giving priority to the site rather than the art. Reversing the emphasis, his 1985 book “Being and Circumstance: Notes Toward a Conditional Art” articulated his idea of art (or “being”) conditioned by the site (the physical, cultural and social “circumstance”) in which it would be experienced. Art historian Matthew Simms described Irwin’s work as “a resource for the suspension of habit and prejudice.”

Irwin made site-conditioned outdoor installations for diverse locations, including UC San Diego, the University of Washington in Seattle and the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas, founded by sculptor Donald Judd. Permanent indoor installations are at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, Indianapolis Museum of Art and the Advanced Health Sciences Pavilion at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. The last two works display fluorescent light tubes in wall-size geometric patterns, a medium he explored late in his career. He was also instrumental in the interior and landscape design of Dia Beacon, a small contemporary art museum in upstate New York that opened in 2003.

The Marfa project at a defunct military hospital, “untitled (dawn to dusk),” is among the most elaborate. A C-shaped concrete building, lined with windows that surround a courtyard planted with mesquite trees and a sculpture of irregular basalt columns, houses transparent indoor walls of black or white scrim, stretched taut from floor to ceiling.

Natural light illuminates the interior, shifting perceptions with the time of day and outside weather. Subtly changing light loosens the spatial geometry, altering the frame of reference around the eternity of landscape and sky seen out the windows. Seventeen years in the making, the final masterwork of Irwin’s career was completed in 2016. Since then, he focused on sculptural works made with florescent tubes wrapped in colored gels and installed vertically side by side in ordinary electrical fixtures — but without any wiring. Irwin called them “unlights.”

Irwin is survived by his wife, Adele; a daughter, Anna Grace; and a sister, Patricia Keenan.