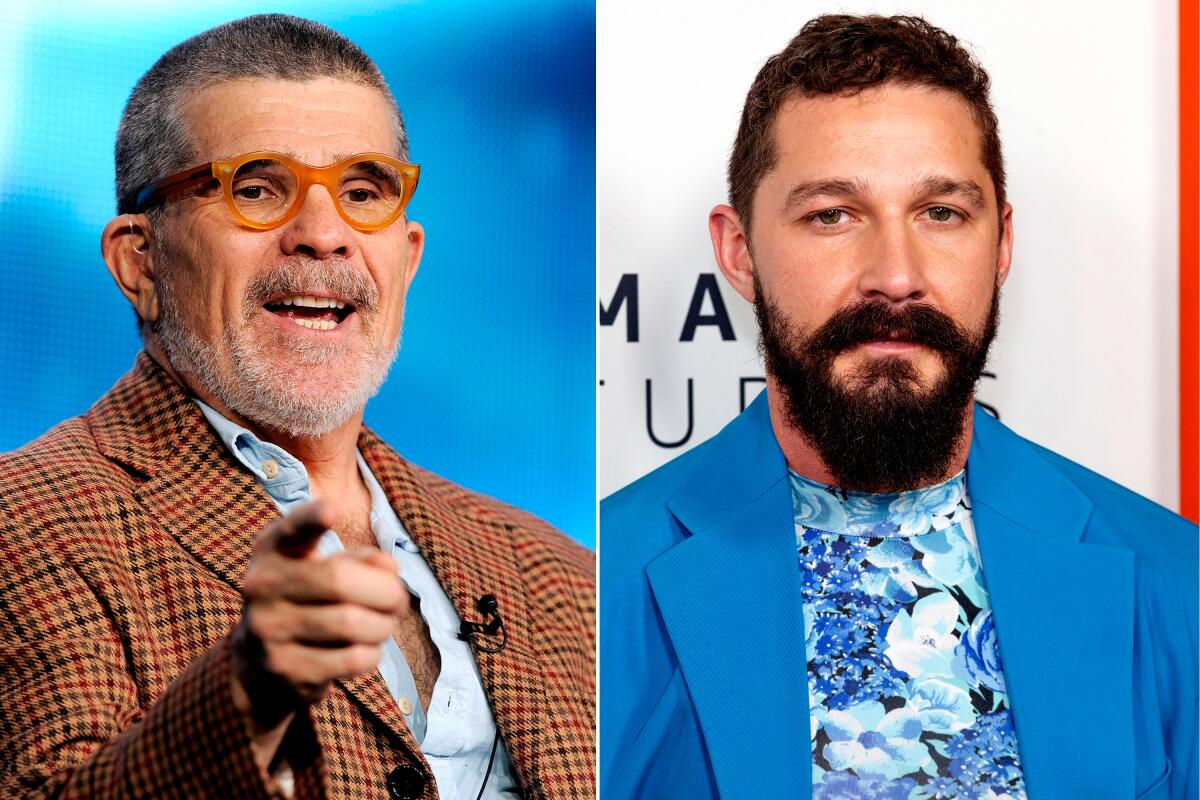

Commentary: Critics weren’t invited to David Mamet’s new play. Then the show’s star, Shia LaBeouf, sent a personal invite

David Mamet has recently unveiled a new play, “Henry Johnson,” at the Electric Lodge in Venice. Tickets have been so scarce for the production, which features Shia LaBeouf in a top-notch cast, that the September run was extended through Oct. 7.

The reason you likely haven’t heard much about this offering is that this is one of Mamet’s clandestine world premieres.

Critics were not invited, even after they politely asked. Perhaps the 75-year-old Mamet has grown tired of getting burned by unflattering reviews. He’s hardly been a critics’ darling in his late career.

But the playwright has never held my profession in high regard. He once called critics Frank Rich and John Simon the syphilis and gonorrhea of the American theater. Believe it or not, this quotable taunt was from Mamet’s more temperate days, before right-wing conspiracy theories and unhinged demagoguery set in.

In 2020, shortly before COVID-19 forced venues to close, Mamet gave “The Christopher Boy’s Communion” a trial run at the Odyssey Theatre. The production featured Rebecca Pidgeon, Emmy winner William H. Macy and stage veteran Fionnula Flanagan — an ensemble to make the Geffen Playhouse and Center Theatre Group green with envy.

David Mamet brought “The Christopher Boy’s Communion” to the Odyssey Theatre with Rebecca Pidgeon, William H. Macy, Clark Gregg and Fionnula Flanagan.

Reviewers weren’t invited, but a friend had a ticket and asked me along. Sporting professional that I am, I decided to write up my thoughts in the hope that I could help the play avoid the embarrassing end of so many of Mamet’s slapdash and tendentious efforts since “Oleanna” drew out the playwright’s worst deck-stacking impulses.

When the publicity reps of “Henry Johnson” informed me that there would not be a press opening or press tickets, I assumed that the play was still in the workshop phase and decided not to impose my critical judgments. In 2013, I wrote a piece titled “The Problem With David Mamet,” in which I diagnosed a “hardening in his work not just of ideology but of imagination.” But I have no interest in trolling a playwright of his stature.

His theatrical legacy, apart from his considerable accomplishments in film and television, is prodigious. Mamet’s gift for staccato verbal sparring transformed the way characters communicate on the American stage. “Glengarry Glen Ross” stands as one of the greatest American dramas of the second half of the 20th century.

If anyone could rest on his laurels, he can. So what if I’m not alone in thinking that he should?

In the transition from enfant terrible to elder statesman, Mamet refashioned himself as a neocon crank, sounding off like a regular contributor to the comments section of Breitbart News. In his 2022 book, “Recessional: The Death of Free Speech and the Cost of a Free Lunch,” he celebrates Donald Trump (a prototypical Mamet character), dismisses climate change, inveighs against COVID-19 safety measures and categorizes former U.S. president Barack Obama as a “race hustler.”

His views on theater are just as belligerently dogmatic. Whether the subject is the craft of playwriting or the failures of the American theater, Mamet holds forth as though he were lecturing a class of idiots.

The “Mamet Approved Quote” that was included in the press release for “Henry Johnson” had me rolling my eyes: “Constantin Stanislavski wrote that any director who does something interesting with the text does not understand the text. Most stage directors are only English teachers with a stage manager to bring them tea while they confuse the actors. God forgive them, and may God bless Ms. Ryan.”

He was referring to the director of the production, Marja-Lewis Ryan, showrunner of “The L Word: Generation Q.” It seems his opinion of directors is only slightly higher than it is of critics — and just as sophomorically unnuanced.

Suffice it to say, I was content to remain in the dark about Mamet’s latest. It has been a busy September, and I’m grateful for the rich memories I have accumulated over the years of “American Buffalo,” “Glengarry Glen Ross” and “The Cryptogram,” which I wish someone would revive soon. But then an invitation came my way from LaBeouf himself.

In an email, he wrote, “Three weeks into a successful run of ‘Henry Johnson’ and we have yet to receive a review, analysis, or any illuminating interpretation of our work, positive or negative. Outside of a few tweets, and word of mouth. I know Mamet prefers this. Personally, I find dramaturgical criticism instructive and generative. I think it’s good for the sport and I would be pleased as punch if you could join us in attending the play one of these days.”

What’s a critic to do in the face of such a courteous entreaty? I knew little about LaBeouf’s private travails, which include troubling allegations of abuse, battery and theft. I couldn’t tell you much about his film career, except that I vaguely recall the near-Afro he sported playing John McEnroe in a movie that I fitfully watched on an interminable flight.

He’s also a theater artist, but maybe one of the reasons I have to take that on faith is that two of my Times colleagues working on a feature were escorted abruptly from the chaos of rehearsals of “5711 Avalon,” an unorthodox piece he was directing for his Slauson Rec. Theater Company during a tense period in the pandemic. “Henry Johnson” represents his stage debut.

And that, patient reader, is how I came to review “Henry Johnson.”

I feared disaster but found intrigue. The opening scene may be Mamet’s strongest in years. Evan Jonigkeit, who plays Henry Johnson, is seated opposite Chris Bauer, who plays Mr. Barnes, a senior business associate. Mr. Barnes is interrogating Henry on his relationship to a friend he recommended for a job.

It turns out this buddy from college (who doesn’t appear) has served time for manslaughter, having pleaded to a lesser charge to avoid risking life in prison for a murder conviction. But the crime, as details are revealed, is shocking. This man attacked a pregnant woman he was having an affair with to induce an abortion after she refused to end the pregnancy. He brutally succeeded.

Mr. Barnes knows more than he lets on. It seems that murder might not be the only charge that was skirted. Rape is mentioned, though Mamet doesn’t carefully parcel out the exposition. The opening exchange is treated as cross-examination masquerading as comradely colloquy. What’s driving the inquiry isn’t so much the factual backstory concerning Henry’s friend as the precise nature of Henry’s relationship and the reason for his persevering loyalty.

Mr. Barnes deduces that Henry has been manipulated and illegally used — “groomed,” in effect — to do the bidding of a sociopath. Was Henry sexually enthralled to this madman? Or was he seduced by his masculine prowess and virile confidence? Henry claims that he was merely trying to do an old friend a compassionate turn.

Jonigkeit, a screen actor (“X-Men: Days of Future Past,” “Bone Tomahawk,” “Easy”) who happens to be married to Zosia Mamet, the playwright’s actor-musician daughter, gives definition to a character who is meant to be amorphous. He’s a cipher with a sympathetic yet disturbingly opaque center.

Bauer, an esteemed Mamet veteran, is superb. He keeps the dramatic pressure on through his expert delivery of a barrage of pointed questions and knowing retorts. In Mamet work, characters don’t exist prior to their dialogue but create themselves through the words they deploy with various degrees of cunning.

Plot is similarly a function of talk. “Henry Johnson” unfolds in a series of scenes, composed as duologues, all of them except the first set in a prison. The play, which runs only about 80 minutes with intermission, has lacunae, gaps that are sometimes the result of the playwright’s desire to remain ahead of his audience and sometimes the result of garbled writing and performance.

Mamet requires a director to treat the play as a score, paying exquisite attention to modulation and clarity of utterance. Actors who can link psychology to speech have an advantage over those who need to slip into a fully drawn personality before firing off a line.

The cast, which includes Dominic Hoffman in the role of Jerry, a prison guard, is uniformly good. But under Ryan’s direction, the less experienced Mamet performers seem to be acting for an invisible camera. LaBeouf is scarily good in the role of (spoiler alert) Henry’s cellmate, Gene, an alpha dog who recognizes a submissive pup as soon as he sees one and has a few other things in common with what we learned about Henry’s pathological college friend in the first scene.

The “grooming” line from the opening scene looms over the entire play. For Mamet, human relationships are all about power. Dominion is the aim, but the sneakier the conquest, the sweeter the victory. Poor Henry is overmatched in every encounter, but he’s a willing chump. What makes him a victim is also what makes him unpredictably dangerous.

To say the word “coin” in American Sign Language, you join the tip of your index finger to your thumb to create a circle, like making the “OK” sign, and then place the palm of your other hand beneath it.

Jonigkeit’s Henry instinctively covers up his complicity with a dejected sincerity. His easy-going, lovable loser demeanor is an ideal camouflage for lawlessness.

The first scene is brilliantly written and executed, thanks in large part to Bauer’s muscular stage presence. LaBeouf ratchets up the menace by playing an incarcerated man whose aggressive nature pokes out from behind a philosophical façade. While devising an escape plan involving Henry and the (unseen) woman prison counselor who has taken a shine to the newcomer, Gene spouts wisdom like a con man on a book tour. He senses his cellmate’s sexual susceptibility to domineering men and plants ideas that are all the more provocative for not being pursued.

His character’s pathology is so terrifyingly rendered that I felt frustrated at times by the way he kept falling into a whisper. More discipline with each line — even those that haven’t been perfectly honed — is needed. The final scene between Henry and Jerry moves the story rapidly to a showdown, but key parts of the plot are swallowed in Hoffman’s diction, which seems pitched to a more casually realistic medium.

But I’m grateful to have been belatedly invited to “Henry Johnson” for the simple reason that it proves that Mamet still has much to teach us about the dark side of human relations. His theatrical microscope remains one of the strongest for examining the quest to control and to conceal whenever two people are alone in the same room.