1

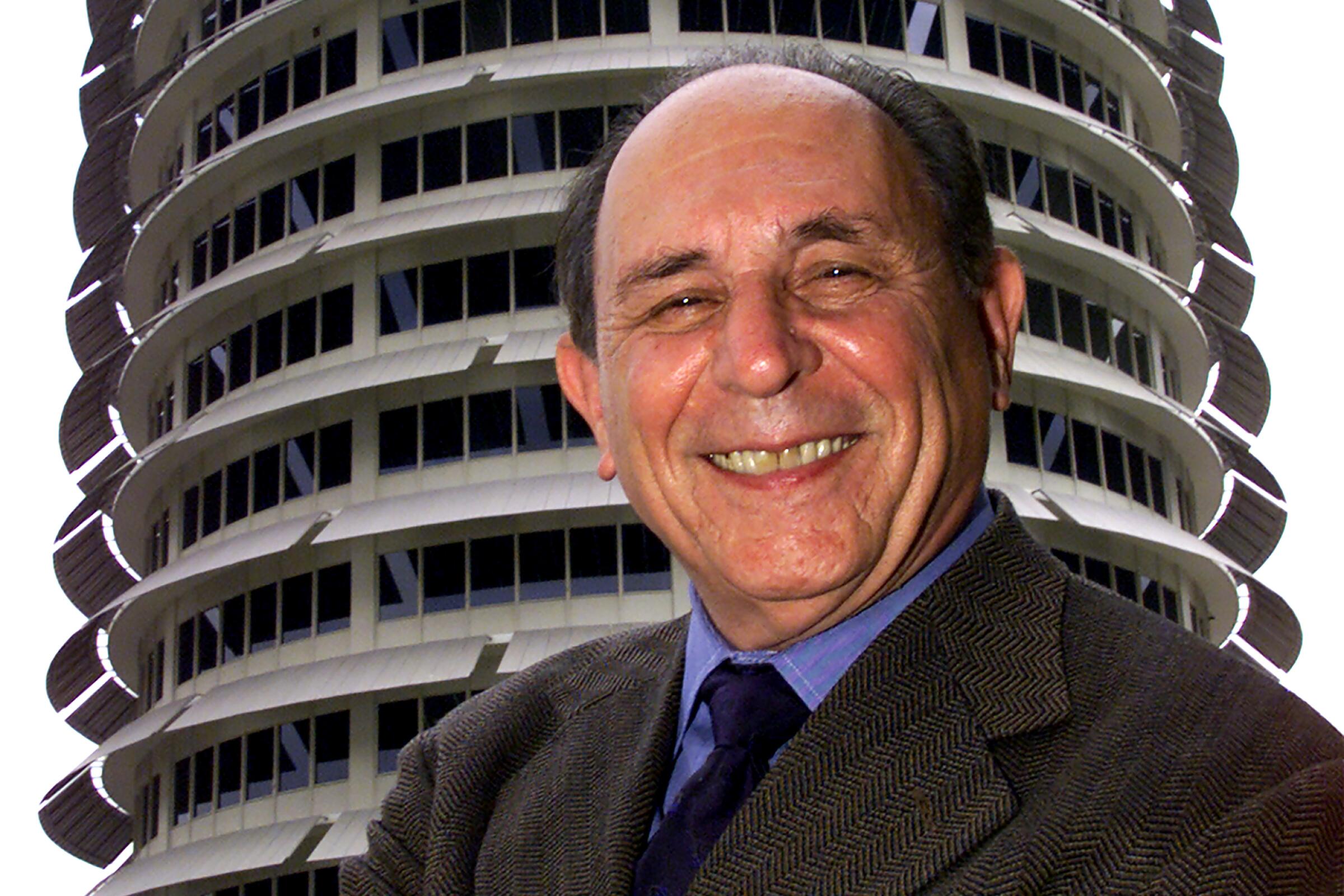

Architect Louis Naidorf had a disastrous 80th birthday cake. In 2008, Naidorf, who designed the Capitol Records building in Hollywood, was presented with a celebration cake that had been custom-baked in the shape of his iconic cylindrical building. But the pastry soon reflected the rather substantial difference between concrete and flour.

“When the cake was brought out, it gently collapsed, and everyone applauded,” Naidorf says, laughing over the phone from his home in Santa Rosa. “It was like in one of the movies where the Capitol Records building was destroyed.” Thankfully the cake for his 95th birthday, which he celebrated last month, was more structurally sound.

Designated a historic-cultural monument in 2006, the building has long been a favorite Los Angeles landmark to demolish on film — especially for filmmaker Roland Emmerich, who blew it up with an alien spaceship in “Independence Day” and slammed it with twisters in “The Day After Tomorrow.” Yet no movie can ever write the building out of a central place in popular music history. The tower is synonymous with the illustrious Capitol Records, home of Nat King Cole and Frank Sinatra, and the American record label of Pink Floyd and the Beatles, with the latter’s stars lining the Hollywood Walk of Fame right in front of the building.

Over the last several years, the building has been illuminated in support of various sociopolitical causes. In 2020, it was lighted red to support independent music venues. Last year, during their performance in Hollywood, Duran Duran lighted the Capitol Records building blue and yellow in solidarity with Ukraine. “I think that’s excellent,” Naidorf says. “Anything that vigorously engages the public on the right side of good causes transcends other issues. I’m flattered they use the Capitol Records building. It means it has enough cachet to merit being chosen to do that.”

Like the famous landmark he designed, Louis Naidorf has of late been experiencing his own brush with stardom, with postcards from autograph seekers arriving at his door. He is flattered but doesn’t take the attention too seriously.

“It’s obvious that if someone asks me for four signatures I’m part of trading baseball cards or something,” he says. “They are going to trade four Lou Naidorfs for one Joe Smith.”

Still, he’s surprised and somewhat baffled by the sudden burst of recognition after all these years. “I guess my name ended up on a list or something,” he shrugs.

An aerial drone view of the Capitol Records Building in Hollywood and the downtown Los Angeles skyline on Sept. 13, 2023.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Naidorf was just 24 years old when he designed the Capitol Records building, in 1953. It was the world’s first circular office building.

Though it was 70 years ago, he vividly recalls how he felt when he received the assignment for his first solo project. “At one level, I felt enormous anxiety that if I didn’t get a solution, very, very quickly, something terrible would happen,” he says. “On the other hand, I felt a total confidence that I could do it. So it was a crazy contradiction.”

Naidorf notes the building’s porcelain enamel sunshades with carefully spaced gaps to play with light and shadow. These cause spiral lines to appear on the building, drawing the eye into a rhythm rather than straight up and down. “You can see Capitol Records from quite a distance and you get a first impression of its basic form and character. You have a reading of it as complete,” he says. “But the building is designed so that the closer you get to the building, you discover more details.”

The Capitol Records building’s porcelain enamel sunshades create spiral lines that draw the eye into a rhythm rather than straight up and down.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

What about the long-standing myth that its round shape was designed to look like a stack of records with a rooftop antenna resembling a phonograph needle? As hard as it might be to believe, the legendary story about the building is just a coincidence — an urban legend that Naidorf has tried to debunk for decades.

In fact, when his boss, Welton Becket, tasked him with the assignment, the building was simply referred to as Project X. Shrouded in secrecy, Naidorf was given little guidance for the project other than being asked to design a 13-story building on a sloped side street in Hollywood that had to be kept as cool as possible and had smaller than usual floor space. He also didn’t know for whom he was designing it. Naidorf says it was common for clients’ identities to be kept confidential during the initial planning stages of a project.

However, Naidorf relished the creative latitude. The absence of information left him unburdened by preconceived ideas. “I knew the door was open for something special. It urged me so strongly,” he says earnestly. “I felt, and I think all architects feel this way … there’s a drive to translate the mundane bare requirements that clients come in with into something that has some poetic qualities about it.”

Naidorf then had an epiphany: The project’s requirements were “eerily resonant” with a series of circular buildings he had designed for his master’s thesis in college. “The round shape is a very efficient enclosure of space,” he says. “You get more bang for your buck.”

Not everyone agreed with his approach. Naidorf says that Capitol Records co-founder and President Glenn Wallichs became irate when Naidorf presented him with a model and drawings of a round building, and “violently rejected” the design. “He thought it was a cheap stunt designed by a young guy to make the building look like a stack of records,” Naidorf says, laughing.

Wallichs insisted that Naidorf replace the round design with plans for a rectangular building. But when both rectangular and circular designs were presented to the insurance company financing the land, Naidorf says that Wallichs was urged to proceed with the round design.

Soon after, when talk of the building housing a radio station (that never came to fruition) was raised, Naidorf fretted when he was asked to design an antenna. He was worried that it would look like a phonograph needle and cement the idea that the building was designed to look like a stack of records.

Owing to his nagging concern, Naidorf positioned the rooftop spire asymmetrically, poised to appear as if it touches the roof delicately, like “a ballerina en pointe.” He calls it the building’s “grace note.” Still, the stack-of-vinyl myth persists. Laughing, Naidorf says, “It’s the most enduring myth of all.”

Despite his good humor, it leaves him conflicted. “The building was not designed as a cartoon or a giggle. To have it trivialized with the stack-of-records myth is annoying and dismaying,” he says. “There’s not a thing on the building that doesn’t have a solid purpose to it.”

Naidorf’s ingenuity has been especially impressive to Los Angeles-based architect Lorcan O’Herlihy, who says he has “often responded strongly to the fact and admired that here was this interesting architect [Naidorf] who was combining science and art, or artistry and technology. Welton Becket [& Associates], very much to their credit, were at a period where modernism was at its heyday and they had to come up with ideas that were new and fresh and they did it, and Lou was certainly instrumental in that. His work is extraordinary.”

Architect Louis Naidorf calls the spire on the Capitol Records building’s roof its “grace note.”

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Naidorf was born in Los Angeles in 1928. His father owned a shop where he made and sold women’s clothing, with Naidorf’s mother lining the garments. Owing to his father’s lack of accounting skills and business acumen, however, the business often collapsed, forcing his parents to work at a garment factory until debts could be paid off to reopen the store.

Throughout his childhood, Naidorf’s family struggled financially as they moved around, living mostly in Silver Lake and Los Feliz. With only enough money to rent studio apartments, Naidorf’s parents slept on a Murphy bed while Naidorf spent his nights on a mattress on the floor.

As a little boy, Naidorf felt drawn to buildings. When his third-grade teacher decorated the classroom with a Hawaiian vacation theme, his fascination morphed into a calling. “I asked my teacher who made the drawings and she said, ‘Naval architects.’ And then I asked her who draws the plans for houses and she said, ‘Architects.’ She told me to ask my mother to show me the floor plans that were published in the real estate section of the Sunday edition of the newspaper.

“When I saw them, I was a goner,” he swoons. “I now knew what I wanted to do. I wanted to be an architect.”

Naidorf remembers, at age 8, designing a three-bedroom house, using a card table as a makeshift drafting table. Soon after, he began designing small towns. “It wasn’t anything brilliant, but I was learning to draw, learning to scale and learning to think in spatial terms,” he says. When he was 12 years old, Naidorf got a part-time job at a bookstore, where he spent his first two paychecks on architecture books, absorbing them until they were threadbare.

Beyond literature, Naidorf amassed a growing collection of architectural materials (T-square, rectangles, instruments for ink drawings), thanks to his bar mitzvah presents, and decided he was ready to get to work. Sanford Kent, a young architect who had just graduated from USC, hired a tenacious 13-year-old Naidorf, paying him out of his own pocket.

Naidorf says tackling the abstract problems Kent gave him at once stimulated his mind and were instrumental in forming his long-standing ethos. “It got me thinking about architecture in terms of its effect on human emotions. The key issue is, ‘How do people respond to your work, whether from a distance or by living it?’” he says.

He continued to soak up whatever he could about architecture, gearing his junior and high school classes toward studying architecture in university. He attended UC Berkeley instead of the privately funded USC, not only to leave home and expand his horizons but also because of its affordability.

Even still, Naidorf couldn’t afford all of the program’s required materials. He borrowed airbrushes from his fellow students, who would also give him their pencil stubs instead of tossing them out. Naidorf submitted his assignments on pebble board, which was not only cheaper than illustration board but allowed him to draw on one side, flip it over and draw on the other.

In 1950, Naidorf graduated at the top of his class and got his master of architecture degree a year early. He skipped his graduation ceremony because he had a job interview the next day at Welton Becket & Associates, where he was promptly hired. Among his earliest design assignments: a tray slide for a hospital cafeteria, a clothes closet and a “Please Wait to Be Seated” sign for a restaurant.

Three years into his employment, he began working on the Capitol Records building. Naidorf says he would design it the exact same way if he were given the assignment today.

Andrew Slater, former Capitol Records president and chief executive, says, “When you go to work every day in that building it’s like you’re going into a piece of art.”

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Andrew Slater, former Capitol Records president and chief executive (2001-07), attests to the building’s distinctive charm. “When you go to work every day in that building it’s like you’re going into a piece of art, and it informs your attitude ... to do something with that mindset, which is great,” he says. “Even though working in the music industry is, in a sense, an industrial endeavor, you never felt like you were doing anything industrial when you walked into that building.”

Still, Naidorf fears being perceived as a “Johnny One Note,” as he puts it. Noting the plaque bearing his name outside the building’s main entrance, he expresses gratitude but wariness “that this one modest project has to carry my whole reputation on it.”

It’s a fair point, given the magnitude of Naidorf’s notable oeuvre. It’s earned him 17 regional honor and merit awards and AIA California’s Lifetime Achievement Award (2009). His work also has been featured at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

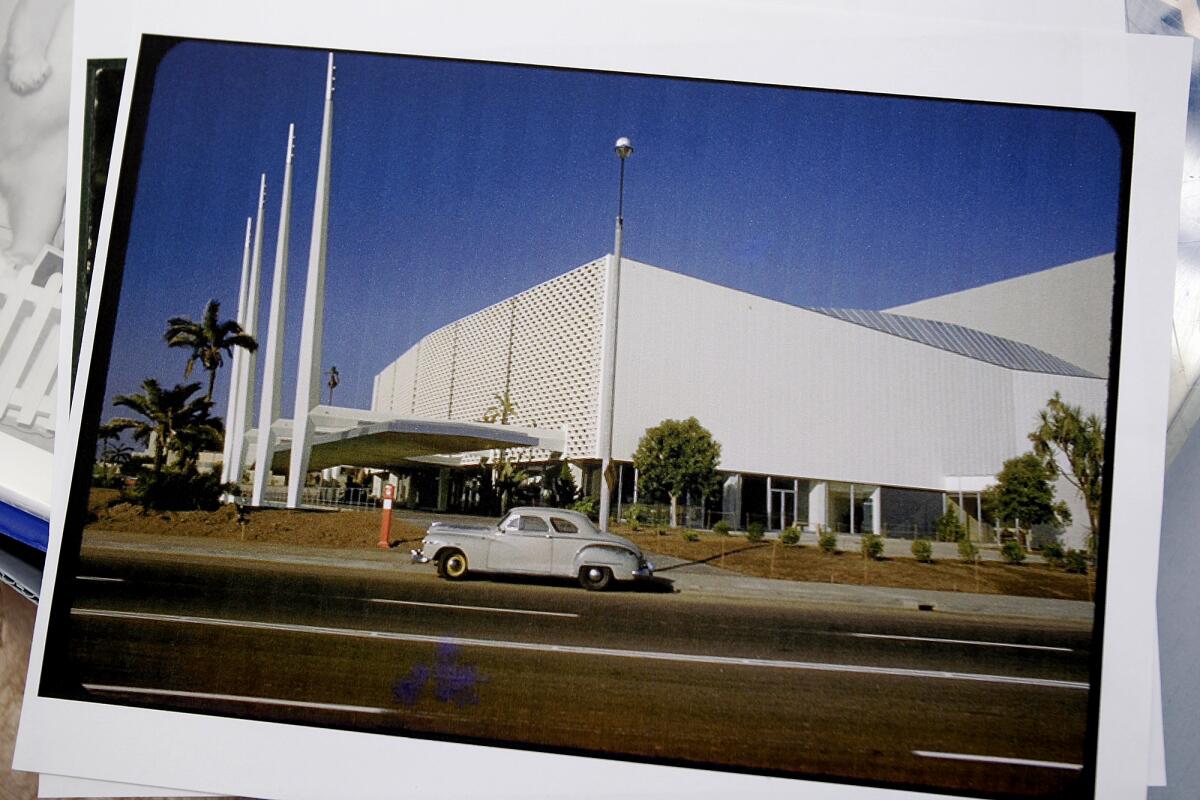

“I know Capitol Records is always the first one people talk about and it’s a splendid, iconic building that fuses artistry and functionalism, but he’s also produced other projects over the years,” says fellow architect O’Herlihy. “The Santa Monica Civic Auditorium is brilliant.”

An early photograph of the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, designed by Louis Naidorf.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

An early photograph taken inside the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

Naidorf designed the 3,000-seat capacity Santa Monica Civic Auditorium on the heels of the Capitol Records building, in the late 1950s. Essentially two buildings in one, it was a challenge to design a locale that functioned at once as a performance space with a sloped floor and an exhibit hall with a flat floor for sports events, banquets and trade shows.

He transformed the floor from flat to tilted using a hydraulic system that was hailed for its innovation. “I don’t think you’ll find any place that has a symphony on a Friday night and a gem show, or some kind of hobby show, on Saturday,” he says.

Formerly home to the Santa Monica Symphony Orchestra but currently sitting vacant, the Civic Auditorium opened its doors to the public in 1958. From 1961 to 1968, it hosted the Academy Awards. It also was the site of live recordings including George Carlin’s comedy record “Class Clown” and the Eagles’ “Eagles Live,” a double LP recorded during their three-night run at the venue. It also hosted “The T.A.M.I. Show” in 1964.

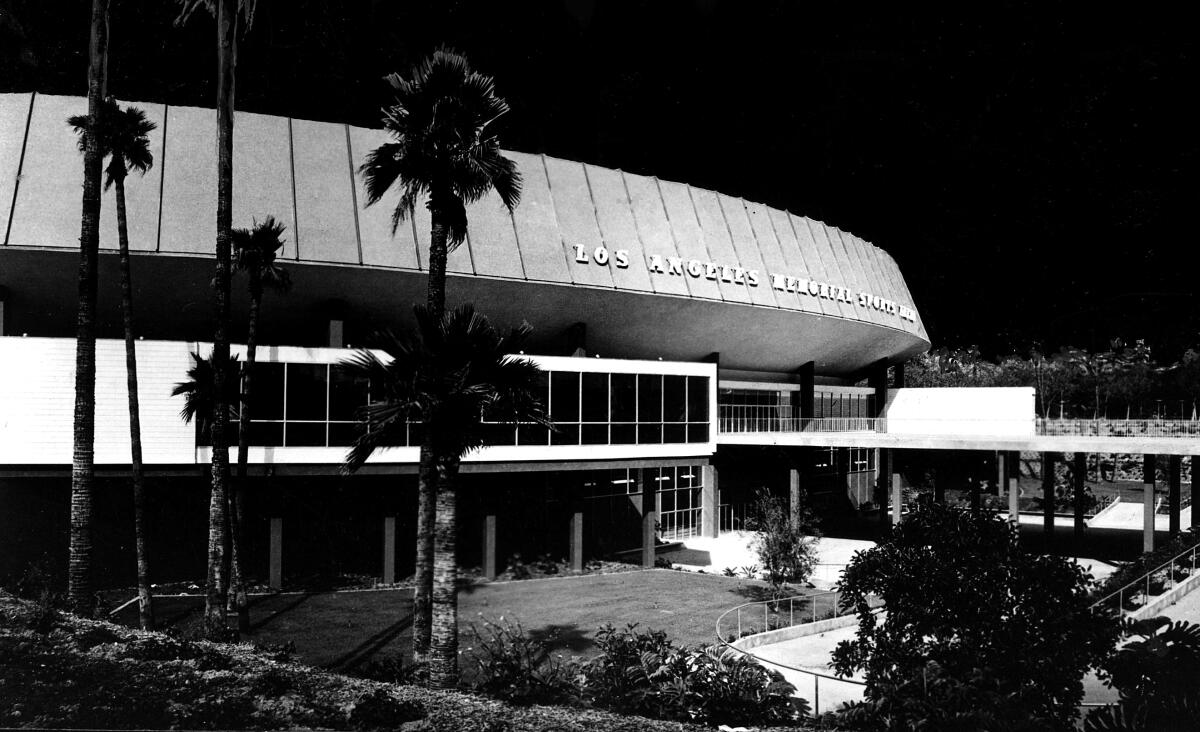

In the meantime, while the Civic was still under construction, Naidorf designed the 15,000-seat capacity Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena, the biggest arena in Los Angeles when it opened in 1959. (The arena was demolished in 2016 to make way for the Banc of California Stadium, now called BMO Stadium.)

The Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena, another Naidorf design, on May 26, 1960.

(Los Angeles Times)

Naidorf says the Sports Arena, home to various Los Angeles sports teams including the NBA’s Lakers (1960-67) and Clippers (1984-1999) and the NHL’s Kings (1967-68), was built to attract sports teams to Los Angeles, but uncertainty about whether they’d catch on meant the facility had to be viable for other purposes.

In 1960, a year after it opened its doors, the Sports Arena hosted the first Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, where John F. Kennedy became the presidential nominee. Muhammad Ali (then known as Cassius Clay) won a boxing match there in 1962. It also hosted rallies by Martin Luther King Jr. and the Dalai Lama, and saw concerts by legendary rock acts including the Grateful Dead.

Bruce Springsteen played the venue’s final concerts before the building was demolished, a three-night stint during which he dedicated his song “Wrecking Ball” to the building lovingly nicknamed “The Dump That Still Jumps.” “Well, it was pretty dumpy by the end,” Naidorf says, laughing. “Not all architecture is permanent,” he continues. “I’d rather it was demolished and some useful purpose made of the site than having it sit there old, shabby and neglected as it was.”

Naidorf’s credits also include the Beverly Hilton Hotel, the Beverly Center and the Reagan State Office Building downtown. Outside of Los Angeles, Naidorf helmed the restoration of the California State Capitol Building in Sacramento, a six-year undertaking and then the largest-ever restoration undertaken in the U.S., and he designed President Gerald Ford’s house in Rancho Mirage.

The tallest building in Arizona, the Valley National Bank building (now Chase Tower) in Phoenix, also was designed by Naidorf, as well as the Hyatt Regency Dallas and adjacent Reunion Tower, the most recognizable landmark of the city’s skyline.

The California State Capitol Building in Sacramento in 2014.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

He details these and his other high-profile projects in his 2018 book “More Humane: An Architectural Memoir”, filled with photos, backstories and personal anecdotes. Flipping through its pages, one learns that Naidorf not only took risks designing his projects but even risked his job on occasion.

He writes in his memoir that in 1958, when he was designing the Humble Oil (now Exxon) headquarters in Houston, he refused to design separate locker rooms and drinking fountains for Black and white people, as the company asked him to. When he went home on that Friday night, he describes not knowing if he’d have a job the following Monday. Not only did Naidorf not lose his job, he says, but the company ceased segregating its locker rooms and drinking fountains after that.

“I realized architects have access to some of the most powerful people in the world and it is our job to bring up issues that represent social issues rather than just architectural design,” he says. “The only thing for evil to triumph is for good people to remain silent. Architects should not remain silent.”

Naidorf also understood that sometimes he was designing projects where people don’t want to be, like the Naval Medical Center in San Diego, which opened in 1988. “I felt that there were two emotions we had to contend with,” he says. “One was to lay the sense that this would be welcoming and have a more personal quality. But if you go to a hospital you want a quite contradictory thing. You want to have a sense that it’s state-of-the-art, that whatever powerful forces can cure you, they’re there.”

Instead of one medical building, which he felt would seem ominous, he designed several structures and a series of outdoor walkways to make the facility feel warm and comforting. The treatment and diagnostic part of the facility was bold, with an abundance of steel and glass. Walkways were lined with floor-to-ceiling glass to allow patients to see the outdoor courtyard, grass, trees, sky and distant views of a golf course “based on the primitive feeling you have in the hospital, which is to get out of the damn place,” he says.

When he was out shopping a few months ago, Naidorf met a woman who mentioned that she had been in the Navy, forcing her to move around a lot when her son was battling childhood leukemia. Without knowing she was talking to the Naval Medical Center’s designer himself, she told Naidorf that it was the only hospital that didn’t scare her ill 6-year-old son, who has since made a full recovery.

“What kind of an architect…,” Naidorf says, overcome with emotion and his voice breaking, “do you have to be not to hold that as better than any design award?”

Capitol Records can stand on its own

Though Naidorf had risen through Welton Becket & Associates’ ranks to become vice president, director of research and director of design, he grew increasingly unhappy after the firm’s merger with Ellerbe Associates (it was renamed Ellerbe Becket). He moved into academia full-time in 1990, spending just one day a week at the firm.

Naidorf became dean of the School of Architecture and Design at Woodbury University, earning numerous distinctions, including teacher, faculty member and administrator of the year. He was also a guest professor at UCLA, USC, Cal Poly Pomona and SCI-Arc. At his retirement ceremony in 2000, he was awarded an honorary doctorate, marking not only the end of his academic career but also his time in Los Angeles.

The Alumni Quad at Woodbury University in Burbank in 2018.

(Raul Roa / Los Angeles Times)

Charmed by the beauty of Northern California, Naidorf moved up the coast to Santa Rosa. For the next 15 years, he continued working with Woodbury University as campus architect, designing and remodeling some of its buildings, and was invited to be a board member.

When he parted ways with Woodbury at 87 years old, it was not with the goal of taking it easy. Naidorf had other pursuits in mind, including his work with City Vision Santa Rosa revitalizing the city’s downtown area.

He also helped his close friend, Mike Harkins (who edited Naidorf’s memoir), design his new house free of charge after the 2017 Tubbs Fire burned Harkins’ home to the ground and he and his wife lost 99% of their belongings.

“Lou offered without solicitation: ‘I’d like to design your house,’” Harkins says. “To me or anyone else who knows him, it was a heartfelt offer that of course he would make, and yet so much more. One analogy might be if Eric Clapton said, ‘I’d like to play at your wedding.’ The knowledge and sensibility that comes along with a Naidorf design offering is huge, just like his heart.”

Most recently, Naidorf has been experimenting with plans for a project to help people who are unhoused.

Naidorf has made the most of his architecture license over the last 71 years. His voice fills with pride when he reveals that he holds the earliest issued active architecture license in the state of California, obtained in 1952.

“It’s something I wanted to be since I was a little kid. My architecture license was so hard to come by. I don’t want to give it up,” he says with palpable emotion. “I don’t want to be retired. I want to be an architect until I fall over. I plan to be buried as a licensed architect.”

Louis Naidorf, pictured when he was dean of the School of Architecture at Woodbury University in Burbank, in his office.

(Ann Johansson / For The Times)

Of recently turning 95, he jokes that he feels like a bad vaudeville performer who soon will be pulled offstage by a hook. But Naidorf remains in remarkably good health after surviving both prostate and esophageal cancer in his 80s.

To keep his brain sharp, he does exercises including counting backward from 100 by sevens and taking IQ tests online.

As a nonagenarian, he says there is no key to living a long life. He suggests, though, that it helps to try to use it well. “It’s not how big the steak is but how tasty it is,” he says. “I think you have to seek a calling, listen for it and search for it. Find something in your life that is really yours. … Get engaged with something that’s going to scare you, something where the problems are hard. And take risks. There is no failure.”

He also notes the importance of adaptability. “I have had four marriages. I’d better be resilient,” he quips. Twice divorced and twice widowed, Naidorf has a daughter from his first marriage, four stepchildren (who call him “Dad”) from his fourth marriage, 11 grandchildren and six great-grandchildren. An intensely private man, he’s reticent to speak publicly about his relationships and family, preferring to focus on his work.

“I remain so fascinated with architecture,” he says. “I cannot even walk past a store where somebody is putting in an electrical outlet without stopping to look in and watch it.”

The chatty Naidorf turns summarily succinct, saying, “I certainly have had a good run.”