Review: P-22 is remembered with fanfare at the Hollywood Bowl, in one of his favorite neighborhoods

A new Los Angeles legend we might all be able to agree on is P-22. The mountain lion, who made the area around the Hollywood sign his home and roamed Griffith Park and the Hollywood Hills, may have snacked on the occasional pet or resident at the nearby L.A. Zoo. But he remained beloved and a star of television and this newspaper, which featured him on the front page 11 years ago, a few months after he was first discovered. His death this past December became international news.

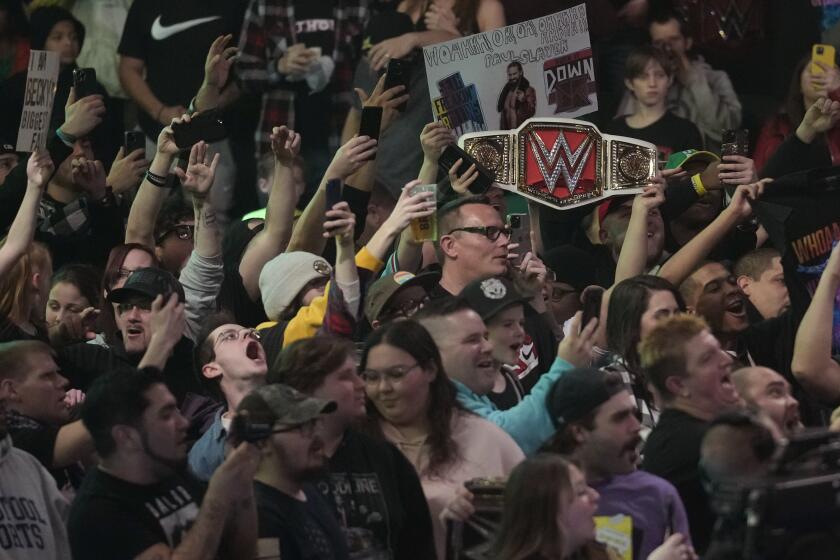

Did P-22 manage to cross Cahuenga Boulevard and the 101 Freeway to cruise the Hollywood Bowl? There is a good chance he did. And what a feast he might have found Tuesday night, when the Los Angeles Philharmonic paid the “Hollywood Cat” tribute at its last symphonic Bowl concert of the summer. The amphitheater looked about full, which meant had P-22 been on site he would have had the sight of a banquet beyond the imagination of even the hungriest lion king — the pick of some 18,000 delectable human main courses, to say nothing of the picnics they may have brought.

But it was just the opposite with the premiere of Adam Schoenberg’s fanfare, “Cool Cat,” commissioned by the orchestra. The composer, who balances a career among writing for film, television and the concert hall, credits the prowling puma for having saved his life. He composed “Cool Cat” while undergoing a health crisis of acute ulcerative colitis, Schoenberg noted in an interview for Occidental College, where he teaches. He said that writing the score “gave my body, brain and heart an extra boost in order to keep on going” while rapidly declining before emergency surgery.

The very idea of “Cool Cat” may bring to mind another fabulous Hollywood cool cat, the Pink Panther. But rather than Henry Mancini’s jazzily smooth saxophones, Schoenberg’s cat doesn’t slyly pad. His steps have percussive presence, the tympani and an edgy theme to make you eagerly await this intractable Hollywood luminary to pounce.

As a wistfully ebullient orchestral curtain-raiser, and one over in a flash, “Cool Cat” is well equipped to have a life of its own in various concert settings. Nor did the Bowl treat the premiere as a site-specific pièce d’occasion. Rather than take advantage of the venue’s large video screens to show scenes of P-22, it zoomed in, as usual, on the orchestra players and conductor Karen Kamensek, who was making her L.A. Phil debut and did so with verve and panache.

But afterward, when a shot of P-22 was finally projected, happy cheers and applause suddenly changed the sonic character to something more muted. It felt as though the crowd collectively recognized that it is his land we appropriate for our concerts and our roads, where P-22, hit by a car, received his fatal wound.

One way Schoenberg made this endearing cat cool was through, at times, rhythmically treading to a minimalist Philip Glass-inspired soundtrack. Kamensek is best known for championing Glass — she conducts on the Metropolitan Opera video of “Akhnaten,” which won a Grammy. At the Bowl, she followed “Cool Cat” with Glass’ First Violin Concerto. But to say that 1987 premiere of the concerto, Glass’ first major orchestral score, got a cool reception from the audience at Carnegie Hall — and a belittling one from the press — is an understatement. It was one of the chilliest receptions of an important new work I’ve ever experienced.

The mountain lion known as P-22 has become something of a celebrity in Los Angeles. After killing a chihuahua and acting erratically, he was found in a Los Feliz backyard and taken for evaluation.

A chief complaint back then focused on the coldness of the score, with its focused repetitions and chiseled orchestration. That was emphasized by an exacting violinist, Paul Zukofsky, and conductor, Dennis Russell Davies. Zukofsky, in particular, was a brilliant virtuoso who loathed the sentimental use of vibrato and portamenti, the sliding along a violin string of one note to another.

The concerto has become a popular modern classic, and become the property of a wide range of violinists. When L.A. Phil concertmaster Martin Chalifour played the first Bowl performance of the concerto in 2008, he was true to Zukofsky’s and Glass’ elegance. Violinist Anne Akiko Meyers, however, had very different ideas about the concerto on Tuesday.

Treating the solo part as something in a Romantic-era concerto of yore, she was all sentiment all the time, including lots of emotive vibrato and startling portamento leaps in the slow movements. Kamensek maintained a reasonable pulse but happily joined in for making big moments as big as they could get.

It would be easy to be taken aback. Yet this is what performers have done throughout the centuries, making the music theirs. Bach and Mozart were not around to protest. Glass is, and so are some of us. Even so, Glass has always had an open mind, and he was on hand to take a bow. Nevertheless, an illuminating 2017 recording of the concerto on Glass’ own label, Orange Mountain Music, with violinist Renaud Capuçon and Davies conducting, tells another, far more convincing story.

Holst’s “The Planets” was the final spectacle on Tuesday night, and there was nothing cool about it. Not unlike Meyers’ way with Glass, Kamensek put a heavy emphasis on just about every detail. The thumping 5/4 rhythm in the opening section, “Mars, the Bringer of War,” emulated the thudding beat of soldiers and weaponry in relentless attack. Holst’s musical telescope is, of course, meant for astrology, not astronomy, and whether buoyant Mercury, seductively peaceful Venus, jolly Victorian Jupiter, cranky old Saturn or magician Uranus, each was sketched with show-offy, neon-bright colors and climaxes of extreme power.

The amplification, moreover, was loud and surround-sound cinematic. Bass notes on the electric organ made the ground under our feet seem to vibrate.

But something interesting happened at the end. Holst leaves the listener in the far removes of outer space, with Neptune being a study in musical mysticism, highlighted by a hidden hymning women’s chorus, as if heard from a mysterious distance. Here, though, the members of the Pacific Chorale were so boldly amplified that they became a disconcerting but oddly affecting presence. It was as though the spirit of P-22 came back for a final appearance.