As Roe vs. Wade teeters, Barbara Kruger’s ‘Your body is a battleground’ takes on urgency

- Share via

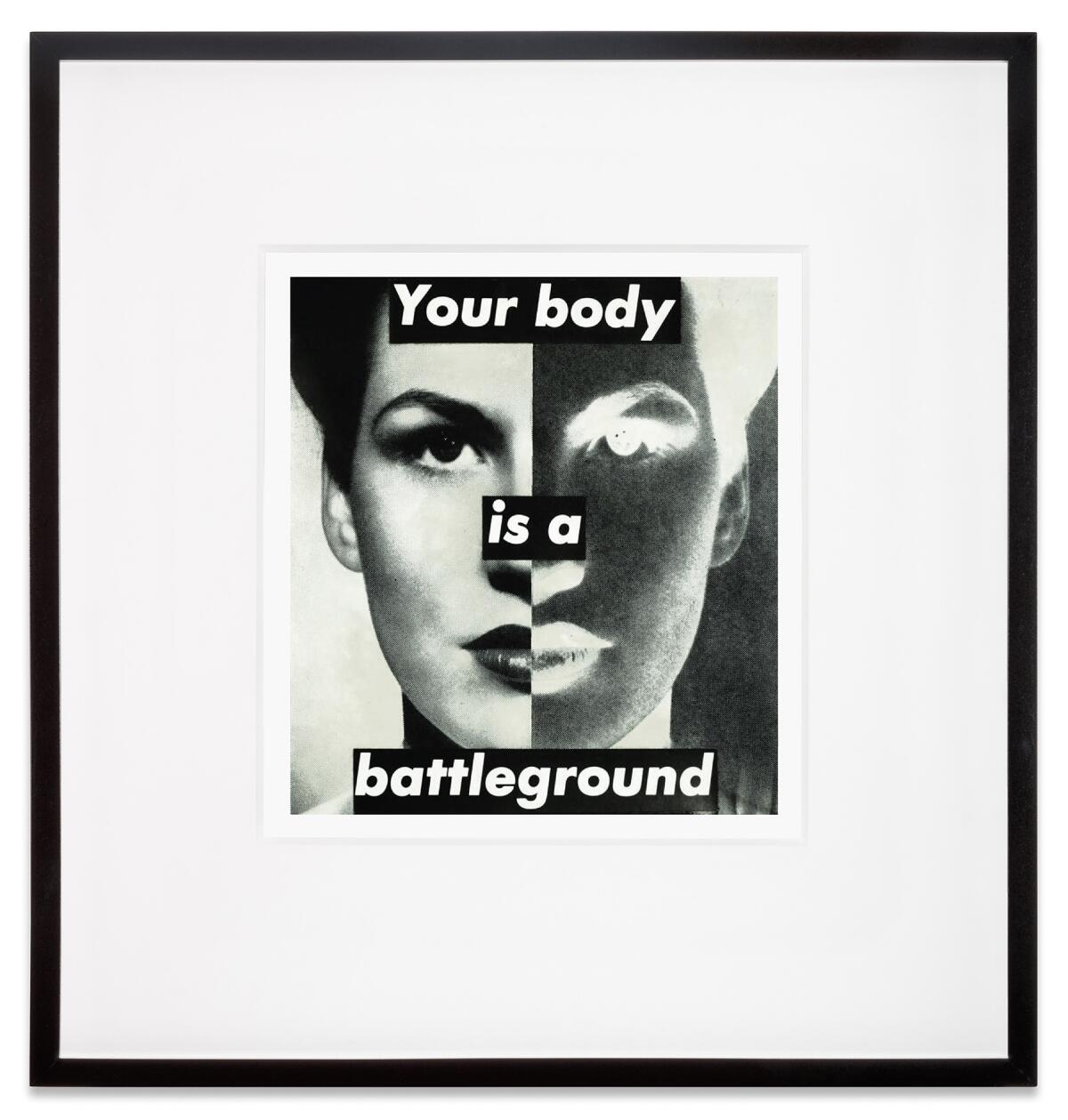

A woman’s head is bisected by a line that splits her face into positive and negative halves. Over the image, a commanding text, stated in the second person, reads: “Your body is a battleground.”

Artist Barbara Kruger’s famous collage — originally produced as a poster for the March for Women’s Lives in Washington in 1989, in support of abortion rights — was the first image my mind reached for when I read the explosive report in Politico that the Supreme Court is ready to strike down Roe vs. Wade, according to a leaked draft of the court’s majority opinion.

“The Future of Abortion” is a series of stories about the state of abortion is it is challenged in America.

I wasn’t the only one.

“Untitled (Your body is a battleground),” as the piece is officially called, began immediately popping up on artist accounts as news of Roe’s likely demise ricocheted among social media channels. This includes renderings of the original black-and-white paste-up Kruger made of the graphic (at the top of this post), as well as the silk-screen version trimmed in a screaming red that is now in the collection of the Broad museum.

“I’m so enraged right now,” wrote L.A.-based artist Cassils in an Instagram post that featured the image. “It’s going to criminalize routine women’s health care.” Sacha Baumann, who publishes the L.A. arts broadsheet Full Blede, posted Kruger’s image with an accompanying expletive. New York artist Deborah Kass added the caption: “1989. Fast forward to today.”

Also appearing on social media: lots of images of hangers.

Artist Barbara Kruger discusses her LACMA retrospective and how her explorations of mass media continue with work that responds to social media.

All these years out, Kruger’s image — a Solomonic view of a woman’s face, whose halves, in their contrasting tones, seem as if they are being pulled apart — continues to pack a punch.

The graphic remains relevant artistically. It is the modern, feminist, second-person counterpoint to Uncle Sam insisting, “I Want You for U.S. Army.”

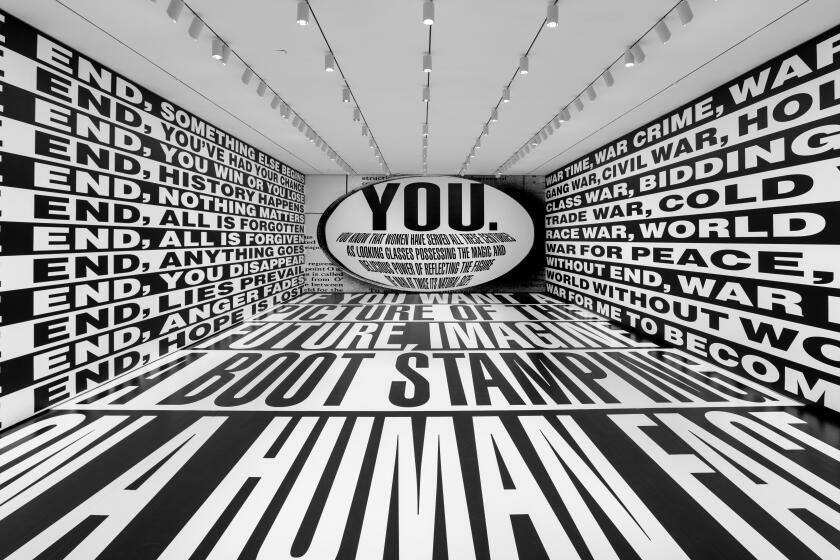

In fact, versions of Kruger’s “Untitled (Your body is a battleground)” are currently on view in the artist’s comprehensive career survey at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, titled “Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You” (with the first “you” and “me” crossed out), and in a related show at Sprüth Magers gallery, across the street from the museum.

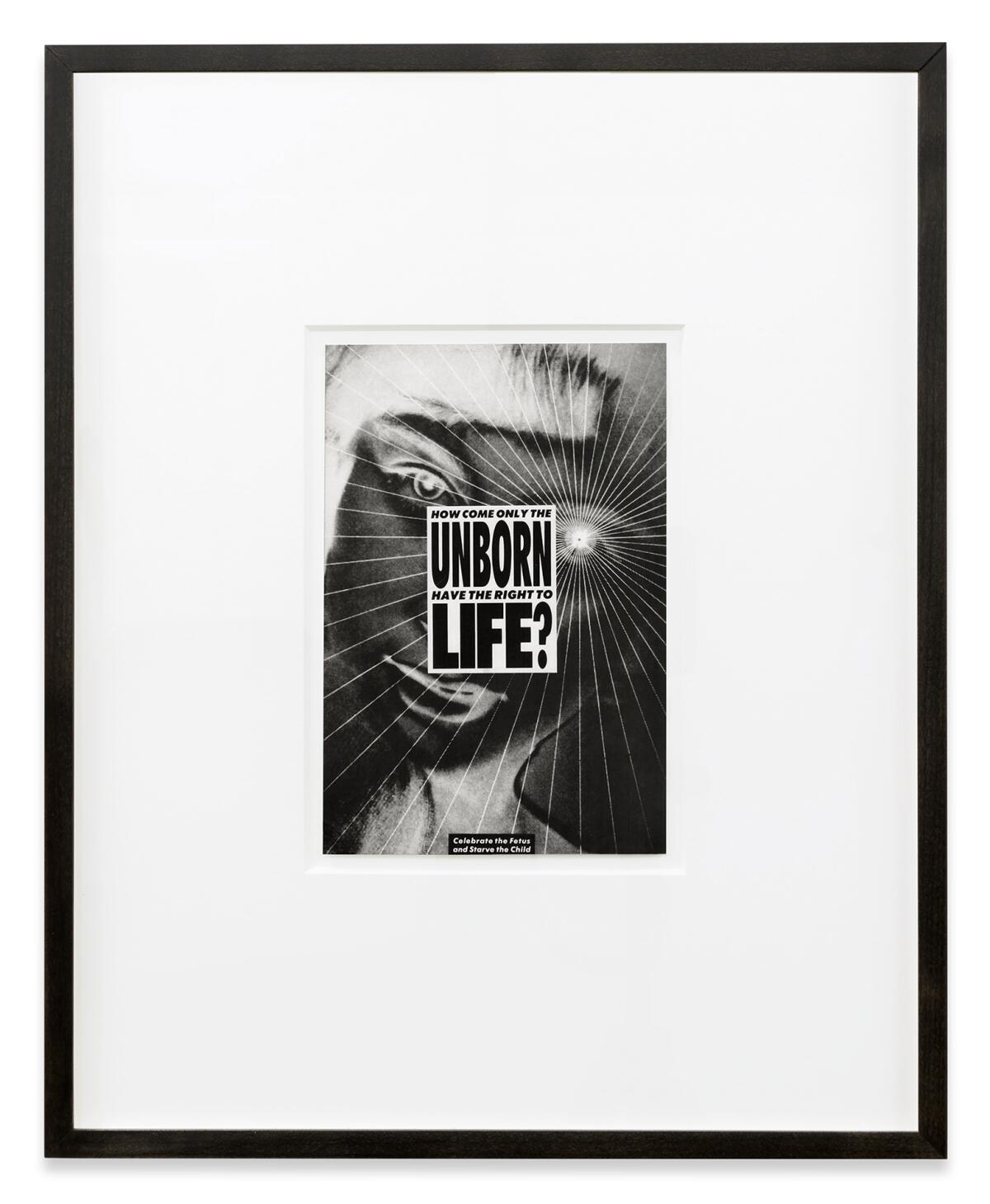

That latter exhibition also has another important abortion rights graphic designed by Kruger. Created in 1986, it shows a negative image of a woman’s face on which is superimposed a block of all-caps text that reads: “HOW COME ONLY THE UNBORN HAVE THE RIGHT TO LIFE?”

I saw that image pop up on social media too — shared by, among others, arts writer Jori Finkel.

“Untitled (Your body is a battleground)” also remains relevant politically: regularly resurfacing as an impactful rallying cry when the autonomy women hold over their bodies is called into question — hence its rapid materialization on social media on Monday night.

Now we find ourselves in a moment in which a majority of Americans support the right to abortion — yet a very vocal minority seeks to deny it. (A Washington Post-ABC News poll conducted last week shows that 54% of Americans favor upholding the law, versus 28% who would like to see it overturned — a margin of roughly 2-to-1.) Yet women’s bodies, and all the bodies that have the power to give birth, are about to become casualties to a political movement rooted not in an interest in preserving life, but in preserving segregation.

As curator Robyn Farrell of the Art Institute of Chicago writes in the catalog that accompanies Kruger’s show, it’s no accident that Kruger used the second person in her famous graphic: “By using the pronoun your, the artist implicates the viewer, regardless of gender, in the objectification of this anonymous person.”

This isn’t some abstract concept. It is us. It is personal.

Last month, I interviewed Kruger on the occasion of her LACMA exhibition. As I noted at the time, her work, over the decades, has engaged the very issues we continue to reckon with today: sex, power, race, mass media and a woman’s right to govern her reproductive organs as she sees fit.

“It would be kind of good,” she told me at the time, “if my work became archaic.”

Unfortunately, it’s now more relevant than ever. I expect that the next time I see Kruger’s image, it will be poster-sized — in the streets.