Love of a Black planet: Artist April Bey’s Atlantica soars beyond Wakanda

If you have been plotting your escape from Earth but don’t yet have a destination in mind, I’d suggest setting a course for the planet Atlantica.

On your journey, you will travel through a lush, plant-filled portal in which time will be slowed and the senses enfolded in colored light and the sounds of Super Mama Djombo, the 1970s-era roots band from Guinea-Bissau. Your ship will eventually glide into Atlantica’s Gilda region, where you’ll be introduced to the planet’s remarkable industries (such as recycling remnants of colonialism into high fashion) and its most important historical monuments (don’t miss the one that pays homage to Atlantica’s famed chicken war). You will also catch glimpses of wild landscapes and learn about local deities. Atlantica is a place where Blackness, queerness and joy are honored and elevated.

It is also a place you can visit in the form of an installation at the California African American Museum that has emerged from the fertile mind of artist April Bey.

“Atlantica, the Gilda Region,” Bey’s first solo museum show in Los Angeles, is an exuberant, sense-tingling journey through an imagined planet where Black people flourish and thrive and arrange for telepathic task management. “In Atlantica, we can solve everything,” says Bey, sitting in her bright and tidy downtown Los Angeles studio. “In Atlantica, you can duplicate your legs. If you need four legs to get somewhere faster, you can do that.”

Bey should know. She is Atlantica’s most important emissary.

That requires an explanation. And for that, I’ll need to go back.

The story starts when Bey was about 5. The daughter of an African American father and white mother from the Midwest, the artist was born in the United States but spent her formative years in the Bahamas (where she was raised in part by a Bahamian stepfather after her mom remarried).

Atlantica was an idea that emerged as family story and defense mechanism. Bey was a young girl, still living in the U.S., and enduring the taunting of classmates who made fun of her coily hair. “People were like, you are adopted because you don’t look like your mom,” she recalls.

She eventually worked up the courage to ask her father about the hostility. He responded with the following tale: “He said the reason people hate you is because we are aliens from another planet.”

Bey became enchanted by the possibility of being an observer that had been sent to Earth from another world.

“Atlantica was the name I gave it,” she says. “Atlantica is the underwater world of ‘The Little Mermaid.’ I was always obsessed with the character of Ursula because I felt like she was a hardcore feminist. Most of her dialogue is about how she used to have autonomy and she no longer does. And I grew up on the ocean, and [the Atlantic] is pretty much the only ocean I’ll get into because of the clarity.”

In her work, Atlantica became a place for which Bey has invented a history, a landscape and a people — all of which bear the imprint of her interests and experiences.

The planet’s emissaries are based on friends and figures she admires — like Marsha P. Johnson, the trans activist who resisted the brutality of police during an infamous raid on New York’s Stonewall Inn in 1969, or the Cowgirls of Color, an all-Black rodeo team from Maryland. Other Atlantican motifs emerge through Bey’s casual banter with friends. That monument devoted to chicken wings? The artist says its invention was sparked by a disagreement she had with a friend about chicken wings: “We were like, imagine if this were the biggest disagreement we ever had?”

So she imagined that Atlantica’s only war was one fought over chicken and that this conflict, naturally, generated an important memorial. In the exhibition, it is represented by a work titled “Poulet Wing War Memorial Park,” a collage that shows chicken pieces emerging from a vast desert landscape. It is surreal and hilarious.

A quilt becomes a painting at the California African American Museum in L.A.’s Exposition Park.

Her father’s alien tale fed her work. It has also fed her intellectual interests.

Bey is a film buff as well as a devoted reader of speculative fiction. On her nightstand are Octavia Butler’s “Parable of the Sower” and Nnedi Okorafor’s “Remote Control.” And the title of her show at CAAM is inspired by one of her favorite novels: “The Gilda Stories” by Jewelle Gomez, about a Black lesbian vampire and the realities she is forced to contend with over her unnaturally long life.

“My African American father is a huge sci-fi nerd,” Bey says. “I found out in college that a lot of the stories he told me as a kid were actually ’80s sci-fi movie plots.”

If an interest in sci-fi inspired Atlantica’s premise, it’s her observations about tourism that help give the show its form.

Bey may have been born in the United States, but she retains close connections to the Bahamas, where she still has family and friends, and she identifies as Bahamian American. Tourism is one of the Bahamas’ principal economic engines, and Bey is all too familiar with its abuses: low wages and 12-hour shifts at outposts that are outwardly purveying luxury to the world. “The first job I had was prepping food in the family restaurant to serve to tourists,” she says. “Tourists didn’t care about the natives. One half of the island is having a good time. On the other, people don’t have electricity.

“I see tourism,” she adds, “as a new form of slavery.”

Bey, however, is interested in tourism’s design — such as the peppy photographs that greet travelers at airports after they disembark from their flights. “In Nassau, when you land, you get these historical portraits and then these great restaurants and this beach you can lay on,” she says. “The only time you see Bahamians in vacation advertisements is when they are serving someone.”

A moving exhibition on Black spirituality, the AOC effect on political design, symbols of Los Angeles. And should Blue Boy hit the road? Our arts newsletter

“Atlantica, the Gilda Region” takes its form from that architecture of arrival: Visitors to CAAM’s gallery wind their way through images of vibrant, larger-than-life figures.

In Bey’s hands, however, this is no ordinary airport transit.

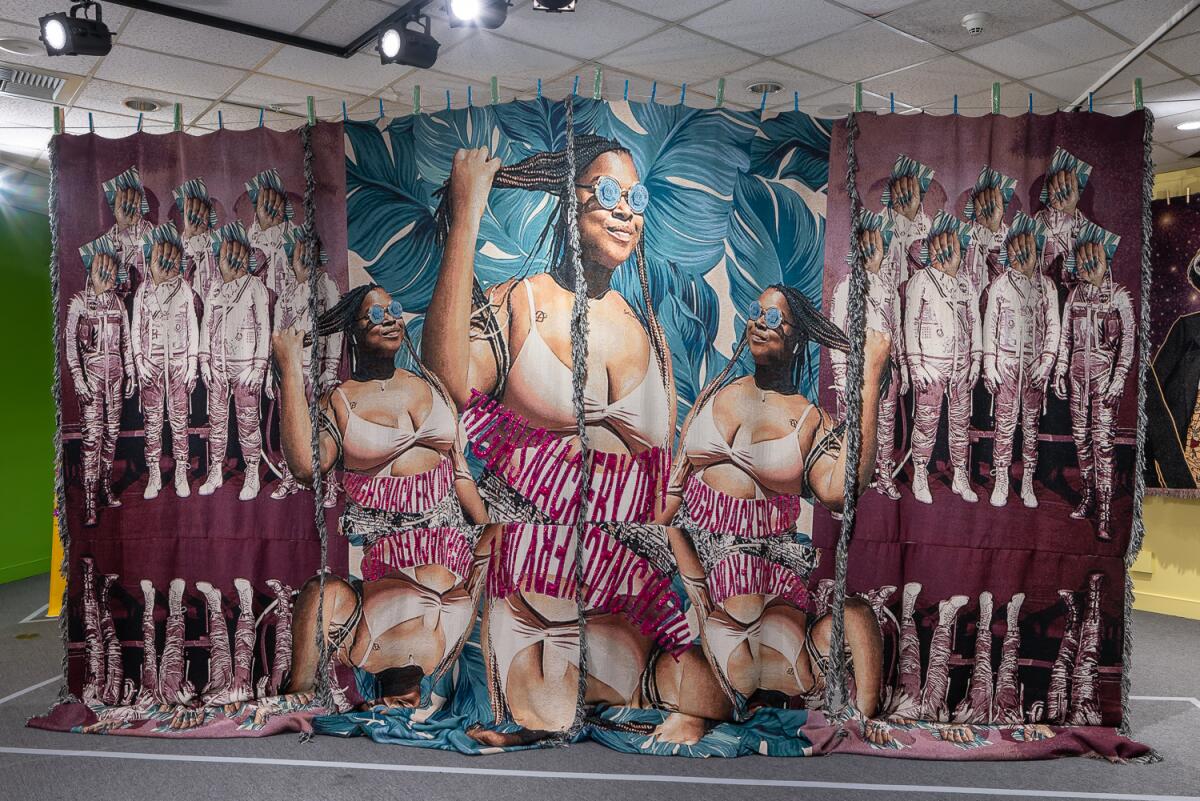

To enter the gallery is to be absorbed into a sumptuous, otherworldly space. The artist renders some of her collages on large, digitally woven blankets, which not only give the color palette a supernatural cast; the material also feels as if it might just envelope the viewer. Other juxtapositions combine high-gloss photographs with frames wrapped in purple faux fur. Everywhere, there is sensuousness: deeply saturated colors and curving bodies and curving landscapes adorned with sparkle and quilted with bright swatches of African fabrics (which the artist sources directly from female-owned businesses in West Africa).

The combined effect is absolutely delirious.

“April’s vision is a world where all Black people are loved and accepted and where they are free to express themselves and where their pleasure is not policed,” says CAAM’s executive director, Cameron Shaw. “And that is an important vision right now.”

If the show is about an imagined journey, it also marks a journey for artist and museum.

Bey first showed with CAAM in 2015 in the group exhibition “Hard Edged: Geometrical Abstraction and Beyond,” organized by curator Mar Hollingsworth, who also put together the artist’s current show (and who just retired after 23 years at the museum).

“Hard Edged” featured an early work by Bey that she produced when she was still a graduate student at Cal State Northridge, where she received her master’s in fine arts in 2014. The piece, “Picky Head,” consisted of a wall covered in images of Black men and women wearing their hair in natural styles. Over this wallpaper, Bey used gallons of relaxer to spell out the words “PICKY HEAD” — Caribbean slang for someone with unkempt hair — in large white capital letters. The project was part of a series Bey did as a graduate student exploring the politics and aesthetics of Black hair and the natural hair movement at a time in which she herself was ditching the relaxers and growing out her natural hair.

I saw that show, and Bey’s piece remains seared in my memory: Over time, the relaxer ran down the walls, stripping the pigment from the images — literally whitening them in the process. And the smell of the relaxer, which was generously applied, could practically make a viewer’s scalp burn. The imposition of white beauty standards on Black bodies? It can be toxic.

Since then, Bey’s profile in the art world has risen. She is now represented by a pair of galleries — Gavlak in Los Angeles and Tern in the Bahamas — and CAAM recently acquired one of her works for its permanent collection.

But the concerns she articulated half a dozen years ago remain present: of creating a space where Black women and queer people can simply be themselves.

“I’m trying to get everyone to think in an elevated, evolved way,” says Bey. “If the aliens came in to check on us, they might be, ‘Omigod, you still have race? You still have gender?’”

People of Earth: We still have a long way to go.

‘April Bey: Atlantica, the Gilda Region’

Where: California African American Museum, 600 State Drive, Exposition Park, Los Angeles

When: Through Jan. 17

Info: caamuseum.org