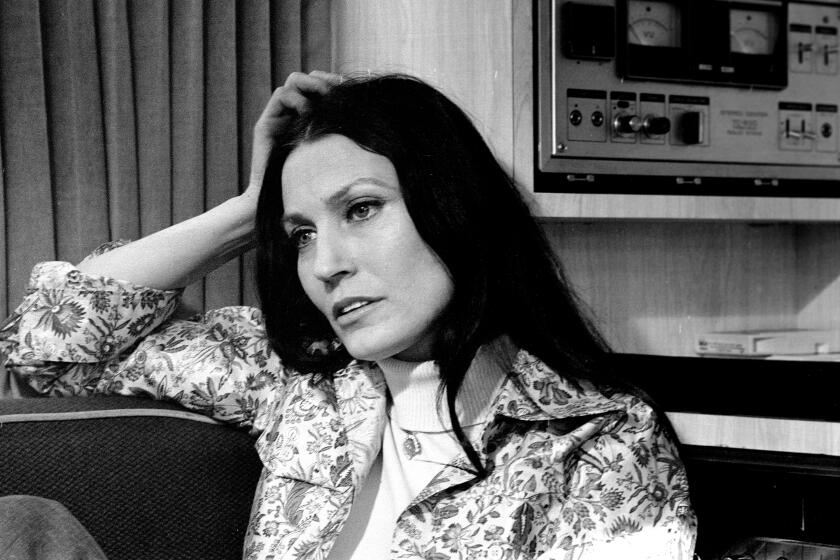

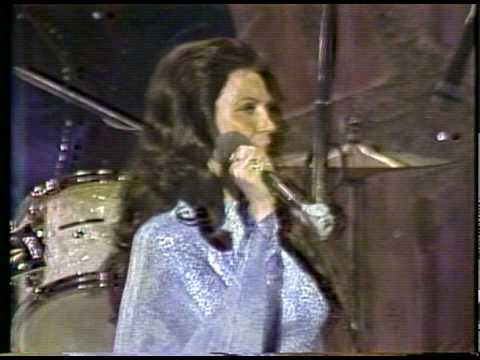

Loretta Lynn, coal miner’s daughter who transformed country music, dies at 90

- Share via

The winding road that country music traveled had long ago been paved over by men when Loretta Lynn stepped on stage and — with grace, charm and ample force — countered centuries of patriarchal attitudes through her music.

Lynn quickly became a trailblazer and controversial figure in the country music scene when she emerged in the early 1960s, writing and singing songs that envisioned a far different path for women than the one outlined in “Stand by Your Man,” the signature song of the era’s other major female figure, Tammy Wynette.

Lynn’s songs staked out a new world order of domestic life in rural America, one where submissiveness and second-class status would no longer be tolerated. “Don’t Come Home A-Drinkin’ (With Lovin’ on Your Mind)” was the title of her first No. 1 hit in 1966, just the beginning of a string of songs that brought to the traditional-minded world of country music changes that women were just starting to demand in the dawn of feminism.

Forever a Kentucky coal miner’s daughter, Lynn died Tuesday of natural causes at her home in Hurricane Mills, Tenn., her family said in a statement. She was 90.

Over her groundbreaking half-century career, Lynn, who died on Tuesday at 90, could embody both the pain of betrayal and the thirst for revenge.

Lynn was arguably the single most important female figure in postwar country music. Her defining 1970 hit “Coal Miner’s Daughter” lent its title to her bestselling 1976 autobiography and the subsequent feature film in 1980 for which Sissy Spacek won the lead actress Academy Award for her gritty portrayal of Lynn as a woman of rural resilience who spoke to the daily struggles of working-class women.

“Loretta forever changed the notion of what a country ‘girl singer’ should or could be,” wrote the late music journalist Chet Flippo in 2010. “She wrote about hitherto forbidden topics: Birth control! Female power! Self-determination! And she attracted a lifelong audience of women listeners who had never been directly addressed before by country music — either the music industry or the radio industry.”

Her song “The Pill” in 1975 touted the benefits of birth control to a segment of society that had long been accustomed to women giving birth on virtually an annual basis as long as they were physically able. Lynn wrote from experience: By the time she was 18, she’d already had four children with her husband, Oliver Lynn, whom she usually referred to by his nickname “Doo.” “The Pill” was banned at numerous country radio stations and brought her criticism from the male-dominated music industry.

“I’m glad I had six kids because I couldn’t imagine my life without ’em,” she wrote in “Coal Miner’s Daughter.” “But I think a woman needs control over her own life, and the pill is what helps her do it.”

She countered the Bible Belt commandment of “till death do us part” in “Rated X,” a 1972 No. 1 hit that had the nerve to discuss divorce openly, recognizing the double standard of a stigma historically applied more often to women than men.

She also projected the persona of a no-holds-barred woman who could take care of herself and was in no need of waiting to be rescued by a man in tough-as-nails hits such as “Fist City” and “You Ain’t Woman Enough,” which served up warnings to other women who might be thinking of setting their sights on her man.

The template Lynn created stood in stark contrast to the long-suffering role women were often relegated to in earlier generations as typified in Kitty Wells’ “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels.” And it influenced the work of successive generations of singers including Emmylou Harris, Reba McEntire, Patty Loveless, Shania Twain and Martina McBride on through the latest class of assertive female singers and songwriters including Carrie Underwood, Miranda Lambert and Taylor Swift.

Lynn’s 2004 collaboration with rock music iconoclast Jack White, “Van Lear Rose,” brought her some of the best reviews of her long career and introduced her to a younger audience. White and his partners in the rock band the White Stripes recorded “Rated X” on their 2001 album “White Blood Cells” and subsequently struck up a friendship with the song’s originator.

On her 2005 “Van Lear Rose” tour, Lynn played clubs more accustomed to hard rock than traditional country. The album earned her two Grammy Awards, including country album of the year.

She was the first female country artist to achieve a gold album, signifying sales of 500,000 copies of her 1963 debut album, “Loretta Lynn Sings,” and in 1973 she became the first country artist to appear on the cover of Newsweek magazine. She was awarded by Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Obama in 2013.

When she was in contention for the entertainer of the year award from the Country Music Assn. in 1972, she was advised that if she won, she should not touch Charley Pride, the Black country singer who was to present the award, to preserve her image among country’s largely white, Southern audience. She ignored the warning when she did win and hugged Pride.

LeAnn Rimes, Mickey Guyton, Kacey Musgraves and Dolly Parton are among the many country music stars paying tribute to Loretta Lynn, who died Tuesday.

Loretta Webb was born April 14, 1932, in Butcher Hollow, Ky., which was pronounced “Butcher Holler” by locals. For years she would not reveal her date of birth, which was later confirmed by Kentucky public records.

“When I was born, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was the president for several years. That’s the closest I’m gonna come to telling my age in this book, so don’t go looking for it,” she wrote in “Coal Miner’s Daughter.”

She was the second of eight children of Melvin and Clara Webb, and as she grew up was often called on to help care for her younger siblings. “I’d sit on the porch swing and rock them babies and sing at the top of my voice,” she wrote in her autobiography.

Her father worked road construction under the Works Progress Administration launched by Roosevelt to create jobs during the Depression. As the economy improved in the late ‘30s, he got a job in the coal mines, setting the stage for her future autobiographical song.

Despite the poverty the family endured, Lynn recalled a happy childhood. “We were poor, but we had love,” she sang in her iconic hit “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” “that’s the one thing that Daddy made sure of.”

The family listened to radio broadcasts from the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, but Lynn later wrote, “I can’t say that I had big dreams of being a star at the Opry. It was another world to me. All I knew was Butcher Holler — didn’t have no dreams that I knew about.”

In fact, she didn’t start singing professionally until well after she and Oliver Lynn married in 1948.

“I told Momma, ‘I’m getting married so I won’t have to rock all them babies,’” Lynn told Newsweek. “Then bang, bang, bang, bang, I had four children in four years.”

When work in the coal mines began to dry up after World War II, the young couple relocated to Washington state, where her husband had once lived. He bought her a guitar after hearing her sing along with the radio.

“I was proud to be noticed, to tell you the truth, so I went right to work on it,” she wrote in her book. She always credited her husband with launching her career in music.

“It wasn’t my idea,” she wrote. “He told me I could do it. I’d still be a housewife today if he didn’t bring that guitar home and then encourage me to be a singer.”

She also began writing her own songs so she’d have something to sing besides the Kitty Wells songs and other country hits of the day.

Lynn got her big break from Bakersfield country musician Buck Owens, who was hosting a television show in Washington at the time. She won a talent contest on the show and a Vancouver, Wash., businessman who saw her performance put up money so she could make a record.

She traveled to Los Angeles and recorded her own song, “I’m a Honky Tonk Girl,” which quickly vaulted her into the country Top 10 in 1960. That allowed her to move to Nashville, where she soon began performing on the Grand Ole Opry. She raised hackles there for bringing along her own band that included drums, which ran counter to the Opry’s exclusive reliance on acoustic stringed instruments such as guitar, fiddle, mandolin, banjo and upright bass.

While working at the Opry she became close friends with Patsy Cline, one of its biggest stars, and began to open shows for Cline when she went on tour. Lynn was devastated when Cline was killed in a 1963 plane crash.

But Lynn’s career soon equaled and then eclipsed Cline’s as she went on to score 16 No. 1 country hits, five of them in collaboration with her longtime duet partner Conway Twitty. Among her chart-topping hits was her 1977 version of “She’s Got You,” the Hank Cochran song that in 1962 had given Cline her biggest hit.

From 1960 through 1981 she put 78 songs on the country singles charts, 53 of them making the Top 10.

Some of her songs that spewed venom at lying, cheating men were indeed drawn directly from her life with Oliver, yet she remained unfailingly devoted to him throughout his life.

“The more you hurt, the better the song is,” Lynn told the New York Times in 2016. “You put your whole heart into a song when you’re hurting.”

As her husband’s health deteriorated in the 1980s, she put her career on hold to care for him and largely dropped out of public sight until after his death in 1996, with the exception of the “Honky Tonk Angels” country superstar trio album she recorded in 1993 with Dolly Parton and Wynette.

Though she suffered a stroke in 2017, Lynn continued recording into her 80s, working with one of her twin daughters, Patsy, as co-producer along with longtime family friend John Carter Cash, the lone child of singers Johnny Cash and June Carter.

They worked primarily in the Cash Cabin Recording Studio in Hendersonville, Tenn., about 90 miles east of Lynn’s longtime home in Hurricane Mills, Tenn., where she opened a restaurant bearing her name. Whenever Lynn was up to it, she would work, stashing away what was said to be least 10 albums’ worth of material that would guarantee her catalog would continue to grow long after her death. In 2021 she released her 50th studio album, “Still Woman Enough.”

“I’m going to keep working till they put me down,” Lynn told The Times in 2016. “But I ain’t figurin’ on going any time soon.”

Lynn is survived by her daughters Patsy Lynn Russell, Peggy Lynn, Clara (Cissie) Marie Lynn and her son Ernest Ray Lynn as well as 17 grandchildren and numerous great-grandchildren. Her son Jack Benny died in 1984 while trying to ford a river on horseback and her first child, Betty Sue, died in 2013 of complications from emphysema.