Always just enough and never too much: The steadfast genius of Charlie Watts

If the other guys were rolling, somebody had to be the stone.

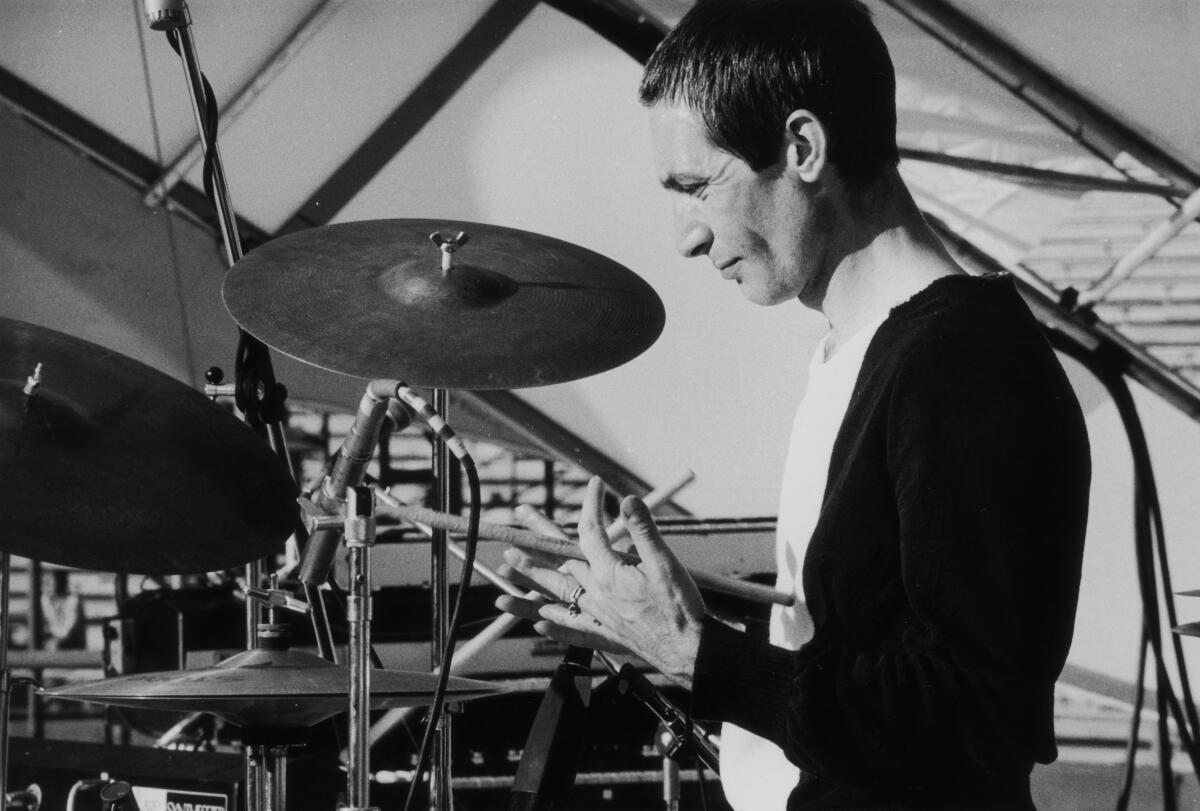

That was the job Charlie Watts saw for himself — and then carried off with incomparable style for more than half a century — as the steadfast drummer of the Rolling Stones, the world-famous (and maybe world’s greatest) rock ’n’ roll band in which he kept deeply reliable time behind his flamboyant bad-boy bandmates.

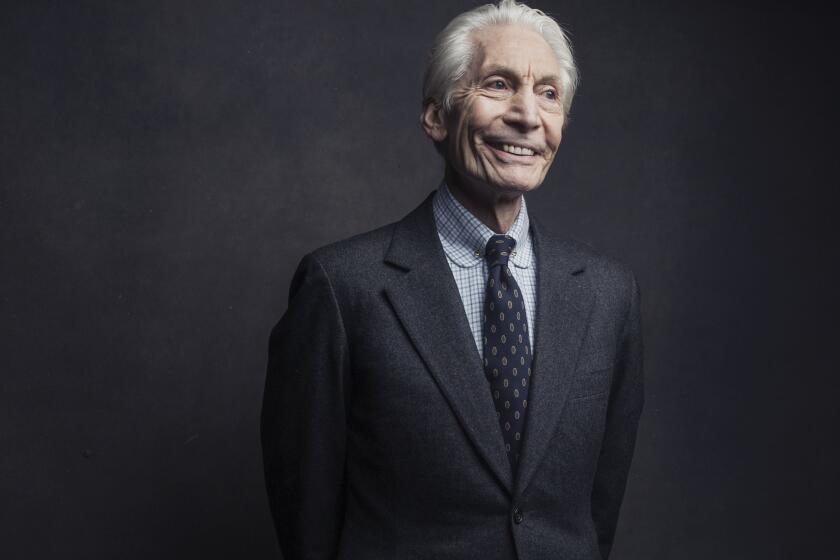

Onstage, Mick Jagger would wag his bum as he sneered about his wealth and taste; Keith Richards would roam around caressing his guitar in a way that felt vaguely indecent. And then there was Watts, never less than crisply dressed, a ramrod presence at his stripped-down kit.

Charlie Watts, the drummer who anchored the Rolling Stones throughout their reign as the World’s Greatest Rock & Roll Band, has died at age 80.

He’d come up as a jazz drummer but put aside any tendency toward flash when he joined the Stones in the early 1960s. “Mick and Keith write the songs, the music is theirs,” he said decades later in an interview. “So the bottom line is, if they want me just to go wham-wham-wham, then that’s what I’ll do.

“I think it should be whammity-whammity-bam, but I’ll do wham-wham-wham.”

Yet to suggest that Watts, who died Tuesday at age 80 — having never missed a Stones gig, it should be said — played simply or minus appreciable flair is way off the mark. Watts provided a groove and swing that distinguished the Stones from the get-go; his propulsive beat in their youthful covers of “Not Fade Away” and “It’s All Over Now” made the music jump in a sexy, slightly dangerous way that transcended the record-nerd scholarship the songs actually represented.

And when Jagger and Richards began writing their own songs, Watts figured out how to turn their meanings into rhythm. Listen to his work in “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” a relentless forward thrust so evocative of Jagger’s longed-for you-know-what that the rest of the band quits playing around the two-minute mark just so we can revel in it.

Charlie Watts, the drummer who anchored the Rolling Stones throughout their reign as the World’s Greatest Rock & Roll Band, has died at age 80.

The Stones’ catalog is filled with countless examples of Watts’ clever scene-setting: the beat hammering away like a migraine in “Paint It Black,” the almost satirically louche funk groove in “Honky Tonk Women,” the snare that keeps cracking like a gunshot in the death-obsessed “Gimme Shelter.” He could play fast, as in “Rocks Off” and “Mixed Emotions” and “Bitch,” and he could play slow, as in “Tumbling Dice” and “Beast of Burden” and “Wild Horses,” the last of which he barely keeps from sliding into the ditch it seems destined for.

Whatever he was doing, though, it was always just enough and never too much — an economy that suited a drummer who said he learned to play on an instrument he made himself out of a banjo. (It probably also helped, once he could afford to buy any drum he wanted, that he maintained a number of showoff-ier jazz-combo side projects.)

The essential tastiness of Watts’ playing — and his eagerness to let others in the band do the peacocking — allowed the Stones to adapt their approach to whatever was happening in pop. He knew how to push the music toward disco, as he did in the late ’70s with “Miss You,” without making the band sound desperate, and he knew how to push it just as believably toward punk during the same era with “When the Whip Comes Down.” Jagger and Richards could go all-out on vocals and guitar; Watts kept the Stones sounding like the Stones.

Looking like them too: Watts, who’d worked as a graphic artist before joining the band, helped shape the Stones’ visual imagery in merchandise and stage sets; he co-designed album covers and even appeared on the cover of a couple of them — including the 1970 live album “Get Your Ya-Ya’s Out!” — despite his avowed disinterest in the spotlight. In concert, his frowning expression and rigid posture behind the drums called to mind Sam the Eagle from the Muppets — a welcome comic counterpoint to all the rock-star preening going on around him.

His deadpan attitude was another valuable antidote to the natural hucksterism of his bandmates. On the one occasion I spoke with Watts, ahead of a 50th-anniversary tour the group mounted in 2012, he scoffed when I told him that guitarist Ronnie Wood had hyped up the group’s five-hour rehearsals and promised that the band was “up to a point we’ve never been before.”

“I don’t know what he’s talking about,” Watts said in his clipped English accent. “We have a lot of songs. You start off playing a hundred, then get it down to 25.”

As usual, he was forgoing the whammity-whammity-bam.