It is a Saturday night in late May, and Joni Mitchell finds a seat in her living room, a high-ceilinged space with a pool table, an array of guitars, a grand piano and a generous collection of her paintings. Her face is filled with promise and a touch of mischief. Tonight is the latest edition of “Joni’s Jam,” the first since the world opened up a bit.

In 2018, in town for a show, singer-songwriter Eric Andersen had visited Mitchell’s Bel-Air home with his band. The house was quiet then. It was just a few years after the sudden brain aneurysm that stilled Mitchell’s voice and brought her the medical verdict that she’d likely never walk again. It wasn’t the first time she’d heard that. After being diagnosed with polio at age 9, she declared she’d walk again. Sixty-one years later, at a similar crossroads, she vowed the same thing. Often asked if she’d sing again though, Mitchell’s response was usually less promising. A smile, a small shake of the head.

“Oh, that’s gone,” she’d say, meaning her voice.

But Andersen played live music in her living room that night, and while Mitchell’s voice was absent, it was the sound of musicians and the camaraderie that this self-professed “rowdy” missed. Not long after that, at a dinner with a friend, Grammy-winning singer-songwriter Brandi Carlile, Mitchell suggested she help round up some musicians for a more regular jam session. “Joni’s Jam” would occur from time to time, always with a small group of musician friends like Chaka Khan or Herbie Hancock and maybe some of the “young’uns” who’d wanted to blend in and meet her, like Harry Styles. Joni’s only motto: “Park your pistols at the door.” That meant no phones or video and only one photo — a group shot at the end of the night.

“All right, here we go,” announces Carlile, here for tonight’s jam. She’s flanked by her guitar-and-bass accompanists Tim and Phil Hanseroth. Also present: Elton John, Jess Wolfe and Holly Laessig from Lucius, singer-songwriter Charlie Puth, musician-bandleader Rick Whitfield and pianist Ben Lusher, along with spouses and Laessig’s newborn baby, Oscar. Carlile kicks off the evening with her version of “Carey,” the signature song from Mitchell’s most beloved album, “Blue.”

Six feet away is the artist-composer herself. As Carlile jauntily offers the song with true fan fervor, a warm and familiar voice joins in when the chorus arrives.

“Oh, you’re a mean old daddy,” sings Joni Mitchell, “but I like you … fine.”

On “Blue”’s “All I Want,” Joni Mitchell asked “Looking for something, what can it be?” The answer was Joni Mitchell.

There are whoops and hollers, and nearby on the sofa with husband David Furnish, John shares a look of joyful surprise with the others. That voice. She’s singing again. Soon after, John joins Puth for a stirring version of his own “Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me,” Lucius sings a new song, and Carlile does the same, along with her show-stopper “The Joke.” Near the end of the evening, John serenades Mitchell with a burnished, world-wise version of “Moon River.” “I just want to say,” he’d announced earlier, “this is such a gift to see you doing so well. And to be here, and to tell you how much we love you. … We just love you.”

A goosebumps evening to be sure, but it’s the rousing version of Mitchell singing “Blue’s” “All I Want” with Carlile that might linger longest. “I am on a lonely road, and I am traveling, traveling, traveling.” She wrote the song long ago, but she doesn’t sound lonely tonight.

A couple of nights later, over a rustic dinner featuring Mitchell’s own “Saskatoon stew,” she is still glowing from the event that filled her living room with song. Or perhaps it is the robust physical therapy and swimming session she’s just come from.

“It was a fun evening,” says Mitchell. “I wasn’t sure I would be able to sing. I have no soprano left, just a low alto,” she explains. “The spirit moved me. I forgave myself for my lack of talent.” She laughs. “I’m still playing little clubs.”

It’s a long way Mitchell has come from her early roots in Canada as a young folk singer and art student. She quickly outgrew the often creaky folk standards of the day and began writing her own songs. Judy Collins’ version of Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now” became a big hit, cementing an early songwriting reputation. Hearing Leonard Cohen’s “Suzanne” inspired Mitchell to head for even deeper emotional territory. Her next works were “Clouds” and “Ladies of the Canyon.” Both brought further acclaim. While songs like “For Free,” “Circle Game” and “Woodstock” had all shown growing sophistication, it was the stark emotion of the next album that would catch many by surprise.

Released this week in 1971, “Blue” would become a watershed moment in modern songwriting. Then just 27, Mitchell had written her most personal work yet. The subject was love, captured in all its giddy glory and beautiful agony, laced with the fresh sound of a dulcimer guitar. The intimate tone and the raw nature of the songs would later give permission to other songwriters to go deeper with their work. From John Lennon to Prince to Phoebe Bridgers and just about any songwriter who picks up a pen, the ripple effect continues to this day.

Mitchell has spent much of the pandemic curating a series of archival releases that will span her genre-busting career. With the help of her longtime friend and associate Marcy Gensic, she’s been approving rare live takes, outtakes, demos and remastered versions of tracks from her first four albums, in what will become “Joni Mitchell Archives Vol. 2: The Reprise Years (1968-1971),” set for release Oct. 29. Combing through the treasure trove has kept her busy, and with regular therapy sessions accompanied by helper-friends, her days are often joyous. She walks with little help and a bounce to her steps, often to the sounds of Chuck Berry or her favorite song of late, the international dance hit “Jerusalema.”

Once judgmental of her earliest songs being “the work of an ingenue,” these days Mitchell has a more holistic view of her peerless body of work. (Her verdict on “Ladies of the Canyon”: “Not bad.”) Often Mitchell listens on a Bose system in her kitchen while playing her own version of solitaire. “Joni’s solitaire” is an invention not unlike the artist herself. There is no winning or losing. There’s not even an ending. It’s a study in the elegance of play.

We asked 10 of our favorite artists to each choose one track from Joni Mitchell’s ‘Blue’ and describe what makes the song and artist so indelible.

Cameron Crowe: You often hear from fans and artists about how much “Blue” meant to them. What does “Blue” mean to you?

Mitchell: Sometimes I wonder why it got all the attention, and not my other “children,” you know? “Court and Spark,” “Hejira.” The writing’s pretty good on “Hejira.” I think they all got pretty good from “Blue” on. Like all of my albums, “Blue” came out of the chute with a whimper. It didn’t really take off until later. Now there’s a lot of fuss being made over it, but there wasn’t initially. The most feedback that I got was that I had gone too far and was exposing too much of myself. I couldn’t tell what I had created, really. The initial response I got was critical, mostly from the male singer-songwriters. It was kind of like Dylan going electric. They were afraid. Is this contagious? Do we all have to get this honest now? That’s what the boys were telling me. “Save something of yourself, Joni. Nobody’s ever gonna cover these songs. They’re too personal.”

What were the sessions like for the album?

It’s the only session I had like that, where we locked the door. I felt I was in a very vulnerable place. I had this dream then that really stayed with me. I’m in a room with bentwood stackable folding chairs, and there’s a bemused audience watching a group of large women in rolled-up nylon stockings, playing tubas and trombones. And I’m in the audience too, except I’m a clear cellophane bag of exposed human organs. Just a bag of human organs with a heart beating in the center. I felt like that. I felt exposed, like I couldn’t have people in the room witnessing me. I couldn’t really be around people. I felt too vulnerable. I felt like everybody could see into me and see that I was suffering. I don’t remember even why I was suffering so much. A lot of the album was written in that frame of mind. The image from that dream is still the best metaphor for how vulnerable I felt.

And out of it comes a slew of achingly autobiographical material. Your longtime engineer and creative ally Henry Lewy must have seen that vulnerability coming early on. What did he say when he heard the material?

“Lock the door.” And that’s what he did.

There’s plenty of joy in the album too.

Some of it was written while I was having great adventure. But, you know, I was also feeling a great sense of loss because I’d broken up with Graham Nash. And that was still hanging over me. ’Cause I thought with Graham and I, our relationship was very strong. I thought that it was the last one I’d have. And so I disappointed myself when that wasn’t so, and that’s why I was so sad at that time. I was sad I hadn’t gone the distance.

The initial response I got (for “Blue”) was critical, mostly from the male singer-songwriters. It was kind of like Dylan going electric. They were afraid. Is this contagious?

— Joni Mitchell

You take off for Greece in early 1970, and thus begins your adventure of living in the Matala caves. Matala becomes the setting for some of the most beloved songs on “Blue.” Why Greece?

I was ready for an adventure. Penelope was a girl I knew and she was going, and I asked if I could tag along. We were both friends of Leonard (Cohen), so we wanted to see his island (Hydra). I brought a flute and my dulcimer. In Hydra, I climbed to the top of a mountain and played among the goats and sheep with my flute. In Athens we went to this place where the poets hung out. It was like a moving crap game because the junta were busting up public meetings. There was a kind of an apple-crate guitar there that some of the poets played. I bought it off them for $50. I was so missing my guitar. We went into the Athens underground, and I sat on the ground down there, like a busker. I played, and people threw money at me.

Was anybody keeping tabs on you? Had you cut ties with everybody back home?

Nobody knew where I was back home or how to get hold of me. Eventually I found a phone to let everyone know that I was still alive and kicking. [Laughs.] But everywhere we went in Greece, people would say to us, “Sheepy, Sheepy, Matala Matala!” We didn’t know what that meant. It meant, “Hippie, hippie, go to the caves of Matala! That’s where your kind are!” So we rented a car and took a ferryboat, and we arrived there. It was dark. We went down to the water’s edge. And when we were looking out towards Turkey, Penelope started thinking about her namesake, you know, Penelope, the wife of Ulysses. Just as we were talking, we heard an explosion, and when we turned around we saw Cary (Raditz) being blown out the door of a restaurant. He was a cook, and he had been lighting the stove and it exploded. I said to Penelope, “What an entrance! I’ve got to go and meet him.” So we walked over there, and he was dressed in a white turban and white shirt and white baggy pants like gauze. He’d come from the city of Banaras in India. The explosion had singed all the hair on his arms and legs. It went right through his clothes. And that’s how I met Cary. He exploded into my life, just like that.

And Cary becomes a kind of partner in crime, protector, raconteur as you lived for a time in the caves of Matala. Why was he a “mean old daddy”?

When I arrived in Matala, there was a bit of a fuss, you know, and people would say, “Donovan is coming on a sailboat!” and stuff. Like it was going to be a star invasion. [Laughs.] And Cary watched all of his friends go kind of gaga over me. He resented me for that. He was always trying to put me in my place in front of his friends. His friends were cuckoo. He wanted to show that he wasn’t going to be intimidated by celebrity. We’re still friends. He was here recently.

The song “Carey” becomes that very rare thing — an affectionate goodbye song. Cary himself says he knew you’d been talking about being homesick, but he didn’t realize you were actually saying goodbye until he heard the song, which you played to him on his birthday.

It was a good goodbye. I’ve never had a problematic ending to my relationships. After my first husband, I learned to choose more carefully. [Laughs.] I don’t like goodbyes so much. I like hellos.

Joni Mitchell might not have wanted to be the glamorous bard of women’s rising consciousness, but with “Blue,” she became just that.

What was it like finally coming home?

I was happy to be home. I love that Laurel Canyon house, you know. It was welcoming. All the houses that I’ve lived in have given me that feeling. But it was bittersweet. I looked forward to coming back and meeting up with [Crosby, Stills & Nash], you know. They’d been my hangout buddies. I was the bad guy for leaving Graham. I’d lost my homies.

I’m not a weeper. I’m a snarler. I just put all the weeping in the words.

— Joni Mitchell

After the very first album produced by David Crosby, and one track with Paul Rothchild, you’ve always produced yourself.

I had an interesting thing happen early on. I always loved Buffy Sainte-Marie. I loved how she would close her eyes when she sang. … She had great movement, and she never hit the mic with her nose! I never got quite as good at it as she was, but I loved that movement. The night I met Henry Lewy, I was set up with a producer; it was the producer of the Doors, Paul Rothchild. And he couldn’t get a sound he liked ’cause I was swaying around. He’d say, “You have to stay still!” He actually taped my feet to the studio floor. He took all the joy out of it for me. And then he said to me, “I’ve got to go produce the Doors for two weeks.” I thought, “OK, good.” So I said to Henry, “It’s just you and me. Can we finish the album ourselves in two weeks?” He smiled. “I think so.” Henry and I were like the dream team, ever since. It was so loving and comfortable, like family. It’s the right environment for me creatively. We had shorthand, it got kind of cryptic. I had nicknames for all the gizmos. People would visit a session and ask Henry, “Do you know what she’s talking about?” And he would say, “I know exactly what she’s talking about.”

Is there anything you want to say about “River”?

No, just, you know, it expresses regret at the end of a relationship. That’s about all. It’s about being lonely at Christmastime, which is one reason for its popularity, I think. So many people are lonely at Christmas. I heard somebody on the radio, or maybe it was in print, but they were ragging on “River.” You know, it has been recorded a lot and called a Christmas song. And they were grumbling about it. “This is not a Christmas song!” And I thought, “It’s absolutely a Christmas song. It’s a Christmas song for people who are lonely at Christmas! We need a song like that.”

Do you ever make yourself cry when you write?

No, never. I’m not a weeper. I’m a snarler. I just put all the weeping in the words. The words are the weeping.

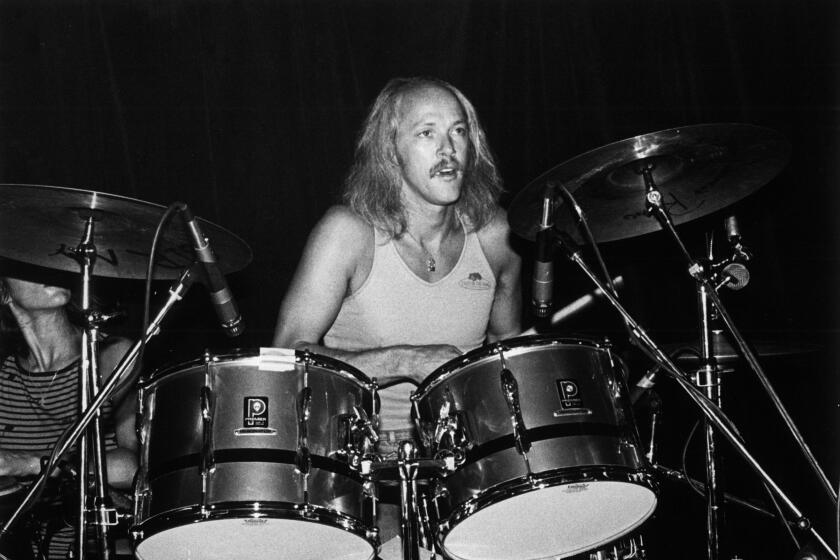

L.A. session drummer extraordinaire Russ Kunkel on working with his friend ‘Joan’ and what people don’t realize about her musical chops.

And yet, when you recorded the symphonic “Both Sides Now” in 2000, you’ve said that all those London Symphony Orchestra players were crying.

I didn’t expect that. That was really shocking to me, in a beautiful way. It made me sing differently. I mean, it sparked me into a deeper performance. That’s why I think that’s the definitive performance of that song. It’s how it should be.

How do you prepare for a big performance like that? Do you make yourself some tea or have a vocal warm-up exercise? Do you have a ritual? (Mitchell shakes her head no.) You just roll in and do it?

Like a plumber.

I was watching you sing songs from “Blue” the other night and wondered: Is it like going through old photos and thinking “I was a different person then”?

No, I’m the same person. It’s all still very present for me. I mean, I’ve changed styles and things, but not the core of who I am, ever. My old friends see me as being the same as I was when I was a teenager, and so do I.

I don’t know if you’ve seen the recent documentaries on Laurel Canyon. As the person who is often portrayed as the “Queen of the Canyon,” what’s one thing they got right and one thing they got wrong?

I didn’t really see them, but I’ve heard the laundry list of people who “lived” there. They didn’t seem to know who really lived in Laurel Canyon. David Crosby didn’t. Graham Nash did. Frank Zappa did. Zappa lived two doors down from me. My kitchen table overlooked his backyard, which is a pond that sometimes would have white ducks … and a raft, which would occasionally have naked girls floating on it. When my mother was there, she looked down and saw the naked girls float by in his pond. She was horrified. Plus, I had all my paint cans stored next to some heaters in the back of the house. She said it was a fire hazard and that freaked her out too. Oh, and my next-door neighbors were junkies who eventually burned their house down. One night while she was there, there was somebody on my roof, and there were footsteps. It was the cops spying on the junkies, and I went to the back door and yelled at them. She didn’t like that either. But it was a magical place. And when the house next door burned down, the flames climbed onto my side of the house, they blistered the paint, scorched the front door — it’s still scorched — and then they went onto my roof. At that exact point, a wind came up and blew the fire off the house. The house is magic.

What was your first reaction to watching Graham Nash write “Our House” while living in the same house?

I thought it was beautiful. It captured that day. Our relationship was warm and cozy and loving. Sometimes I get sensitive or worried, and it might bother the man I was with. But not Graham. He just said, “Come over here to the couch; you need a 15-minute cool-out.” And then we would snuggle. It’s a beautiful memory.

I’ve changed styles and things, but not the core of who I am, ever.

— Joni Mitchell

In August of 1970, you played the Isle of Wight festival and debuted some of the “Blue” material. But the festival was a near disaster, and before long you retreated to build a cottage in the Sunshine Coast of British Columbia.

I decided I was going to be a hermit. I don’t mind isolation. I’m good with isolation. I loved my little stone cottage. The pine trees and the ocean and the brine is just so distinctive, you know? I guess I’m a set designer. I create environments I enjoy.

How did that period of retreat end for you?

About a year later. It was autumn and the trees were yellow, and they were reflecting on this black water. I was at the water’s edge, just getting some sun. I spontaneously dove in the water. I was underwater and something happened. I broke through the surface into this beautiful black and blue and yellow world. And I just laughed. And I thought, I’m healed. I got my sense of humor back! Suddenly it was all humorous, that vulnerable, transparent time was over. I felt the world all around me. I’m healed. That’s how that whole “Blue” chapter ends, and it’s also where the next one begins. With laughter. Onward and upward.

Well, if Saturday’s jam was any indication, this year will be a new chapter for you too.

You know, it’s amazing to me, looking at all of this attention my work has gotten recently … the response when I’ve gone to Clive Davis’ Grammy parties too. He announces me, and that audience gives me this thunderous applause. I’m always so moved when people tell me how the music has affected them. It’s amazing to me that after everything, in spite of the criticism, that the intimacy paid off big time. It really did help people face their own intimacy, you know?

Fifty years later, that’s what lasts.

Truth and beauty. That’s what I hope to deliver.

Cameron Crowe is a writer-director who first interviewed Joni Mitchell for a Rolling Stone cover story in 1979.