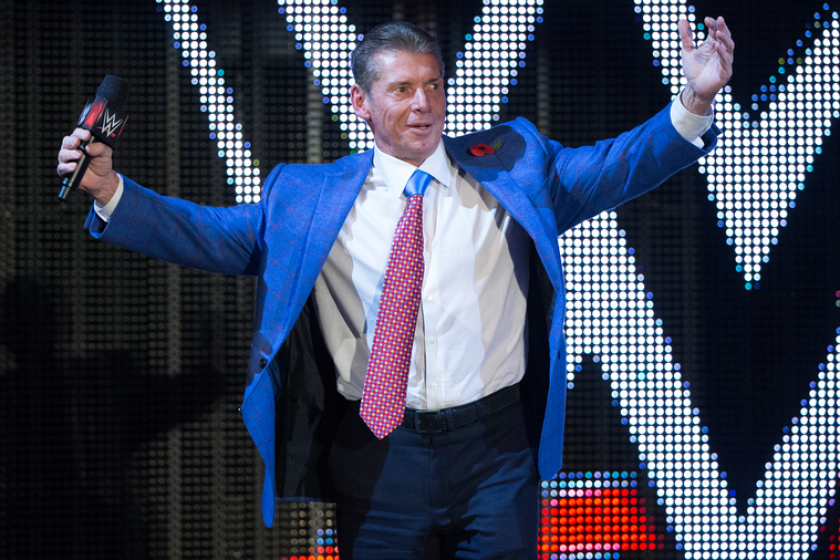

In the annals of remarkable turnarounds, Vince McMahon appeared to engineer a rather swift and astonishing one for himself.

In January, McMahon had orchestrated his return as World Wrestling Entertainment’s (WWE) ringmaster.

The move came just months after his humiliating exit, following the scandalous revelations reported in the Wall Street Journal that he had paid millions in hush money to multiple women to squash allegations of sexual misconduct, which he denies.

But McMahon — who regularly spits out acerbic macho quips like, “I have balls the size of grapefruits, and come this Sunday, you’ll be spitting out the seeds” — wasn’t finished. He followed that maneuver by executing his most audacious play yet.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

In April, he agreed to merge the WWE with the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) to form a new publicly traded company worth a staggering $21.4 billion. The new entity, which officially launched this month, is controlled by Endeavor Group, the entertainment giant headed by Hollywood power broker Ari Emanuel. McMahon is staying on as executive chairman of the board.

It was not merely a triumph for McMahon — who went from professional wrestling’s public heel to its face (villain to hero in the industry’s parlance) — but a stunning turn of events in the worlds of sports, media and entertainment, potentially creating a game-changing colossus.

Investor response had been positive. TKO shares, which began trading Sept. 12 , hit $105.53 Tuesday, up 3.46% over its opening price of $102. However, shares have since fallen to $83.79 at the close of trading Friday, down 20.6%.

McMahon boasted that the new company, TKO Group Holdings, was nothing less than a “live sports and entertainment powerhouse with a collective fanbase of more than a billion people.”

Endeavor-owned UFC and WWE will merge to create a fighting sports and entertainment powerhouse led by Endeavor CEO Ari Emanuel. Vince McMahon will remain involved as executive chairman.

But casting a pall over the merger are ongoing investigations by the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Department of Justice into McMahon’s conduct. Last month, WWE disclosed in a regulatory filing that federal law enforcement agents served McMahon with a grand jury subpoena and a search warrant in July.

“I have always denied any intentional wrongdoing and continue to do so. I am confident that the government’s investigation will be resolved without any findings of wrongdoing,” he said in a statement.

“We believe this is a continuation of the investigation that commenced last summer. WWE has cooperated throughout and fully understands and respects the government’s need for a complete process,” the company said in a statement.

Emanuel and McMahon declined to comment further, a spokesperson for TKO said.

Throughout his flamboyant and controversial career, McMahon has faced odds and weathered a raft of personal and professional scandals while building the largest and most influential professional wrestling operation in the world — through a combination of ruthlessness, savvy and luck. Now, however, McMahon, 78, may be facing his toughest match yet.

The government investigations into his conduct come as the WWE is confronting challenges on multiple fronts: Its ratings have dropped since 2018 and its exclusive media rights deals for the flagship “Raw” and developmental “NXT” shows are on the cusp of expiring; it’s also facing lawsuits and competition from a slate of wrestling brands. All of which places the multibillion-dollar merger with UFC, intended to secure McMahon’s legacy and the company’s future, under a cloud.

“Every other scandal he faced was cut-and-dry,” said Leonard Inzitari, a former WWE wrestler known as Mario Mancini. “Here there are multiple issues,” he said, referring to the ongoing federal investigations. “This thing could mushroom into more than just a sex scandal.”

Professional wrestling got its start in the carnival sideshows of the late 1800s.

McMahon, who took over his father’s regional wrestling promotion in 1982, transformed it. With his knack for showmanship and promotion, along with a stable of outlandish wrestlers, over-the-top antics and simple, scripted storylines, (first filled with trash talk and sexual innuendo, and later more family- and ad-friendly fare), he made the once-niche and vulgar amusement into what he termed “sports entertainment” — and a vast money-spinning industry.

Last year, WWE’s net revenue hit a record, $1.3 billion, up 18%. The signature weekly television shows “SmackDown” and “Raw” together average nearly 4 million viewers in the U.S., according to LightShed Partners, while its programming is broadcast in more than 180 countries.

In addition, WWE merchandise — including T-shirts, action figures and a slew of books and video games — contributed $134.5 million in net revenue.

The ‘Walt Disney’ of wrestling

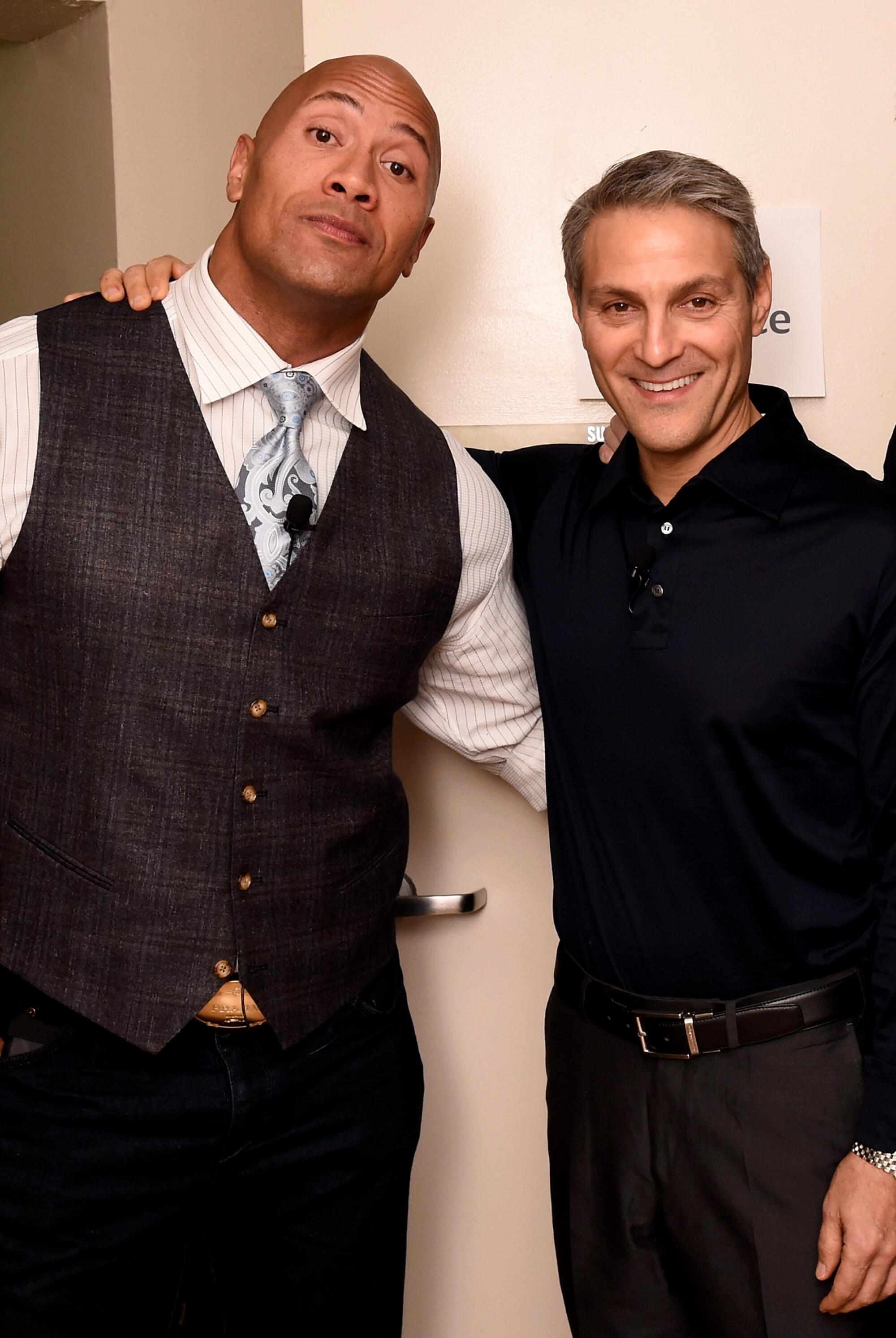

One doesn’t even have to be a casual fan to be familiar with the names Hulk Hogan, Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, André the Giant, Chyna, “Macho Man” Randy Savage, John Cena and Dave Bautista.

In the smoke-and-mirrors world of pro wrestling, McMahon, who once described himself as the “Walt Disney of wrestling,” is so intricately intertwined with the company that his “unexpected loss” has been listed as a potential risk factor for the company in its SEC filings.

If Horatio Alger wore tailored Italian suits, camel-clutched his adversaries and then punt-kicked them to oblivion, his name would be Vincent Kennedy McMahon.

The wrestling billionaire was born in Pinehurst, N.C., and raised in a trailer park without indoor plumbing by his mother and a succession of her abusive husbands.

McMahon once described how, when he was 6 years old, his stepfather, Leo Lupton, an electrician, beat him with a pipe wrench.

“It’s unfortunate that he died before I could kill him. I would have enjoyed that,” he told Playboy magazine.

By the time he was a young teen, McMahon was on his own and by his own account, usually in trouble, stealing cars, getting into fistfights with Marines and running moonshine.

Eventually, McMahon was shipped off to military school in Virginia, where he said that he engaged in numerous acts of insubordination, including feeding the commandant’s beloved dog a laxative. McMahon noted that he was the first cadet in the school’s history to be court-martialed.

At 12, McMahon met his father — Vincent J. McMahon, a professional wrestling promoter who ran Capitol Wrestling Corp. in the Northeast — for the first time.

Spending summers with Vince Sr., McMahon immediately fell in love with wrestling, but his father tried to dissuade him, telling him to get a government job where he could get a pension.

After graduating from East Carolina University with a degree in business, McMahon took on a series of mind-numbing but sensible jobs, selling adding machines, cups and ice cream cones.

In 1966, at 21, he married Linda Edwards; she was 17. Three years later, he convinced his father to let him come work for him.

When the younger McMahon entered the business, the wrestling universe was composed of small, regional organizations. The fight stayed on the mat. For decades, the various organizations didn’t poach talent or encroach on another promoter’s territory.

McMahon changed all that.

In 1979 the company was renamed World Wrestling Federation (from World Wide Wrestling Federation). McMahon then quickly set about shaping the WWF to align with his grandiose ambitions.

In 1980, he and his wife founded Titan Sports. He was chairman and she was co-chief executive.

Two years later, he bought the WWF for $1 million from his ailing father, who died in 1984.

McMahon systematically gobbled up smaller wrestling organizations and siphoned off talent.

‘Most people only categorize Vince as good or evil. But he’s both’

— David Meltzer, a wrestling historian

According to Abraham Riesman’s biography of McMahon, one of the events that helped cement his reputation for unscrupulous dealings happened in 1984 when he snapped up promoter Stu Hart’s Stampede Wrestling in Canada. The Hart family claimed they were never properly paid. However, fearing their son Bret would lose his wrestling job with the WWF, they remained silent.

In 1997 McMahon went one step further. Bret Hart was leaving for a WWF rival and had signed a contract specifying how his character would be written out during a championship match at the Survivor Series pay-per-view event. However, McMahon changed the outcome without informing Hart, according to Riesman’s book. The referee signaled that Hart had submitted to his on- and offscreen archrival Shawn Michaels when he hadn’t, and he lost the world title. To this day the wrestling world refers to this incident as the “Montreal Screwjob.”

A spokesperson for TKO said that McMahon declined to comment about Hart and the “Montreal Screwjob.”

“Most people only categorize Vince as good or evil. But he’s both,” said David Meltzer, a wrestling historian and the editor and publisher of Wrestling Observer Newsletter.

By the time McMahon bought the Ted Turner-founded World Championship Wrestling for $2.5 million in 2001, after years of battling for ratings supremacy, the WWF was a national juggernaut and largely the only game in town. (The company changed its name to World Wrestling Entertainment in 2002 after losing a lawsuit initiated by the World Wildlife Fund over the WWF trademark.)

McMahon ushered in the era of pay-per-view events, turning sizzle to spectacle.

In 1985 he introduced WrestleMania with an inaugural pay-per-view event at Madison Square Garden under the tagline: “The Greatest Wrestling Event of All Time!” It had nine matches, Muhammad Ali was a referee, then-Yankees manager Billy Martin was ring announcer, and Liberace served as timekeeper. More than 1 million viewers tuned in.

It was during this period that McMahon cultivated relationships with cable networks, securing lucrative exclusive contracts. Today, WWE’s broadcast rights drive 80% of its revenue. In 2018, the WWE signed five-year media rights deals with NBCUniversal, which airs “Raw” on Mondays, and Fox Corp., which carries “SmackDown” on Fridays, worth more than $1 billion each.

Soon, a New York real estate developer named Donald Trump became a WWE fixture. He and McMahon became friends. Trump hosted WrestleMania extravaganzas at his hotels and made numerous appearances at matches. In 2013, Trump was inducted in the WWE’s Hall of Fame.

McMahon blended his corporate duties with onscreen roles. First as a broadcaster in the 1970s into the mid-1990s and then as a colorful, villainous in-ring performer, beginning in the late 1990s, a raucous period known as the “Attitude Era.”

By the time WWE went public on the New York Stock Exchange in 1999, McMahon had become the company’s undisputed engine and its face.

There have been some stumbles along the way. Notably, the XFL, a wrestling-inspired alternative to the NFL in 2001 that lasted a single season (it was resurrected years later under different owners, including Dwayne Johnson).

“Don’t get me wrong — I hate failing,” McMahon once said. “But I’m not afraid to take chances and fall on my ass, because if I live through it, I’ll be better off, and I’ll win.”

Those who have worked with McMahon portray him as a fascinating but confounding figure. A tireless workaholic, McMahon, they say, is fearsome, impulsive, a perfectionist and a bully. He can be demoralizing one minute, then a benevolent father figure the next. Most declined to be named out of fear of retaliation.

One former WWE writer and producer recalled what someone told him when he asked what it was like to work with McMahon: ‘“What, Vince? It depends on the day. There’s like 14 different ones,’ and that’s certainly true.”

McMahon could also exhibit a softer side.

“Vince has done a lot of good things,” said Inzitari, the former wrestler. “Whether you were a past or present wrestler, if you needed help with drugs, if you needed to go to rehab, he’d pay for it.”

Although McMahon started and ran the company with his wife, Linda, she has not been involved for years. In 2009, she stepped down as CEO but retained minority ownership in the WWE. In 2017, President Trump named her as head of the Small Business Administration. She resigned two years later, becoming chairwoman of America First Action, a pro-Trump super PAC.

The McMahons’ children, Shane and Stephanie, are both professional wrestlers and have held various positions with the company in the ring and the corporate suites.

Stephanie, who was chief brand officer, seemed primed to take over for her father. Last year, she was named co-CEO and chairwoman alongside Nick Khan after McMahon announced his “retirement,” but she exited when he returned.

For the last 41 years McMahon has famously micromanaged everything from crafting storylines and characters to shuffling executives. Until recently, he continued to go on the road, frequently flying on the black-and-red branded private corporate jet.

“His DNA is on effectively everything that comes out of that factory,” said Court Bauer, a former WWE writer.

Bauer recalled a time when a wrestler was uneasy about doing a move. Despite his age, McMahon went in and said, “‘OK, if you don’t feel good about it, let me show you how comfortable I am doing it.’ And he’ll do this crazy thing to show how much he believes in it.”

Even McMahon acknowledges that he can be cutthroat.

“The Chairman has built his empire ruthlessly and efficiently, dispatching all who stand in the way,” states the official bio for Mr. McMahon, his onscreen alter ego, drawn from his real-life reputation.

Bauer founded Major League Wrestling in 2002. Last year, the New Rochelle, N.Y.-based wrestling promotion filed an antitrust lawsuit against the WWE in federal court, alleging “predatory and exclusionary conduct and abuse of its market power.”

According to the complaint, a 2021 deal with Tubi was terminated when Stephanie McMahon pressured Fox, which owns Tubi and broadcasts “SmackDown,” saying it could “lose WWE business or preferred content if Tubi did not acquiesce to WWE’s demand.”

WWE denied the claims in its filing. The case is pending.

As McMahon muscled his way to wrestling’s top spot, he confronted a string of controversies, lawsuits and scandals.

In the early 1990s the widely reported “Ring Boy” scandal exploded in the press, involving allegations made by underage crew members of sexual abuse and exploitation by high-ranking WWF associates of McMahon’s.

During an appearance on “Larry King Live” in 1992, McMahon denied any knowledge of the alleged incidents.

In 1993, as news of the “Ring Boy” scandal splashed across the tabloids, McMahon was indicted by the Department of Justice on suspicion of illegal activity relating to steroids — and acquitted at trial.

“I’m elated. Just like in wrestling, in the end the good guys always win,” he said.

Dr. George Zahorian, the WWF’s ringside physician, was earlier convicted of illegally supplying anabolic steroids to wrestlers and sentenced to three years in prison.

In 1992, Rita Chatterton, the company’s first female referee, said during an appearance on “The Geraldo Rivera Show” that McMahon raped her in 1986.

This January, just days after McMahon touted his comeback and began pursuing a sale of WWE, he agreed to a multimillion-dollar settlement with Chatterton, according to a report in the Wall Street Journal.

Former wrestler Inzitari told The Times he found Chatterton crying, leaning against the ring apron.

“I asked her what was the matter, and she said that at a meeting with Vince, ‘I got into his limo.’ I went, ‘Oh, no,’ and then she told me her story.”

After staying silent for years, Inzitari said he decided to speak out because “it was the right and moral thing to do.”

McMahon has denied the allegations; his lawyer told the Journal that he settled in order to avoid litigation.

Chatterton’s lawyer did not respond to a request for comment.

In 1999, McMahon and the WWF made headlines once again, when wrestler Owen Hart (Bret’s brother) fell nearly 70 feet to his death in a stunt that went wrong during a live pay-per-view event in Kansas City, Mo. McMahon made the decision to continue airing the event.

The Hart family sued for wrongful death, claiming the stunt was poorly planned and the equipment faulty.

The WWF eventually settled with the family for $18 million, ending a bitter legal fight during which Hart’s widow said the company tried to move the case from Kansas to Connecticut, where the company is based.

In ‘Ringmaster,’ Josie Riesman uncovers the Vince McMahon behind the mean facade of WWE. She talks about his reinventions and how he inspired Trump.

“They put profit over the well-being of my husband, Owen,” Martha Hart told The Times. “I doubt much has changed. The WWE has a dark, enduring history.”

The company declined to comment on Hart’s claim.

This April, Britney Abrahams, a former WWE writer, sued the company in New York federal court.

Abrahams, who said she is one of the WWE’s few Black writers, alleges that the company subjected her to racial discrimination, harassment and wrongfully terminated her. She contends that she regularly opposed racist storylines, one of which included a pitch in which a white male wrestler hunted a Black male one “for fun.”

A spokesperson for TKO declined to comment on the suit.

Through it all, McMahon emerged unscathed.

“Once he survived the ‘90s steroid trial and then had his huge business success starting in 1998, he probably figured nothing would be worse,” said Meltzer, the wrestling journalist.

But in June 2022, McMahon’s invincibility appeared to crack.

The Wall Street Journal reported that McMahon had paid millions in secret settlements to multiple women over claims of sexual misconduct — none of which had been disclosed to the company.

A board investigation found that McMahon made at least $14.6 million in payments between 2006 and 2022 for “alleged misconduct,” according to regulatory filings.

The settlements were made to women, including WWE employees, who alleged that McMahon initiated unwanted sexual contact and coerced women into performing sexual acts on him; in one case a woman claimed that McMahon sent her unsolicited nude photos of himself, the Journal reported.

A person familiar with the board’s investigation confirmed that the company had investigated the allegations, but declined to elaborate.

The individuals who discussed the board’s internal investigation declined to be named as they were not authorized to speak publicly.

The Securities and Exchange Commission and the Department of Justice launched investigations into the matter. Pressured by the board, McMahon agreed to temporarily step down, pending the outcome of its inquiry, and Stephanie McMahon was appointed interim CEO.

“He said, ‘OK, do whatever you guys need to do. I’m not going to stand in your way.’ Of course, when the board said, ‘Well, you know, we think you need to step down,’ he wasn’t happy about it, but he did it,” said one individual close to the board.

During a phone call with the board, McMahon told the committee that “the allegations of unwanted sexual advances were false” and that “all of the relationships were consensual,” said another person close to the board.

McMahon explained to the board that he entered into settlements because “he was protecting the company against potential litigation.”

In November, the board’s special committee concluded its investigation. It found that in addition to the settlements, McMahon made two additional payments totaling $5 million in 2007 and 2009. They were unrelated to the misconduct allegations but were also not recorded in the company’s financial statements, according to regulatory filings.

Ties to Donald Trump

The $5 million represented contributions the WWE made to the Donald J. Trump Foundation, the Journal first reported.

According to the foundation’s tax filings, the WWE made payments of $4 million in 2007 and $1 million in 2009 to the Trump Foundation, which was dissolved by court order in 2018 after the New York attorney general found that it had illegally used charitable funds for political purposes.

The board determined that while McMahon personally made all of the payments, they should have been recorded as WWE expenses because McMahon was a principal shareholder, and they benefited the company.

McMahon was asked to commit to paying for any costs associated with the investigation. As of August, he had reimbursed the company about $17.4 million, regulatory filings show.

McMahon soon came to regret his decision to walk away.

In December he wrote two letters to the board and included in regulatory filings, viewed by The Times, informing them of his intention to return as executive chairman and that he planned to explore a “review of strategic alternatives,” meaning a sale of the company. McMahon was WWE’s majority owner with controlling voting power.

The board disagreed, saying in a letter that his return “would not be prudent” amid ongoing government investigations.

But McMahon overrode the board’s unanimous vote opposing his return by leveraging his majority voting power. He removed three directors and elected himself and two former co-presidents to replace them; McMahon was also voted in as executive chairman.

“He’s the kind of person who expects loyalty,” said someone close to one of the ousted directors, adding that McMahon viewed its investigation as an act of disloyalty, even though the board was doing its job.

Two other board members, Ignace Lahoud and Man Jit Singh, resigned immediately.

Lahoud found the explosion of allegations disconcerting and did not believe McMahon’s return was judicious.

“It wasn’t aligned with my way of seeing what governance is,” he said, adding, “There was a misalignment with what my values are.”

Under his new two-year contract, McMahon would receive annual compensation valued at $7.6 million, use of the corporate jet and ownership of his intellectual property and life story, SEC filings show.

If the company was sold, McMahon would receive a minimum lump sum cash payment of $11 million. As majority shareholder, his equity payout would be worth billions more.

The deal with Endeavor came about quickly. McMahon considered potential suitors including Liberty Media, which owns the Atlanta Braves, SiriusXM and Formula 1 Racing as well as Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund.

In the spring, Emanuel and Mark Shapiro, Endeavor’s president and chief operating officer, made a pilgrimage to WWE’s headquarters in Stamford, Conn. They finalized the deal within weeks in the conference suites at SoFi Stadium during WrestleMania.

Under terms of the deal, Endeavor owns 51%, while WWE has 49%. Endeavor’s WME and management company IMG have represented WWE for more than two decades. UFC President Dana White takes on the role as UFC’s chief executive officer.

“This is a rare opportunity to create a global live sports and entertainment pureplay built for where the industry is headed,” Emanuel said in a statement.

Endeavor is betting on the power of live events and the belief that WWE programming is the last great hope in the fading world of appointment TV.

“I think that the way Ari probably looked at it was, when he took over UFC, he was able to unlock a substantial amount of additional profitability, especially on the sponsorship and branding side,” said Brandon Ross, an analyst at LightShed Partners.

The WWE acquisition was the latest in a string of massive deals fueling uber-agent Emanuel’s ambitious quest to build the media company of the future.

In 2009, Endeavor acquired the William Morris Agency; rebranded as WME, the company, already dominant in television, became a significant player in books, music and movies.

In 2016, Endeavor snapped up a majority stake in the UFC for $4 billion and purchased the entire company in 2021 — the same year it became the first talent agency owner to go public.

But the merger with WWE carries risks. The WWE is seeking to expand its business in the U.S. and internationally just as its ratings have slid. Ratings for “Raw” and “SmackDown” are down 31% since 2018, when the company signed its mammoth media deals that are set to expire at the end of 2024, according to LightShed Partners. However, ratings for both shows are up this year over last, with “SmackDown” the number one program on TV in the 18-49 demographic and “Raw” the top-rated scripted show on cable, according to WWE.

On Thursday, TKO announced that “SmackDown” was moving from Fox to USA Network in a five-year deal valued at over $1.4 billion with NBCUniversal, according to CNBC. The same day, WWE laid off about 10 wrestling superstars and talent, including Dolph Ziggler.

A week earlier, up to 100 staffers at the WWE’s Stamford headquarters were let go, part of cost-cutting efforts to shed $50 million following the merger.

The company has faced criticism that it hasn’t produced an iconic wrestler in years while putting out sclerotic, tired storylines.

New and reinvigorated wrestling rivals have entered the ring, including the National Wrestling Alliance and All Elite Wrestling, founded by Tony Khan, son of billionaire Shahid Khan, owner of the Jacksonville Jaguars and Fulham FC, in 2019.

Perhaps the biggest question remains McMahon and his legacy.

Both the nature and the scope of the ongoing government investigations are still unclear.

The inquiry could be “much broader than the one company and its one majority shareholder,” said attorney Jacob Frenkel, chair of Dickinson Wright’s Government Investigations & Securities Enforcement Practice Group and a former senior counsel in the SEC’s Division of Enforcement.

In an August SEC filing, WWE reported that it had “received voluntary and compulsory legal demands” from various agencies, “concerning the investigation and related subject matters.”

Representatives of the SEC and the U.S. Attorney for the District of Connecticut, where WWE is headquartered, declined to comment.

Depending on the potential findings, McMahon could face criminal and/or civil liabilities that could prevent him from serving as an officer or director of a public company, as well as a clawback of any “ill-gotten gains,” Frenkel said.

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Updates

2:24 p.m. Sept. 22, 2023: This article was updated Friday with news about the TKO stock price, NBC media deal and WWE layoffs.