Ian Karmel regrets writing fat jokes for James Corden

On the Shelf

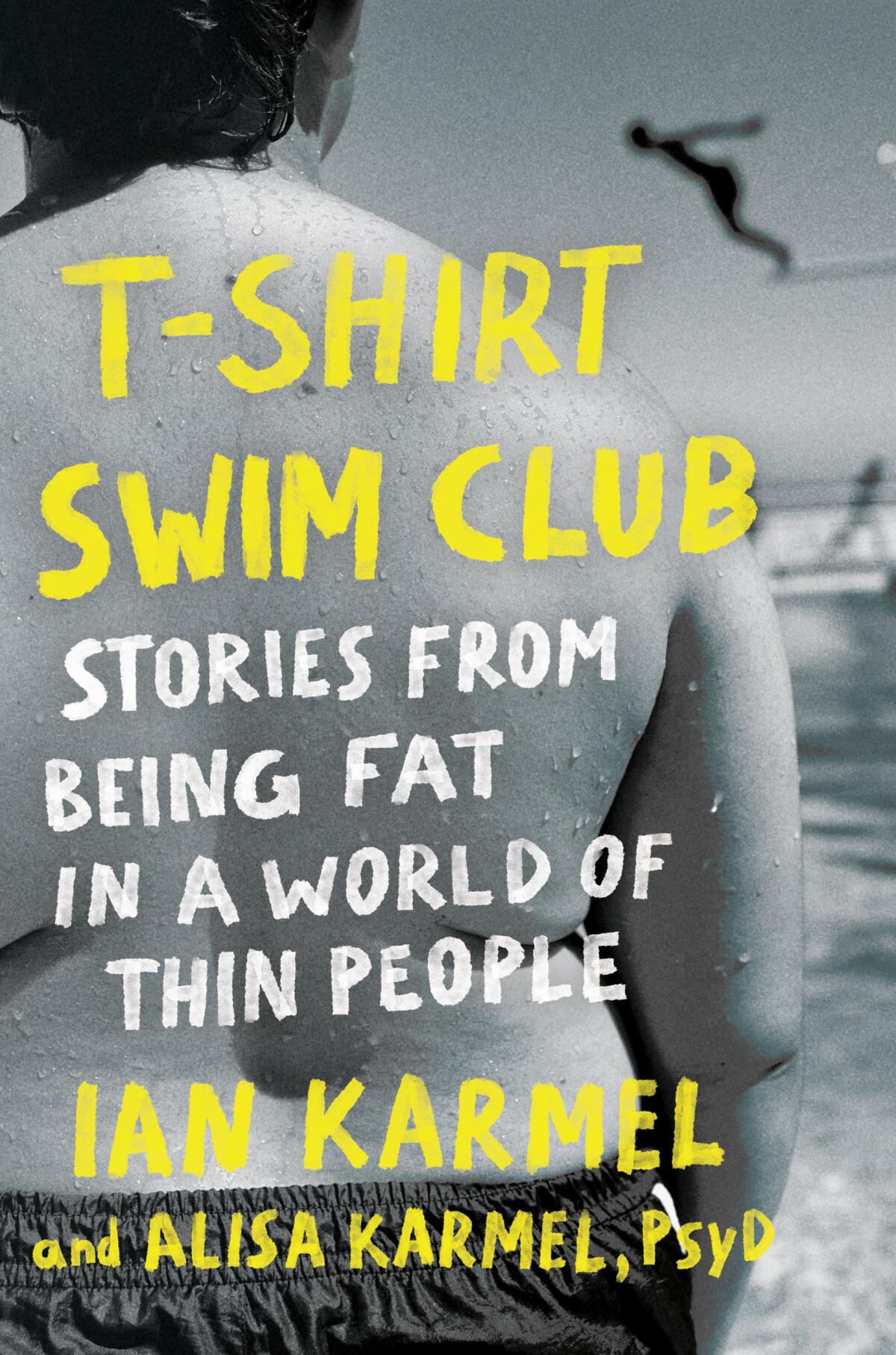

T-Shirt Swim Club

By Ian Karmel

Rodale Books: 304 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

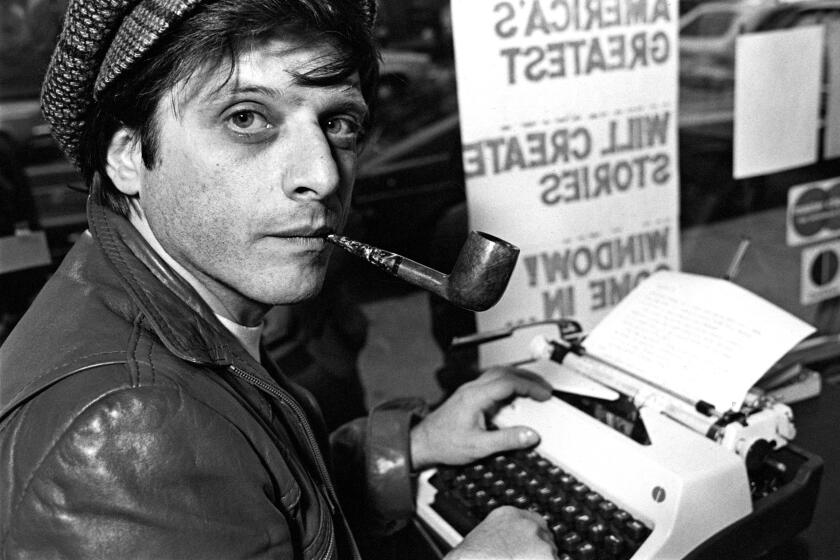

Ian Karmel spent eight years writing for “The Late Late Show With James Corden” and for much of that time, he willingly fed the host a steady diet of fat jokes. Karmel knew whereof he quipped — he’d been fat his whole life and at one point during his “Late Late” tenure topped the scales at 420 pounds.

Looking back from a healthier place — not just because he’s nearly 200 pounds lighter but because he has learned to control all his bingeing and self-soothing habits — Karmel regrets going for those cheap laughs.

That evolution is part of Karmel’s funny but serious memoir, “T-Shirt Swim Club: Stories From Being Fat in a World of Thin People.” It’s an unusual memoir in that the second half of the book is written by his sister Alisa, who also has struggled with weight issues. A clinical psychologist, Alisa writes a chapter corresponding to each one in her brother’s book, examining the “why” behind what he went through.

Ian Karmel recently discussed both the book and his life, explaining that he wanted to make clear he had plenty of great times growing up and throughout his life, despite people mocking him, his own shame and health issues that accompanied his weight. “Fat people are either the punchline or we are this pitiable figure,” he said in a video conversation. “You’re either Fat Bastard from ‘Austin Powers’ or you’re ‘The Whale.’ I wanted to write an emotional, honest story that is hopefully also funny and relatable.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Corden is saying goodbye to his CBS late night show with a starry slate of guests and a primetime special Thursday, but he leaves behind a lopsided legacy.

How important was it for you to write this with your sister and to structure it this way?

If my sister didn’t have a doctorate in clinical psychology, I still would’ve wanted to tell this story, but I don’t think it would’ve been as good or effective. Alisa gives factual information with footnotes and everything — while in my part the only hard facts are things like the year “Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me” came out. So if you have a kid or a friend going through these things or if you are, you can get the facts and the context for the emotions.

You describe how you finally lost weight yet seem wary of being prescriptive.

That was the last thing I wanted to be, having been a fad person my entire life and falling hook, line and sinker for so many diets, I know the sort of desperation that lurks within the hearts of a lot of fat people. I wanted to talk about how I lost weight and got to a healthier place, but it’s more as a thing of hope, not “Here’s how to lose weight in three easy steps.”

The book is quite funny in parts. Were you worried people would think you were deflecting from serious issues?

That reflex, which I developed in grade school, was actually a useful tool in writing this book.

Whenever I felt myself slipping into humor instead of introspection, to deflect a real emotion with a joke, I’d hit pause and ask myself, “What are we trying to not talk about here when we’re making an easy joke?” But sometimes I’d say, “Let’s make that joke and then dive into why that feeling is there in the first place.”

As famed author Harlan Ellison’s collections of speculative fiction are reissued, his longtime home offers a window into his complicated soul.

You write about looking back on regret over the fat jokes you would write for James Corden but how you and he always prioritized the laughs. How hard was that to change?

It’s easy to look back and say, “I wish I hadn’t made those jokes.” Sitting in the writers’ room back then, that version of me would have had a different answer. But honestly, I do regret, and I’m sure James regrets, making some of those jokes.

When you make a fat joke, you’re trying to make the audience feel at ease. Either you’re giving them permission to be bullies or you’re trying to make them feel at ease with your size. The first one is obviously bad and the second hinges on this idea that fat people are some sort of threat or imposition so people need to be made comfortable.

The laughs feel good in the moment, but you look back and you think, “I was doing that to make people who laugh the hardest at fat jokes like me.” And it hurts.

Then we saw Bill Maher fat-shaming, saying, “Just put down the doughnuts and pick up some kale chips” and it was so condescending, this idea of bullying fat people under the guise of wanting to help. The idea is true, but it’s delivered from such a poison tongue and with so much animosity that we reject it — after years of bullying, they want you to pull that one nugget of actual wisdom out.

Then you guys wrote a counterattack for James to deliver on air.

Late-night shows since Jon Stewart have become a beacon of morality and responsibility that comment on the issues of the day. And with Maher, it just made so much sense for us to do it.

After that it wasn’t like an active conversation about not doing fat jokes anymore. But it was more of a good feeling, saying we can use this platform for something positive and it’s going to feel a little hypocritical if we’re still out here doing fat jokes all the time. It felt like that was sort of a hinge moment.

Patrick Nathan’s riveting new novel, ‘The Future Was Color,’ explores basic existential questions ranging from ‘What is life’s purpose?’ to ‘How can there be light and happiness in dark times?’

Do you still see the old you in the mirror?

Yes, but it makes me feel good that I see the same me in the mirror.

Sometimes I post old pictures of myself and I try to do that proudly. It’s like I was that person too, and I don’t consider my weight loss some severance between these two individuals. It’s not “Ian was reborn and started living this healthy life” because there are so many things that I did and so many relationships that I started when I was a bigger person that I treasure and really love. You can’t cut that part of my life out. I’m still that person.

It’s important for me because it reminds me — and yes, this is so cliched that I can feel my eyes rolling out of my own head — that you have a lifelong relationship with your health and there’s not some end goal.

Your obesity was dangerously unhealthy, which you acknowledge yet you also strive to make fat readers know they shouldn’t hate themselves or feel shame about their weight.

There’s so much shame from popular culture, from society, from people around us, even good but misguided people, that I drove my head into the sand just to get away from having my feelings hurt over and over again. And then people often self-soothe with food. For me it turned from food to also drinking, drugs and chasing affirmation through sex. So I want to alleviate that shame in the readers through empathy and relating to them.

You can’t completely break yourself off from that instinct of self-soothing with food even when you do the work and the therapy. But living in Los Angeles, where you make a reference to meditation in every conversation, you learn that it’s not about eliminating intrusive thoughts, it’s about acknowledging them and sending them on their way. That’s what you try doing with food cravings too.

All these people who made you feel bad, all these forces and society that make you feel bad, ultimately you are still the person at the bottom of that pit that needs, hopefully with help, to crawl out of it. You are the person who will die for everyone else’s sins if you don’t take it seriously.

If I could boil these things down, it’s this: It’s not your fault, but it is your responsibility.