Elaine May wasn’t involved with her biography. That didn’t stop this author from telling the comedy icon’s complex story

On the Shelf

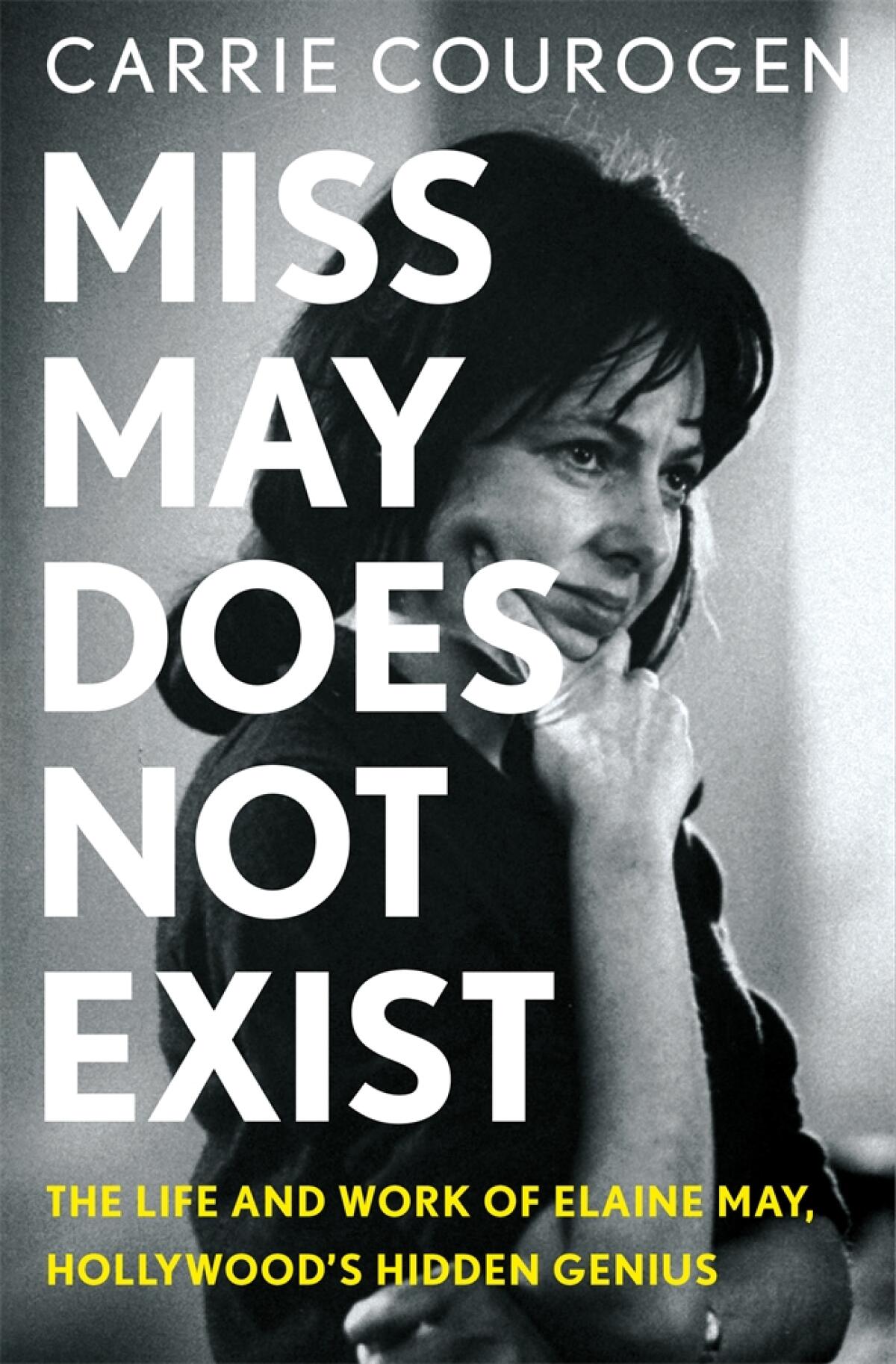

Miss May Does Not Exist

By Carrie Courogen

St. Martin’s Press: 400 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores

Elaine May is one of the key architects of American comedy; an alumna of the influential Kennedy-era underground scene in Chicago that gave us the O.G. “Saturday Night Live” cast and film director Mike Nichols. Tina Fey and Jimmy Fallon have name-checked May as a comedy hero. And yet, despite seven decades as a filmmaker, actor and screenwriter whose movies are entrenched in the Hollywood canon, May is that rarity: a film legend who has opted out of public life. We know the work, but not the creator.

The director of the classic 1972 comedy “The Heartbreak Kid,” with writing credits on Warren Beatty’s films “Heaven Can Wait” and “Reds” as well as Nichols’ “Primary Colors” and “The Birdcage,” May has no need to explain herself or her art; you won’t find TCM’s Ben Mankiewicz gently coaxing chirpy anecdotes from May any time soon. She is not, in short, a prime candidate for a full-dress biography, yet somehow Carrie Courogen has pulled it off.

Courogen’s “Miss May Does Not Exist: The Life and Work of Elaine May, Hollywood’s Hidden Genius” is a minor miracle. Despite the big shrug off by her subject, who doesn’t do interviews, Courogen has produced the definitive book about May’s life and career. This, despite getting nothing from her subject save for breadcrumb trails that went cold, leads that dissolved into thin air.

It certainly wasn’t for lack of trying. Courogen, a journalist and visual content director based in New York, reached out countless times to May’s “people,” a small clutch of confidants that keep a tight lid on 92-year-old May’s hermetic world.

“Elaine doesn’t have a publicist or a gatekeeper of any kind,” says Courogen over lunch at Cafe Cluny near her apartment in Manhattan’s West Village. “I had several conversations with her close friend Julian Schlossberg that gave the impression of being helpful, but it turned out to be stories I had heard before. Then he would tell me to circle back in six months. Or that he would help me fact-check stuff I had heard from other people.”

If May’s willful invisibility seems out of character for someone in showbiz, it makes sense within the context of her career, which has toggled between big-budget features and behind-the-scenes work as a script doctor, for which she has consistently refused on-screen credit. “She has kept herself in the shadows as a choice, yet I kept looking around and seeing work that is so clearly indebted to Elaine,” says Courogen. “She’s done so much, yet no one knows much about her at all.”

We do know this much: Without May, there is no Nichols, or at least the Oscar winner who became a Hollywood titan. The two met in Chicago in the late ‘50s, where Nichols was trying to gain purchase as an actor. May excoriated Nichols for his performance in a local production of August Strindberg’s “Miss Julie” (according to Courogen’s book, Nichols remembers May “breathing hostilely” during his performance). After a cooling-off period, the two bumped into each other again and found, to their surprise and delight, that they shared a love of verbal sparring via lacerating, relentless wit. The two paired up as Nichols and May, and it changed comedy forever.

‘Seinfeld’ star Michael Richards reflects on his infamous racist tirade in his memoir, ‘Entrances and Exits.’ Yes, he is sorry. And he accepts the descent into purgatory that followed.

“There are people who simply belong together, and Elaine and Mike were two such people,” says Courogen, whose book traces the pair’s ongoing working relationship, which lasted until Nichols’ death in 2014. “They really trusted each other. Mike always said, ‘I can only improvise with her.’ He knew that she always made him better.”

As a standup comedy act, Nichols and May erased boundaries between traditional gender roles. The “setup-punch” paradigm was eliminated; so too was the unwritten comedy law that paired the mansplainer with the clueless female foil. Rather, it was the thrust-and-parry of the pair, their gently barbed, whipsmart badinage, that made Nichols and May so revolutionary, their routines about sexual politics and social mores riding a knife’s edge.

Nichols and May became stars with national TV appearances and a series of bestselling comedy albums. After their split in 1961, both took full advantage of their celebrity currency to pursue careers as filmmakers. But while the ambitious Nichols was adept at gaming the Hollywood labyrinth, dutifully learning his craft and winning an Oscar for his second film, “The Graduate,” May took a radically different tack. Having been reared in the experimental, freeform theater of Chicago’s Compass Players, May wanted to transfer that unpredictable energy to her film sets. May went over budget on her first film, “A New Leaf,” alienating her crew with endless takes and delays as a result of her rudimentary knowledge of film production (Courogen points out that she mistook a light for a camera). But she elicited great performances from her cast, which included a cranky Walter Matthau. When Paramount recut the film, May tried to get it shelved. But “A New Leaf” was finally released and it made money. Almost despite herself, May had directed a hit.

May’s next film, “The Heartbreak Kid,” adapted from a Neil Simon hit and co-starring her daughter Jeannie Berlin, is a beautifully calibrated and funny social critique wrapped in concertina wire. The squirmy comedy of manners introduced May’s discovery, Charles Grodin, to the world. May makes the story her own, losing Simon’s penchant for shtick and leaning on her actors for emotional ballast. “I think it’s her best film,” says Courogen, “which is interesting because she didn’t write it, yet she put her stamp on it.”

Still, May continued to disregard the rule that penalizes those directors who take budgets lightly. 1976’s “Mikey and Nicky,” a bleak gangster buddy film, was plagued by cost overruns and a lumpy plot. “It’s the one film of Elaine’s I never return to,” says Courogen. “Ishtar,” a 1987 comedy about a pair of hapless aging songwriters (Dustin Hoffman and Beatty) who chase their fortunes in the Middle East and wind up embroiled in a political scandal, was one of the conspicuous flops of the era, a very expensive shaggy dog story. May went whole hog with the budget. When the director approached songwriter Paul Williams to write a couple of songs for the film, the studio flew him to the Morocco set, where he slept in the desert to soak up the atmosphere. May repeatedly rejected Williams’ ideas; all told, Williams wrote more than 50 songs for the film, only a few of which saw daylight.

“Ishtar” has stubbornly clung to its reputation as a very expensive disaster; the title became a talk-show punchline and May never directed another Hollywood film. But did May deserve all the blame? As Courogen points out, it was Beatty who refused to learn his lines, which resulted in massive production delays. May was a chronic over-shooter, but so was Beatty, who burned 2.5 million-plus feet of film for his historical 1981 epic, “Reds,” which May co-wrote. As Courogen points out, male directors fail upward all the time; female directors have no such margin of error to work with.

“I think the first act of ‘Ishtar’ is perfection,” says Courogen. “It’s the one Elaine film I watch the most. She gets great performances out of her actors. That’s what she cared about, not whether they were losing light in the desert. Her attitude was, ‘It’s not my money, I don’t give a s—.’ That didn’t exactly endear her to the studios.”

It is May’s unerring instinct for locating the emotional core of a story, of “breaking the spine” of problematic scripts, that has endeared her to directors desperate to resuscitate dead writing on the page. May refused to accept formal credit for her rewrites, and thus became that rarest of creatives, gleefully anonymous in a town where grown adults would kill for their name above the title. “She wanted to have some control over how she was being perceived,” says Courogen. “If the movie worked, it would go around town that Elaine saved it. If it didn’t work, she wouldn’t be the fall guy.”

Courogen has no expectations that May will somehow emerge from her apartment on the Upper West Side to shake her hand for a job well done. It doesn’t matter: She has produced a fascinating, three-dimensional portrait of a brilliant, complicated artist who has somehow stuck to her guns and gotten away with it.