Is Madonna a game-changing feminist or capitalist come-on? A biography hashes it out

- Share via

Review

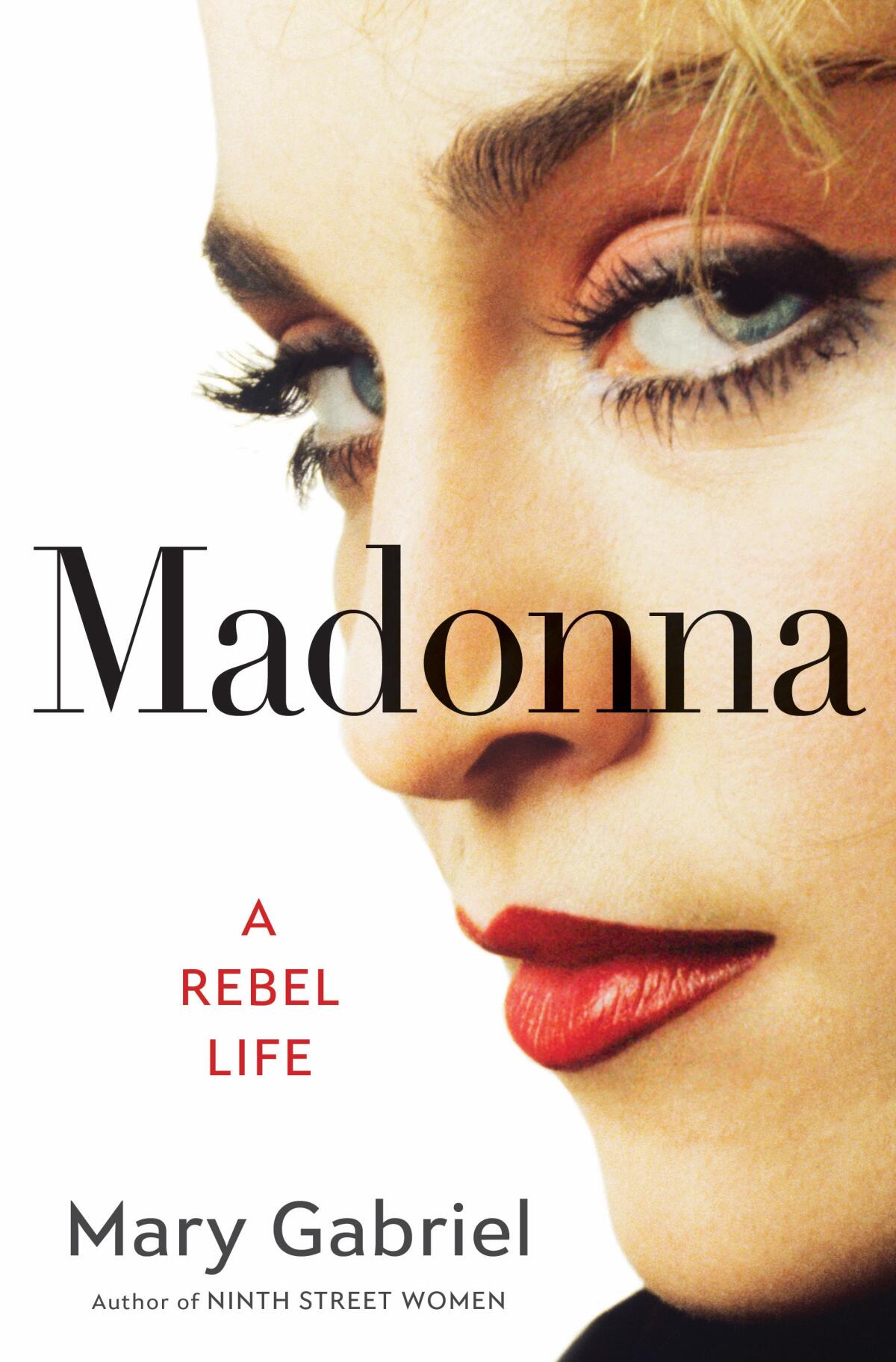

Madonna: A Rebel Life

By Mary Gabriel

Little, Brown: 880 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Mary Gabriel’s new biography of Madonna is a bookshelf hog. Clocking in at more than 700 pages, not counting a bibliography that could be its own stand-alone volume, “Madonna: A Rebel Life” uses ballast as a statement of intent, a way of telling the reader before they crack the spine that this is a subject worthy of the kind of assiduous attention given any other great 20th century artist. That is absolutely right, though the result is an alternately fascinating and lumpy account of a singular career.

Gabriel, a Pulitzer Prize finalist and a former Reuters reporter, has left no stone unturned, but if Bob Dylan can have multiple warehouses of books written about him, surely we should have a full-dress account of Madonna Louise Ciccone, a generational talent who challenged our notions of sexuality and gender while she was reeling off a brilliant series of singles over a 40-year run. Still, this very large book is just a bit too much.

Madonna wants fans, and critics, to see ‘how cute I am now,’ weeks after her appearance at the 2023 Grammys drew backlash.

As tends to be the case with music bios, the first third of the book, when Gabriel deftly lays out the modest roots of Madonna’s global ascendancy, is the most compelling tranche. Raised in a middle-class Catholic household in Pontiac, Mich., by a strict father — a scenario not dissimilar to her 1986 music video for “Papa Don’t Preach” — she chafes against religion and tilts to the noise of rebellion.

“Madonna lived a double life,” writes Gabriel. “One intensely sad and angry and insecure, the other a ballsy bravado performance for public consumption.” For her eighth-grade talent show, she covered her clothes in fluorescent-green paint and danced to The Who’s “Baba O’Riley” as her disgusted father averted his camera.

Her insecurity melts away as she finds her footing as a dancer. According to Gabriel, under the tutelage of her Ann Arbor instructor Christopher Flynn, “the disparate pieces that would become Madonna the artist came together: sex, dance, and musical performance.” But Michigan is too small for Madonna’s global pursuits, and she makes the obligatory pilgrimage to New York in the late ‘70s — armed with an acceptance letter from Alvin Ailey’s dance troupe and a small amount of money earned cleaning houses, among other odd jobs.

New York was, of course, the right place at the right time. Madonna befriends Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, Fab Five Freddy and Jenny Holzer — artists who circumvent the traditional gallery route and take their art straight to the people. This is how Madonna will do it, as well. Having written a few songs with her Michigan boyfriend Stephen Bray, she makes a beeline for taste-making club Danceteria and persuades its star DJ Mark Kamins to spin her song “Everybody.”

The floor clogs up with dancers, Madonna among them. Kamins contacts Sire’s A&R rep Michael Rosenblatt, who sends the demo tape straight to Lenox Hill Hospital, where Sire’s chairman Seymour Stein is recovering from a heart infection. “As penicillin dripped into my heart, I lay there and listened,” Stein recalled years later. He summons Madonna to his hospital bed, and a record contract is consummated.

From there, Madonna’s bullet train jumps the fast track. She masters the nascent art of music video and dominates MTV with instant classics: “Borderline,” “Crazy for You,” “Burning Up.” There is the arresting bustier-and-tulle performance of “Like A Virgin” at the 1984 MTV Music Video Awards, where millions of viewers are convinced they have caught a glimpse of Madonna en deshabille.

She had become a star and a symbol — but of what, exactly? Parsing Madonna’s cultural impact has long been a kind of parlor game among humans who think about such things (there are many of us, I assure you). Has she wielded her sexuality like a self-made cudgel? Or is it merely a consumer come-on? Gabriel rightly comes down on the side of the angels: For the author, Madonna has worked hard to stake a claim to her own kind of feminism, a performer who regards sex as a source of strength rather than exploitative shame.

“In mocking the social covenant that traditionally codified a woman’s status as lesser,” Gabriel writes, “she declared liberation not in the language of feminist politics but in the language of sex.”

With much more serious choices pending for Americans at the polls in just a couple of days, the side-taking game surrounding Madonna’s collapsed marriage is trivial at best.

After winning over New York, Madonna in short order takes over the world, while also shaping the world’s view of itself. When the AIDS epidemic tears through New York’s gay community, taking with it many of her closest friends, Madonna is the first pop star of her stature to speak up about the necessity for research and a cure. Today, that might be called “getting out in front” of a social issue, but Madonna was a crucial beacon of AIDS awareness at a time when the president of the United States had yet to acknowledge the existence of the disease.

With Madonna, though, it all comes back to forward motion. In the 1990s she continues to find new terrain to explore alongside producers William Orbit and Diplo while constantly revising the rules of music video’s vocabulary, in the process becoming the most influential visual artist of her time.

As the years progress and Madonna acquires the icon mantle, Gabriel is intent on enumerating every recording session, video shoot and world tour in great detail, making this book a slog at times. After 1990, when Madonna has become a fixture of our collective consciousness, the stakes aren’t quite as high as they once were. There is also the matter of critical analysis, which is mostly offered second-hand from other sources. There is a lot to like about and learn from “Madonna: A Rebel Life”; the depth of your “Madge” worship will determine whether you will go the distance with it.

Marc Weingarten is the author of “Thirsty: William Mulholland, California Water, and The Real Chinatown.”