What the sale of a major American book publisher means for authors, the industry — and you

It seemed to many in book publishing like good news last October when the Department of Justice successfully sued to block Penguin Random House (PRH) from acquiring Simon & Schuster. PRH is the largest publisher in the United States and S & S is third. Together they might have controlled more than half the industry. Only three other publishers — HarperCollins, Hachette and Macmillan — control the bulk of the rest. Such consolidation has long worried literary types who fear it leads to the privileging of profit over culture. But the alternative in this case might prove worse. On Monday, Paramount sold Simon & Schuster to KKR, a private equity firm.

Simon & Schuster’s role in the book world

Simon & Schuster is a 99-year-old house. Founded by two Jewish bookmen, Richard Simon and Max Schuster, it was among a wave of new firms established in the first half of the 20th century by Jewish bookmen, including Knopf, Random House and Viking. But whereas these other houses were literary ventures, S & S was more commercial from the start. While Random House profited from the scandal of James Joyce’s “Ulysses,” S & S grew on the back of crossword puzzle books.

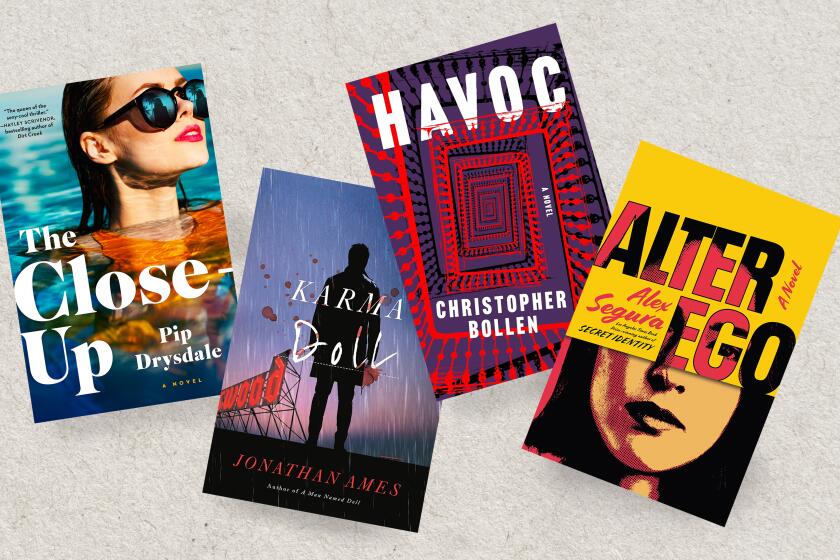

Paramount acquired Simon & Schuster in 1975, leading to vast growth through acquisitions, with a focus on educational and professional publishing. By the 21st century, Simon & Schuster had become a behemoth, one of the Big Five, inevitably containing multitudes. Today its imprints include commercial lines such as Atria (Vince Flynn, Colleen Hoover, Jodi Picoult, Brad Thor) and the venerable Scribner (Stephen King, Kiese Laymon, Jesmyn Ward) whose backlist features F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway.

Paramount announced Monday that it’s selling the storied publisher for $1.62 billion, months after a sale to Penguin Random House was blocked by a federal judge.

What is KKR?

Kohlberg Kravis Roberts is an investment company founded in 1976. Henry Kravis and George R. Roberts continue to hold positions as executive co-chairmen. They pioneered leveraged buyouts in the 1980s, culminating in one of the largest in history when they bought out RJR Nabisco in 1989. As first documented in the investigative blockbuster “Barbarians at the Gate,” the firm established an early record of buying companies, loading them up with debt, then squeezing them for profit — maybe most famously with the slow death of Toys R Us. More recently, KKR acquired hundreds of facilities for people with disabilities, which, under the new ownership, led to conditions in which residents were “consigned to live in squalor, denied basic medical care, or all but abandoned,” according to Polk-winning reportage from Buzzfeed.

Its reputation has grown more complicated over time, even as it’s made some incursions into publishing. KKR is enormous, with more than $500 billion in assets. Simon & Schuster, purchased for $1.62 billion, will account for less than one half of 1%. Still, KKR co-CEO Scott Nuttall told the the Wall Street Journal that “the firm puts new growth opportunities through a screen. ‘Can we do it in a way that is special? Can we get to the top three in the world?’”

KKR has some publishing connections. Co-CEO Joseph Bae is married to the respected novelist Janice Y.K. Lee — though she publishes with PRH. More notably, Richard Sarnoff, chair of KKR’s media group, worked in publishing from the 1980s until 2011. He helped the German conglomerate Bertelsmann acquire Random House in 1998, after which he became an increasingly influential figure in the industry, an early advocate of audio and new media who also pushed publishing toward increasing financialization through further acquisitions and investments in venture capital.

Biden administration receives a clear victory, with the judge ruling the blockbuster merger would diminish competition in book publishing.

One benefit touted by Simon & Schuster as well as KKR on Monday is its habit of offering equity to employees of its companies. Such a program will now be established at S & S. This worked out well for the company’s recent publishing asset, RBMedia, the world’s largest audiobook publisher. Acquired in 2018, RBMedia was sold last month in a deal that, according to KKR’s statements to the New York Times, earned employees payouts of up to two times their annual salaries.

What does the sale mean for the industry?

It is, in one sense, the continuation of an old story. The corporatization of publishing began in the 1960s. Times Mirror acquired the esteemed mass-market paperback house New American Library in 1960 and hired McKinsey consultants to rationalize its operations, leading to increasing control for the business office and an exodus of editorial talent that included luminaries such as E. L. Doctorow and André Schiffrin. Few acquisitions or mergers have been as dramatic since, though all nudged publishing toward prioritizing financial growth. The big difference this week is that for decades media companies have tended to acquire publishing houses: Bertelsmann, CBS, Hachette, Holtzbrinck, News Corp, Paramount. Not so much private equity.

The consequences for the industry have been complex: One could write an entire book just covering fiction. Writers and editors have developed creative strategies for meeting the needs of growth-oriented parent companies while doing good work. The question is whether a private equity firm runs things differently.

Jonathan Karp has been named Simon & Schuster’s new CEO. He replaces Carolyn Reidy, who died two weeks ago from a heart attack at age 71.

Initial commentary from top figures at KKR and Simon & Schuster have focused on growth. “I believe that they are committed to helping us grow and become even greater than we already are,” S & S CEO Jonathan Karp told the L.A. Times in an interview Monday, calling the purchase “very good news for readers and publishers everywhere.” He touted KKR’s track record of audiobook production — one avenue of planned growth — as well its proposal to offer employees equity that could result in “a life-impacting amount of wealth.” In the short term, both sides say business at Simon & Schuster will carry on as usual. Of course, they have motivations for saying so.

What does this mean for books and readers?

What happens next is unpredictable. Will Simon & Schuster end up like Toys R Us or RBMedia? We know that KKR will aggressively pursue growth. It is likely less concerned with accommodating the niceties and vagaries of publishing than the other parent companies of the Big Five. One the one hand, this might mean Simon & Schuster becomes flush with cash, enabling its staff to explore compelling new projects (so long as they facilitate growth). On the other, it could mean radical transitions at the publisher, including layoffs and changing terms for contracts with authors. Colleen Hoover, a mega-bestseller, is probably safer than Kiese Laymon, a beloved critical darling whose books have little impact on S & S’s bottom line.

Ebook sales are higher due to coronavirus, but bookstores are shutting down. In the end, Amazon wins.

Truth be told, the average reader is unlikely to notice much of a change. Not because there won’t be change, but because whatever change comes will merely be the acceleration of a half-century trend of increased conglomeration and shareholder-driven thinking — a process going back to Paramount’s acquisition in the 1970s of a company it was more recently trying to sell for years.

Sinykin is an assistant professor of English at Emory University and author of the forthcoming book, “Big Fiction: How Conglomeration Changed Book Publishing and American Literature.”