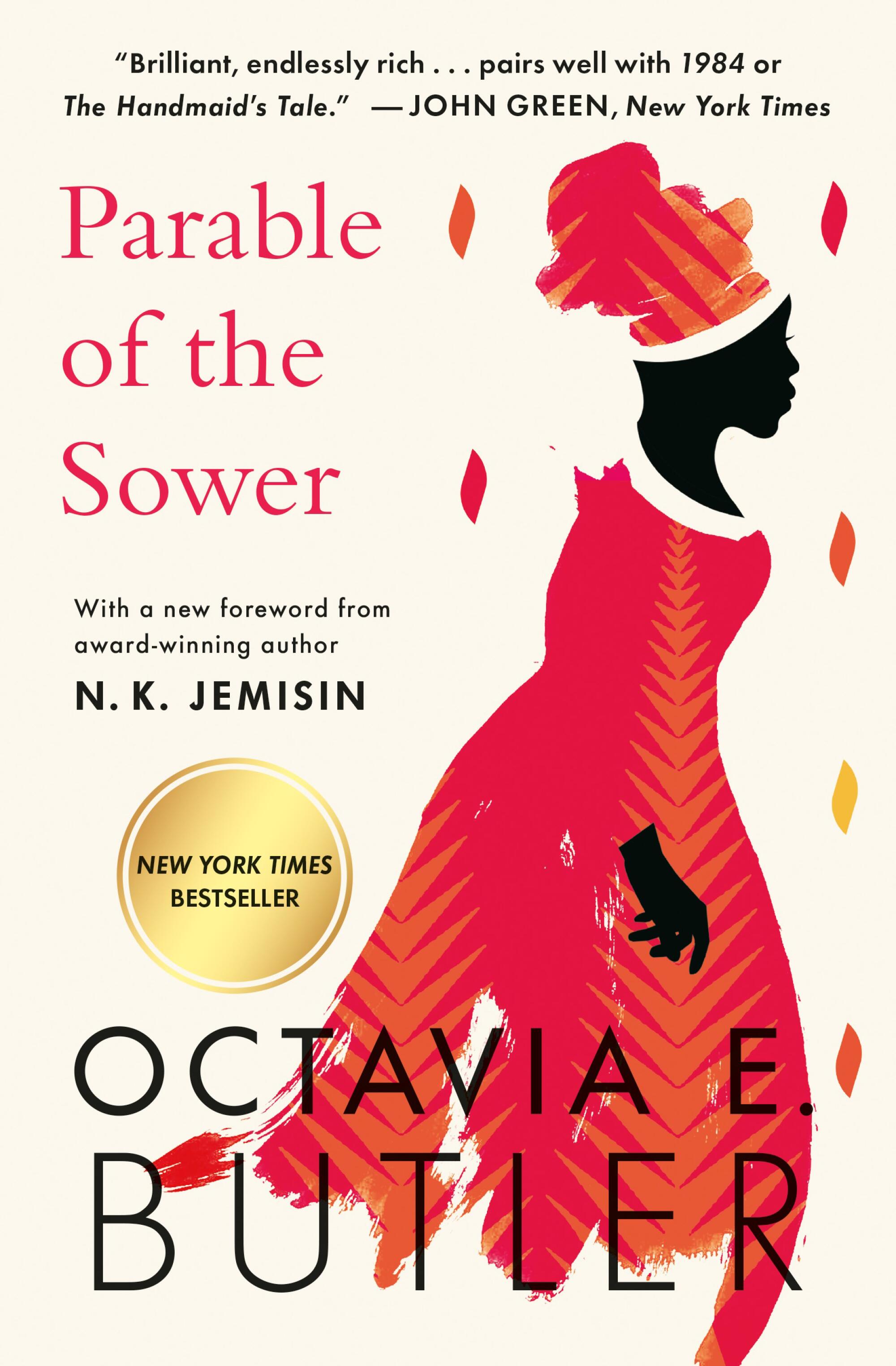

Octavia E. Butler published “Parable of the Sower” in 1993, when she was 46 and I was 12. I came to the book later than you might expect for an L.A. writer with a postapocalyptic novel of my own, but when I finally did, I was stunned. Here was a tale set in the world I knew in my darkest hours: the ravaged, water-starved, earthquake-ridden, fire-eaten Southern California that plays in my dreams, a vision of my dear, troubled homeland that will keep me up at night if I let it. This book — it was already in my bloodstream.

L.A.s 13 most essential works of speculative fiction, from Octavia Butler, Philip K. Dick, Aldous Huxley, Salvador Plascencia and many more.

The story, which takes place in the now-uncomfortably-close 2024, is a string of diary entries written by a Black teenager named Lauren Olamina. She resides with her family in the fictional city of Robledo, 20 miles from the center of Los Angeles. Beyond the walls of her gated neighborhood roam violent thieves, feral dogs, illiterate water peddlers and addicts whose drug of choice makes them hungry for arson. When those walls are breached, most of the inhabitants killed for their property and possessions, Lauren flees. She disguises herself as a boy and, armed with the gun her preacher father taught her to shoot, joins the hordes of other migrants heading north on the 101 — on foot.

This is a future at once vivid and brutal, and it’ll scare you down to your scalp. How did Butler do it?

Perhaps it’s that the author — noted genius and inspiration for a thousand internet memes, with a middle school named after her and a new bookstore too — began as a daughter of Pasadena. She grew up in Southern California, as did I, and this place of sunshine and danger, with its attendant anxieties, must have imprinted on her, as it did on me.

But there’s more to it. A writer like Butler becomes iconic not only by reflecting our world and interrogating it but also by articulating our most profound truths. As I see it, Butler’s gift is naming vulnerability, exploring its burden and value.

In “Parable of the Sower,” Lauren is a “sharer,” meaning she suffers from a condition called “hyperempathy syndrome.” She can feel the pain and pleasure of others, and in this future there isn’t much pleasure to be had. For most of her life, Lauren kept her sharer status a secret because, as she tells it, “Being the most vulnerable person I know is damned sure not something I want to boast about.” As the story progresses, however, and she encounters the wider world, including her first sight of the Pacific Ocean, Lauren divulges her syndrome, her gift, to others.

She also tentatively shares the religion she is beginning to shape. For Lauren is also a prophet. She names her religion Earthseed, and in her journal entries we witness Lauren trying to make sense of it, to comprehend a system of meaning that she believes is already fully formed and simply waiting for her to bring it forth. Lauren isn’t the sloganeering prophet I’m used to; she is fumbling toward truth. Her vulnerability, no matter how burdensome, signifies hope. It is exhilarating and profound, and it’s what animates this dystopian novel.

Author and Ultimate Bookshelf contributing editor David Kipen digs for treasure in a bibliography of L.A. fiction — and celebrates the “ghost novels.”

For me, “Parable of the Sower” is a call to be daring in my fiction and to reside in feeling, to show characters revealing their most fragile selves — and at a high cost. What could be more dramatic? The question resonated as I wrote my forthcoming novel, “Time’s Mouth.” The book, like Butler’s, also takes place in California, and it’s also about a young woman with an exceptional way of experiencing the world — in this case, an ability to time travel to one’s own past. Butler’s novel led the way with its own wild premise, and it also taught me that a sensitive heroine must put herself at risk, must grapple to comprehend her gift, if her story is to feel consequential.

This is only one way my work is indebted to Butler, a writer who offered a terrifying vision of my hometown and showed a way forward — in fiction (and in the craft of fiction) if not in fact. Those who conjure frightening futures aren’t in the business of fortune-telling, only in the sharing of cautionary tales. I don’t want to find myself in the California of Butler’s imagination, as much as it might thrill, as easy as it is to picture. Thank goodness I can read it.

Lepucki is the author of the novels “California” and the forthcoming “Time’s Mouth.”