More than a ‘nameless maid’: A memoirist’s manifesto on Latinx colorism

On the Shelf

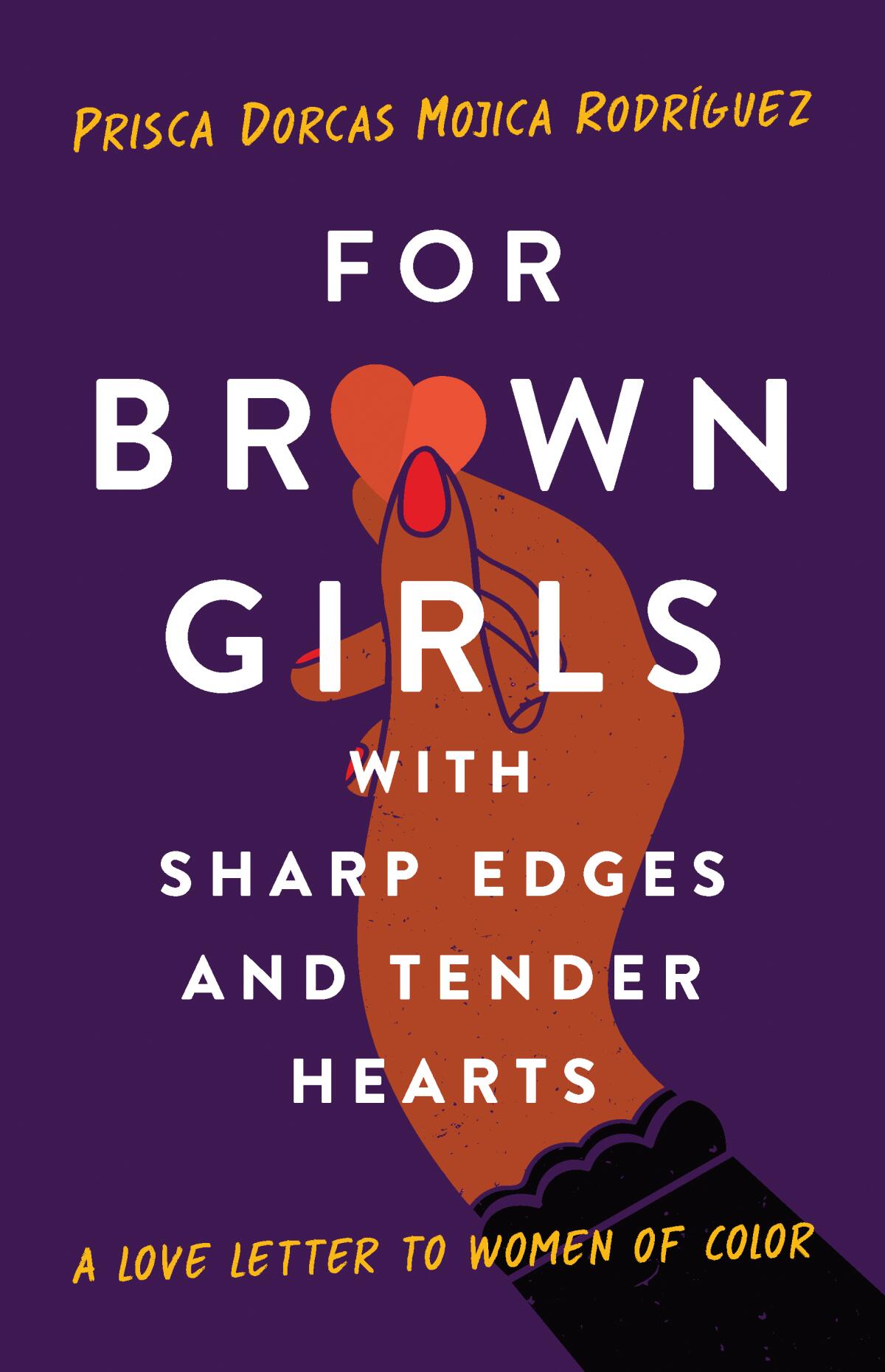

For Brown Girls With Sharp Edges and Tender Hearts

By Prisca Dorcas Mojica Rodríguez

Seal: 272 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Growing up in Miami in a family of immigrants from Nicaragua, Prisca Dorcas Mojica Rodríguez sought role models in Spanish-language films and in telecasts on Univision and Telemundo. But none of the Latina anchors and lead actors looked like her. They looked European, light-skinned. The times she did see herself, it was in what she calls “the nameless maids” on the periphery.

These damaging cues weren’t confined to mass entertainment. A high school counselor tried to dissuade her from taking more advanced-placement classes; her graduate school’s English-proficient writing center rejected her because English was her second language.

Against those odds, Mojica Rodríguez obtained a master’s in divinity, launched a successful online conversation platform called Latina Rebels and became a prolific writer — in English. Now, she has written a self-described love letter to women of color.

Mojica Rodríguez’s electrifying debut, “For Brown Girls With Sharp Edges and Tender Hearts,” channels mesmeric prose to heal the wounds of white supremacy. A theologian, she deliberately uses the rhythm and cadence of a Pentecostal sermon.

“I cannot undo the fact that my skin glows from all this sunlight,” she writes. “Like magic, my skin turns sunrays into nutrients, into vitamin D.” She recalls painful moments on the road to self-acceptance, such as her mother telling her to stay out of the sun: “Te estás poniendo negra” (You’re turning Black).

“We somehow have allowed ourselves not only to internalize racism, but to become Brown white supremacists,” she observes in the book, emphasizing that she’s not criticizing her mother but rather the widespread “normalization of the supremacy of whiteness.”

Out with “L.A. Weather,” her third novel, María Amparo Escandón talks about fleeing L.A.’s wildfires, dreading the climate and loving her adopted city.

“For Brown Girls” is more than a celebration of brownness at a vital moment, as political race-baiting continues to fuel hate crimes against people of color. It is also a manual for tapping into brown girls’ power to fight the ways white supremacy excludes and erases them.

“I hope it provides almost like a map as to what to anticipate and how to maneuver those spaces,” Mojica Rodríguez told me. “A playbook for how to survive.”

Reckoning not only with racism and colorism but also toxic masculinity, she calls on all Latinas to embrace the parts of ourselves we have long been taught to bury in shame. She spoke with The Times over the phone, in a conversation edited for clarity and length, about her book, a long-overdue corrective that should be required reading in many schools.

Since the Black Lives Matter protests in response to George Floyd’s murder, there has been an increase in Latinx Americans reckoning with our colorism and anti-Blackness. How did that conversation shape your book?

I was very aware that I’m writing about colorism as a non-Black person of color. I was trying to hold the tension of: “I have experienced colorism; I also have benefited from colorism.” I do hope that moving forward, it creates a better way for us to have those conversations. Latinxs who are lighter skinned have been generally more resistant to having those conversations. I kept rewriting that chapter [on colorism], trying to figure out how to be gentle to our people but also push us to be better. And I hope it’s the beginning of us being more transparent.

How are Latinos in positions of power failing our diverse communities?

The main failure is our lack of awareness of colorism. The lightest of us are usually the ones who end up with the opportunities first. The failure has been in not acknowledging that. And we are taught to overvalue whiteness even when there’s no white people around. The more we’re willing to be honest about the ways we’ve been harmed instead of trying to approximate ourselves to whiteness, the more we can do for our communities. I’m not prescriptive in ways a lot of [popular] anti-racism texts are. They center white people, and this book doesn’t do that at all. In unveiling all my scars in a way, I hope people are open to listening instead of rushing to defend whiteness as we’ve been taught to do.

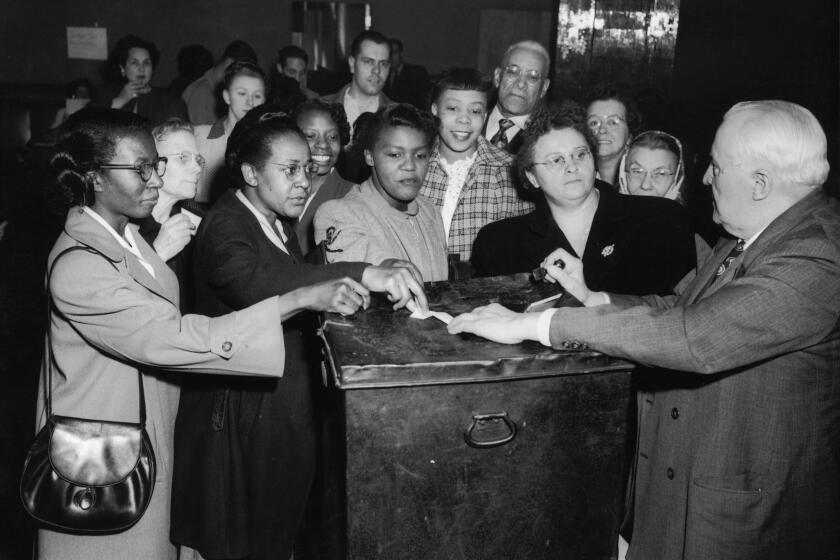

Remember the names Fannie Lou Hamer, Constance Baker Motley and Mary McLeod Bethune. Vice President Kamala Harris does, as does historian Martha S. Jones.

What was the most challenging part of writing this book?

My imposter syndrome. I got over that by going on Amazon Books and seeing what these mediocre white men have been writing for years. I was like, “I got this. This is going to be OK.” I got past the hump of doubt by looking at others who had no doubt.

I did that too when writing my biography about Trump advisor Stephen Miller, and it helped a lot. Speaking of Trump, what are your thoughts on the increase in Latino support for Trump between 2016 and 2020?

My dad’s a Trump supporter and my brother is too. They’re visibly brown men who look indigenous and will go to a [resort at an Indian] reservation in Miami and be asked for drinks. It’s the delusion in certain bubbles like Miami, where you’re surrounded by people who might look like you — the delusion that you are just as white as other white people. It’s a very confused state of being. I think I experienced that too — all these microaggressions in white Latinx spaces — but I was unable to see it until I was around white-white people, and I was like, “Oh, this is bad.”

Why was it important for you to explore your father’s machismo in this book?

Machismo is seen as different than sexism. I’ve heard Latinas who specifically date white men: “White men are sexist but they’re at least not machistas.” I think it’s a missed analysis of oppression and the ways it has functioned in some very dramatic ways. [Many brown] men have been taught very linear ways of existing because of toxic masculinity, and some haven’t been able to shake that off because of oppression.

You write that brown girls’ fire comes from their mothers. I knew immediately what you meant. But can you elaborate on it?

[My mom] got married young because she had to, and she doesn’t have a college degree. I’ve always been very aware that my mom’s a feminist even if she doesn’t say it and even if she rebukes it. I think there’s fire in that, there’s power in that. She won’t even let me act like I might know a little more than her. She’s always fighting to have a place. She’s always fighting to exist. She’s always fighting to not be thought of as less than. Even as the walls were crumbling, she was constantly working to keep the walls up for herself and for everyone, and I think that’s what feminism is.

And yet she was the wife of a macho pastor, right?

She told him [off] at one point. He would bring people over all the time, and she’d have to serve everyone and be the doting wife. Then they’d leave, and she’d have to clean up and [stay up] late and he’d do nothing. So one day she made a clear declaration: “I don’t want to host anyone ever.” He brought people against her will, and she didn’t help at all, which meant her losing respect from congregants. But she was pataleando [Spanish for kicking or rebelling]. She was fighting always for some autonomy, and people need to understand that fire.

Jean Guerrero, author of “Hatemonger,” talks about the making of Stephen Miller, who helped make Trump president, then remade the U.S. immigration system.