The ‘Super Emmys’ flopped 50 years ago. But that shouldn’t minimize this historic ‘Mary Tyler Moore Show’ win

In “Inside the Episode,” writers and directors reflect on the making of their Emmy-winning episodes.

Is Hulu’s “The Bear” a comedy? Was HBO’s “Succession” a drama? And should they be judged as equals?

If this were 1974, TV fans could have seen this knock-down, grudge match play out in real time.

For that year’s Primetime Emmy Awards, the TV Academy introduced “Super Emmy” categories. Meant to be a tongue-in-cheek battle of the genres, 14 already announced Emmy winners (including actors, writers and directors) competed for the “Super Emmy” during the telecast, going head-to-head with their genre counterparts (best comedy director battled best drama director, etc.). To pull this off in a reasonable time frame for a live production, the Academy revealed the winners of the traditional categories ahead of time and then asked members to re-vote for the “Super Emmy” winners, which would be unveiled at the ceremony.

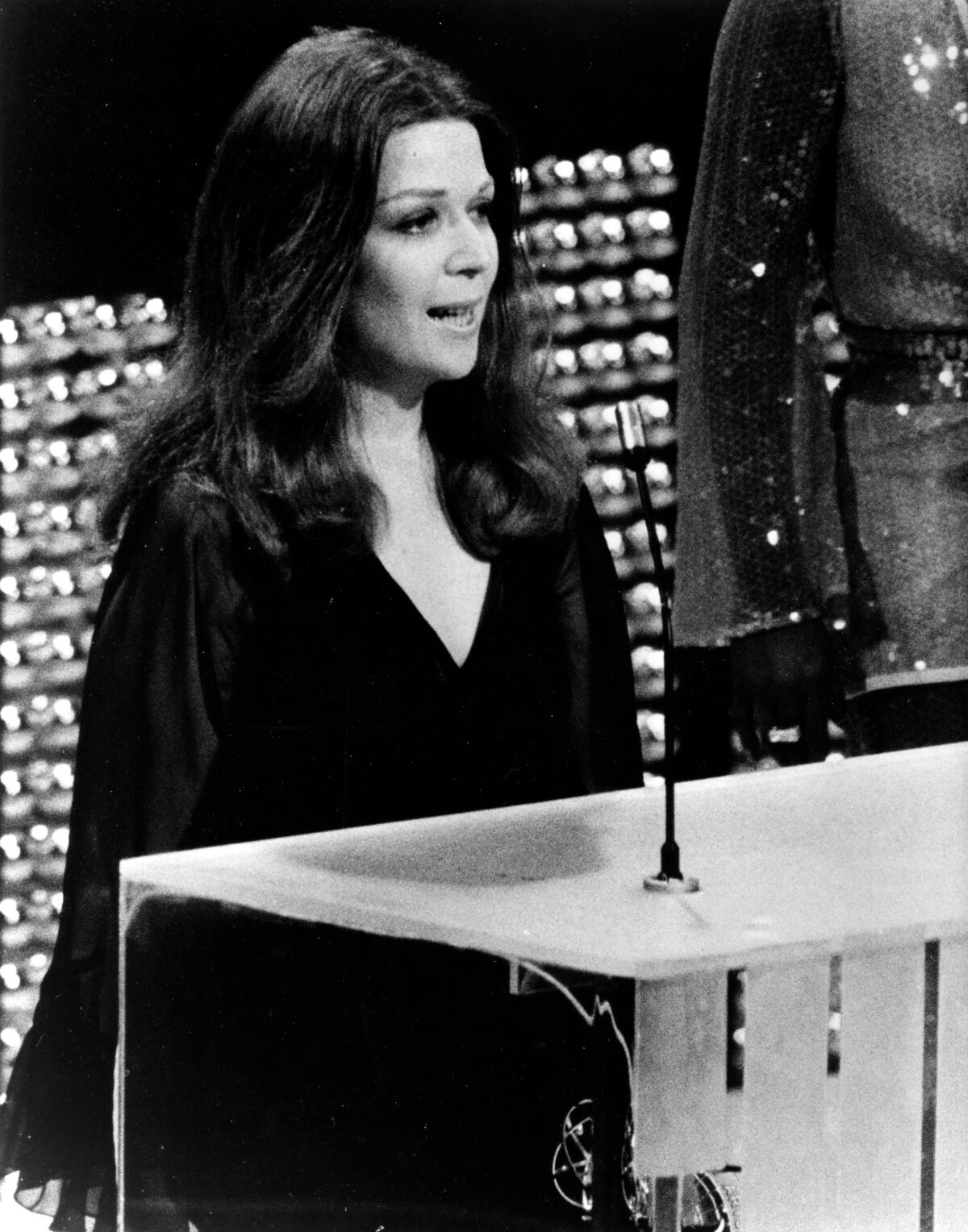

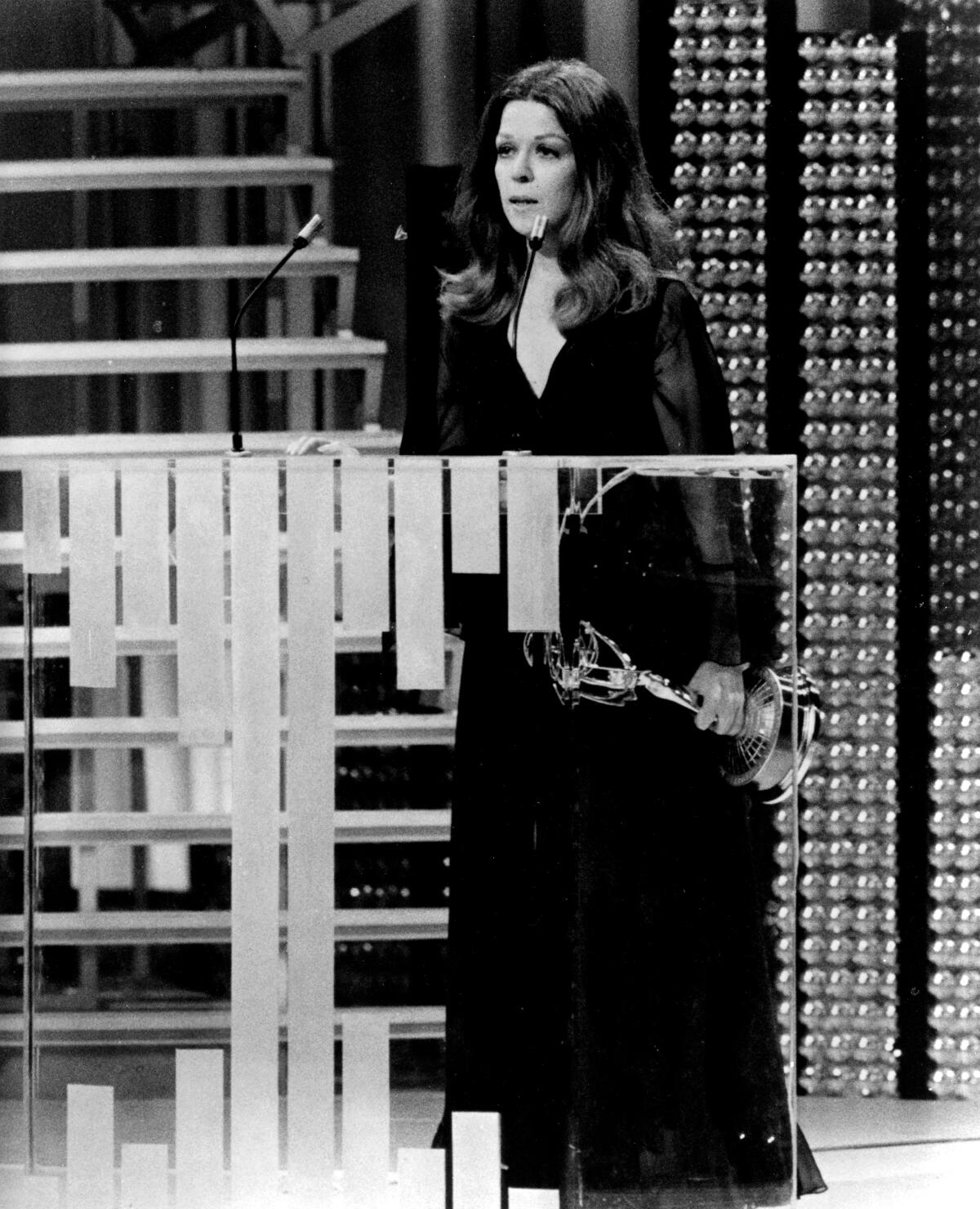

Ironically, some of the biggest opponents of the “Super Emmys” were also its winners, such as actor of the year recipient Alan Alda (“M*A*S*H”) and actress of the year recipient Mary Tyler Moore (“The Mary Tyler Moore Show”). Each used their acceptance speech to ridicule the category.

The “Super Emmys” did not get a second-season renewal.

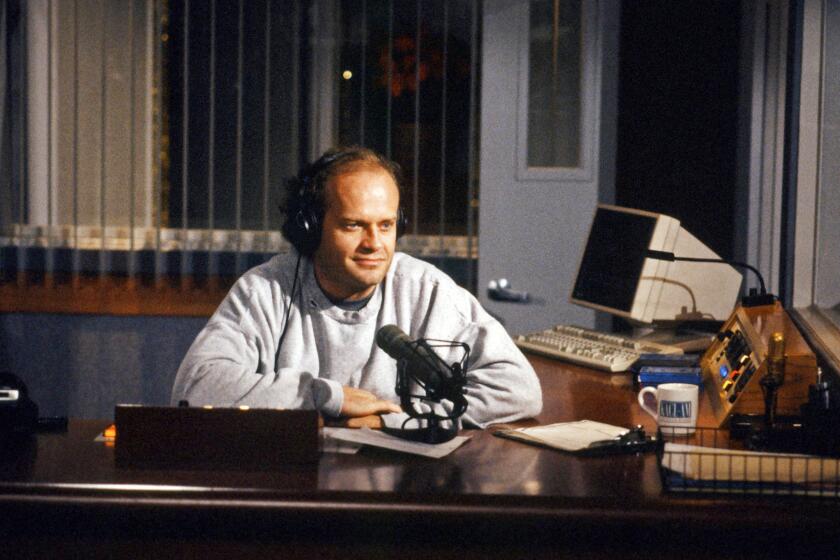

James Burrows discusses directing the original ‘Frasier’ pilot, including why Peri Gilpin replaced Lisa Kudrow as Roz.

“It was so stupid … it took all the magic away,” says writer Treva Silverman, whose script for “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” “beat” Joanna Lee’s for “The Waltons” to anoint her writer of the year.

This bizarreness shouldn’t minimize the work that Silverman’s episode did, both in front of and behind the camera. The main category win made her the first woman to receive the comedy writing Emmy solo, without sharing a byline with a male partner.

And its plot is still prescient.

Titled “The Lou and Edie Story,” the Season 4 episode centers on Ed Asner’s lovable curmudgeon Lou Grant, whose wife leaves him midlife to start her own journey, a subject, he divulges in the episode, that they talked about in couples therapy.

“He was a typical ’50s male — humiliated that he should even have to express this and it had to be dragged out of him — until [the end of the episode when she leaves and] he says, ‘I’m warning you … I’ll take you right back,” Silverman recalls of the couple’s emotional final moments.

It was then, she said, that this buttoned-up, emotion-averse follower of traditional gender roles “entered the 1970s.”

In an interview with The Times that has been edited and condensed for clarity and space, Silverman expounds on developing this landmark episode.

Counseling and therapy weren’t talked about as openly then as they are now. How did you decide on this topic?

This episode aired in 1973 and, eight months before, Roe v. Wade happened. [And] this was something that was informing the whole women’s movement.

I don’t remember how [the idea for marriage therapy] came about. But if there wasn’t that element, it would be hard for him to just discuss that he and Edie were having problems. And also, it added a tension to the first few scenes because it was his not wanting people to know.

In rewatching the episode, I noticed Jay Sandrich’s beautiful direction. When Ed Asner is [talking] to Mary and to Murray [Gavin MacLeod] (about his marital issues early in the episode) and they both lean forward, and [they’re] hoping that something good’s going to come out of it … [Jay] so understands the human condition.

I noticed also that there was a lot of Lou saying [to Mary], “I can’t say this to you. I have to say it to a man.” And, probably, that attitude is why [his wife is] leaving him. Roe v. Wade had passed and everyone’s going to women’s groups and he [still] can’t talk to Mary because Mary’s a woman.

Just as with real-life assassination attempts, to really understand the power of ‘The West Wing’s’ two-part Season 2 premiere, ‘In the Shadow of Two Gunmen,’ requires a look back at the actions before the attack.

Edie (Priscilla Morrill) tells Lou that she’s leaving him because she’s 45 and has been with him since she was 19. She doesn’t know life without him. Was that experience based on someone you knew?

No. In fact, we had never met Edie in the whole series before this. This was the total introduction of her. I based it on a character whom he would have been in love with and they would have had a good marriage until now.

It was “who would this person be?… How would he have picked her and how would she have picked him?” She was a kid [when they met] and he’s funny and he takes over everything, which at that point [in our culture] was a good thing.

Jim [Brooks, “MTM’s” co-creator] had an insightful thing about casting. This one actress read absolutely gorgeously. But she was very diminutive. He said no because Ed would look intimidating next to her. When Priscilla came in, it was perfect. Strong-looking, not a little diminutive.

Asner has a couple great monologues in this episode. One is when Edie’s getting ready to leave. He squishes an orange and starts ranting about fruit seeds …

I wanted him to get so ridiculous and off the topic that only his anger was coming through about something that made no sense. I wanted to give him a monologue in which he’s not addressing what’s going on.

Michael Lembeck talks about directing the Emmy-winning ‘Friends’ episode with guest stars Julia Roberts and Brooke Shields, and how Jean-Claude Van Damme and Andre Agassi’s bad behavior complicated the set.

There’s some comic relief when newscaster Ted (Ted Knight), not knowing that Lou and Edie are having problems, jokingly flirts with her. You’ve said before that writing Ted was largely influenced by your mother’s tendency to always say inappropriate things.

My mother was a good person, but her empathy was never fully developed.

It’s hard for me, as a writer, to write somebody I don’t like. And I wanted to like Ted. And it occurred to me that my mother comes up with all of this stuff.

Out of the blue, I had to have a hysterectomy. Before I told my mother, I told one of my sisters whom I knew would be able to comfort me and to whom I could tell the truth about my feelings. So a week after, I thought it’s finally time to tell my mother.

I said, “Mom, I want you to know I’m perfectly fine, everything’s OK and I’m healthy, but I do want to tell you that I had to have a hysterectomy.” And she said, “Well, did you get a second opinion?”

After my dad died, my mother moved down to Florida like all nice Jewish widows. After a couple of seasons there, I asked her what it’s like and if she had friends there. She said, “I have some wonderful friends. I don’t analyze them. They don’t analyze me.”