Latinx Files: My father, former political prisoner, recalls the Chilean coup 50 years later — finally

Periodically, the Latinx Files will feature a guest writer. This week, Martina Ibañez-Baldor, De Los design director, steps in to write about her family’s experience living through the 1973 Chilean coup.

Monday marked the 50th anniversary of the start of the Chilean military coup that forever changed the sociopolitical landscape of the country.

On Sept. 11, 1973, a U.S.-supported rebel military junta led by Augusto Pinochet overthrew the socialist government of democratically elected President Salvador Allende. What followed was a brutal 17-year dictatorship that saw tens of thousands of people dead, disappeared or imprisoned. Hundreds of thousands more were forced to flee.

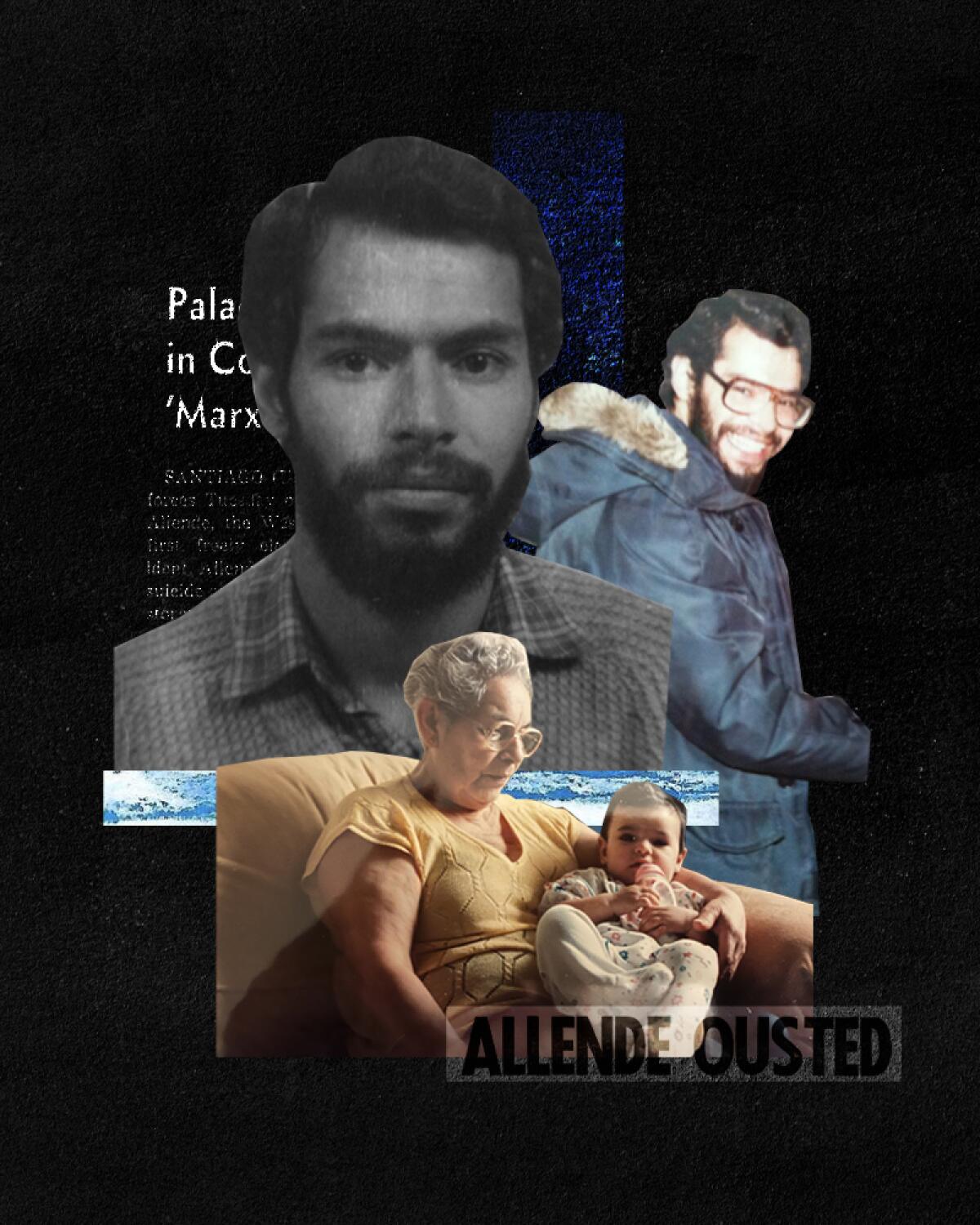

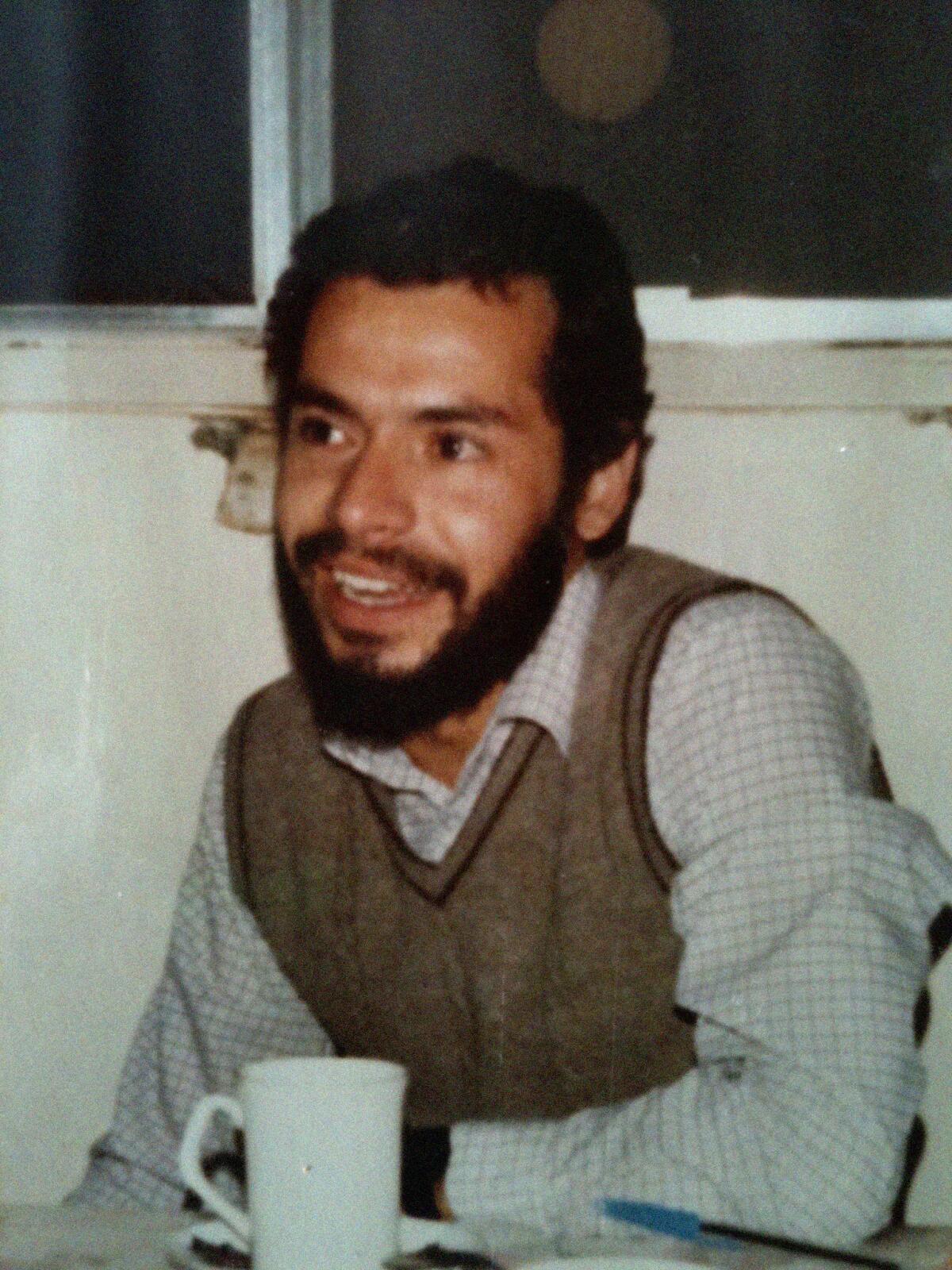

My dad, Javier Ibáñez-Noé, and his older brother, Ralph Ibáñez-Noé, were among them.

The two were born and raised in Valparaiso, Chile, and were arrested by the new regime because they belonged to a political party that supported Allende. My dad was 17 at the time, and was held for a few weeks. My uncle was 25, and his stint as a political prisoner lasted eight months.

“I suppose it’s long enough in the past for these things to be talked about,” my father told me when I asked if I could interview him about his experience. He has always downplayed this period of his life and talks about it very casually, when at all.

I grew up with an Argentine mother very proud of her homeland. She would dress us in the national team jerseys, and took us on several trips to Buenos Aires. My dad is the polar opposite. He’s largely maintained a physical and emotional distance with his country. He rarely went back.

I didn’t learn much about Chile until recently, during a two-month trip I took with my sisters around the country he had left behind. We visited family we had never even heard of before.

One of my newfound family members is my dad’s cousin, Veronica Nuñez. She welcomed us to her home in Quilpué with open arms and showed us where our father grew up, telling us stories about him, my uncle and grandmother that we had never heard.

On Monday, I reached out to my family in Chile via our WhatsApp group chat (they endearingly named it “las gringitas + familia”) to get their thoughts on the anniversary.

“Viene los dolorosos recuerdos de aquella época,” she told me.

Veronica remembers being caught in a shootout on her way to visit her grandmother a few days after the coup. She recalls watching men be executed in the street “and that horrible fear you feel when you think you’re going to be gunned down.”

Veronica and my dad were very close. Attached at the hip, she says. She cried a lot when she found out my dad had been taken prisoner.

My dad minimizes every memory he has of his incarceration, usually rationalizing that things weren’t really that bad.

“I’m pretty sure my mom beat me up worse than they did,” he said.

Of being forced to listen to someone being tortured: “I figured at one point that those must have been recordings that were being played for us to get scared. It was really bad even if it was just recording.”

Of his captors pretending to execute him via firing squad: “I knew what they were doing. So I just kept playing along. I started pretending I was crying.”

My dad tells me he was eventually released because he stuck to his claim of innocence. Veronica says his life was spared because the person in charge of the firing squads couldn’t give the order because my dad reminded him too much of his son. This, of course, is hard to verify.

Other stories that Veronica told me of my dad’s imprisonment, he did not remember. My uncle believes that his younger brother was in shock.

“I just have this recollection that more or less things were OK with me,” my dad said. “But [my brother] thinks it was such a traumatic event that I forgot what happened.”

Soldiers returned to my grandparents’ home the day after my dad was released from the detention center. They were looking to arrest his brother. Because the regime had confiscated my dad’s documents during his last arrest, he couldn’t prove his identity when the armed men became convinced he was his brother and wanted to take him away again.

“My mom just went ballistic and I don’t know how she did it, but she convinced him that I wasn’t my brother,” my dad said. “That was a scary moment.”

He would dismiss rumors he heard about what was happening, believing them to be too outlandish. Many of these were later proved to be true.

He had heard that activist folk singer Victor Jara was tortured and murdered in a Santiago sports complex that was converted into a detention center for 5,000 Allende supporters. This turned out to be true.

He heard a rumor that bodies of the missing were being dropped from airplanes, mid-flight. This really did happen.

He also dismissed the notion of the CIA’s involvement in the military coup.

“It was another shock,” he says. “All these things that I thought were just false rumors, almost all of them turned out to be true. I was trying to remain objective in a sense, not get swept away by the rumor mill. It was shocking and sobering.”

Last month, the State Department with the CIA declassified two 50-year-old documents that showed knowledge of the military coup.

“They contained information that went to President Nixon as a military takeover that he and his top advisor Henry Kissinger had encouraged for three years came to fruition,” the National Security Archive said in a statement.

In 1988, Pinochet was defeated in a presidential plebiscite. He stepped down in 1990. More than 40,000 people had been killed, tortured or imprisoned during his rule. Long before then, my dad, his brother, sister and their parents had immigrated to Saskatchewan, Canada, as refugees.

“My mom was so happy to be in Canada, she didn’t want to think about Chile either,” my dad recalls.

Fifty years later, Veronica feels happy to have democracy in Chile again.

“But we cannot forget the horror,” she cautioned. “And we have to protect that freedom, something that I think too many of us have forgotten.”

For my dad, it still feels like a dream.

“I sometimes had the sensation that Chile was just a dream of mine. It actually didn’t happen. I became so removed, so unconcerned with Chilean reality.

“Of course I knew it was not a dream. But that sensation. That’s one of the reasons why my brother might be correct. I was in shock, and as a consequence I just forgot everything.”

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

We want to hear from you.

The stories and events of the Chilean coup do not end with the Sept. 11 anniversary. Pinochet’s rule lasted 17 years and it affected hundreds of thousands of families. Do you or your family have a memory about the Chilean coup? Share your experience with us.