By the time he died in Bungalow 3 at Chateau Marmont at age 33, John Belushi had been hurtling toward disaster for years, in plain view of friends, hangers-on and industry associates.

Recklessness was baked into Belushi’s persona. He became a breakout star on the original “Saturday Night Live” in the mid-1970s, with roles that included a giant bee and a deranged, gibberish-shouting samurai. A magazine called him “The Most Dangerous Man on TV.”

In “Animal House” he played a lovable, mischief-making slob who guzzled liquor like water, stuffed whole burgers in his mouth and spit mashed potatoes in imitation of a popped zit.

In this series, Christopher Goffard revisits old crimes in Los Angeles and beyond, from the famous to the forgotten, the consequential to the obscure, diving into archives and the memories of those who were there.

“My characters say it’s OK to screw up,” Belushi once said. “Most movies today make people feel inadequate. I don’t do that.”

One “SNL” writer, a sometime companion on his cocaine jags, spoke of Belushi’s “very self-destructive drive, that crazed death-oriented gusto that puts the edge on his performance.”

During the making of “The Blues Brothers,” director John Landis found Belushi with a pile of cocaine and punched him in the face, according to “Wired,” Bob Woodward’s book about the comedian.

After Belushi’s overdose death on March 5, 1982, police learned the names of people who had accompanied him for parts of his final, fatal binge at the Sunset Boulevard hotel, where he had been living for $200 a night. No arrests were announced. There likely would have been no criminal case at all, save for the guile and enterprise of the National Enquirer.

“They wanted people who were willing to run through brick walls to get a story, and we did,” Tony Brenna, who led the Enquirer’s coverage, told The Times in a recent interview. “At the time, you had carte blanche to do whatever it took. It was endless high octane.”

The English-born Brenna is now 91 and living near Seattle. He thrived in mainstream journalism for decades, covering the United Nations for the London Daily Telegraph and the BBC before joining the Enquirer in the mid-1970s, when the tabloid was selling nearly 6 million papers a week. Many who thrived there were British reporters trained in the aggressive checkbook journalism of London’s Fleet Street.

Working for “one of the most scabrous papers in the world” was fun, liberating in its looseness, though it “exacerbated my amoral streak,” Brenna said. His salary was in the six figures — “three times the amount of money the regular press was paying.”

A retired Los Angeles Times copy editor began researching the Black Dahlia murder case in the late 1990s. Arguably the world’s top authority on the mysteries surrounding Elizabeth Short’s death, he believes he knows who killed her.

In his unpublished memoir, “Anything for a Headline: A Reporter’s Life,” Brenna reflects — sometimes with a troubled conscience — about his years as “a ruthless predator … the perfect tabloid operator.”

He was chased out of Memphis for trying to bribe a janitor for Elvis autopsy photos, and chased out of Israel for ambushing Henry Kissinger’s wife at a hotel pool. He was just back from Moscow, where he covered a cardiology conference (an Enquirer staple was “miracle medical cures”), when he got a call that Belushi had been found dead. He arrived at Chateau Marmont in time to see the comedian’s covered body wheeled to the coroner’s van.

He then set out to find Catherine Evelyn Smith, one of the last people to see Belushi alive. At 34, a former roadie, rock band groupie and occasional backup singer, she had clung to the periphery of the entertainment industry for years. She had been the live-in paramour of musician Gordon Lightfoot, who wrote a song about her. She had jet-setted with the Rolling Stones and partied with The Band.

By March 1982, she was living in Los Angeles and dealing heroin to pay for her own habit. Cathy Silverbag, she was called, because she carried drugs in her silver purse. Police briefly detained her after Belushi’s death, found a syringe and spoon in her purse, then released her. She fled to her native Toronto.

Brenna jumped on a plane. With another Enquirer reporter, he prowled Toronto’s seedier precincts. They went from bar to bar, club to club, buying people drinks, handing out cash and leaving word for Smith. After a few days, she showed up at their hotel in a fury — they were spooking her drug connections.

“We offered her $20,000 for her story,” Brenna recalled, but she wanted $40,000. “We spent a decadent week, smoking grass, drinking, hanging out with her. She was hanging on for 40. We couldn’t get 40 for the story.”

Hunkered over a Xerox machine at an ad agency above a flower shop on Melrose Avenue, Daniel Ellsberg began the laborious process of photocopying the smuggled documents that he hoped would end the Vietnam War.

The editors had given instructions about the exact words they wanted extracted from Smith. “The story wasn’t gonna fly unless we got the headline, ‘I killed John Belushi,’” Brenna said. “That’s what the Enquirer was like in those days — they’d come up with a headline before you had the story.”

Desperate for cash, Smith eventually capitulated with a taped account of how she’d injected Belushi with speedballs — a mixture of heroin and cocaine. But she refused the Enquirer demand that she pose with a syringe in front of Belushi’s photo.

“She had a kind of girl-next-door quality about her, but beneath that was a real street person — reckless and out for a good time,” Brenna said. “She was quite fun to be with. Even the Enquirer was shocked by our expenses. We basically partied with her for a week before we got the stuff we wanted to get.”

Brenna liked her but also considered her “a real scumbag,” adding: “Hollywood produces a lot of people like that.”

Along with celebrity gossip, horoscope news and a story about a sperm-bank baby, the cover of the June 29, 1982, issue featured a surly-looking Smith, with the quote “I Killed John Belushi” and the tease, “World Exclusive — Mystery Woman Confesses.”

“I didn’t mean to, but I was responsible for his death,” the story quoted her as saying. “At 3:30 a.m., I shot up John for the last time. He got his coup de grace — which is what he wanted.” Belushi feared needles, so she shot him up, she said, describing herself as “Florence Nightingale with a hypodermic syringe.”

Brenna was hauled before a Los Angeles County grand jury, and the Enquirer was forced to turn over its tapes. In March 1983, a year after Belushi’s death, Smith was indicted on a count of second-degree murder — a charge potentially carrying 15 years to life — and 13 counts of administering cocaine and heroin to the comedian.

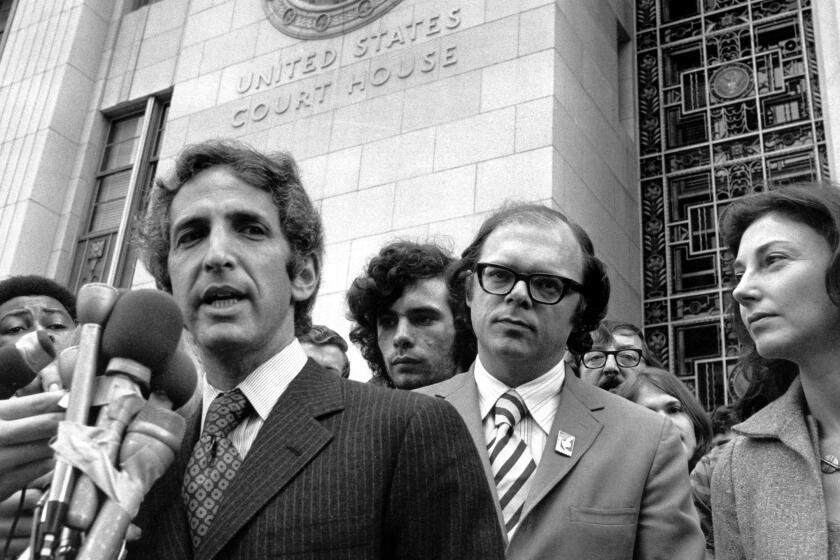

Her attorney, Howard Weitzman, insisted that Belushi had been on “a suicide mission” and that his client was a victim — she had just done what Belushi asked her to do.

“She clearly didn’t intend to murder anybody,” Weitzman told reporters. “In my opinion, the real culpable individuals in all of this are the people who continued to give Mr. Belushi money, knowing where that money was going.”

A judge excluded most of Smith’s taped confession, including the “coup de grace” remark, saying that she had given the statements in “an atmosphere of levity” and that she didn’t necessarily understand what she was saying. But enough was admitted to keep the case alive, and at Smith’s preliminary hearing in September 1985, Belushi’s companions testified that she had injected Belushi multiple times in the days before he died.

Patricia Hearst’s transformation into a fervent member of the SLA was part of a strange saga at the nexus of leftist militancy and American aristocracy, saturation media coverage and youth revolt.

“I felt bad for the woman, because I listened to the audiotapes of the confession,” Elden Fox, who prosecuted the case, told The Times recently. “They wined and dined her. They took her to a very expensive hotel. They fed her lots of alcohol. She was obviously well-lubricated. During the course of their interview with her, you could hear things in the background like, ‘Would you like another drink, Cathy?’”

“How often do you get a case where the person not only provides the drugs but admits to injecting them?” Fox said. “Her defense could have been, ‘I only told [Brenna] that because I needed the money,’ but I don’t think if it went to trial that would make her a very sympathetic defendant.”

Smith agreed to plead no contest to involuntary manslaughter, and Fox thinks she would have received probation if she had not relapsed before her sentencing.

Instead, a probation report noted that she had 54 fresh needle marks, and Superior Court Judge David A. Horowitz scolded her. Yes, Belushi’s “drug-infested life led to his own death,” but she was also culpable, the judge said.

She served half of a three-year prison sentence, got out in 1988 and was deported to Toronto.

“The larger story is, don’t sell your story when you’ve committed a crime. In Cathy’s case, I don’t think she understood that at the time,” Fox said. “Obviously, hindsight is 20-20, but I think the money was too attractive for her. She was not doing well. She didn’t have a consistent source of income.”

In 1998, nearly a decade after leaving prison, Smith appeared at Hollywood High School to give an anti-drug lecture, warning students that addiction leads to “an early grave, an institution, a dumpster.” She denied giving Belushi the fatal speedball and claimed she was misquoted about the “coup de grace.” She was prosecuted, she insisted, because “I was the only one left standing.” She died in 2020 at age 73.

Brenna, who is seeking a publisher for his journalism memoir, said he is proud of having cracked the story, but his feelings about his role in Smith’s fate are more complicated.

“She went in the slammer. It was the only time I’d actually put someone in prison, which I didn’t feel too good about,” he said. “They were all bloody embarrassed to be bringing a prosecution based on a National Enquirer story.”

The tabloid’s circulation is way down from its peak, hobbled by online competition and scandal, and Brenna calls it “a limping wreck of what it once was ... reduced to a miserable husk of itself.”

The criminal trial was fresh in memory when the DMC-12 — equipped with the mysterious “flux capacitor” — served as a time machine in the 1985 hit “Back to the Future,” enshrining it in pop culture.

Shawn Levy, who wrote “The Castle on Sunset: Life, Death, Love, Art, and Scandal at Hollywood’s Chateau Marmont,” said that while the music industry had seen high-profile overdoses, from Jim Morrison to Janis Joplin, Belushi’s death “was kind of the first celebrity OD that touched on Hollywood primarily.”

Film industry executives tried to intercede to stop his drug use, “but he was kind of a volcano, and he was voracious, and nothing was gonna stop him.” In addition, Levy said, “one of the reasons people let him get away with awful behavior is they didn’t want to alienate him and lose him for potential projects.”

At the time of Belushi’s death, Chateau Marmont was a favorite of bohemian New York actors, and its run-down vibe —with mismatched furniture and duct-taped carpet — was part of its charm.

Also, Levy said, it offered privacy from paparazzi and looky-loos. “Your drug dealer didn’t have to go through a lobby. They could come around the back and never be seen. It was really, really private.”

The hotel remains open, with celebrity sightings still common, and cottages can now rent for $1,200 a night. Before the comedian’s overdose, it was a hideout for those in the know.

Afterward, “it’s ‘Chateau Marmont, the hush-hush hotel where John Belushi died,’” Levy said. “That becomes its identity.”