This L.A. suburb says it’s a ‘dumping ground’ for sex offenders. Residents want to stop that

When kindergarten teacher Cynthia Farrow searched for a community where she could raise her family and afford a home with enough space for a few horses, she settled on the sunswept desert town of Littlerock in the Antelope Valley.

Farrow, along with her husband, Gary, and their 10-year-old son and 3-year-old daughter, bought a home in 1996 in the hamlet about 50 miles northeast of Los Angeles.

“We were priced out of so many places except here in the AV,” Farrow said, referring to the Antelope Valley. “It was a dream place, and we found a community here. But, sadly, that attracted others here too.”

The affordability, the low population density and the space between homes and properties — often measured in acres — is also enticing for correctional authorities and courts across the state looking to relocate former sex offenders who have been conditionally paroled or recently released.

Antelope Valley residents like Farrow and others who have been fighting the placement of such offenders have become activated by the potential move to relocate Christopher Hubbart, aka the “Pillowcase Rapist,” to the Juniper Hills community.

They see his placement and two others in 2021 as an escalation in the relocation of violent sexual predators into their community.

L.A. County Superior Court Judge Robert Harrison is deliberating whether to approve the move, having received 600 letters and petitions Tuesday in opposition from area residents. Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. George Gascón, Supervisor Kathryn Barger and other officials have spoken out as well.

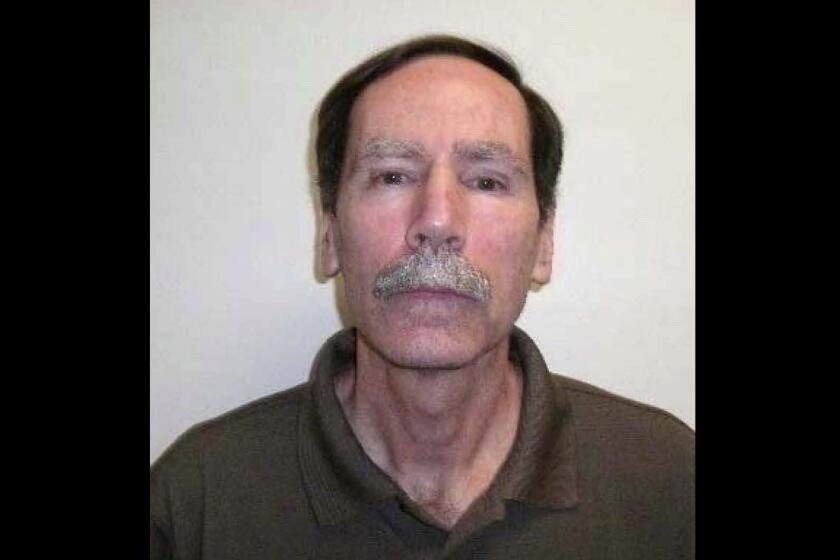

Farrow, who lives directly across the street from a previously relocated violent sexual predator, Calvin Lynn Grassmier, attended that court hearing in Hollywood along with friends Mary Jeters, Linda Adams and Diane Swick.

“We’re writing petitions, we’re attending court cases, we’re doing everything we can to stop his move here,” Farrow said. “Enough is enough. We need to be respected.”

The placement of sex offenders within the Antelope Valley, an area comprising around 545,000 residents with two sizable cities of Palmdale and Lancaster, has been source of protests for years.

There have been no recent data analysis on the exact percentage of sex offenders paroled to the region or whether the Antelope Valley is getting an outsize share of them.

But in 2014, the Antelope Valley Times labeled the region a “dumping ground for sex offenders” when it documented 876 registered sex offenders within the area, noting that the Megan’s Law database showed 673 — which still accounted for about 6% of the registered sex-offender population of Los Angeles County of 11,520 at the time, it said.

California state Sen. Scott Wilk (R-Antelope Valley) tried to address the issue in 2018 by authoring legislation that requires a paroled inmate or released registered sex offender to be returned “through all efforts reasonably possible” to the city of last legal residence or a close geographic location where the person has family, social or economic ties.

“This change in the law is great news for people living in rural and affordable areas of California, like the Victor and Antelope valleys,” Wilk said in August 2018. “Up until now families living in these areas were bearing the brunt of rehousing and rehabilitating the state’s sex offenders. That’s all about to change.”

The release of a sexual offender triggers a variety of stipulations.

The 2004 Megan’s Law created a publicly accessible database to show where sex offenders were registering to live. Jessica’s Law, passed in 2006, requires the banning of an offender parolee from living within 2,000 feet of a school or park where children congregate.

Several recent high-profile cases has sparked alarm in the Antelope Valley.

A proposal to house a violent sexual predator known as the “Pillowcase Rapist” in the Antelope Valley has officials urging residents to voice their concerns.

“What you end up getting is a case like Christopher Hubbart, a violent man who the courts say needs to be released,” said Jeters, who opposes the local placement of sexually violent predators and who runs the Facebook Group No SVP’s in the Antelope Valley. “Too many people think there’s nothing here, that we’re depopulated, so they try to place him here.”

In 2021, an L.A. County Superior Court judge released convicted sex offender Calvin Lynn Grassmier into the town of Littlerock, despite the opposition of thousands of residents. That same year, Lawtis Donald Rhoden, who sexually assaulted multiple underage girls, was also placed in unincorporated county territory near Lancaster.

Los Angeles County Supervisor Kathryn Barger this week said Hubbart’s release to Juniper Hills made no sense for a variety of reasons, including its remote location as well as weak cellphone and internet services.

“Should an emergency occur, law enforcement emergency response times are long,” she wrote in a letter. “Only two Sheriff’s deputies are assigned to the region where the proposed placement site is located. ... They alone are responsible for patrolling the southeast portion of the Antelope Valley, which spans hundreds of square miles.”

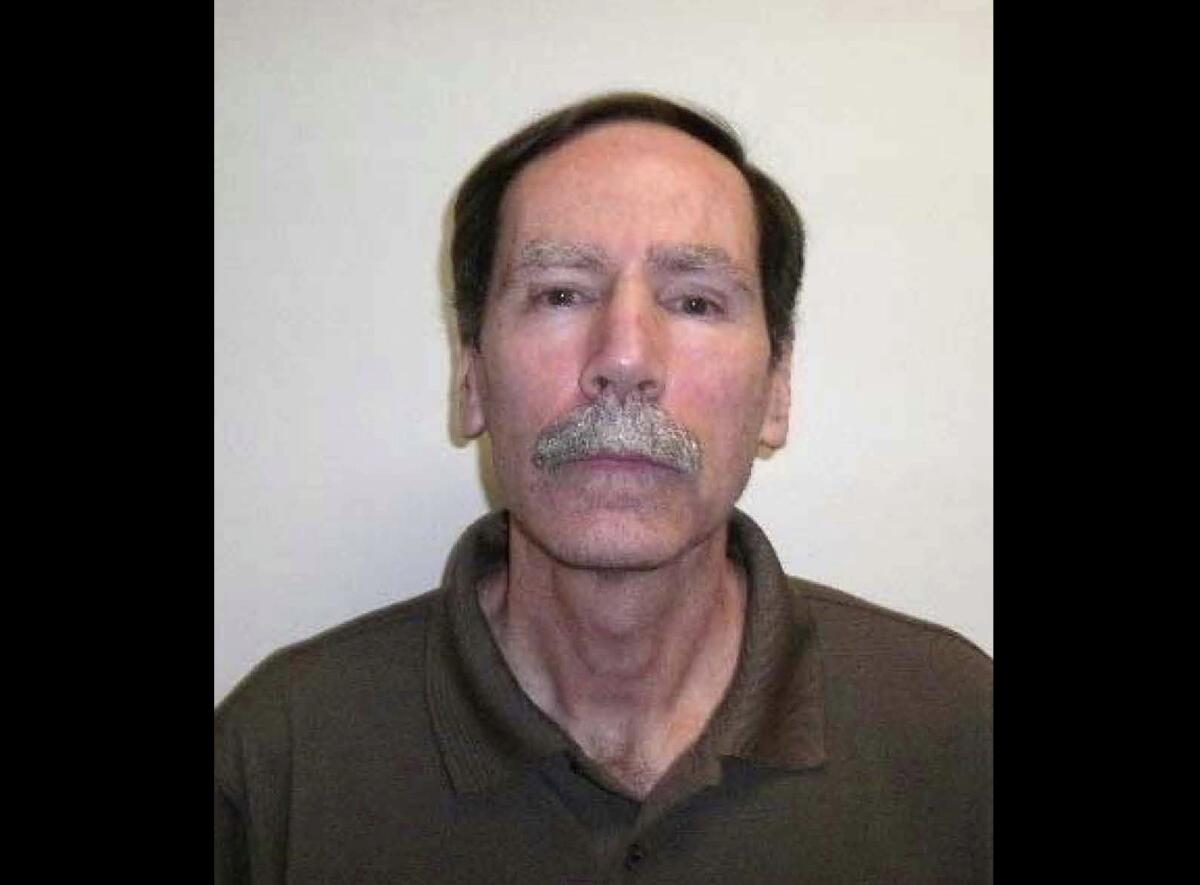

Hubbart earned the moniker the “Pillowcase Rapist” because he covered his victims’ heads with pillowcases while raping and assaulting them.

He attacked and raped women in Glendora, Hacienda Heights, Rowland Heights and Pomona, making headlines throughout 1972.

The then-21-year-old Claremont furniture worker was eventually arrested thanks to a tip of a suspicious man lurking near Brea. He was indicted on charges of rape, sodomy and attempted rape, eventually pleading guilty to some charges before being sent to a state hospital. He was released in 1979, moved to the Bay Area and was again arrested two years later and convicted of rape, burglary and other crimes.

Hubbart eventually admitted to 44 sexual assaults over 18 years.

He was committed to the Department of State Hospitals in 2000 for mental health evaluations and treatment, as is required for sexually violent offenders who are within six months of being paroled. DSH provided years of sex offender treatment to Hubbart.

It’s kind of a funny thing to folks out here in Littlerock that their recent claim to fame consists of a high school boy accused of poisoning his teacher by lacing her Diet Pepsi with cleaning fluid.

Hubbart was initially released in 2014 into the Lake Los Angeles area near Palmdale under a conditional release program, despite the opposition of Former L.A. County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey. He lived there for two years before breaking terms of his release and was remanded back to DSH’s Coalinga State Hospital.

DSH declined to disclose the nature of the violation due to patient privacy laws.

Five years later, a court recommended that Hubbart be given another chance for a conditional release.

In 2022, a Santa Clara County Superior Court determined Hubbart should be housed in Los Angeles County. In March 2023, that court ruled that Hubbart was indeed suitable for conditional release, and a search process for his home was commenced by DSH’s housing contractor Liberty Healthcare.

A DSH representative reiterated it was the courts that “decide if an individual designated as an SVP may be placed into outpatient treatment.”

Liberty found a residence in Juniper Hills, one that Judge Harrison said he would take great care in considering, as if he was living in the area.

Juniper Hills resident Diane Swick, 60, transitioned from joy to despondency quickly in early August.

The retired dental specialist received a pacemaker in July to treat heart failure that caused fatigue and difficulty breathing for months.

Leaders of Antelope Valley’s new USL League One team say they have received strong community support before even revealing the team’s name.

Two weeks into her new lease on life, Swick said she heard about Hubbart and sat at home for a week, fearful that Hubbart was potentially moving to an adjacent property 300 feet away.

“I don’t get depressed, but I couldn’t move, I was stricken with fear,” Swick said. “I didn’t want to do anything and I felt like my world, my life, was being ruled by someone else.”

Like Farrow, Swick raises horses along with a variety of animals. What she finds most endearing about her local community is its safety and security.

“I can leave my back door unlocked and not worry about someone breaking in,” she said. “I can leave my car unlocked and not worry.”

She sat in the court bewildered as to why an upscale community such as La Crescenta successfully blocked the placement of Grassmier in 2021 but “the AV is ignored.”

“Sometimes I wish the courts would see what they’re jeopardizing here, and I wish Liberty Healthcare would actually take us into consideration,” she said. “This is a community recovering from wildfires — particularly the Bobcat fire — and this is a blow.”

Swick, however, continues to fight. She and her friends submitted letters to Harrison while raising community awareness through social media and town gatherings.

“What can we do but speak up and let people know we’re here?” Swick said. “We’re not sad. We’re determined.”