Thousands are housed as L.A. County makes progress on Skid Row

Mike Juma sat at the end of the bed in his ninth-floor one-bedroom apartment in downtown Los Angeles, staring at the mountains visible from his window.

“I don’t like high-rises,” he said. “But look at that gorgeous view. That’s what they call a million-dollar view.”

A year ago, Juma, 64, was in a vastly different place in life. He was living in a tent on Skid Row, selling cigarettes to make money and sleeping with a samurai-style sword by his side for protection.

Now, he’s in a furnished apartment listening to the soft whooshing sound of the air conditioner.

Juma is among a wave of unhoused people who have moved from Skid Row into interim and permanent housing over the last year. It is all part of a $280-million county initiative to house more than 2,500 people, boosting health, drug treatment and related services in the 50-block neighborhood that has become synonymous with poverty and homelessness.

The initiative, dubbed the Skid Row Action Plan, also is an effort to counter the systemic racism that has driven people to Skid Row — where an outsize number of Black people fill sidewalks and encampments — by trying to transform the neighborhood into a thriving community.

Los Angeles County Supervisor Hilda Solis, whose district includes Skid Row, initiated the project, which launched a year ago after months of planning and organizing. So far, the county has moved nearly 1,000 homeless people into permanent housing and nearly 2,000 into interim housing such as shelters and transitional housing, according to data recently released by the county’s Housing for Health program, which is leading the project.

The data also showed that younger people between the ages of 18 and 40 were more likely to be placed in interim housing, whereas older people ages 55 and over were placed in permanent housing.

At the time of the project’s launch, 4,402 people were experiencing homelessness on Skid Row, with more than half living in a tent or makeshift shelter, many of them Black or Latino, according to the 2022 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count. Today, the population stands at 3,791, a decrease of nearly 14%. The number of people living outdoors also decreased by 22% over the last two years from 2,695 to 2,112.

“We got very focused with this,” said Elizabeth Boyce, deputy director for Housing for Health. “We stuck with the main components of solving homelessness and things we know we can deliver on.”

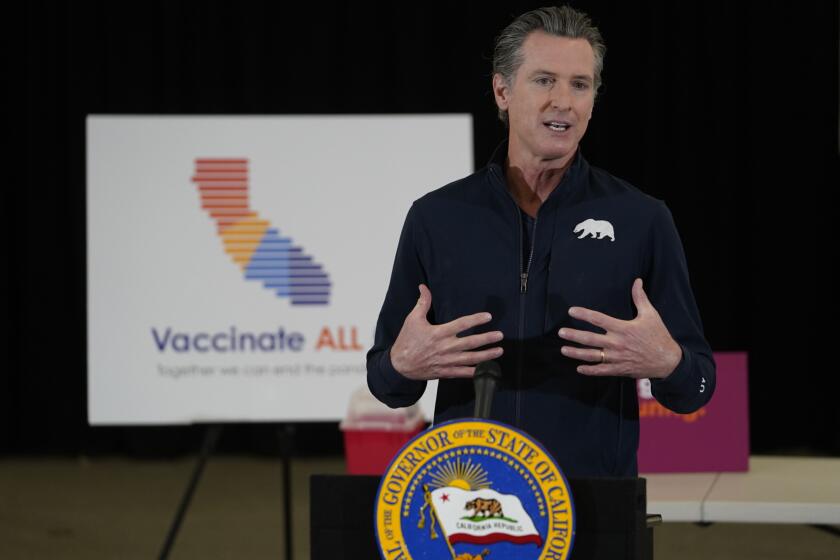

The progress comes as counties and cities are facing pressure from Gov. Gavin Newsom to clear out homeless encampments in the wake of a Supreme Court ruling that said cities may enforce laws restricting homeless encampments on sidewalks and other public property. Adding to the pressure is the upcoming 2028 Olympics.

Solis praised the agency and its partners for the quick turnaround.

“With a goal of permanently housing 2,500 people in three years, one year into the program, we are more than one-third of the way there,” Solis said in an email. “The crisis we have on Skid Row has been years in the making, and we all need to work together to address it by focusing on prevention, early intervention, and providing access to evidence-based treatment services.”

Government officials have long tried to address homelessness on Skid Row. In the early 1970s, for instance, proponents of development wanted to demolish much of the area while others advocated to preserve the neighborhood’s low-income housing and services as a way to keep people on Skid Row, which became known as the “containment plan.”

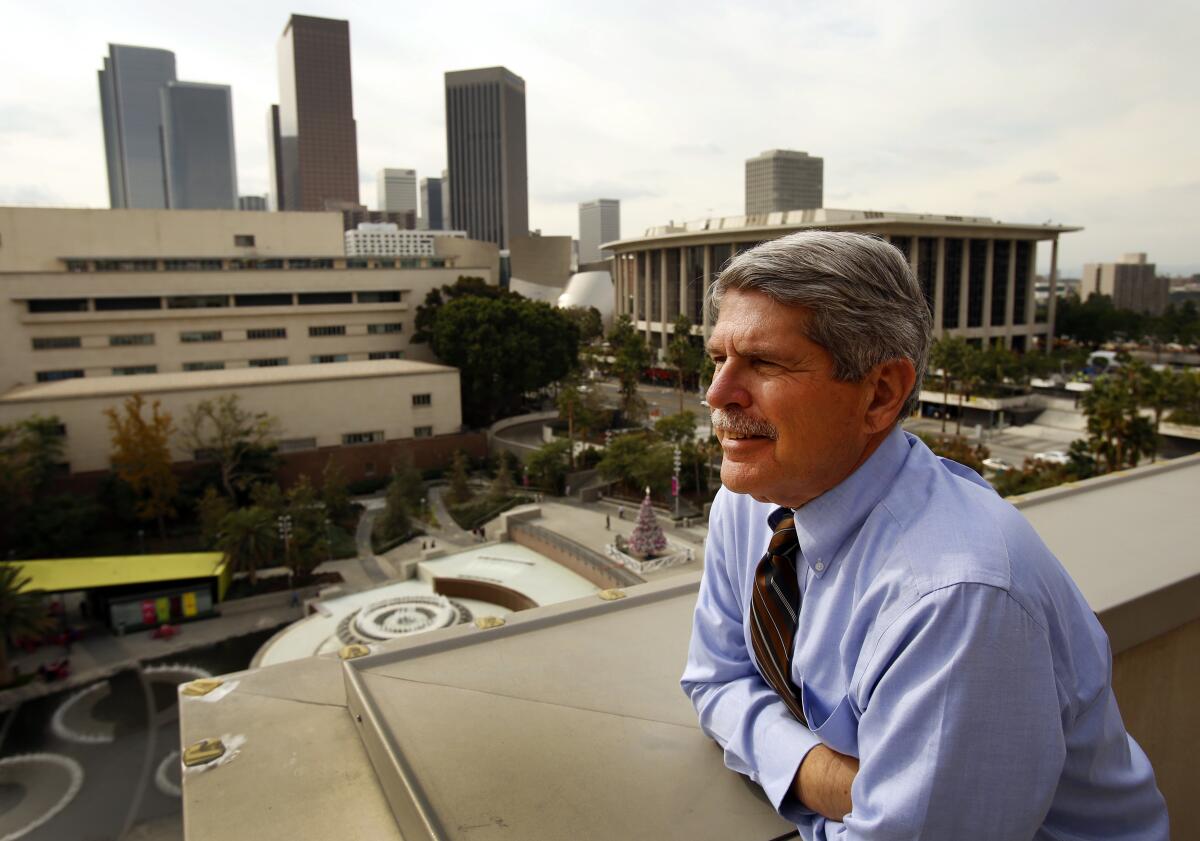

In 2007, then-Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky launched Project 50, a pilot program aimed at housing 50 of the most chronically homeless people on Skid Row through a housing-first approach. He sought to expand it but was unsuccessful.

Boyce said what makes the Skid Row Action Plan unique is that it was designed to address the complex needs of the neighborhood with help from Skid Row residents, service providers and other stakeholders. It also leverages resources the county is already using to address the homelessness crisis in the region.

“We were really thinking from the beginning,” she said, “how do we create thoughtful, compelling change ... not changing the people that live there but changing the support that people receive.”

“You have to have some early wins and show you’re talking business.”

In June 2023, the project got a significant funding boost when Housing for Health and its partners, the city of Los Angeles and the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, received a $60-million state grant to fund the project through 2026.

Boyce said the funds were crucial in the project’s early success. They helped create 350 new interim housing units and 750 new permanent units, and increased and improved outreach services.

The funds have also helped establish a “safe landing” in the lobby of the Cecil Hotel; people can walk in at any time of the day or night to receive medical care and housing services. The money also created a navigational center in Skid Row to help providers access interim housing for clients as fast as possible.

A part of the state grant also went to support a program run by the Downtown Women’s Center that aims to end homelessness for women and families in Skid Row. The funding allowed 453 women to be placed in permanent housing and 737 into interim housing, which contributed to a 42% drop in unsheltered women from 2022 to 2024, according to the homeless count data.

County officials say their work is far from over. They plan to create residency advisory councils that will oversee key areas of the Skid Row Action Plan. Additionally, they expect to build a Harm Reduction Health Hub to provide drug testing and detox beds and to provide referrals to rehab centers, among other services. There also are plans to establish a safe site zone — a large outdoor park on Skid Row where people can visit and engage with various agencies to access government benefits and programs.

Last week, on the ninth floor of Weingart Tower, Juma lighted a cigarette.

“It’s like adjusting to a new car smell,” he said of his new digs, his voice raspy. It’s “different.”

Juma’s tower sits on Skid Row and includes 228 studios and 47 one-bedroom apartments. At least 40 units are reserved for veterans. Juma served in the Marines.

How Juma ended up on the street is not clear. He said he once had a cross-country trucking business, delivering fish. There were money and tax issues, and eventually he lost the business and everything that came with having a stable job.

A fondness for drinking was part of the story, although he says that wasn’t a factor.

When he became homeless, he said he returned to an area he was familiar with. He set up a tent near 6th Street and Towne Avenue, not far from seafood businesses.

He said he got used to living outdoors, even if it was tough at times. At night, he rarely slept amid people screaming, loud music and fighting. Then there was the early traffic of commercial trucks.

“You hear everything,” he said. “You’re like a blind man, you hear footsteps, you can’t sleep.”

Last year, he said he was ready to get off the streets after he injured a man during a fight. Standing over the bleeding man, he said, he knew he’d had it.

“I almost killed him,” he said. “I’ve had a lot of fights; you sometimes come out a winner, but you never really win.”

So he approached outreach workers with Housing for Health. They quickly found him a temporary place to stay. He then applied for supportive housing and waited several months. A week ago, he was told an apartment was available for him.

He said he had spent the three days since he moved into his new apartment sleeping. Behind him on the bed was a brown pillow with the words: “God has not forgotten me.”

Juma said the apartment came with a new fridge, stove, television and, happily, a bathroom. He said the kitchen cabinets were filled with plates, pots and cooking utensils.

But the window is the most symbolic feature of his new home. As he considers the possibilities that lie ahead, he can glimpse his past life. High up in his room, he said, he can make out the street where he lived in a tent.

Sometimes, he said, he looks down and thinks: “Things did turn out all right in the end.”