- Share via

In Little Tokyo, the past and the future have long been at odds.

Less than a month after the iconic Suehiro Café closed its 1st Street location — evicted after nearly 40 years — community leaders gathered, shovels in hand, to mark the start of construction of an ambitious housing complex a block away.

Little can offset the departure of Suehiro from the historic storefronts on this historic block. But the groundbreaking in February of the First Street North complex is considered a victory by those who argue that Little Tokyo has for too long been a target for opportunistic development by city planners, overseas corporations and absentee landlords.

“We need to define our future,” said Erich Nakano, executive director of the Little Tokyo Service Center, which played a major role in getting First Street North green-lighted.

Outsiders, Nakano explained, have played an outsized role determining the direction of the neighborhood, a center of Japanese American life in Los Angeles celebrating its 140th anniversary in August.

Being built on nearly two and a half acres that were once a part of Little Tokyo’s post-war streetscape, leveled in the 1960s and left to languish as a city-owned parking lot, First Street North is a $168-million mix of affordable and supportive housing, a park and commercial space.

The site will include a memorial honoring Japanese American veterans of World War II built by the Go for Broke National Education Center, which helped develop the First Street North project with the Little Tokyo Service Center.

Their efforts, including more than 10 years of negotiations, culminated in 2018 in a series of collective actions — street protests, a petition, art exhibits — that wrestled final approval from city officials.

First Street North is the latest example of Little Tokyo leaders leasing property from the city and developing projects that they hope will benefit the community.

Their work is taking place as broader changes sweep through Little Tokyo. Once an immigrant hub, this vibrant downtown district is a tourist destination where a 121-year-old mochi shop co-exists with sneaker shops and where weekend crowds search for ramen and the perfect Instagrammable moment.

This vitality, however, is challenging what Little Tokyo has traditionally stood for as an ethnic community defined by its history.

“This neighborhood is not just for Japanese Americans but for Asian Americans and for Los Angeles,” said Kristin Fukushima, managing director of the Little Tokyo Community Council, one of the organizations backing the First Street North project. “We could just give up and let the forces of free market and capitalism wreak destruction on this community, but we still have stuff that we can fight for.”

Preservation has never been a strong suit for Los Angeles, where landmarks and neighborhoods have been torn down or repurposed with fleeting regard. Economic exigencies are often more urgent than a deference to the past, but Little Tokyo is trying to have it both ways.

For the record:

5:44 p.m. Aug. 5, 2024A previous version of this article referred to retailer Mokuyobi as Molu Yobi.

At retailers like Mokuyobi, Monkey Pants and Sanrio, business is brisk for the latest multi-colored backpacks, plushies and Hello Kitty merchandise, while the gift shop Rafu Bussan still finds customers for imports like sake glassware, Hasami porcelain and Kaga dolls.

Here, as elsewhere, internet commerce is forcing turnover. Little Tokyo Arts and Gifts and Mikiseki, a watch and jewelry repair shop, have closed, and Little Tokyo Cosmetics is now a boba joint.

Underlying the turnover is a wider demographic shift. Over the decades, immigration from Japan has slowed, while families have put down roots over four or five generations. For many locals, the South Bay, with its profusion of Japanese supermarkets and restaurants, has eclipsed Little Tokyo for everyday shopping and eating.

Some Little Tokyo businesses that served Issei and Nisei — Japanese immigrants and their American-born children — have closed or are struggling, while others have found a way to evolve and thrive.

Mikawaya, where community icon Francis Hashimoto invented mochi ice cream, closed two years ago after more than a century. A block away at Brian Kito’s Fugetsu-Do sweet shop, established by his grandfather in 1903, lines form to the sidewalk for the mochi and manju.

Landlords are trying to adapt. Tony Sperl, owner of the building where Suehiro Café was, leases adjacent space to a vintage clothing shop and tattoo parlor.

Sperl initiated the eviction more than a year ago, claiming nonpayment of rent. Suehiro’s owner, Kenji Suzuki, denies the accusation, saying the checks were mailed but never cashed.

For a time, there were rumors that Suehiro was to become a marijuana dispensary. Sperl denies that and says the new tenant is a restaurant featuring Asian cuisine.

“What is the future of Little Tokyo?” he asked. “You might as well ask me what is the future of L.A. I don’t know. The city is changing so much.”

Suzuki, who has since relocated his restaurant a half mile away, also wonders what lies ahead for the community he grew up in. “It may be Little Tokyo in name only and not have anything to do with the Little Tokyo that we know,” he said.

As the third generation of his family to own the mochi shop, Kito is taking the long view. “There has always been gentrification, and if the community is strong enough and works together, it will manage it,” he said.

When the National Trust for Historic Preservation named Little Tokyo as one of America’s 11 most endangered historic places in May, it hoped to bring attention to the fragility of the community.

Activists have been arguing this for years and would like to tap the brakes on a future they feel is misaligned with the past. Particularly alarming to them are plans for a nearby rail line, an expansion of the Civic Center and a mega-development at 4th Street and Central Avenue, considered by some too disruptive, intrusive and too big.

Mark Masaoka, 70, a member of Nikkei Progressives, is concerned that the community is at risk of “hollowing out,” of becoming a shell less connected to Japanese and Japanese American culture.

“A community is more than a collection of businesses,” he said. “It is a social and neighborhood fabric comprised of interrelationships of people who own and work at these businesses.”

For some, losses like Suehiro trigger memories of a much larger trauma. In 1942, Little Tokyo residents left their homes and businesses behind as the U.S. government forced them and 125,000 others of Japanese ancestry into remote incarceration camps.

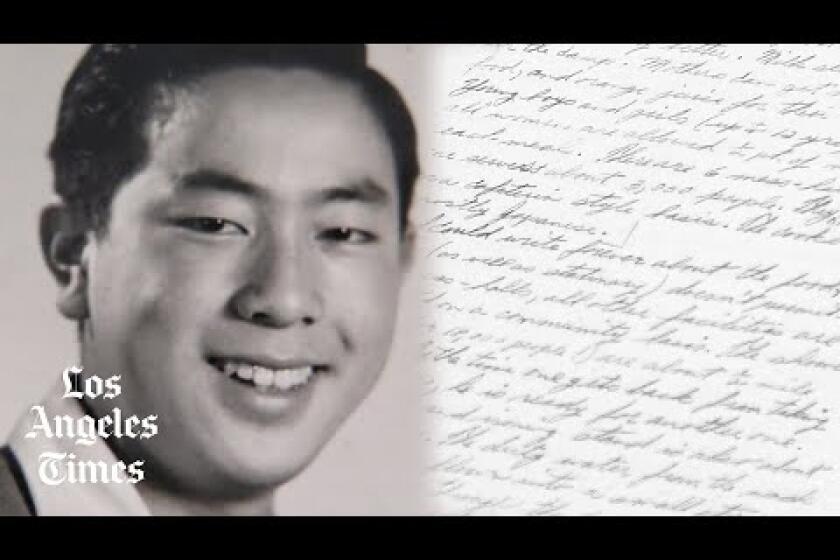

Japanese Americans were held at the race track before being shipped to incarceration camps. My uncle’s letters reveal the indignities of living there.

“This sense of displacement — and not having control — is a driving force for why people are fighting to preserve Little Tokyo and want to have an active say over its future,” said Nakano of the Little Tokyo Service Center.

After the war, many Japanese Americans settled in other parts of the L.A. area yet still returned on weekends to the community they once called home.

At the time, politicians were dreaming big at the expense of poor, non-white neighborhoods. Freeways were cut through East Los Angeles. Dodger Stadium was built in Chavez Ravine, and planners eyed Little Tokyo for the expansion of the Civic Center.

One of the first blocks to go was across the street from First Street North, where in 1949, according to The Times, there were “968 persons now occupying 716 rental units.”

The LAPD’s Parker Center headquarters went up on the site, then it was torn down in 2019. As the city continued to push into Little Tokyo, it soon claimed the First Street North site, which became a parking lot for police vehicles.

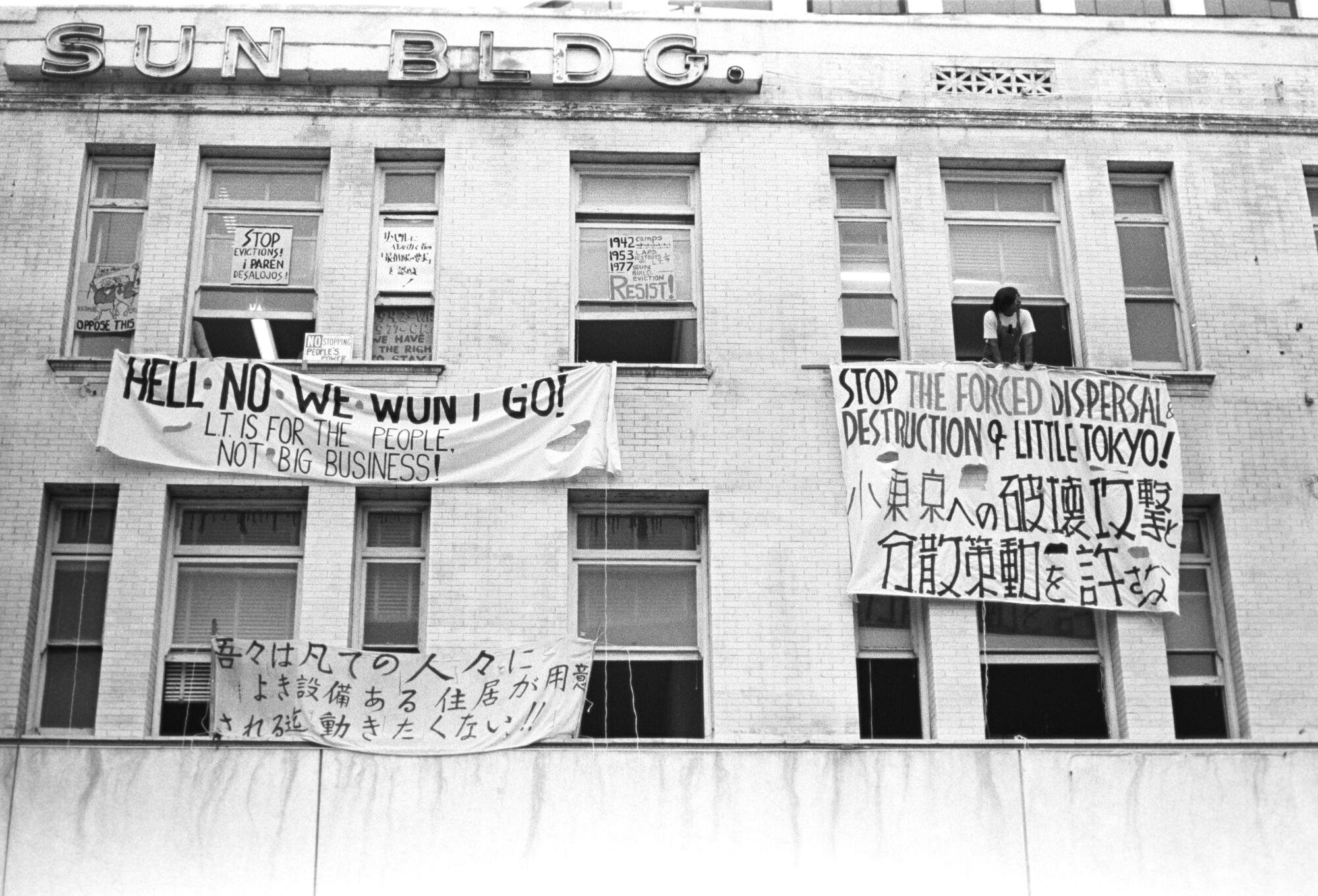

In the 1970s, activists could not stop the city redevelopment agency’s plans to raze the Sun Hotel and Sun Building. Japanese corporations financed the construction of Weller Court and the New Otani Hotel on the site.

Leaders of the Little Tokyo Service Center, established in 1980, realized they had limited power to prevent private property owners from raising rents or evicting tenants. With the help of community redevelopment funds, their strategies changed.

“We focused on publicly owned land,” said Nakano. “We learned early on that this was the most efficient way to control our destiny.”

The Service Center leaders successfully marshaled community forces against the city’s plan to demolish an aging apartment building, then convinced the city to let them purchase and convert the old Union Church next door into an arts complex, which opened in 1998.

Then in 2011, state legislators abolished community redevelopment agencies, a significant source of funding. Two years later, a coalition of community groups created an initiative, known as Sustainable Little Tokyo, to guide future development around the goal of “a healthy, equitable and culturally rich Little Tokyo.”

Two of the Service Center’s recent projects are a community gymnasium called the Terasaki Budokan, which was completed in 2021 after 30 years of planning, and First Street North, scheduled to open in 2026.

Both projects were funded through state and federal grants, low-income housing tax credits, developer fees, conventional loans and private donations.

Looking ahead, the Service Center is hoping to develop one of the last open parcels in Little Tokyo, a city-owned parking lot across the street from the Japanese American National Museum.

At a time when many are mourning the relocation of Suehiro, First Street North has become a lesson for other communities seeking to take control of their destinies.

Not only does the development hit the marks for affordable housing — apartments for low-income families, unhoused veterans, people with AIDS — but it hopes to attract legacy businesses with discounted rents. Suehiro’s owner has expressed interest.

From his office in the Little Tokyo Service Center, Nakano acknowledges continuing challenges, including “commercial property turnover and homelessness.” But he knows what can be accomplished when community members advocate for themselves, citing the reparations won in 1988 for those incarcerated during World War II.

Similarly, the Little Tokyo Community Impact Fund, started in 2019 to purchase properties that could be leased below market rates, is proof of a willingness to dream big, he argues.

In the aftermath of the pandemic, the fund has raised about $800,000, which, according to fund president Bill Watanabe, is a strong start but still short of its $2-million goal.

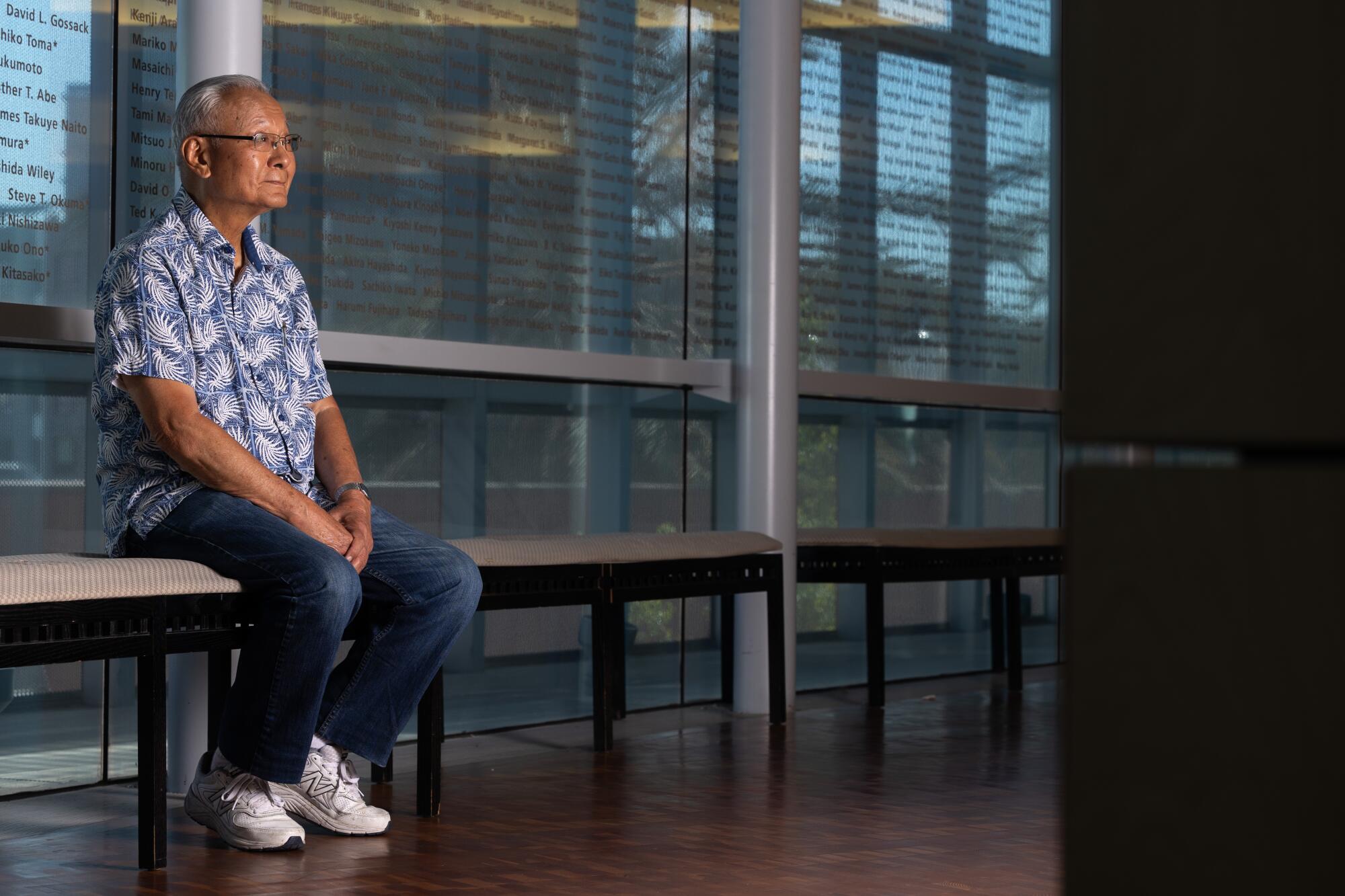

Watanabe, 80, who was born in the Manzanar incarceration camp and was the founding executive director of the Little Tokyo Service Center, remains committed.

“Little Tokyo will never be what it once was. We can never go backwards,” he said. “But it does represent a long-term piece of Los Angeles’ history, and we don’t want people to forget that we are here.”