Column: Reparations for Chavez Ravine families? Not so fast, say some descendants

Larry Herrera-Cabrera’s email to me in May was as polite as it was challenging.

He reached out shortly after The Times editorial board wrote about proposed state legislation that would attempt to right the wrong of Chavez Ravine.

Sponsored by Assemblymember Wendy Carrillo, the bill would require the city of Los Angeles to erect a monument to the families, most of them Latino, who were pushed out in the 1950s to make way for Dodger Stadium. The city would also have to create a task force to study reparations for the “large, long-lasting disparities” faced by those families and their descendants.

Bemoaning what happened in Chavez Ravine is part of the modern L.A. gospel. I’ve read essays by former residents decrying what happened, read books and seen plays and documentaries that captured their plight and enjoyed Ry Cooder’s 2005 concept album, “Chávez Ravine,” which gathered Chicano music legends — Little Willie G, Lalo Guerrero, Ersi Arviz and Don Totsi, among others — to sing about the sordid saga from beginning to end.

That’s why I found Herrera-Cabrera’s email so fascinating.

“My wife and I are both descendants of three families that lived in Chavez Ravine up to 1950,” he began. “Despite the legislative findings in [Carrillo’s bill], and fables on the Internet and elsewhere, our families were neither left destitute, nor were they bitter about moving.”

A community was uprooted for the land that became home to Dodger Stadium. The city of Los Angeles should make amends to the displaced families of Chavez Ravine.

He went on to offer an alternative narrative I had never considered — one where Chavez Ravine families took the money the city gave them, bought homes elsewhere and went on with their lives. Where descendants feel insulted at the insinuation in Carrillo’s bill that they need help. Herrera-Cabrera’s note added nuance to a tale long considered an open-and-shut, black-and-white case of municipal racism.

Priscilla Leiva, professor of Chicana/o and Latina/o studies at Loyola Marymount University, has spoken with Herrera-Cabrera as part of “Chavez Ravine: An Unfinished Story,” a multidisciplinary project she’s leading with former resident Carol Jacques that includes hundreds of photos and dozens of oral histories. She wasn’t surprised that I was, well, surprised.

“Latino narratives are always flattened, but especially with [the Chavez Ravine] population, because the displacement was so egregious,” Leiva said.

The public long ago stopped paying attention to “what happened before and what happened after,” she noted, which means “a lot of people don’t want to recognize or acknowledge any nuance.”

I visited Herrera-Cabrera and his wife, Katherine, at their spacious San Juan Capistrano home earlier this month. It’s nestled on a hill resembling the neighborhoods where their parents grew up, except this is upper-middle-class suburbia instead of the “poor man’s Shangri-La,” as a photographer famously described Chavez Ravine and as Cooder titled a song.

In Herrera-Cabrera’s study, a Biden-Harris sticker was wedged above a photo of his late mother Sally, alongside photos of his biological father and maternal uncles in their World War II uniforms. He described his decades in city and county government as a “progressive bureaucrat,” proudly remembering how he stood up to racist politicos in Santa Barbara County in the 1980s and officiated same-sex marriages as Long Beach city clerk after the Supreme Court legalized them in 2013, two years before he retired.

“Having that connection to [helping] the community was really important to me,” he said as we stood over a kitchen table to look at family photos shot around Chavez Ravine in the 1940s. Three of his maternal uncles in Army uniforms around their mother at a park. His mother and her sisters, wearing sunglasses and bobby soxer skirts and sweaters. A group of unidentified young pachucos.

“Our family’s history gave us strength,” the 71-year-old continued. He’s tall, with bright eyes that make his glasses shine even more. “I know they suffered hardship. Things don’t always work out, but you gotta keep pushing.”

His grandparents used the money from the city of L.A. to buy a home in nearby Lincoln Heights, where Herrera-Cabrera was born in 1952. Nine years later, his mother and stepfather moved to Rosemead but frequently visited his Uncle Joe in Solano Canyon at the base of Dodger Stadium, where some Chavez Ravine families had relocated. City officials had promised them a spot in a public housing project to be built over their bulldozed homes. The stadium went up instead.

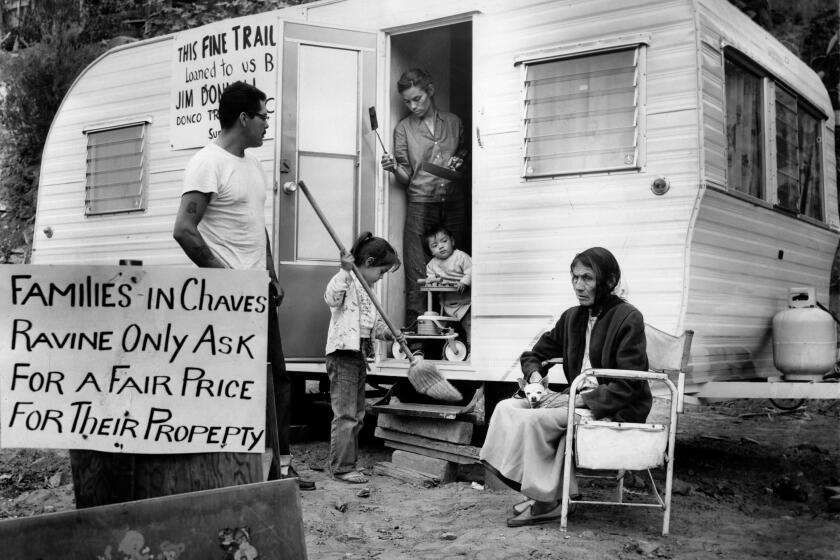

Most residents of Chavez Ravine had been relocated in the early 1950s, but a proposed public housing project was scrapped.

“In the early days, you could sit on a hill and watch the games for free,” Herrera-Cabrera said. He and his family sometimes went to games, but he preferred playing with cousins outside the house of a family friend while their elders listened to the game on the radio and reminisced about Chavez Ravine. “They spoke fondly of those days. No one complained about having to move.”

He can’t remember when he learned of the prevailing narrative casting the Chavez Ravine families as pitiable, but he “didn’t care for it.” Nor did Katherine, who eventually joined us in the kitchen.

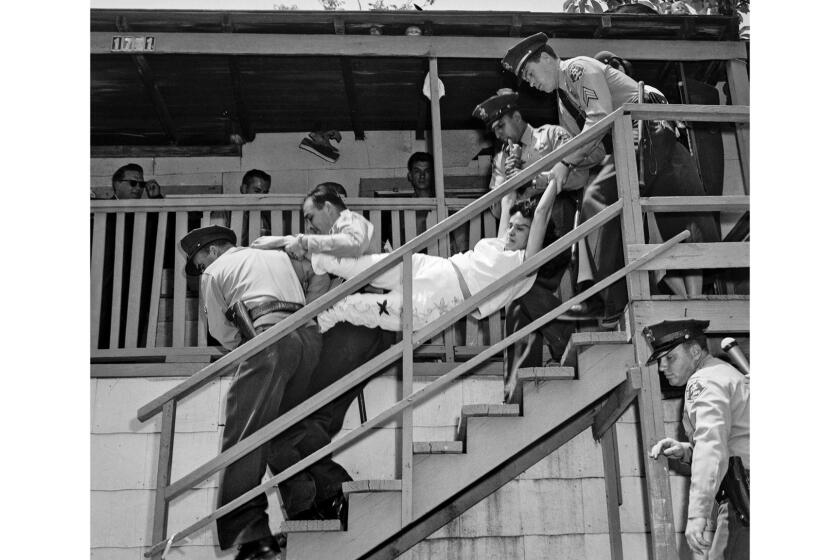

“Who wants to admit that they’re downtrodden?” she said before referencing the Arechiga family, one of the last holdouts in Chavez Ravine before L.A. County sheriff’s deputies forcibly evicted them. They had lived at their condemned home without paying property taxes for years, according to newspaper accounts at the time.

“Now they come back saying they want reparations?” she said.

“[Chavez Ravine] is more than just the photos of people being dragged out,” Larry Herrera-Cabrera added, referring to the infamous 1959 photo of four L.A. County sheriff’s deputies dragging a member of the Arechiga clan from her home. “It’s their accomplishments.”

His perspective about what Chavez Ravine should mean changed in 2019, after a trip to the Ardennes American Cemetery in Belgium to fulfill a promise to his mother. There lies the grave of his maternal uncle, Henry Rivas, an Army private who died in the Battle of Hürtgen Forest at 19. Between them, Larry and Katherine have at least a dozen relatives who served in World War II.

“To think they thought that fascism was worse than what they faced at home was telling,” she said.

“And then they returned and became successful,” Larry added. “I had one uncle who worked in aerospace, and my Uncle Joe worked in the post office. Another uncle opened a restaurant. My dad Domingo did construction. My Uncle Ted — Teodoro — he started a men’s fashion line.”

Last year for the first time, the couple attended an annual reunion of Chavez Ravine families who call themselves Los Desterrados (The Uprooted). There, Larry displayed poster boards of his uncles’ World War II service.

“If I could talk to Wendy [Carrillo], I’d tell her those stories,” he proclaimed. “To me, they were successes. That’s part of the story. As difficult as it was, they still prospered.”

He sent a letter to the state Senate opposing Carrillo’s bill, which is being considered by a Senate appropriations committee, describing it as “hypothetical” and bad policy.

“If people were truly ripped off, that’s one thing. But why would I, as a descendant, be entitled to anything?” he said.

“The bill says people were left destitute,” Katherine said. “Who?”

Three protesters wanted to remind L.A. about the Latino families uprooted to build Dodger Stadium. But even many Latino fans just aren’t interested.

Vincent Montalvo is a co-founder of Buried Under the Blue, a nonprofit that has long pushed for an apology from the Dodgers and reparations from L.A. County and city while urging people not to use the term “Chavez Ravine” for the neighborhoods of Bishop, La Loma and Palo Verde that were bulldozed to make way for Dodger Stadium.

But they had nothing to do with Carrillo’s bill, which he said he “85% agrees with.” His group also wants three community centers to be built and named after Bishop, La Loma and Palo Verde. The land should be given back to the Gabrieleño Band of Mission Indians, Kizh Nation, and all the parties involved in the displacement should issue a public apology, according to Buried Under the Blue.

Montalvo, who grew up in Echo Park and whose grandparents owned a home in Palo Verde, said former residents have accused him “of wanting a handout.”

“These things hurt,” he said. “But the older generation couldn’t even talk about what happened for forever. But I’ve told them, ‘With respect, you guys do what you’re going to do, and we’re going to do what we’re going to do. And some of you are going to jump back on the wagon, and that’s OK.’ ”

Carrillo, whose district includes Dodger Stadium, told me, “I’ve learned that when advancing policy ideas, some will say it goes too far, while others may say it doesn’t go far enough. But ultimately, we move the needle toward justice, and we try to do as much good for as many people as possible.”

On the criticism that her bill casts Chavez Ravine families as perpetual victims, the Assembly member was more straightforward: “There are no victims, but there are survivors.”

Larry agrees with her and Montalvo on one thing: a monument. But he wants it to focus on the good of his elders, as much as the bad that happened to them.

“My family wasn’t dragged out of Chavez Ravine. Most families weren’t. Like my Uncle Joe would say, let it go like water off a duck’s back.”

He teared up.

“If there were reparations, well, bring them back,” he said, referring to his uncles. “Bring back their stories. I didn’t suffer. It should be about what they did. That is Chavez Ravine’s legacy.”