- Share via

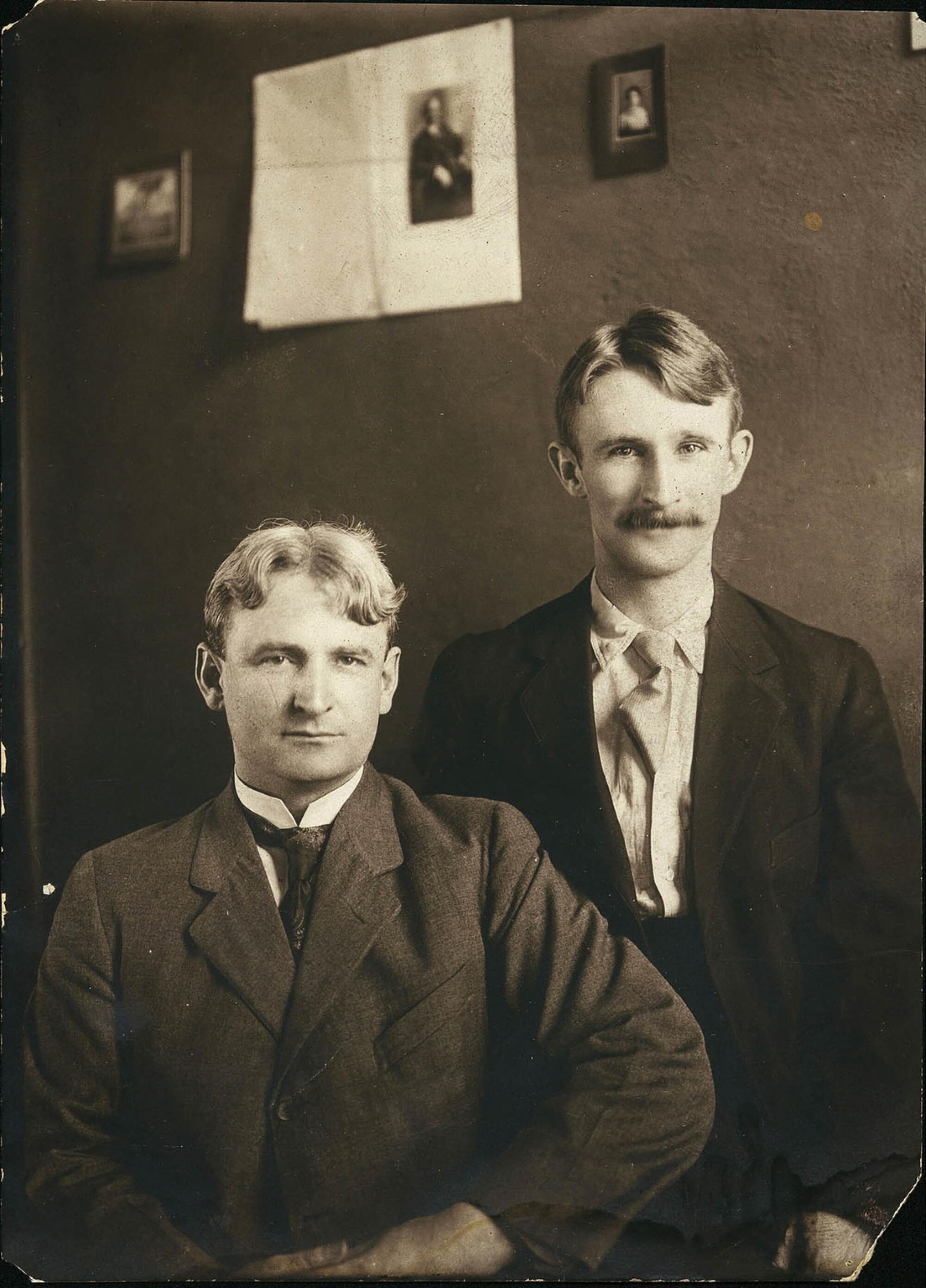

The man who would blow up the Los Angeles Times sat in a hotel room, preparing the dynamite. He was gaunt and tubercular, in his late 20s, with a feral air and a walrus mustache. He had a reputation for hard living: cigarettes, whiskey, brothels. A union man through and through, James B. McNamara had come to the West Coast to send a message to the enemies of organized labor.

In this series, Christopher Goffard revisits old crimes in Los Angeles and beyond, from the famous to the forgotten, the consequential to the obscure, diving into archives and the memories of those who were there.

For years, he had participated in a nationwide spree of industrial bombings, directed by his dapper and well-spoken older brother, John J. McNamara, an official with the Bridge and Structural Iron Workers Union in Indianapolis. The younger McNamara made $200 per mission. He spoke of himself as a foot soldier in a holy war.

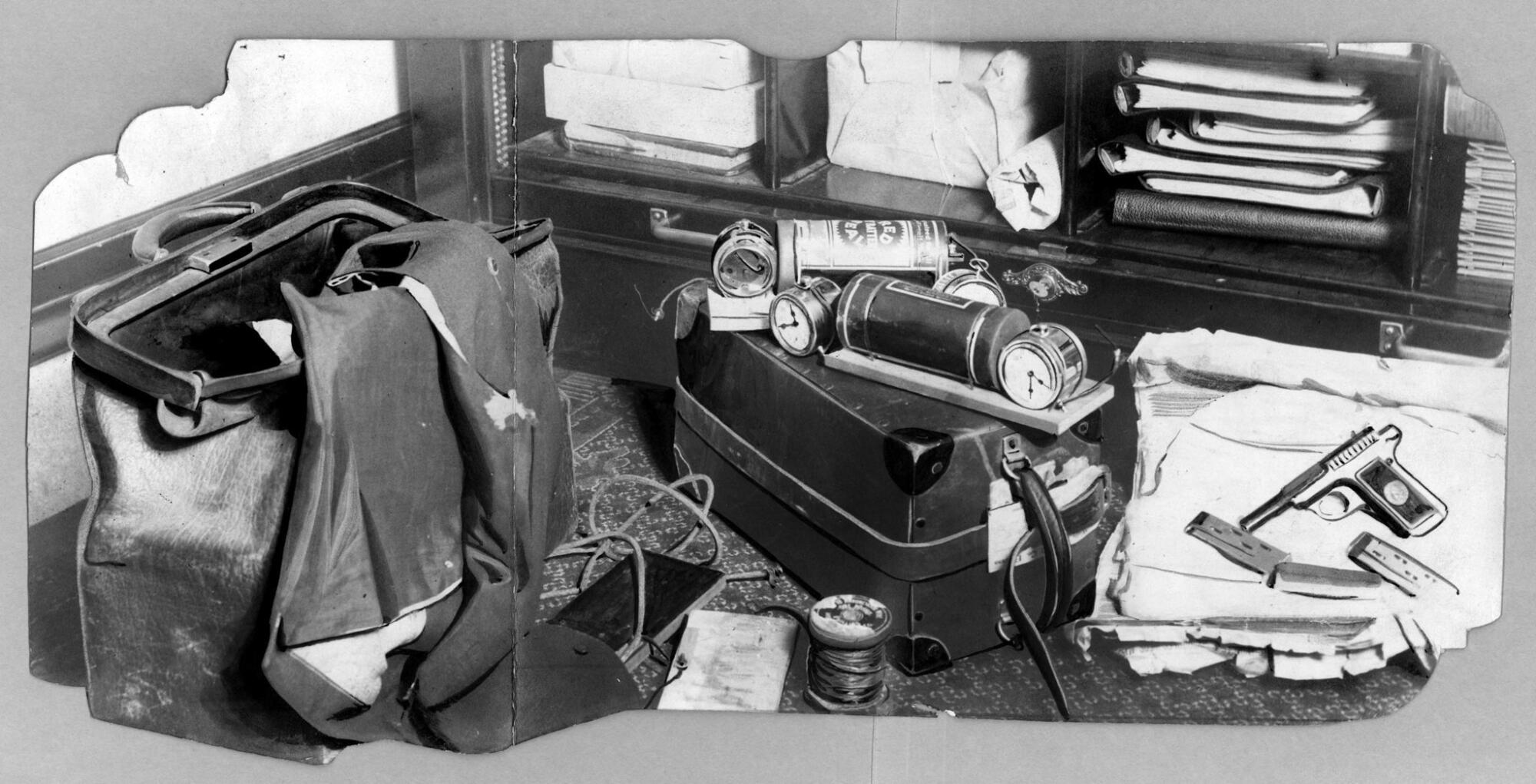

In his third-floor room at the Baltimore Hotel in downtown Los Angeles, McNamara hunkered over three simple time bombs. They were a relatively new innovation; authorities called them “infernal machines.” Until recently, bombers had to light a fuse and run; now they could wind up a tiny alarm clock and walk away.

It was Sept. 30, 1910. McNamara would plant three bombs that day. One he hid against the side of a house on Garland Avenue, where the president of the anti-union Merchants and Manufacturers Assn. lived with his family. Another bomb he planted at the Wilshire Boulevard home of Los Angeles Times Publisher Harrison Gray Otis, whose battle against organized labor had made him widely hated among the movement.

The third bomb J.B. McNamara carried toward the stronghold of Otis’ empire, the brick-and-granite Times building at Broadway and First, which the 73-year-old publisher called “The Fortress.” McNamara slipped into Ink Alley, a publicly accessible passageway at street level where the newspaper stored barrels of petroleum-based printers ink. He left the suitcase holding the bomb and jumped on an overnight train out of town.

It was a cruel era in the battle between labor and capital, marked by a ruthlessness that is hard to imagine today. Across the country, companies enlisted cops, militias and private guards as strikebreakers, with bloody results. On the other side were men like the McNamaras.

In the 1910s, bombs detonated with regularity at nonunion construction sites — bridges, viaducts, rail yards, foundries, derricks — and proved an effective tactic in winning union contracts. In state after state, businesses weighed the costs of further wreckage and capitulated.

“Probably 90 bombings had gone uninvestigated because the local police had no interest,” says Michael Digby, a bomb expert who worked at the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department and now teaches about the case.

That industrial sabotage had done damage mostly to property, not people. Scattered police departments, if they investigated at all, did not share information with one another. The bombers boarded trains to new cities, new targets.

The bombers “got seduced by success,” says Paul Greenstein, a researcher who co-wrote the book “Bread & Hyacinths: The Rise and Fall of Utopian Los Angeles,” about the period. “They bombed a lot of places, and they never got caught and managed to squeeze people into signing their contracts for union labor. They didn’t stop until they failed and murdered people.”

In 1910, Los Angeles seethed with labor trouble. With Otis’ support, the City Council had passed an anti-picketing law that led to mass arrests. To the unions, it was “the scabbiest town in the United States.”

At 1:07 a.m. on Oct. 1, 1910, an alarm clock went off in Ink Alley, 16 sticks of dynamite ignited, and people began dying. There were about 100 workers in the Times building — Linotype operators, stenographers, printers, machinists, compositors.

The initial explosion tore a hole from the basement to the roof and generated fireballs that raced through the corridors, feeding on wooden furniture, rolls of paper and ink. Survivors would remember multiple explosions as gas mains ruptured.

Groping through the smoke and darkness, some workers plunged to their deaths in the elevator shaft. Others managed to scramble onto the roof of an adjacent boardinghouse.

Horse-drawn fire wagons arrived. Onlookers massed below. Trapped workers jumped from high windows, their clothes aflame. Some crashed to the pavement through firefighters’ feeble nets.

Singed and bandaged survivors rushed to a nearby auxiliary plant to put out a newspaper bearing the headline:

“UNIONIST BOMBS WRECK THE TIMES; MANY SERIOUSLY INJURED.”

The front page carried a preliminary catalog of the carnage:

“CHARLES E. LOVELACE, editorial staff. Jumped from third floor window; injuries perhaps fatal.

CHURCHILL HARVEY-ELDER, burned over body and head; broken right leg; will probably die.”

In the era before DNA, it was impossible to identify all of the dead. In the end, the fatalities would be counted as 21.

Times Publisher Harrison Otis, who had been in Mexico, returned with an editorial addressing the killers. There was no proof it had been a union job, but he was not waiting for confirmation.

“O, you anarchic scum,” he wrote of those responsible. “You leeches upon honest labor, you midnight assassins, you whose hands are dripping with the innocent blood of your victims.” It was the “Crime of the Century,” the newspaper declared, and if Otis had any say in it, the culprits would hang.

The country’s most famous detective happened to be in Los Angeles that day to give a speech. Stout, wily William J. Burns had been dubbed “America’s Sherlock Holmes” by no less an authority than the creator of Sherlock Holmes.

In the era of the heroic private eye, when cops worked in concert with them and often deferred to them, few loomed larger than Burns. He wore a bowler hat and carried a sword cane.

An ingenious self-promoter, former Secret Service agent and future head of the bureau that would become the FBI, Burns detailed his adventures in popular magazines.

The L.A. mayor pleaded for his help. Burns took the case, and later recounted his investigation in a self-mythologizing book, “The Masked War.”

“The war with dynamite was a war of Anarchy against the established form of government of this country,” he wrote. “It was masked under the cause of Labor.” He declared himself a believer in organized labor — but murder was murder.

Of the three bombs McNamara had planted, only the one at The Times worked as intended. A cop had inspected the suitcase left at Otis’ house, heard it whir, and managed to throw it and run before it exploded. The Garland Avenue bomb did not explode at all, and would provide one of the first big clues in the case.

Burns quickly connected it to the attempted dynamiting of an ironworks in Peoria, Ill., the month before. Both devices used the same New Haven Clock Co. Junior Tattoo alarm clock and the same No. 5 Columbia dry cell battery and appeared to have been made by the same hand. What’s more, management at the Peoria site had been threatened by the ironworkers union.

Burns and his operatives zeroed in on the McNamaras. To Burns, J.B. was the “drunken and degenerate weakling tool” of his elder brother, and a conscienceless man who “celebrated his terrible act by scattering money about in the lowest of drinking dives.” Burns believed that J.J., who had a law degree and was secretary-treasurer of the ironworkers union, was the brains of the operation.

The detectives were also shadowing Ortie McManigal, a family man who had been one of the union’s go-to bombers for years, earning $125 per assignment. In “Deadly Times,” a book about the case, author Lew Irwin called McManigal “America’s most prolific terrorist,” with an estimated 150 bombings to his name.

At a hotel in Detroit, the detectives caught McManigal and J.B. McNamara with luggage containing bomb-making equipment. For a week, Burns hid the pair at a cop’s Chicago home to avoid having to “waste time in fighting habeas corpus proceedings,” and went to work extracting a confession from McManigal.

“Preying on his mind all the time was the thought of his wife and children and their fate,” Burns wrote. McManigal had not accompanied J.B. McNamara on the mission to blow up the L.A. targets, but as part of the broader scheme, he was equally guilty under conspiracy laws. Now was his chance to right his wrongs.

1

2

1. Smoke continued to rise from the ruins of the Los Angeles Times building on Oct. 2, 1910, a day after the deadly bombing. 2. A closer look at the mangled north wall of the building, photographed that Oct. 2. (Los Angeles Times)

McManigal came through with a detailed confession, saying he had been dynamiting nonunion shops for years at the direction of J.J. McNamara. Soon, Burns swept into the Indianapolis headquarters of the ironworkers union, where J.J. McNamara was holding court with other high-level union officials. In the union’s vaults were 92 pounds of dynamite and “a great mass of correspondence” from union men around the country requesting bombings.

Later, in his Los Angeles cell, McManigal wept and blamed the McNamaras for ruining his life. He remembered a time when he could look his family in the face after a day of honest work.

“I had no trouble on my mind until they got me to go in with them to dynamite the non-union shops,” he told an investigator, as recounted in “The Masked War.” “After that my life was a hell on earth. Now my wife and innocent children are disgraced.”

Union leaders decided to braid their own fates to the McNamara brothers, who had become a cause célèbre. On Labor Day in the streets of Los Angeles, thousands marched with McNamara buttons. Across the country, collections were taken up for their defense. As a fundraising tool, the American Federation of Labor commissioned a piece of agitprop called “A Martyr to his Cause,” a 15-minute silent film lionizing the elder McNamara and demonizing Burns as a kidnapper.

The union hired defense attorney Clarence Darrow, the famous crusader for the downtrodden. Darrow seemed at first to believe in the brothers’ innocence, arguing that the destruction of The Times had been the result of leaking gas. But he arrived at the painful conclusion that the case was hopeless.

At Darrow’s urging, J.B. McNamara pleaded guilty to the Times murders. He admitted to slipping a suitcase bomb with 16 sticks of dynamite into Ink Alley.

If you have information on old crimes, famous, once-famous or obscure, contact christopher.goffard@latimes.com

“I did not intend to take the life of anyone,” he wrote in a handwritten confession to the court. But the judge called him “a murderer at heart” and sentenced him to life in prison.

The elder brother got off easier. J.J. McNamara pleaded guilty to ordering the bombing of an ironworks building in Los Angeles and was sentenced to 15 years. They were handcuffed together and sent to San Quentin.

In the end, dozens of members of the ironworkers union were convicted federally in dynamite plots. The damage to organized labor was inestimable, seeming to confirm its enemies’ worst suspicions.

“It was a tremendous embarrassment to the unions, and for almost a generation, the union movement was stalled, and it didn’t return until the [Franklin D.] Roosevelt years,” said Irwin, the “Deadly Times” author.

At the time of the bombing, Los Angeles had a population of around 320,000 and was vying with San Francisco, a union town, for dominance in California.

Hollywood is now heavily unionized, but by thwarting the march of organized labor in L.A. for decades, the bombing may have fueled the city’s emergence as a movie factory reliant on cheap labor.

“It could easily be said that the movie industry would not have been here except for the Times bombing,” said Greenstein, the “Bread & Hyacinths” co-author.

The Times itself remained staunchly anti-union for generations after the bombing, but employees voted to form a guild in 2018.

As he grew older, the man who bombed the L.A. Times seemed to feel no pangs of conscience. In a letter to his mother, J.B. McNamara wrote:

“Does a soldier worry about his act if it happens in the line of duty?”

Sources for this report include newspaper archives, “Deadly Times” by Lew Irwin, “The Masked War” by William J. Burns and “America’s Sherlock Holmes” by William R. Hunt.