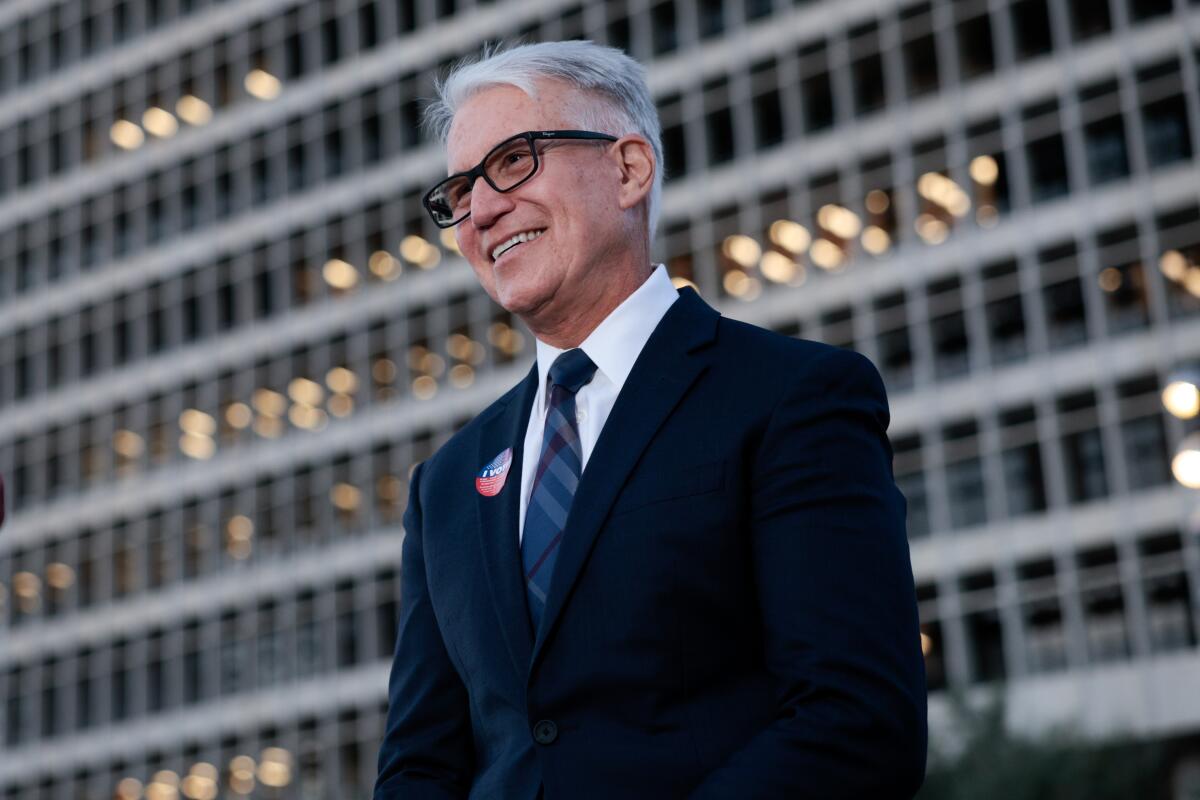

When prosecutor is defendant: L.A. D.A. George Gascón’s legal battles with his own staff

He was elected to be Los Angeles County’s top prosecutor, but George Gascón has spent a considerable amount of his first term as a defendant.

In his first week in office, Gascón sent a political ally to the Compton Courthouse to order a veteran prosecutor to drop criminal charges against three protesters. That mission ended with the county paying out a seven-figure sum to the prosecutor to settle a civil claim.

Earlier this year, Gascón settled a civil rights lawsuit for $5 million from a company at the center of a bungled prosecution that he later had to dismiss amid concerns the charges were based on the word of conspiracy theorists who deny the results of the 2020 presidential election.

Gascón has been named in more than a dozen other civil suits, nearly all of which were filed by his own employees. In total, 20 prosecutors have accused Gascón of workplace retaliation, alleging he pushed them out of leadership positions or into undesirable assignments because they challenged his progressive policies or pointed out portions of his Day 1 directives they consider illegal.

As they try to recall Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. George Gascón, prosecutors still must carry out the enormous workload of the office. With distrust running high, even mundane tasks get more complicated.

It’s no secret Gascón is at odds with most of the office’s line prosecutors, but it’s unlikely any further developments in the pending litigation will affect his reelection battle with Nathan Hochman, as none of the cases are expected to go to trial before November.

But the suits do represent a legal threat that could cost the county millions of dollars, and Gascón has had little luck fending them off so far. A judge recently tossed some claims from prosecutor Jodi Link, but her retaliation allegations will still go before a jury later this year. The only suit to reach a jury so far ended with a March 2023 verdict awarding prosecutor Shawn Randolph $1.5 million. Fourteen suits remain, 13 of which come from inside the office, records show.

Shawn Randolph alleged she was transferred out as head of the juvenile division as payback for speaking out against Dist. Atty. George Gascon’s policies.

The mess of litigation seems to boil down to one central question: When does Gascón’s right to choose his own management and leadership team cross over into retaliation against the people who already held those jobs?

In a brief statement, Gascón denied the allegation that he “has punished employees for criticizing or questioning policies” but declined to comment on any specific lawsuits. His allies have argued that the transfers are well within his discretion to rotate people into different positions in the office. Many of the plaintiffs are also among Gascón’s political enemies: Two of them challenged him in the March primary and several others aided in failed recall campaigns against him or are among his loudest critics.

But several of the plaintiffs argue they tried to work with Gascón and only moved against him after he lashed out. They say the transfers are evidence of the disdain the district attorney has for his own employees, some of whom he referred to as “internal terrorists” during his 2020 campaign.

“I think we just all felt that nobody was listening … it was really the one way we could speak out and talk about what was happening in our office,” said Deputy Dist. Atty. Maria Ramirez, who unsuccessfully challenged Gascón in the March primary and sued him in 2022 over what she saw as a demotion over a policy dispute. The case is ongoing.

Although the sheer number of suits is jarring, the district attorney’s office’s legal costs have remained relatively small during Gascón’s tenure, accounting for roughly 1% of the county’s legal bills from fiscal years 2021 to 2023, according to public reports from the county counsel’s office. The L.A. County sheriff’s and probation departments still draw the lion’s share of the county’s spending on litigation, according to those reports.

But if Gascón were to lose all of the pending suits, those costs could spike. And although the legal costs haven’t added up yet, the wave of claims has led the county to engage in some controversial spending. Earlier this year, the Board of Supervisors approved a motion to rehire Sharon Woo, Gascón’s former second in command, at a salary of $103,000 per year so she could aid in the county’s defense against the complaints.

Woo had retired months earlier, but county officials said they needed her back because of her familiarity with the cases and the surrounding employment matters. Critics quickly decried the move as essentially paying Woo to serve as a witness on Gascón’s behalf.

A judge has granted large portions of a petition filed by the union representing prosecutors that will bar Gascón from enacting some of his reforms.

Many of the suits allege prosecutors were punished for refusing to implement policies they considered “illegal,” including Gascón’s edicts stopping prosecutors from seeking the death penalty or life without parole in murder cases, filing certain serious charges against juveniles and seeking sentencing enhancements under California’s “three strikes” law in cases in which defendants have prior felony convictions.

Only the “three strikes” policy has been deemed illegal by a judge, and the California Supreme Court is set to hear an appeal in that case. Some lawsuits have argued portions of Gascón’s policy on juveniles would force prosecutors to make misrepresentations to the court, which would be unethical, if not illegal.

For example, in her suit, Randolph argued Gascón’s policy barring prosecutors from filing “strike” offenses against juveniles meant she could not charge a teenager with robbery, forcing her to “unlawfully hide the truth from the courts by mischaracterizing many violent offenses.” Some legal experts have said that prosecutors have discretion to file lesser charges and that Gascón’s policies simply invoke that flexibility.

A jury, however, agreed with Randolph.

Leticia Saucedo, a law professor at UC Davis and expert on employment litigation, said plaintiffs seeking “whistleblower” status under California law need to prove they were punished after challenging a policy or behavior they had a “reasonable belief” was illegal. With most of the plaintiffs being decorated attorneys, that may be a steeper hill to climb than for the average person, she said.

“A lawyer’s reasonable cause to believe a policy is illegal is going back and doing the research and figuring out have there been any rulings against [a policy], to figure out whether some argument is a good faith argument,” she said. “You can’t say that there’s whistleblower protection if you simply just disagree with a policy.”

None of the plaintiffs were demoted or suffered a loss in pay or rank, but most complain of being bounced from leadership posts or placed in “dead end” jobs after opposing Gascón.

George Gascón wants the attorney who won federal convictions in the Rodney King beating to oversee police misconduct investigations in L.A. County.

Assistant Dist. Atty. Vicki Adams, the highest-ranking holdover from former Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey’s administration, said she was ousted as Gascón’s chief of staff after questioning the “three strikes” policy as well as the hiring of special prosecutor Lawrence Middleton. Adams, who has more than 30 years of experience, was succeeded in that role by Joseph Iniguez, a young prosecutor who is now Gascón’s second in command, and former public defender Tiffiny Blacknell, who has no prosecutorial experience.

Blacknell and Iniguez, however, both worked on Gascón’s campaign and support his vision of restorative justice. Blacknell also pushed back on criticisms of her experience level. She said she has “21 years of criminal law experience” in her time as a public defender and has held a number of jobs within the district attorney’s office, including leading the victims services and communications bureaus, which now fall under her supervision as chief of staff.

Some believe, as the elected district attorney, Gascón has a right to elevate people who will pursue the policies he ran on.

“Really what we’re seeing is employees who have a different political opinion on how to do the work than their boss. And that’s driving the majority of the lawsuits,” said Cristine Soto DeBerry, Gascón’s chief of staff when he was San Francisco district attorney. She now serves as executive director of the Prosecutors Alliance, a pro-criminal justice reform group. “The prerogative of being the elected D.A. … is they have asked you to set the policy direction for the office, and he has set the direction he promised voters that he would.”

Deputy Dist. Atty. John Lewin is one of the office’s most recognizable prosecutors. He won a conviction against Robert Durst, the Manhattan real estate heir convicted of killing his best friend to cover up the disappearance of his first wife. Lewin was heavily featured in the HBO documentary series “The Jinx.” He alleges Gascón punished him for challenging his policies by moving him out of the Major Crimes unit and assigning him to work as a “calendar deputy” in Inglewood. In the suit, Lewin referred to the new role as “less prestigious” and said he was “devastated” by the transfer.

Lewin has recently faced criticism for some actions related to the Durst trial — a Long Island television station reported last month that he stayed over at the home of Durst’s widow, Debra Lee Charatan, while traveling with his daughter after the trial. His attorneys say Lewin did nothing wrong and Gascón had no knowledge of that trip when he issued the transfer order. The sleepover happened in May 2022, and Lewin was transferred four months later, according to court transcripts and his lawsuit.

“The case was long over. The defendant was dead and could not be further prosecuted and at the time of the trip [Lewin] was not a witness nor a party to any pending litigation,” his attorney, Brian Panish, said in an e-mail.

Robert Durst was convicted Friday in the murder of Susan Berman, bringing to a close a decades-long legal saga that has seen the New York real estate heir accused of killing three people.

The district attorney’s office did not respond to questions about Lewin, who according to his lawyer went out on medical leave due to the “illegal transfer” but is currently trying a case in Inglewood before returning to his leave.

Saucedo, the employment law professor, said claims such as those brought by Adams and Lewin could be successful even though neither plaintiff suffered a pay cut or what could classically be considered a demotion.

“The question becomes whether a transfer in and of itself is retaliation. It can be considered retaliation if there’s things like lost income or wages, or it’s harder to get promoted from that kind of position, or a person loses benefits or even [suffers] emotional distress as a result of the transfer. ... Some transfers may be considered adverse employment actions,” she said.

DeBerry, of the Prosecutors Alliance, said if all the lawsuits are found to have merit, they would make it impossible for district attorneys to run their offices effectively.

“In an agency of 2,000 people, you have to be able to reassign people to get the work done, especially at a management level,” she said, adding that the plaintiffs work for “a large government agency, and that agency has to be able to function on taxpayer dollars to its highest potential. That does not guarantee anyone an assignment of their choice.”

A law enforcement official with direct knowledge of Gascón’s thinking, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss active litigation, said the administration finds it “absurd” that prosecutors think they’re entitled to positions held under the prior administration.

“This concept that we’re stuck with the people that Lacey put in management roles is infuriating,” the person said.

Gascón has no plans to settle any of the suits, according to the official.

A spokesperson for the county counsel’s office declined to comment on the lawsuits against Gascón but said, in general, “the office pursues litigation strategies that are in the public interest and preserve taxpayer resources, including exploring reasonable settlement negotiations if appropriate.”

Greg Smith, a civil attorney representing the vast majority of the plaintiffs, said the lawsuits are not about political retaliation against Gascón but rather about prosecutors trying to hold the line against a leader they believe is breaking the law.

“All of my clients tried to get along with him, all of them did. To a person, not one of them is a Republican, none of them are conservative. I was shocked to find that many of them were very progressive in their thinking,” he said.

“What I found was that these were people who really took their oath seriously and followed the ethical obligations of a prosecutor,” Smith continued. “And I think that’s what Gascón doesn’t understand. You cannot be a prosecutor and skirt the law to meet a specific end.”