California legislators push law change after ruling against family in Nazi looted art case

California legislators plan to introduce a bill Thursday that would bolster efforts by Holocaust survivors, their heirs and other victims to recover artwork and other property stolen from them as a result of political persecution.

Assemblyman Jesse Gabriel (D-Encino), co-chair of the California Legislative Jewish Caucus and lead sponsor of the bill, said the measure was inspired by a recent ruling by the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals that found that current California law required an Impressionist masterpiece looted from a Jewish woman by the Nazis in 1939 to remain with a Madrid museum rather than be returned to the woman’s family in the U.S.

“It immediately made sense to me that this was a unique opportunity to correct a historical injustice and make sure that something like this doesn’t happen again,” Gabriel said. “Respectfully, we think that the 9th Circuit got it wrong, and this law is going to make that crystal clear.”

Gabriel said the bill hopefully will ensure better legal outcomes for other Californian families who have suffered politically motivated thefts — whether past, present or in the future.

“Our hope is that it’s going to help others, other Holocaust victims and other victims of genocide and political persecution,” Gabriel said. “It’s specifically crafted to be applied more broadly.”

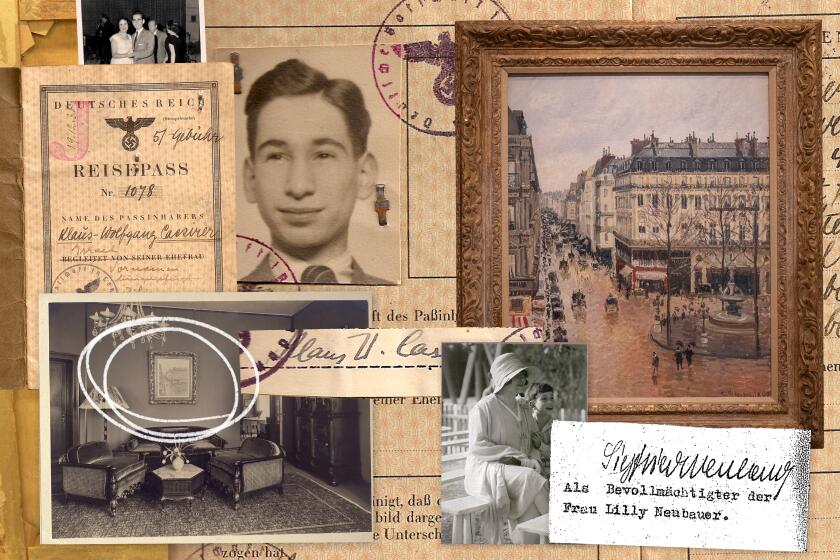

The legislative effort — which Gabriel said already has bipartisan support — is the latest twist in a more than two-decade legal battle over the Camille Pissarro masterpiece “Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon. Effect of Rain.” It is also not the first time the California Legislature has bucked the powerful 9th Circuit on issues related to Nazi-looted art.

David Cassirer, whose great-grandmother Lilly Cassirer Neubauer had the painting stolen from her at the dawn of World War II, is appealing the 9th Circuit ruling against his family and welcomed the legislative effort as a potential leg up in that fight.

“It’s very important that our laws support and enable Holocaust victims and their heirs to be able to recover this artwork that was stolen so long ago,” he said. “I’m grateful.”

Thaddeus Stauber, an attorney for the Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum in Madrid, which obtained the painting as part of a massive collection of masterpieces in 1993 and rejects the family’s claim to it, did not respond to a request for comment.

Neubauer relinquished the painting to a local Munich art dealer acting as a Nazi art appraiser in 1939, in exchange for a visa to flee Germany. It was a decision made under clear duress, as part of a vast Nazi program to steal Jewish wealth, and both parties to the ongoing case have agreed the incident constituted a theft.

A Jewish family’s quest to reclaim a masterpiece painting stolen by the Nazis takes them across oceans and continents, into courts and back through time.

Despite that, however, the Thyssen-Bornemisza, which is owned by the Spanish government, argues it has since obtained proper title to the painting under Spanish law. It says it purchased the painting in good faith, without knowing it was stolen, in 1993, from billionaire Baron Hans Heinrich von Thyssen-Bornemisza.

The baron, one of the world’s most prolific art collectors before his death in 2002, was the scion of a German industrialist family that made a fortune in steel — and helped finance Adolf Hitler’s rise to power along the way.

Neubauer’s family believed the painting was missing — perhaps lost for good in the war — until Neubauer’s grandson Claude Cassirer, who escaped the Holocaust before moving to Cleveland and then retiring in San Diego, discovered around 2000 that it was in the Thyssen-Bornemisza museum.

He asked for the museum to voluntarily return the painting, then sued in 2005 when it refused to do so. David Cassirer, his son, took over as lead plaintiff in the family’s case after his father’s death in 2010.

The case has bounced around U.S. courts ever since, and has repeatedly caught the attention of the 9th Circuit. Around the same time as Cassirer’s death, the appellate court tossed a California rule expanding the window under which looting victims or their heirs could file claims for Nazi-looted artwork, saying it infringed federal authority in such matters.

The state Legislature responded by passing a measure making the window for all sorts of stolen property — not just in international cases with a federal nexus — six years from the time a victim gains “actual knowledge” of the lost property’s whereabouts, which was a window large enough to justify the Cassirer family’s claim. Congress later established a similar window for looted art claims under federal law.

Still, the battle over the Pissarro — which is estimated to be worth tens of millions of dollars — raged on.

In 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court handed the Cassirer family another win when it ruled that California law — not Spanish law — should be used to determine the legitimacy of the family’s claim to the painting. However, in January, the 9th Circuit once again ruled against the family.

A three-judge panel found that California law required it to consider the interests of Spain and of California in enforcing their respective and contradictory laws around stolen property, and to apply the law of the government whose interests would be “more impaired” were its law ignored.

Under that analysis, it had to apply Spain’s law, it found, and therefore the painting had to remain with the museum. One of the judge’s wrote that she agreed with the analysis as a matter of law, but it went against her “moral compass.”

It also went against “California values,” Gabriel said, which is why he decided to introduce the new measure.

“The purpose of the bill is to ensure an outcome based on morality and justice, and not legal technicalities,” he said.

If the new bill passes, it would make clear that, in scenarios involving property looted or stolen by the Nazis or as a result of political persecution, California law dictates that the property be returned, Gabriel said.

The law would apply in any legal case considering such issues in which the ultimate decision is not yet final, up to and including those on appeal before the Supreme Court.

If passed and signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom, the bill probably would take effect Jan. 1, Gabriel said. It also could be expedited, but that hasn’t been considered yet.

The timeline for the Cassirer case is unclear. It currently remains before the 9th Circuit, where Cassirer has asked for the January decision to be reconsidered by a larger, 11-judge en banc panel. After a decision is made there, the parties could potentially appeal to the Supreme Court, as well.

Sam Dubbin, a longtime attorney for the Cassirer family, praised Gabriel’s effort to update California’s law.

“The clarity of Assemblyman Gabriel’s legislation is necessary to change the current dynamic in which governments, museums, and collectors are incentivized to resist restitution and employ tactics and arguments that trivialize the Holocaust,” Dubbin said. “It is essential for truth, history, and justice in the Cassirer case, and for future cases as well.”

Gabriel said he already has co-sponsors from both ends of the political spectrum — including assemblymembers Isaac Bryan (D-Los Angeles) and Vince Fong (R-Bakersfield) — and is optimistic that the bill will have widespread support.

Also backing the measure are Assemblymember Rebecca Bauer-Kahan (D-Orinda), who is the granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, and Lt. Gov. Eleni Kounalakis, also a Democrat, who cited her time as U.S. ambassador to Hungary — where hundreds of thousands of Jews were killed — as strongly informing her support.

“The decades-long effort to return confiscated property to Jewish families is morally courageous,” Kounalakis said in a statement to The Times.

Gabriel said it was “appalling” to him that Spain’s government won’t voluntarily return the painting to Cassirer.

“This isn’t about money,” he said. “It’s about morality and justice.”