Beverly Hills middle school rocked by AI-generated nude images of students

The new face of bullying in schools is real. It’s the body below the face that’s fake.

Last week, officials and parents at Beverly Vista Middle School in Beverly Hills were shocked by reports that fake images were circulating online that put real students’ faces on artificially generated nude bodies. According to the Beverly Hills Unified School District, the images were created and shared by other students at Beverly Vista, the district’s sole school for sixth to eighth grades. About 750 students are enrolled there, according to the latest count.

The district, which is investigating, joined a growing number of educational institutions around the world dealing with fake pictures, video and audio. In Westfield, N.J, Seattle, Winnipeg, Almendralejo, Spain, and Rio de Janeiro, people using “deepfake” technology have seamlessly wed legitimate images of female students to artificial or fraudulent ones of nude bodies. And in Texas, someone allegedly did the same to a female teacher, grafting her head onto a woman in a pornographic video.

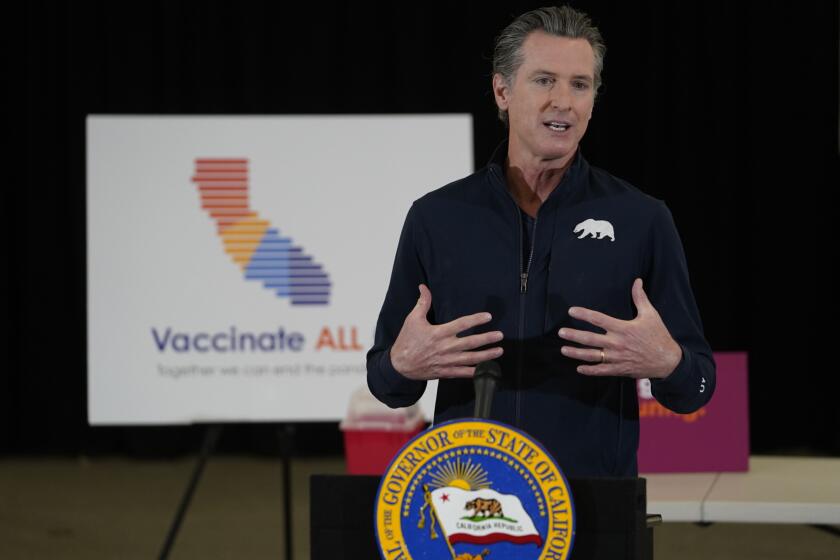

Beverly Hills Unified officials said they were prepared to impose the most severe disciplinary actions allowed by state law. “Any student found to be creating, disseminating, or in possession of AI-generated images of this nature will face disciplinary actions, including, but not limited to, a recommendation for expulsion,” they said in a statement mailed to parents last week.

Deterrence may be the only tool at their disposal, however.

The conservative Supreme Court cast doubt on whether Texas and Florida, the two largest Republican states, can regulate what appears on social media sites.

Dozens of apps are available online to “undress” someone in a photo, simulating what a person would look like if they’d been nude when the shot was taken. The apps use AI-powered image inpainting technology to remove the pixels that represent clothing, replacing them with an image that approximates that person’s nude body, said Rijul Gupta, founder and chief executive of Deep Media in San Francisco.

Other tools allow you to “face swap” a targeted person’s face onto another person’s nude body, said Gupta, whose company specializes in detecting AI-generated content.

Versions of these programs have been available for years, but the earlier ones were expensive, harder to use and less realistic. Today, AI tools can clone lifelike images and quickly create deepfakes; even using a smartphone, it can be accomplished in a matter of seconds.

“The ability to manipulate [images] has been democratized,” said Jason Crawforth, founder and chief executive of Swear, whose technology authenticates video and audio recordings.

“You used to need 100 people to create something fake. Today you need one, and soon that person will be able to create 100” in the same amount of time, he said. “We’ve gone from the information age to the disinformation age.”

AI tools “have escaped Pandora’s box,” said Seth Ruden of BioCatch, a company that specializes in detecting fraud through behavioral biometrics. “We’re starting to see the scale of the potential damage that could be created here.”

The Federal Communications Commission is outlawing robocalls that contain voices generated by artificial intelligence.

If kids can access these tools, “it’s not just a problem with deepfake imagery,” Ruden said. The potential risks extend to the creation of images of victims “doing something very illicit and using that as a way to extort them out of money or blackmail them to do a specific action,” he said.

Reflecting the wide availability of cheap and easy-to-use deepfake tools, the amount of nonconsensual deepfake porn has exploded. According to Wired, an independent researcher’s study found that 113,000 deepfake porn videos were uploaded to the 35 most popular sites for such content in the first nine months of 2023. At that pace, the researcher found, more would be produced by the end of the year than in every previous year combined.

At Beverly Vista, the school’s principal, Kelly Skon, met with almost all of the students in the three grades Monday as part of her regularly scheduled “administrative chats” to discuss a number of issues raised by the incident, she said in a note to parents.

Among other things, Skon said she asked students to “reflect on how you use social media and don’t be afraid to leave any situation that does not align with your values,” and to “make sure your social media accounts are private and you do not have people you do not know following your accounts.”

Another point she made to students, Skon said in her note, was that “there are Bulldog students who are hurting from this event and that is to be expected given what has happened. We are also seeing courage and resilience from these students in trying to get normalcy back in their lives from this outrageous act.”

What can be done to protect against deepfake nudes?

Federal and state officials have taken some steps to combat the fraudulent use of AI. According to the Associated Press, six states have outlawed nonconsensual deepfake porn. In California and a handful of other states that don’t have criminal laws specifically against deepfake porn, victims of this form of abuse can sue for damages.

The tech industry is also trying to come up with ways to combat the malicious and fraudulent use of AI. DeepMedia has joined several of the world’s largest AI and media companies in the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity, which has developed standards for marking images and sounds to identify when they’ve been digitally manipulated.

Swear is taking a different approach to the same problem, using blockchains to hold immutable records of files in their original condition. Comparing the current version of the file against its record on the blockchain will show whether and how, exactly, a file has been altered, Crawforth said.

Those standards could help identify and potentially block deepfake media files online. With the right combination of approaches, Gupta said, the vast majority of deepfakes could be filtered out of a school or company network.

One of the challenges, though, is that several AI companies have released open-source versions of their apps, enabling developers to create customized versions of generative AI programs. That’s how the undress AI apps, for example, came into being, Gupta said. And these developers can ignore the standards the industry develops, just as they can try to remove or circumvent the markers that would identify their content as artificially generated.

Meanwhile, security experts warn that the images and videos that people upload daily to social networks are providing a rich source of material that bullies, scammers and other bad actors can harvest. And they don’t need much to create a persuasive fake, Crawforth said; he’s seen a demonstration of Microsoft technology that can make a persuasive clone of someone’s voice from only three seconds of their audio online.

The attack has left some pharmacies unable to process prescriptions. CVS and Walgreens report limited disruptions.

“There’s no such thing as content that cannot be copied and manipulated,” he said.

The risk of being victimized probably won’t deter many teens, if any, from sharing photos and videos digitally. So the best form of protection for those who want to document their lives online may be “poison pill” technology that changes the metadata of the files they upload to social media, hiding them from online searches for photos or recordings.

“Poison pilling is a great idea. That’s something we’re doing research on as well,” Gupta said. But to be effective, social media platforms, smartphone photo apps and other common tools for sharing content would have to add the poison pills automatically, he said, because you can’t count on people to do it systematically themselves.

![Guitar heatmap AI image. I, _Sandra Glading_, am the copyright owner of the images/video/content that I am providing to you, Los Angeles Times Communications LLC, or I have permission from the copyright owner, _[not copyrighted - it's an AI-generated image]_, of the images/video/content to provide them to you, for publication in distribution platforms and channels affiliated with you. I grant you permission to use any and all images/video/content of __the musician heatmap___ for _Jon Healey_'s article/video/content on __the Yahoo News / McAfee partnership_. Please provide photo credit to __"courtesy of McAfee"___.](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/f4350ab/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1600x1070+0+65/resize/320x214!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F60%2Fef%2F08cda72f447d9f64b22a287fa49c%2Fla-me-guitar-heatmap-ai-image.jpg)